🌌 "My God, it's full of stars!"

The James Webb Space Telescope is a fantastic space megaproject. We need more of them.

The James Webb Space Telescope is a spectacular national achievement. There’s now a $10 billion, 14,000-pound, orbiting infrared observatory with an unfolded, 6.5 meter-wide mirror (three times as big as the Hubble’s with seven times the light-gathering power) parked a million miles from Earth. But the numbers fail to tell as vivid a story as do the initial JWST images. Such as this one:

And the JWST is already generating great science. Check out this intriguing finding from the Canadian Space Agency:

I think, technically, the JWST counts as a “megaproject” because of its cost — if not its otherworldly ambition — although the Earth-based ones typically have some purported economic purpose, such as infrastructure creating a new transportation link or energy generation capacity. Think Panama Canal, Hoover Dam, or the Channel Tunnel. But there are also those who consider some sports facilities to be megaprojects, such as the multibillion-dollar, 70,000-seat SoFi Stadium, home of the NFL’s Los Angeles Chargers and Los Angeles Rams.

Certainly Project Apollo counts as a megaproject. The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management defines them as “large-scale, complex ventures that typically cost $1 billion or more, take many years to develop and build, involve multiple public and private stakeholders, are transformational, and impact millions of people.” Apollo cost some $250 billion, adjusted for inflation, involved nearly a half million workers and a variety of private contractors (Grumman Aircraft, North American Rockwell, and Boeing, among others), and provided a proof of concept that while humanity was born here, it doesn’t need to stay here. (Of course, I wish it had been even more transformational by leading to a permanent lunar colony, vibrant orbital space economy, and human presence on Mars.) Also, Tang. We mustn’t forget Tang.

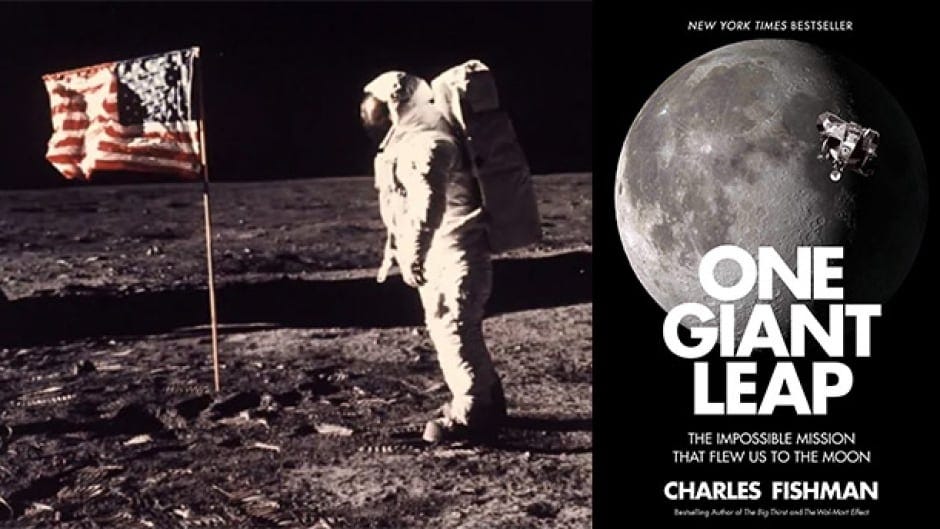

But there’s even more to it than that. In One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon, one of my favorite books about Apollo, journalist Charles Fishman makes the underappreciated point that the Moon program played a critical role in the emerging Information Technology Revolution. NASA purchased most of the microchips produced in the 1960s. This buying power helped put Moore’s Law in motion. With Washington constantly pushing companies to make the chips cheaper, smaller, and more powerful, Silicon Valley continually improved its product and manufacturing process.

Just as important as its impact on the emerging IT Revolution, Fishman argues, Apollo launched a cultural acceptance and embrace of technology that helped make America a gadget-obsessed nation of first adopters. World War II taught Americans about the terrible destructive power of radical new technology. And by the 1960s, concern about nuclear war and nuclear testing was merging with broader environmental worries in a way that eventually contributed to an eco-pessimist, Down Wing cultural turn. It’s not hard to imagine the rise of an anti-computer attitude, whether as something both enabling job loss and the systems that launch nuclear weapons. Just consider how much concern there is today about supersmart “unaligned” AI that might not have humanity’s best interests at heart.

But Apollo provided an Up Wing counterargument, a narrative that still survives. It presented the computer as something that enabled mankind to launch itself into perhaps its greatest adventure, not just calculate ICBM trajectories. It created science heroes in the astronauts, but also heroes of the more everyday sort in the technicians back on Earth. Rows and rows of (almost entirely) men in white shirts and short haircuts diligently going about their work to beat the Soviets to the Moon and boost humanity to the stars.

“[Apollo] helped give Americans a sense of excitement and anticipation about the Digital Age, a sense of excitement that had been completely missing when the 1960s began,” Charles Fishman writes in One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon. “That excitement is still with us. Today, when you first unwrap a new iPhone, when you first boot up a new and newly powerful laptop, that little frisson of excitement you feel is a small echo of the thrill of spaceflight itself.”

While megaprojects may well have huge economic and scientific benefits, they can also create a more aspirational and adventurous Up Wing culture, both in America and globally.

I think the JWST will help do that. Here are a few other space-related ones:

Moon mega-telescope. Isn’t the JWST good enough? Well, here’s the thing: A lunar observatory could have a really big telescope, as on Earth, but without the atmospheric and radio interference of terrestrial telescopes. A proposal from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts Program would suspend a wire mesh dish over a far-side lunar crater.

Mars base. The lunar telescope presupposes a lunar base, so I’m taking the next step here. Elon Musk has estimated that establishing a colony would cost between $100 billion and $10 trillion. The latter number may sound impossible. Then again, the cost of the Covid-19 pandemic has nearly doubled that.

Asteroid capture. The Trump administration's 2018 budget canceled NASA’s Asteroid Redirect Mission, which planned to bring a small asteroid into an orbit around Earth for study and mining. Reviving the project would be a helpful precursor to more ambitious efforts. "While the psychological barrier to mining asteroids is high, the actual financial and technological barriers are far lower,” concluded a 2017 Goldman Sachs analysis.

Alpha Centauri or bust. The Breakthrough Starshot initiative is a private R&D program trying to build tiny, proof-of-concept spacecraft — they would use laser-pushed lightsails to reach 20 percent of the speed of light — for a 20-year journey to Alpha Centauri. It’s next solar system over and home of possible Earth-like planets. A full-scale mission, funded by government, might cost the same as the JWST.

Of course, there are big things we can do on Earth, too — assuming we can get the regulatory piece correct — everything from affordable high-speed rail to hyperloops to refilling the Great Salt Lake. If you have any other ideas, please pass them along!

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples of those interviewees:

Economist Tyler Cowen on innovation, China, talent, and Elon Musk

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on the origins of economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

AI expert Avi Goldfarb on machine learning as a general purpose technology

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy