📉 What 'Shrek' has to do with Moore's Law and the US growth downshift

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Michael Strain on the state of the US economy

In This Issue

The Essay: Shrek, Moore's Law, and the US growth downshift

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Michael Strain on the state of the US economy

Micro Reads: progress studies, thorium nuclear reactors, finding bad genes with AI, and more …

Quote of the Issue

“I am thinking about something much more important than bombs. I am thinking about computers.” - John von Neumann

The Essay

Shrek, Moore's Law, and the US growth downshift

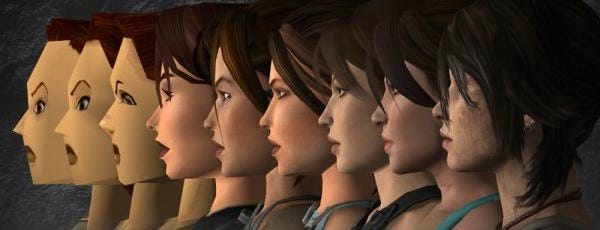

The Lara Croft: Tomb Raider video-game franchise is often employed as visual shorthand to illustrate big improvements in computer power and 3D graphics over the past couple of decades. The image below shows the progression of the character from 1996 through 2014:

Yet progress, such as with digital animation, doesn’t just happen through some inexorable technological momentum. Sticking with animation, there’s the story of Shrek’s Law, a riff on Moore’s Law, the multi-decade observation — coined by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore — that the amount of computing power available at a given price doubles every 18 months. (That works out to a 500,000-fold increase in the number of transistors on modern computer chips.) Some economists credit Moore’s Law with a third of US productivity growth since 1974, or even more.

Seemingly automatic improvements in operating speed, or “clock speed,” helped enable the ever-more realistic depiction of Shrek, the curmudgeonly green ogre from the successful, four-film DreamWorks franchise in the 2000s (2001, 2004, 2007, 2010). Over that period, all aspects of the Shrek-verse — cloth, fur, water, how illumination played off various surfaces — progressively improved. It wasn’t until the third film, for instance, that Shrek could make his horn-shaped ears vibrate when trumpeting them, according to a 2010 Animation World Network story.

But in 2004, Shrek’s Law hit a roadblock when Intel, the world’s largest chipmaker, announced it was canceling the next version of its flagship Pentium 4 chip and shifting away from boosting performance through faster clock speed. Instead, the company would focus on producing “multicore” computer chips — chips with at least two processors on a single chip. And to take full advantage of multiple processors, a software program must be able to split up work among them, or be parallelized. This shift eventually forced a big change by the Shrek animators, as explained by Neil Thompson, an MIT innovation scholar, in the 2017 paper “The Economic Impact of Moore’s Law: Evidence from when it faltered”:

By 2008, after several years without processor speed-ups providing performance improvements for them, Dreamworks made the expensive decision to re-write large parts of their animation code to parallelize it. This allowed them to split up the work that the software was doing amongst the multiple processors on their multicore chips, which their previous unparallelized code had been largely unable to do. This was a success, providing a 70% overall improvement, with particular gains in areas like fluid modelling that lent themselves to parallelization.

There are at least three conclusions that I draw from the story of Shrek’s Law:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.