😑 Is this really America's age of 'anti-ambition' and decadence?

Also: 5 Quick Questions for… physicist and 'The Star Builders' author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

In This Issue

The Essay: Is this really America’s age of “anti-ambition” and decadence?

5QQ: Five Quick Questions for… physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Micro Reads: nuclear regulation, slavery economics, selling the Moon

Nano Reads

Quote of the Issue

“Of course, civilization requires a modicum of material prosperity — enough to provide a little leisure. But, far more, it requires confidence — confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers.” - Kenneth Clark in “Civilization”

💥 Important Update for My Wonderful Faster, Please!Readers and Subscribers

I currently intend to start offering a paid subscription option to Faster, Please! as of March 3 — the very next issue! (I had intended to do it this issue, but I glitched it.) Accessing my twice-weekly essays and Q&A interviews with top thinkers (along with some surprises) would be included in that paid subscription, but not the freebie version. I have been writing this newsletter over the past year at night and on weekends. I hope you find it valuable.

My friends: I still believe we’re at the start of an amazing period of American (and world) history — the beginning of a Great Acceleration in human progress. It’s the purpose of Faster, Please! both to document these steps/leaps forward and recommend the best ideas to make sure they happen, ASAP. You know, faster, please! I look forward to taking that journey — via economics, tech, public policy, business, history, culture, and a smidgen of politics — over the next months and years with all of you. Let’s make a better world for everyone, together. Melior mundus

The Essay

😑 Is this really America’s age of “anti-ambition” and decadence?

We live in the “Age of Anti-Ambition,” at least according to a recent piece by Noreen Malone in The New York Times Magazine. She describes an exhausted nation of workers that hate their jobs or even the notion of having a job. Well, at least the sliver of America she’s familiar with, writing that “almost no one I know likes work very much at the moment.”

But maybe Malone simply finds herself with an anomalously unambitious group of friends. (Perhaps another manifestation of Pauline Kael Syndrome.) A few observations:

More people are being hired each month than in any month prior to the pandemic. The prime-age employment-population ratio (the percentage of the population that is currently working) is rapidly rebounding from the pandemic shock.

A YouGov poll from last summer finding only one in five working Americans feels that their job is “not making a meaningful contribution to the world.”

Similarly, a March 2021 Conference Board survey poll found an increase in job satisfaction from 56.3 percent in 2019 to 56.9 percent in 2020.

Finally, we’re seeing a boom in business start-ups, hardly a sign of zero hustle. The scoop from John Dearie of the Center for American Entrepreneurship: “The 2020–2021 surge in monthly new business applications has continued into 2022, although at slightly lower levels. Overall, nearly 5.4 million new business applications were filed in 2021, up more than 50 percent from 2019 levels.”

The decadence diagnosis

Setting aside its specific factual foundation, Malone’s argument does sync with a broader indictment of modern America, one popularly made by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat in his 2019 book The Decadent Society. Douthat depicts an America that, like the layabout scion of old money, has given up its agency in shaping and preparing for the future.

Part of this decadence diagnosis concerns a “societal crisis of confidence and ebb of optimism.” Douthat also quotes cultural critic Jacques Barzun: “When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent.” So a sense of resignation is part of decadence, too, I guess. (Of course, this accusation of American decadence isn’t limited to American journalists and intellectuals. The madman Vladimir Putin, like many authoritarians, touts his rotten regime as an antidote to or bulwark against the supposed decadence of the materialist, exhausted, liberal democratic West.)

America’s long-term economic stagnation is one aspect of its utter exhaustion, according to Douthat. Emphasizing the “economic element” of decadence, he adds, “limits the scope of decadence to societies that are actually stagnating in a measurable way and frees us from the habit of just associating decadence with anything we dislike in rich societies or with any age (Gilded, Jazz) of luxury, corruption, and excess.”

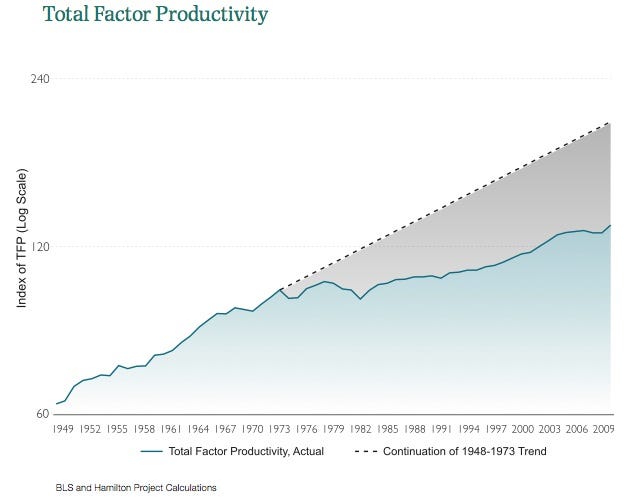

There’s definitely a measurable economic basis for the stagnation claim. Americans in the early 1970s experienced a surprise deceleration in technological progress and economic growth starting in 1973. Instead of real GDP growing at 4 or 5 percent annually and indefinitely as many 1960s optimists predicted, the economy has been growing at less than 3 percent annually for the past half century overall — and far slower since the Global Financial Crisis. The main reason growth is substantially below those forecasts of a half-century ago is that productivity growth has been much slower than expected. The part of productivity growth that represents innovation has utterly collapsed, declining from an average of 2.2 percent from 1948 through 1973 to just 0.5 percent over the subsequent three decades, rising during the 1990s and early 2000s, and then trailing off again.

Great Depression meet the Great Downshift

My long-standing baseline explanation for this Long Stagnation is this, basically:

As posited by Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon, the 1960s were the last decade of a “special century” of advancement built on the great inventions of the late Industrial Revolution, such as the combustion engine, electrification, and telecommunications. “We’ve had plenty of inventions since 1970 but it’s been focused on the narrow sphere of entertainment, information, and communications technology,” Gordon told me in a 2016 conversation. “Those innovations are everything that we talk about today, but in perspective they’re just a small slice of what human beings care about. If we looked at food, clothing, shelter, transportation, entertainment, motion pictures, we have achieved relatively slow progress since 1970.”

It's been getting harder to discover the big advances and breakthroughs that drive technological progress and economic growth, as explained in the paper "Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?" by economists Nicholas Bloom, Charles Jones, John Van Reenen, and Michael Webb. The low-hanging fruit has been picked. For example: They find that the number of researchers needed to achieve the famous Moore’s Law doubling of computer chip density is more than 18 times larger than the number required in the early 1970s. Their conclusion: “Just to sustain constant growth in GDP per person, the United States must double the amount of research effort every 13 years to offset the increased difficulty of finding new ideas.”

At the same time that fast progress was getting more difficult to achieve in the 1970s, the US started neglecting many key things that were critical to the continued acceleration of scientific discovery and technological innovation: Less science investment. Less infrastructure investment. And it started doing too many things, especially environmental and labor market regulation, that made it harder to exploit the discoveries and innovations we did make and generate.

To the above items, I would now add the “zero-risk” society thesis of Peter Cauwels and Didier Sornette at ETH Zurich, as posited in their 2020 paper

“Are ‘Flows of Ideas and ‘Research Productivity in secular decline?” (Spoiler: Their answer is “Yes.”) Too much focus on incremental exploitation (innovation) in disregard of drastic creativity (invention) and exploration (discovery). And they attribute this imbalance to the fact that “affluent society has become extremely risk averse.” One explanation might simply be that as we have become more affluent, the marginal utility of increased wealth has diminished, thus prompting less aspirational values. For their part, Cauwels and Sornette identify a cluster of deeper causes: societal aging, inequality (daily life is already plenty risky for the left behind), too much confidence that technology will magically save us from any harm, and social media amplifying all our fears and worst impulses.

But I do think there’s a cultural component to the downshift. Starting in the late 1950s, the emerging environmental movement started telling Americans a story about the costs of progress, how in too many cases they outweighed the benefits. These worries then turned into a broader conviction that the future needed to be a place of scarcity and stagnation in order to preserve the planet. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 was followed by Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb in 1968, which was followed by the Limits to Growth report in 1972. The techno-optimist futurists of the 1960s became harbingers of apocalypse in the 1970s. Moreover, this catastrophism seeped into popular culture — from Planet of the Apes and Soylent Green back then to The Day After Tomorrow and Don’t Look Up today.

The result: A sort of self-reinforcing doom loop or “idea trap”: bad ideas and bad stories lead to bad policy, bad policy leads to bad growth, and bad growth cements bad ideas and encourages more bad stories.

Does the above qualify as “decadence?” It does in the sense of rampant pessimism and a deficit of confidence, for sure. But less so, perhaps, in the strict Barzunian sense. I think the eco-pessimists, both then and now, are telling the wrong story, but they have an image of the future that they are actively trying to create. Not lacking in ambition, they are pushing for a radical transformation of the planet’s dominant socioeconomic system. Plus they think they have the facts on their side.

More importantly, I think, the decadence argument partially ignores that there have been considerable efforts to break out of the Long Stagnation. When the downshift happened — and remember, this occurred across advanced economies — American experts didn’t realize they and the rest of the West had probably squeezed most of the gains out of the Great Inventions and really needed to find some great new ones. They didn’t realize much of the low-hanging fruit of discovery and invention had been picked so now would be a bad time to reduce research spending. They didn’t realize a flood of new regulations might be good for the environment in the short term but bad for generating rapid long-term technological and economic progress, both of which were more precarious than they realized.

Moreover, it’s easy to see how policymakers were tempted to write off the slowdown as a temporary hiccup related to easily identifiable economic events and policies. All they had to do was pick up a newspaper or turn on the evening news. One obvious culprit for the slowdown was the Arab oil embargo that began in October 1973 — the same year the postwar productivity boom ended — and lasted about five months. But over the course of the decade, economists began to realize that the productivity slowdown was no ephemeral event. The 1977 Economic Report of the President described the falloff in productivity growth as “striking,” while also admitting the causes “are not fully understood at this time.”

Washington tries to restart the American growth machine

Yet even without a full understanding of the productivity puzzle, Washington has long been aware of the productivity problem. President after president, decade after decade, has highlighted anemic or declining productivity growth as a pressing national concern. For example: Bill Clinton in his first nationwide address pointed out how “two decades of low productivity growth” meant America risked “condemning our children and our children's children to a lesser life than we enjoy.” He continued:

Once Americans looked forward to doubling their living standards every 25 years. At present productivity rates, it will take a hundred years to double living standards, until our grandchildren's grandchildren are born. I say that is too long to wait.

Looking back across six presidencies, some common themes emerge. America’s leaders generally recognized the importance of scientific discovery, technological innovation, and economic growth. And they showed concern about the productivity slowdown, offering policies to reverse it once they recognized its longer-term nature. And when economic growth was booming, they spoke of supporting that growth.

But those well-intentioned responses were hindered by the surprise start of the slowdown, ignorance of its causes, and an underestimation of its severity. Their responses simply failed to meet the scope of the challenge, whether they involved cutting taxes, increasing spending on new research programs from time to time, or announcing big ideas — like Jimmy Carter and his clean energy plan or George W. Bush and his initiatives for hydrogen fuel and nanotechnology.

In the end, all those policies proved ineffective or insufficient to accelerate the next wave of Big Inventions. But you can’t say America hasn’t tried. And it’s important that we learn from our failures and keep trying. Much of what this newsletter is about is highlighting pro-growth ideas that might be effective.

It’s important that we stop the negative self-talk (that NYT piece on “anti-ambition” repeats the misunderstanding that US wages have been stagnant for decades) and tell ourselves a different story about the future — one where scientific research and entrepreneurial risk-taking creates a tomorrow of greater prosperity and opportunity. Cauwels and Sornette: “Why not promote the risk-taker, the explorer, the creative inventor as a new type of social influencer acclaimed like a Hollywood or sports star? Only by such a deep cultural change, by bringing back the frontier spirit and making risk-taking great again will we be able to escape from the illusionary and paralyzing zero-risk society.”

The good news here is that there’s evidence that with a bit of progress, America’s natural confidence is quick to recover. It wasn’t long ago that frequent presidential promises about America’s future in space only reminded us of the failure to build upon Apollo. Yet now that an American entrepreneur — with wealth originally derived from the IT revolution — is finally building upon Apollo’s achievements, that Apollo confidence has quickly returned. Entrepreneurs and scientists are seriously talking about multiple space stations, lunar bases, and Mars colonization. One wonders where further breakthroughs in AI, fusion, and genetic editing might lead to — and how they might energize and inspire us. Perhaps next up are Ages of Aspiration and Daring!

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ Five Quick Questions for … The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on nuclear fusion

Arthur Turrell is Deputy Director at the Data Science Campus of the Office for National Statistics in the UK and the author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet. I did a super-informative podcast with Turrell back in October. But there continues to be so much news on the subject that I thought an update is called for.

1/ There seems to be a lot of fusion-related news of late. Let me highlight just two: Earlier this month, scientists at the Joint European Torus fusion experimental facility located in the UK announced that they had generated “the highest sustained energy pulse ever created by fusing together atoms, more than doubling their own record from experiments performed in 1997,” as Nature described it. In addition, an AI system owned by Google-back Deep Mind has just "learned" how to control a magnetic field in a tomak fusion reactor — and it could help could pave the way for new reactor designs. How significant are these developments?

JET’s breakthrough is significant for two reasons, even though it only produced 0.3 units of energy out for every unit of energy put in. First, it takes fusion a step closer to industrial scale: the power output was equivalent to 4 wind turbines and the energy from reactions, although modest, was a world record for controlled fusion. Second, it ran for five seconds — now, I realise this doesn’t seem very impressive. But five seconds is a long time in nuclear physics and, here comes the key point, the experiment didn’t stop because the hot fuel went unstable and cooled down (a problem that is common but also hard to fix); it stopped because the equipment around the reactor became too hot (a problem that is easy to fix). This experiment demonstrated stable operation at scale and means that the next generation of similar machines is likely to be able to make the leap from five seconds to five minutes, and even to continuous operation.

DeepMind’s recent paper is impressive in that it opens up significant new possibilities, but you may be surprised to learn that the use of neural networks to control fusion reactors goes all the way back to 1994! (You can find further details on this here and here.) In fact, the group at DeepMind aren’t even the first team in Google to apply machine learning to fusion and there is a very healthy machine learning community within fusion, as this review written by some of my former colleagues spells out. JET has even used deep learning to forecast turbulence and instability, to help get closer to continuous operation. So what does the DeepMind work add? It’s a proof of principle of using reinforcement learning to control a reactor: this enables scientists to say what the goal should be (ultimately, energy yield) and to let the machine get on with deciding how to do it rather than scientists having to go through the laborious job of specifying how the goal of stable fuel should be achieved.

2/ What should we be looking for when new fusions advances or breakthroughs are reported?

Right now, the most important goal is demonstrating that reactors can reliably and repeatedly achieve the magic combination of temperature, density, and confinement (called the “triple product”) that we know is needed for sustained fusion reactions to work. Picking this information out can be tricky though, even for experts, so an easier way to gauge progress is to look at the energy gain — how much energy came out of the experiment per unit of energy put in? Although commercial reactors will need to produce more than thirty times as much energy out as went in, the goal for now is to reach as much energy out as put in (i.e. one unit). The leading laser fusion experiment, the National Ignition Facility, and the leading magnetic fusion experiment, JET, have reached 0.7 and 0.67 respectively.

3/ Why is a tokamak reactor that began operating 35 years ago still the best in the world? Or more broadly, why has the progress developing fusion power been so slow? This is a dream of the 1960s.

How fast technological progress goes depends on how much we, as a society, want it. Societal will and investment can speed up technology — just look at the development and deployment of vaccines during coronavirus. Given that achieving fusion is perhaps the greatest technological challenge we’ve ever taken on as a species, funding for fusion to date has not been equal to the task. Progress could have been much faster. However, the example of JET is a bit misleading: it’s really a different machine to the one it was 35 years ago. There have been many upgrades, replacements, and additions in that time, most importantly a complete switch from carbon construction to walls made of tungsten and beryllium (materials that will also be used in the next generation machine, called ITER, which is being constructed in France). JET is also unique in being the only tokamak in the world that runs with fuel that can undergo fusion reactions rather than inert hydrogen, though other magnetic machines are pushing progress in other ways—for example, China’s EAST machine recently demonstrated a 1,000 second run at 70 million degrees using inert fuel.

But I do want to challenge you on whether the progress has been slow. Compared to the investment, the progress has been phenomenal — literally exponential, as the animation I’ve attached shows.

4/ Robert Zubrin has argued that net energy gain fusion is more likely to come from a startup than ITER or NIF. Do you agree? Why or why not?

No, I don’t agree — NIF has demonstrated 70% energy out for energy put in and, because laser fusion scales so dramatically once reactions begin, they are very likely to hit 100% before anyone else. They have a machine running today that is already creating large numbers of fusion reactions. No start-up can say that. In fact, as far as I know, only one start-up so far has experimented with the special types of hydrogen that commercial reactors will need to use. What type of machine or approach will be most successful in making fusion commercially viable is another question though, and one we don’t know the answer to. So I do see the private sector playing an extremely important role in perfecting/scaling the technology and in making it cheap.

5/ What are the key steps remaining to achieve a commercial fusion reactor?

There are five steps, but it’s essential the first one is cracked to unblock the rest:

Demonstrating reliable and repeatable net energy gain at scale, with a yield of at least thirty times energy out for energy in. For magnetic fusion, this means running for time periods of at least hours continuously. For laser fusion, it means running 5 or 10 ’shots’ per second.

Developing a method of ‘breeding’ one of the key ingredients for fusion, tritium (a special type of hydrogen), from lithium by placing lithium close to the fusion reactions.

Mastering the materials science needed to ensure that reactor components can withstand the highest temperatures in the solar system through many years of use.

Turning the energy released by fusion reactions into electricity.

Rolling fusion reactors out on an industrial scale at reasonable cost.

If society can do those, we will have delivered ourselves a clean, CO2-free source of energy that could last for millions and perhaps billions of years.

Micro Reads

⏩ Slavery Was Never an American Economic Engine - Trevon Logan, Bloomberg | Yes, the Ohio State University economist concedes, slavery was profitable practice for slave owners, with annual expected returns of 7 percent to 10 percent year. Also: “[The] market value of enslaved people [was] estimated to have been $4 billion as of 1860 — more than every bank and railroad combined at the time.” But coercion led to productivity that was a third of northern counterparts. And emancipation created a huge productivity shock:

In work with Richard Hornbeck, I have sought to quantify the value of freedom to those who were freed — the wealth created by reallocating 13% of the population from slave labor to using their time as they saw fit. We found that the benefit to the formerly enslaved far exceeded the associated declines in output of cotton and other relevant goods. So instead of destroying wealth, emancipation actually delivered the largest positive productivity shock in U.S. history. Under conservative assumptions about the value of non-working time to enslaved people, we estimate that the productivity gain was roughly 10 percent to 20 percent of gross domestic product.

⚛ Feds walk back plans for nuclear reactors to run 80 years - Kristi E. Swartz and Jeremy Dillon, E&E News | Here’s yet another reason that we need to expand capacity with new builds. Regulators have added considerable uncertainty to the notion that “pushing the age of current reactors” will be a “critical tool” for achieving net-zero emissions goals over the coming decades. And, of course, NEPA makes an appearance right on schedule: “The Nuclear Regulatory Commission told Florida Power & Light that its two Turkey Point nuclear reactors must go through a full environmental review before the agency will allow them to run for an additional 20 years. The NRC agreed with a legal challenge from several environmental and consumer groups, which argued that a full National Environmental Policy Act review is needed for the already aging reactors to run another 20 years.” This could tack on at least another three years to the regulatory review process.

🌙 Space Invaders: Property Rights on the Moon - Rebecca Lowe, Adam Smith Institute | Reasoning through the implications of the classical liberal conception of property rights, as expressed in the writings of John Locke, this report argues that the current treaties governing space are woefully inadequate for the greater commercialization of the Moon that is beginning to emerge today. In space as on Earth, property rights are an efficient and, the author argues, morally-justified economic institution. But the Cold War–era international treaties in use today outlaw the "national appropriation" of property in space. It's worth considering, then, how to structure legal institutions for the promotion of private property in space, for assigning lunar property rights would present economic benefits, provide "incentives for the responsible stewardship of space, as well as opportunities for new scientific discovery, democratised space exploration, and much more."

Nano Reads

▶ The Missing Baby Bust: The Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Contraceptive Use, Pregnancy, and Childbirth among Low-Income Women - Martha J. Bailey, Lea J. Bart, & Vanessa Wanner Lang, NBER |

▶ A new book suggests that the best way to save the planet is through abundance - Derek Thompson, The Atlantic |

▶ The Metaverse Is Coming: We May Already Be in It - Rizwan Virk, SciAm |

▶ Should the U.S. Government Subsidize Domestic Chip Production? - Will Hunt, WSJ |

▶ Francis Fukuyama: Will We Ever Get Beyond The Nation-State? - Francis Fukuyama, Noema |

▶ Drain Putin’s Brains - Robert Zubrin, NRO |