💢 The productivity-pay 'gap': a pernicious economic myth

Also: 5 Quick Questions for . . . Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara

“Once you start thinking about growth, it's hard to think about anything else.” - Nobel laureate economist Robert Lucas.

In This Issue

Essay: The productivity-pay 'gap': a pernicious economic myth

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for . . . Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara

Micro Reads: nuclear fusion, our future in space, China tech, and more …

Nano Reads

Essay

💢 The productivity-pay 'gap': a pernicious economic myth

I get this a lot: Why do you care so much about trying to accelerate productivity and economic growth? Are you some sort of neoliberal, “Make the line go up,” “What’s good for Wall Street is good for America” obsessive sicko? If you were a regular New York Times reader, you would know all about the “productivity and pay gap,” the long-term delinkage between worker output per hour and worker compensation. Productivity and economic growth don’t matter, redistribution does. I thought you worked at a think tank. Maybe you need to think harder, dude!

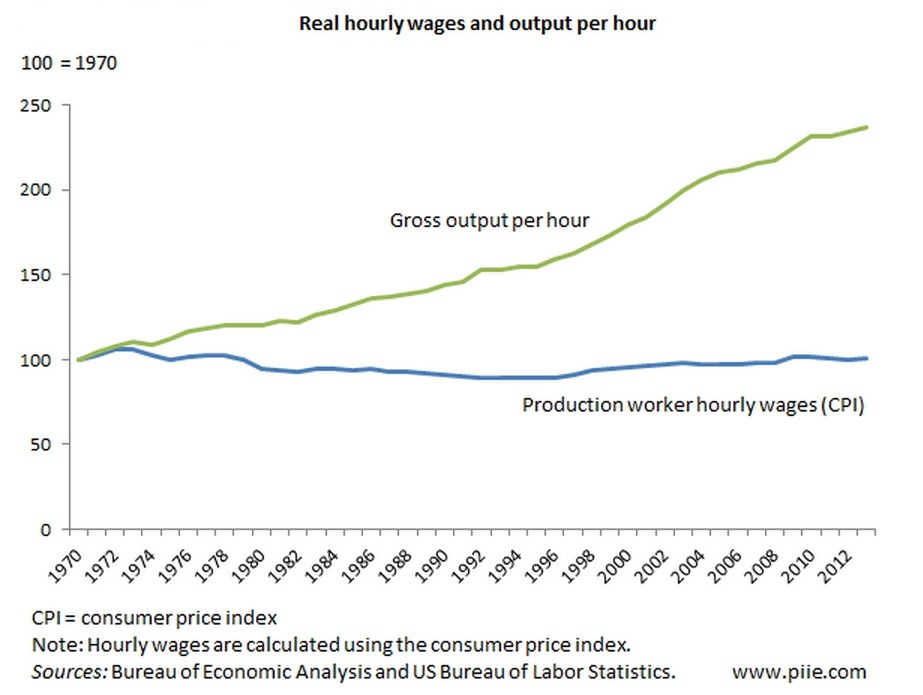

Well, something like that, I guess. Anyway, the popular notion that productivity no longer drives compensation — productivity growth may have been slow since the 1970s, but inflation-adjusted pay has been stagnant — is reflected in various versions of this chart:

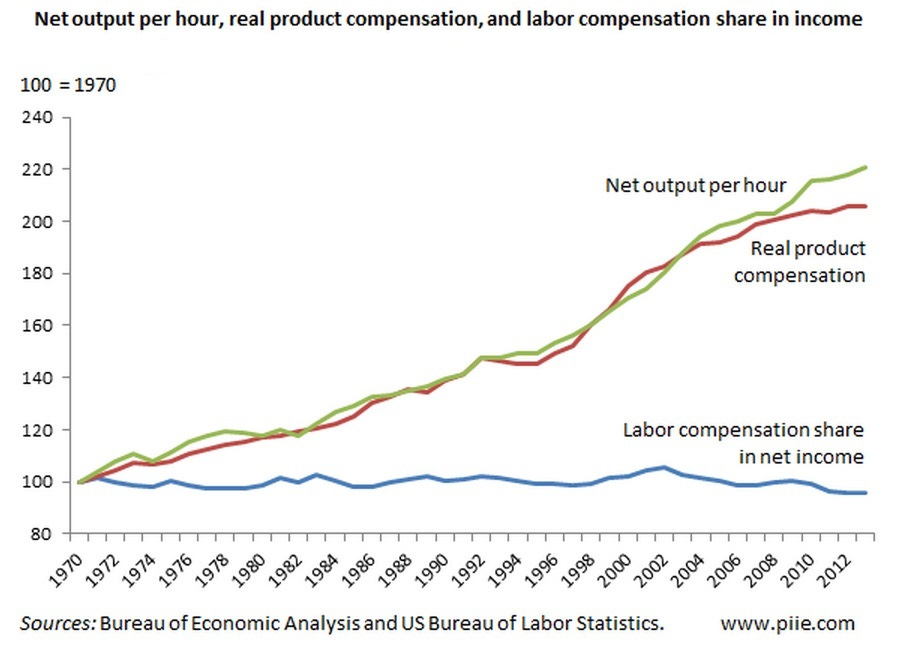

Mind the (productivity-pay) gap! But that chart sends a misleading message. And voracious news consumers who’ve seen it, or something like it, may have been confused by my recent 5QQ interview with AEI economist Michael Strain. He advocated “lighter taxes on business investment” because that would “lead to higher worker productivity,’ which in turn ‘would lead to higher wages for workers.” It’s the sort of policy recommendation that emerges from an understanding of this chart:

Robert Lawrence of the Peterson Institute created both of the above charts a few years back, and he contends the second chart better reflects the tight productivity-compensation relationship. Why the difference between the two charts? Lawrence made several modifications to the first one: (a) adjusted for an overly narrow definition of workers; (b) added in benefits to wages, (c) used an inflation measure that better accounts for what workers actually purchase; and (d) used a more relevant productivity measure.

Stagnant pay?

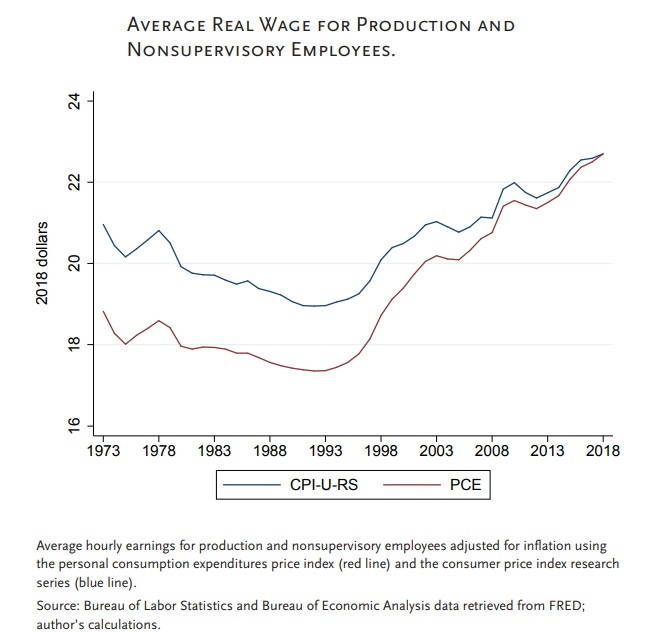

Key to the productivity-pay gap claim is the notion that since the early 1970s, real wages have gone pretty much nowhere. Maybe just a tiny 5 percent gain since the Nixon administration. Sure looks like stagnation, or a pretty close facsimile.

But using that 5 percent number to encapsulate some five decades of American economic history is problematic. Since the 1990 business cycle peak, wages are up 20 percent in real terms. And if you use the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index rather than the Consumer Price Index as the inflation measure — it’s the one preferred by the Federal Reserve and Congressional Budget Office — you find a 32 percent increase in average worker wages and about the same for the bottom fifth of workers. Fun fact: Broader after-tax income measures show middle-class living standards up by 42 percent since 1979 and 70 percent for the bottom fifth. (For more on all of this, I highly recommend Strain’s 2019 book The American Dream Is Not Dead, from which the below chart is taken.)

Productivity growth never stopped mattering for wage growth

In “Productivity and Pay: Is the link broken?” Harvard University’s Anna Stansbury and Lawrence Summers find higher productivity growth is associated with higher average and median compensation growth. They use the median wage and the average wage of production and non-supervisory employees, as well as the average wage of all workers. In order to smooth out the up and downs of the business cycle, they calculate the three-year moving average of the change in inflation-adjusted compensation and labor productivity. Their findings (bold by me):

We find substantial evidence of linkage between productivity and compensation: over 1973-2016, one percentage point higher productivity growth has been associated with 0.7 to 1 percentage points higher median and average compensation growth and with 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points higher production/nonsupervisory compensation growth. … Our results suggest that productivity growth still matters substantially for middle income Americans.

Moreover, boosting productivity growth is at least as good for workers as reducing inequality. Stansbury and Summers note that if inequality had stayed at 1973 levels, the median worker’s pay would have been around 33 percent higher in 2016. But if productivity growth had been as fast over 1973–2016 as it was over 1949–1973 — about twice as high — median and mean compensation would have been around 41 percent higher. (Recall that the supposed “golden age” for American workers in the immediate postwar decades was also a time of rapid productivity growth.) S&S:

These point estimates suggest that that the potential effect of raising productivity growth on the average American’s pay may be as great as the effect of policies to reverse trends in income inequality. Conversely they suggest that a continued productivity slowdown should be a major concern for those hoping for increases in real compensation for middle income workers.

Productivity growth still matters for take-home pay

Likewise, the slowdown in productivity growth also provides a large part of the explanation of slow wage growth in the late 2010s — that, even though unemployment was even lower than what it was in the fast–wage growth era of the 1990s. The problem: Productivity growth has been rising only a quarter as fast as back then.

As economist Jason Furman wrote for Vox in 2019, it’s no mystery as to why wage growth was so fast in the late 1990s, but less so in the years leading up to the pandemic. Furman points out that productivity growth back then rose at a spectacular 3 percent annually versus just 0.7 percent annually more recently. Furman: “That’s part of the explanation for slow wage growth: Based on the productivity numbers alone, one would predict that average wages would be growing about 2.3 percent more slowly than they did in the late 1990s.”

And let me highlight this from Furman (bold by me): “Greater productivity growth holds the potential of being the most powerful source of sustained wage growth across the income spectrum.” (I like that so much, I might start using it instead of the famous Paul Krugman quote, “Productivity isn't everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.”)

Thinking that productivity doesn’t matter or is a mere secondary or tertiary factor is why I use the word “pernicious” in the headline. Misunderstanding the continued value of productivity growing means misunderstanding the foundation of modern prosperity.

To (almost) conclude: Faster productivity growth is superimportant for faster rising living standards. And the sort of scientific discovery, technological invention, and commercial innovation that boosts take-home pay will also accomplish a lot of other pretty important things: increased opportunity, less poverty, healthier lives, a more stable climate, a multi-planetary civilization. I hope that’s one lesson we’ve all drawn from the rapid mRNA vaccine development over the past two years.

Next steps

So what’s the policy advice here? For faster productivity growth, I would point you to the many editions of this newsletter in which I’ve written about deregulation and great science investment, among other things. Moreover, the continued strong connection between pay and productivity argues for making workers more productive, especially those toward the bottom of the income distribution. I’ll give Strain the final word here, from a 2019 analysis:

Policies to increase the skills of, and training available to, workers — for example, reforms to our K-12 education system and the expansion of apprenticeships and other forms of work- based learning — should be enacted. Earnings subsidies should be expanded to draw more people into the workforce. Policies to encourage business investment should also be considered. Labor market regulations that serve as barriers to workers and reduce the quality of matches between workers and jobs should be removed.

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for . . . Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara

Margaret O’Mara is the Howard & Frances Keller Endowed Professor of History at the University of Washington. O’Mara writes and teaches about modern America, the history of the technology industry, American politics, and the connections between the two. O’Mara is also a frequent contributor to the Opinion page of The New York Times. In addition, she is the author of 2019’s The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. (You can check out my 2019 podcast chat with her here.) O’Mara recently wrote a wonderful piece for Wired, “The Secret to Building the Next Silicon Valley,” that prompted this 5QQ.

1/ What’s the biggest or most persistent misconception about the creation of Silicon Valley that hampers efforts to encourage new tech hubs?

The most persistent misperception about Silicon Valley is that government had little to do with its creation. That assumption is changing as people become more aware of the industry’s history, but there still is confusion about how policy worked.

Essentially, during the early Cold War the U.S. threw a huge amount of money in Silicon Valley’s direction and then mostly got out of the way. The money was new, but was spent in the same way the U.S. had subsidized infrastructural and industrial development since the Founding: flowing indirectly to private industry, higher education institutions both public and private, and states and localities. An intensely competitive, entrepreneurial, wealth-creating business culture grew atop a reliable foundation of public financing. The political tradeoff: this indirect and privatized structure hid the true extent of government involvement, even from those who benefitted from it the most.

Would-be tech hubs race to offer the most tax breaks and subsidies that will lure companies to their regions from elsewhere. But tax breaks are not the same as proactive investment (and, as nearly any Californian entrepreneur glumly will inform you, the secret to Silicon Valley is not low taxes). This is not only about investing in next-generation tech. It is also about investments in people and places to sustain dynamic, opportunity-rich communities.

2/ Why should we try to build the next Silicon Valley rather than making our existing tech hubs bigger, more affordable, and more productive?

Tech power and wealth is greater than ever before. It’s also more intensely concentrated in a few places, people, and companies. This isn’t healthy for the state of the nation or for tech. We need to increase the oxygen in the industry so new people can enter and new ideas can grow.

More oxygen can come by making existing tech hubs more affordable and pushing top executive and VC ranks to become more diverse. Regulatory carrots and sticks can allow startups to stay independent longer and curb large companies’ appetites for innovation-through-acquisition. All are possible with enough political will, imagination, and patience. In the meantime, widening tech’s geography can energize the sector by bringing in new people, enterprises, and ideas.

That is what happened in Silicon Valley in the 1950s and early 1960s. Coming into the Cold War, tech wealth and investment capital was tightly concentrated on the East Coast. The engineers who migrated to a semi-rural valley in Northern California for defense-sector jobs in these early days were mostly from humble backgrounds, lacking school or family connections that could have landed them a position at those big corporations back East. Given a chance at a time and place where such pedigree no longer mattered, these Silent-Generation scholarship kids became executives, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists behind generations of stunningly successful companies.

3/ Don’t the unique WWII-related circumstances of the creation of Silicon Valley suggest that while we think we know some of the key ingredients, recreating the exact recipe will be difficult?

Silicon Valley got really lucky. The wartime and early Cold War circumstances that made it a high-tech capital won’t occur again. But in the broadest terms, its success does follow a pattern that appears repeatedly in human history.

New ideas and creative transformations are products of preexisting and distinctive regional characteristics and cultures. When three ingredients are added, these baseline core competencies spark and scale up. First: capital, either in the form of a deep-pocketed patron (say, the Medici of Renaissance Florence) or institution (the U.S. Cold War military). Second: institutions, that allow intellectual exploration and discovery away from immediate market pressures. From the School of Athens and the Tuskegee Institute to modern research universities, these kinds of spaces are critical to fostering new ideas and nurturing talent. Third: quality of place. What this looks like changes over time and space, but at its essence it’s the thing that gives people reason to migrate to a place and a reason to stay there. Given today’s mobile and global tech workforce, being able to attract and retain talented people bestows an enormous regional advantage.

4/ In 2021, US investments in venture capital exceeded $300 billion for the first time. The US has almost as many unicorns as the rest of the world combined. Does that not suggest current public policy is reasonably effective?

Today’s boom reflects many things U.S. policy and politics made possible: a pro-entrepreneurship climate, the best higher education system in the world, a forward-thinking immigration policy. It also reflects another public policy that certainly is effective, although maybe not so desirable over the long term: a zero-interest-rate monetary policy environment that’s led to an enormous amount of investment capital sloshing around the global financial system during the last decade-plus. Much of this money has found an exuberantly lucrative home in the tech sector.

This has upsides. Entrepreneurs more easily obtain financing, more companies start and grow, and tech employment has galloped upward despite the pandemic’s many disruptions. The sky-high stock valuations of public companies are creating employee fortunes that later will fund future generations of startups.

But it’s distorting the market. Not-great companies are getting financed along with promising ones. As deep-pocketed outside investors rush in, due diligence is not always as diligent as it should be. Companies can remain private longer, which allows more time for product development but can perpetuate questionable business models or cover up outright fraud. Non-tech companies present themselves as tech companies, promising returns of a scale and speed they can’t possibly deliver. The implosions of WeWork and Theranos are extreme recent examples of what these conditions can enable.

5/ With better policy, what does success look like at the end of the day?

Success looks like more people being given a chance. The escalator of upward mobility that helped Silicon Valley’s first generation isn’t working like it once was. Elite universities are punishingly selective, tech hubs are hugely expensive, and the startup hustle often requires outside support from family or friends to get through the lean first months. Despite plenty of talk about the need for more diverse perspectives, tech leadership remains overwhelmingly white and male.

The American immigration system isn’t as welcoming as it once was, either. Industry leaders rightly advocate for letting additional high-skilled workers come here, but that’s only one piece of the puzzle. The U.S. needs to invest in human potential, too.

Here’s one example. In 1959, a 20-year-old refugee from Communist-controlled Hungary arrived in New York. He spoke broken English, wore Coke-bottle glasses, and hadn’t finished college. The immigration official who processed his paperwork likely wasn’t all that impressed.

Within a few years, the man who by then went by the name Andy Grove had finished his degree, tuition-free, at New York’s City College. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley. He became the third employee at a newly formed Silicon Valley startup called Intel. Leading Intel to market dominance as its president, chairman and CEO in the 1980s and 1990s, Grove became one of the most influential business leaders in Silicon Valley history.

Success to me is a system that bets on people like Andy Grove, some of whom might be waiting at American borders, right now. I want to see a lot more Andy Groves.

Micro Reads

⚛ European Scientists Set Nuclear-Fusion Energy World Record - Aylin Woodward and Jennifer Hiller, WSJ | At some point all those skeptical “nuclear fusion is the future of energy and always will be” types of gibes will have to concede that significant progress is happening. A donut-shaped tokamak device — it can heat gasses to 150 million degrees Celsius inside a vacuum, using magnetic fields to hold the plasma away from its walls — located at a UK facility in Oxfordshire “has produced the highest sustained nuclear-fusion energy ever recorded, European researchers said Wednesday.” Moreover, the success of the Joint European Torus is a harbinger of success for far larger ITER international fusion project “is expected to produce more energy than it takes in, in part because it will use superconducting magnets—rather than the copper ones used by JET—to generate its magnetic fields. Superconducting magnets use far less power.” And don’t forget the considerable private sector efforts: “Around 35 firms globally are racing to be the first to create net-energy machines and to commercialize them by delivering electricity to the power grid. Fusion companies have raised at least $4.3 billion toward the effort, according to company announcements and data tracked by the Fusion Industry Association and the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority.”

🌌 25 Theses on Starship, Space Tourism, and Human Futures Beyond Earth - David Brin and Joe Carroll, Contrary Brin | Here are a few of these “way-under-considered” assertions:

Starship’s main business will be delivering payload from Earth to LEO (& back), not beyond.

Most tourists will want access to 0g, but prefer partial gravity for most of their time in orbit.

“2001 wheel” won't minimize spin-queasiness. Best is a long, slow-spinning dumbbell.

The best way to start “mining the sky” is to recycle & reuse most mass now discarded by ISS.

Growing food in LEO can get us closer to living off Earth than putting people on Mars can.

📉 A Beijing think tank offered a frank review of China’s technological weaknesses. Then the report disappeared - Dennis Normile, Science | Based on the substance of that report, I’m not sure who disappeared it, the Beijing communists or American nationalists hackers. In any event, Science downloaded the report before it vanished:

China’s overall technological strength has gradually increased. … However, China still has a long way to go from being a quantitatively strong country in science and technology to being a qualitatively strong country in science and technology. … China still lags far behind the United States in terms of the number of highly cited papers and in paper originality. … Both China and the U.S. face losses from [technological] decoupling, both at the technical and industrial levels, but China’s losses may be greater at present. … A considerable number of overseas students choose to stay and develop their careers in the United States after obtaining STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math] doctorates in American universities.

💉 Covid vaccines: the race for a single shot to prevent new pandemics - Sarah, Neville, FT | Researchers are exploring a universal COVID super shot to protect against future cornonavirus variants. Mirroring the difficulties of formulating a once-and-for-all flu shot, scientists must grapple with a rapidly mutating virus and current immunity among the population. New tools and techniques — like injecting non-infectious particles to mimic coronavirus and induce an immune response — have researchers optimistic about creating a variant-proof jab in the next few years. The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease has handed out $36.3 million to three academic institutions for further research.

Nano Reads

▶ New Research Shows Genetically Modified Crops Could Significantly Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions - University of Bonn, Breakthrough Institute |

▶ Teleworking is here to stay and may raise productivity if implemented appropriately - VoxEU |

▶ Why Japan’s Automation Inc is indispensable to global industry - The Economist |

▶ What is nuclear fusion? - The Economist |

▶ Does Infrastructure Spending Boost the Economy? - Marios Karabarbounis, Richmond Fed |

▶ Immigration Powers American Progress - Institute for Progress |

▶ ALIAS equipped Black Hawk helicopter completes first uninhabited flight - DARPA |

▶ Can microdosing psychedelics boost mental health? - Meryl Davids Landau, National Geographic |

▶ The U.S. Army has released its first-ever climate strategy - Michael Birnbaum and Tik Root, WaPo |

Business and public investment are surging in the U.S. Is a productivity boom coming?

I appreciate you responding to my comment the other day with plenty more context and explaining your thinking, with sources and all. I wonder if you would be interested in factoring in Income Inequality in the US as part of this discussion?

My concern is that it seems like for some (rich) people, the line goes up much more than for other (poorer) folks. Such as: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2015/demo/real-household-income-at-selected-percentiles--1967-to-2014.html