🚀 Faster, Please! — The FAQ

A regular update that explains the mission of this newsletter

1/ What are you trying to accomplish with this newsletter? I’m trying to encourage a wealthier, healthier, and more fun America and world through ideas that promote greater and more significant scientific discovery and invention … leading to greater and more significant business innovation … leading to faster worker productivity growth … leading to faster overall economic growth. Much faster. (Also important: a pro-progress, techno-optimist culture.) Let’s get the cool sci-fi future we were promised! Flying cars? Sure. But also a world where every economy is an “advanced” economy, where lifespans and healthspans are longer, where abundant clean energy and a space economy mean humanity is limited only by our effort and imagination. A world of less suffering and more freedom, choice, and opportunity. Faster, please!

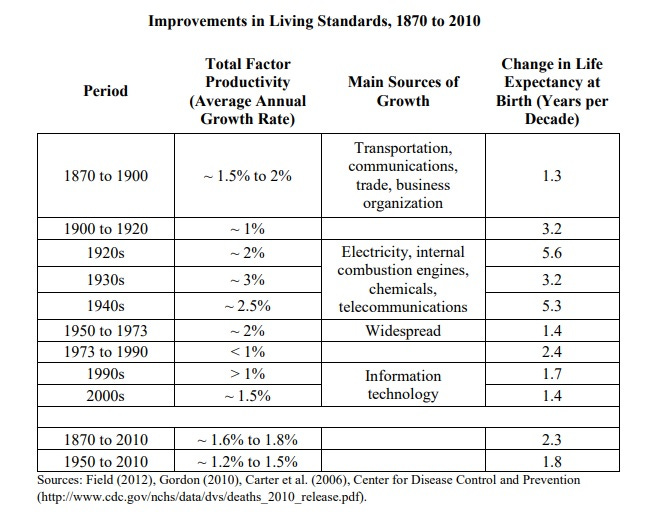

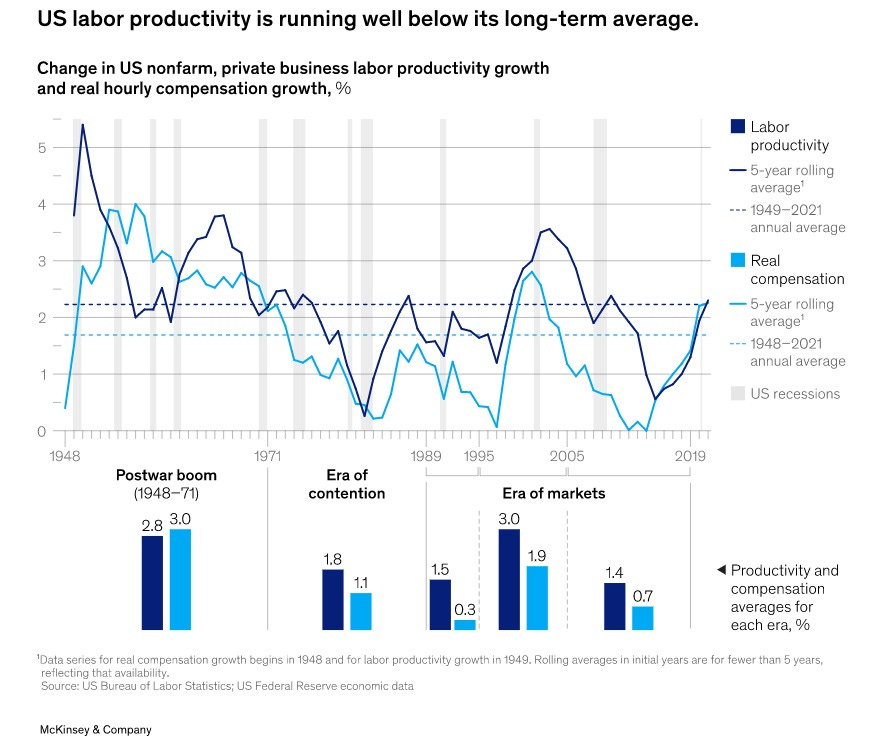

2/ You write a lot about economic productivity growth. What is that, and why is it so important, exactly? Here are two quotes, each from a Nobel laureate. The first is from New York Times columnist Paul Krugman: “Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” The second is from the University of Chicago’s Robert Lucas: “Once you start thinking about growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.” Over the long run, faster economic growth is driven by faster productivity growth: the amount of goods and services produced from each unit of labor input.

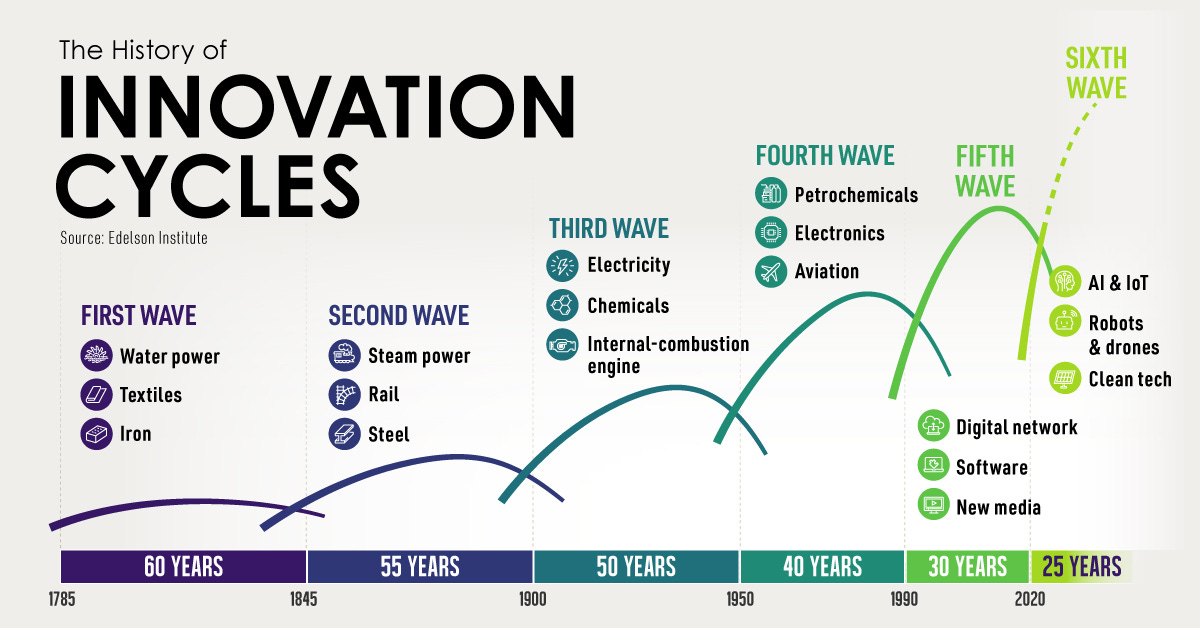

3/ But what does productivity growth have to do with scientific discovery and technological innovation? A lot! A country’s economy can become more productive by its workforce generating more hours of work and giving that workforce more equipment to do its job. But of greater importance than those things is the part of productivity growth driven by technological progress and business process innovation (known as total factor productivity growth). And tech progress is driven by scientific progress. Advances “in thermodynamics, physical chemistry, and electromagnetism, [led] to the introduction of electricity generation and internal-combustion engines,” notes an excellent CBO analysis. And we don’t get microchips and the IT revolution without a better understanding of physics.

4/ Where does public policy come into play? Doesn’t all this new science and technology kind of just happen with “Eureka!” moments? What we do as a society plays a huge role. That’s why I write a lot about science funding, regulation, immigration, infrastructure, and tax policy. But here is the Deep Magic: Letting innovators innovate. This may seem obvious, but witness the backlash to generative AI. Already there are calls for pauses, nationalization, and other restrictions. Progress still relies on government letting innovators innovate — and being rewarded for that innovation — despite the disruption that necessarily ensues. Economist Deirdre McCloskey calls this arrangement the Bourgeois Deal, which has three acts:

Allow me, in the first act, to have a go at innovating in how people travel or buy groceries or do open‐heart surgery, and allow me to reap the rewards from my commercial venturing, or absorb the losses (darn it: isn’t there something the government can do about that?). I agree, reluctantly, to accept that in the second and third acts my supernormal profits will dissipate, because my lovely successes from innovating the department store or devising the laptop will attract imitators and competitors. (Those pesky imitators and competitors. Hmm. Maybe I can get the government to stop my competition.) By the end of the third act, I will have gotten rich, thank you very much, but only by making you, the customers, very rich indeed.

5/ What is the Great Stagnation and when did it happen? The year 1973 marked a turning point in the boomy postwar economy. The era of fast productivity growth ended — much to the surprise of economists and experts of all sorts. As Nobel laureate economist William Nordhaus wrote in 2004: “The productivity slowdown of the 1970s does appear to be a major distinguishing feature of the last century, and particularly of the period since World War II.” And other than the PC + internet productivity upturn from the late 1990s through the early 2000s, the Great Downshift has lingered on.

6/ Do we know why the Great Downshift happened and then continued? There are worse explanations than a) we’ve squeezed all the gains from the big inventions of the 20th century — from electrification to the IT revolution — and now we’re waiting for the Next Big Thing, and b) big ideas are simply getting harder to find, requiring more researchers and resources. Actually, those are good explanations. And to those, I would add our poor policy choices, such as too little R&D funding and too much regulation that makes it hard to innovate and build in the physical world as opposed to the digital one. (Much of this was an overcorrection to environmental concerns that emerged in the 1960s.)

7/ Why are you confident that after a half-century it’s possible to turn the Great Downshift into a Great Upshift? Several reasons:

A lot of Next Big Things seem to be happening right now: AI (machine learning), genetics (CRISPR), energy (advanced nuclear fission, fusion, and deep geothermal), and space (reusable rockets).

Economists seem to have a better understanding of the reasons behind the Great Downshift, both macroeconomic and policy related (as noted above). There’s greater confidence that our policy decisions can generate faster progress.

Crises can create opportunity for action — and we have a plate full of crises today: A once-in-a-century pandemic, the threat of a chaotic climate, energy shocks from war in Europe, the challenge of a rising geopolitical rival in China, the inadequacy of an economy that does too little for too many — all of this presents an opportunity for big change.

8/ Is there any hard evidence that a pro-progress agenda can really happen? Yes! This Congress has passed bills to improve infrastructure and boost federal science investment — with increasing productivity growth as an acknowledged goal for both. Pro-build housing reform — sometimes it seems as if all our productivity problems are about housing — is finally making real progress at ground zero: California. The vaccine production success of Operation Warp Speed had led to calls for similar efforts to be applied to other health problems. And there might be no greater sign of progress that the revival of interest in nuclear energy. We are finally recognizing that our climate change problem is really a clean energy problem. On the left, policy journalists are pushing a pro-build “supply-side” progressivism. And on the right … well, the GOP embracing techno-optimist Elon Musk has to be a good sign, you know?

9/ If we don’t get a New Roaring Twenties, followed by a Thrilling Thirties, and Fantastic Forties, what probably went wrong? Maybe the aforementioned technologies turn out to be less consequential than they appear right now. Or maybe policy is unsupportive of their further development, emergence, and commercial diffusion throughout the economy. Maybe we do too little to support R&D by government and business. Maybe we don’t correct for a half-century of environmental overcorrection and continue to associate economic growth with degradation of nature. Maybe we are unwilling to accept the risks that come with change, whether from technological disruption or from an open economy that embraces immigration and trade. The forces of the status quo and fatalism win. Blech!

10/ That sounds terrible. Why would we let that happen? A theory: Just as an individual's future behavior is to some extent governed by his self-image of the kind of person he hopes to be, so too society. Our image of the future influences and inspires our intentions, actions, and attitudes today. As Dutch futurist Frederick Polak famously put it, any culture “turning aside from its own heritage of positive visions of the future, or actively at work in changing these positive visions into negative ones, has no future.” We need at least a vague notion that all this hard work and risk-taking will pay off in a better world. Not only do we need politicians to engage in this sort of image communication, but our culture, too.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Great Stagnation. At America’s 2076 Tricentennial, let’s make sure Americans can look back at five decades of tremendous and indisputable problem-solving and progress.

Micro Reads

▶ At long last, the glorious future we were promised in space is on the way - Eric Berger, Ars Technica | To be sure, that is a lot of hardware that has yet to be built and tested. But when we step back, there is one inescapable fact. With SpaceX's fully reusable Starship, and now Blue Moon, NASA has selected two vehicles based around the concept of many launches and the capability to store and transfer propellant in space. This is a remarkable transformation in the way humans will explore outer space—potentially the biggest change in spaceflight since the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957. It has been a long time coming.

▶ A Paralyzed Man Can Walk Naturally Again With Brain and Spine Implants - Oliver Whang, NYT | In a study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, researchers in Switzerland described implants that provided a “digital bridge” between Mr. Oskam’s brain and his spinal cord, bypassing injured sections. The discovery allowed Mr. Oskam, 40, to stand, walk and ascend a steep ramp with only the assistance of a walker. More than a year after the implant was inserted, he has retained these abilities and has actually showed signs of neurological recovery, walking with crutches even when the implant was switched off. “We’ve captured the thoughts of Gert-Jan, and translated these thoughts into a stimulation of the spinal cord to re-establish voluntary movement,” Grégoire Courtine, a spinal cord specialist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne, who helped lead the research, said at the press briefing.

▶ Ultrasound can trigger a hibernation-like state in mice and rats - Michael Le Page, New Scientist |

▶ Sam Altman’s World Tour Hopes to Reassure AI Doomers - Morgan Meaker, Wired | Before the trip, Altman said on Twitter the purpose of his world tour was to meet with OpenAI users and people interested in AI in general. But in London, it looked like the company was also trying to cement its leader’s reputation as the person who would usher the world into the AI age. Audience members asked him about his vision for AI, but also about the best way to educate their children and even how to build life on Mars. In an onstage discussion with UCL professors, one panelist said she was here to represent humanity. Altman uncharacteristically jumped in to stress his company was not working against it. “I represent humanity too,” he said.

▶ Humanoid Robots Are Coming of Age - Will Knight, Wired |

▶ ‘We better figure it out': The politics trap that could slow a national AI law - ▶ Brendan Bordelon, Politico | Capitol Hill is rushing to regulate artificial intelligence before most members have even a basic understanding of the technology. And as momentum grows, the new AI push appears at risk of getting tangled in the same political fights that have paralyzed previous attempts to regulate technology.