🧗♂️ 'Friending bias' as the enemy of upward mobility

Like so many of America's problems, housing policy may be key to pro-progress reform

The notion of progress is central to the idea of the American Dream — as well as to this newsletter. You will live better than your parents: a life of greater wealth, health, opportunity, and choice. (Maybe even a life off-planet!)

The aspect of rising living standards that economists mostly focus on is growth in personal incomes. One kind of economic mobility is “relative mobility,” which measures how a child’s ranking in a society’s income distribution compares to that of their parents.

Then there’s “absolute mobility,” which I think better captures the essence of the American Dream. After all, one could imagine a scenario in which it became easier to move from bottom to top even as the bottom became poorer in absolute terms. So rather than income rank, absolute mobility looks at whether your income is higher or lower than that of your parents at the same age.

Even if I had no idea of my parents' adult income, I would know my living standards are higher today than when I was a kid. I grew up in a working-class neighborhood in a tight, two-bedroom house. No air conditioning, no color TV or cable until I was in high school, no vacations out of the Midwest, much less out of the county. Did I mention no A/C?

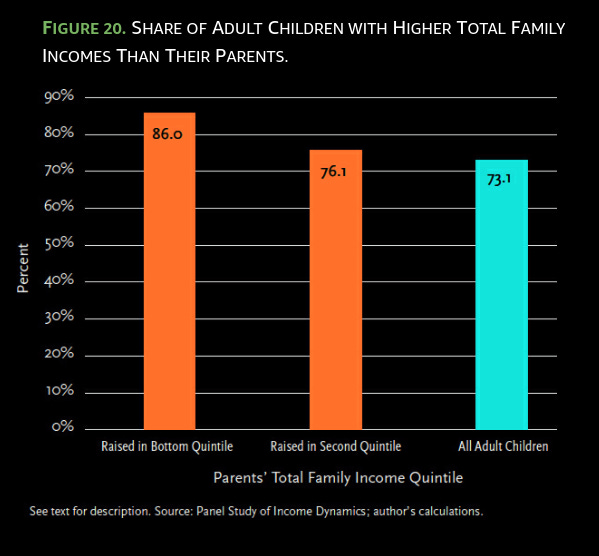

That my life today is way better than as a kid — that I have experienced significant absolute upward mobility — hardly makes me unusual for an American, as seen in this chart from The American Dream Is Not Dead (But Populism Could Kill It) from my AEI colleague and economist Michael Strain:

The reason I’m indulgently telling you about my hero’s climb up the mobility ladder is because of a big new study about “friending bias” from Harvard University economist Raj Chetty and a team of colleagues. The research finds that absolute upward mobility for lower-income kids is helped by having friendships with kids who are better off. As Chetty told the New York Times: “Growing up in a community connected across class lines improves kids’ outcome and gives them a better shot at rising out of poverty.”

There’s a striking difference in outcomes between poorer kids who grow up in a community where most of their friends are in the lower half of the socioeconomic distribution vs. those who grow up in a community where their friends mostly come from the upper half. Again, from the Times:

The study found that if poor children grew up in neighborhoods where 70 percent of their friends were wealthy — the typical rate of friendship for higher-income children — it would increase their future incomes by 20 percent, on average. These cross-class friendships — what the researchers called economic connectedness — had a stronger impact than school quality, family structure, job availability or a community’s racial composition. The people you know, the study suggests, open up opportunities, and the growing class divide in the United States closes them off.

What is the mechanism driving these results?

There seem to be three main mechanisms by which cross-class friendships can increase a person’s chances of escaping poverty, Chetty told [Times reporter David Leonhardt]. The first is raised ambition: Social familiarity can give people a clearer sense of what’s possible. The second is basic information, such as how to apply to college and for financial aid. The third is networking, such as getting a recommendation for an internship.

It’s a clever study with data derived from the 21 billion friendships of 72 million Facebook users. It also feels intuitively correct. Whether friendships are more important than all those other factors, I can’t say. But such connections sure seem significant based on my personal experience. For example: I didn’t attend my local public schools and had few neighborhood friends, especially once I aged out of Little League. I went to a private Christian school, from first grade through 12th, that had a mix of kids from across the income spectrum. (My church helped fund my tuition.) While some of my close friends in high school had a similar background as mine, just as many came from upper-middle class or wealthy families: big houses, backyard in-ground pools, lake homes that were nicer than my everyday home. And these kids traveled. I consistently experienced or heard about a life far different, helping provide me that aspirational “sense of the possible.”

Of course, every problem doesn’t have an obvious solution or generate a clear five-point policy agenda. But there are some things policymakers, more at the local level, might try, such as more diverse K-12 schools created by drawing school districts so that they include both poorer and richer neighborhoods. And those schools should be designed with an open architecture to “encourage serendipitous socializing.” (This study is hardly a vote of confidence in hybrid learning.) The researchers also suggest, the Times notes, “specific efforts — like public parks that draw a diverse mix of families — to encourage interactions among richer and poorer people.”

But probably the most significant approach involves housing, just as it seems with every big problem facing America. We need land-use reform to boost supply, especially in some of the most productive and highest earning regions. You can’t make friends if you’re not even physically present. (Or as the researchers put it. “Economic connectedness is determined by the combination of exposure and friending bias.”) Without the ability to create more supply, I’m not sure what housing subsidy schemes would accomplish.

I’m reminded here of the important findings about upward mobility found in Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success by economists Ran Abramitzky (Stanford University) and Leah Boustan (Princeton University). This is the headline grabber: “Children of immigrants from nearly every country in the world are more upwardly mobile than the children of US-born residents who were raised in families with a similar income level.”

But, you might ask, why is this so? Again, Abramitzky and Boustan:

As striking proof that geography matters, we find that children of immigrants outearn other children in a broad national comparison, but they do not earn more than other children who grew up in the same area. In terms of economic fortunes, the grown children of immigrants look similar to the children of US-born parents who were raised down the block or in the same town. This pattern implies that the primary difference between immigrant families and the families of the US born is in where they choose to live. One implication of our findings is that it is very likely that US-born families would have achieved the same success had they moved to such high-opportunity places themselves. In fact, we find that the children of US-born parents who moved from one state to another have higher upward mobility than those who stayed put: their level of upward mobility is closer to (but not quite as high as) that of the children of immigrants who moved from abroad.

What might pro-housing policy look like? In the 2019 analysis “Removing Barriers to Accessing High-Productivity Places,” economist Daniel Shoag of the Harvard Kennedy School and Case Western Reserve University offers ideas for reform:

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also conduct short, sharp Q&A with interesting thinkers. Here are some recent examples of those interviewees:

Economist Tyler Cowen on innovation, China, talent, and Elon Musk

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on the origins of economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

AI expert Avi Goldfarb on machine learning as a general purpose technology

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy