🚅 Airships, hyperloops, and intercity rocket travel

Thinking about the future of US transportation

A natural question given the focus on this newsletter: What should the future of American infrastructure look like? Especially in transportation, what sorts of upgrades and additions might we have to prepare for? Of course, when you begin to speculate, those imaginings are quickly constrained by the current reality of how hard it is to build with atoms rather than bits in this country. Anyway, let’s take a look at a few possibilities, and what it would take to make them happen:

➡ Flying cars as air taxis. Flying cars don’t need to be something out of The Jetsons or Blade Runner to exist in our world. As long as your expectations are reality-based, you’ll be able to appreciate some recent significant advances. In October, CNBC reported that Delta Air Lines “joined the list of airlines backing EV technology startups, with a $60 million investment in Joby Aviation, a company developing electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, intended to operate as an air taxi service.” Then in November, the FAA proposed standards for Joby’s aircraft, “paving the way for the first official certification of the novel electric aircraft,” according to Bloomberg.

And earlier this month, Stellantis NV, the European carmaker that owns Chrysler and Fiat, agreed to manufacture an eVTOl designed by Archer Aviation up to $150 million of equity capital. What sort of timeline are we talking about for this emerging sector? As one Wall Street analyst told CNBC, “We think that you’ll see small amounts of [eVTOL] operations starting in the 2025 timeframe, with certifications hopefully happening in 2024. But for you to see a lot of aircraft flying overhead, it’s probably going to be more likely into the 2030s.”

Along those lines, this analysis from my early 2022 5QQ exchange with transportation David Levinson remains relevant:

Since the 1920s people have dreamt of an autogyro in every garage. It was a key mode of transport in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City proposal in 1932. For decades, Los Angeles required high-rises to have flat-roofs to enable helicopter landings. With advances in automation and controls, AI, and electrification, it’s getting closer. As drones become more widespread, the key technologies advance, and society’s willingness to tolerate a significant rise in air travel also increases. But it’s not likely to mix well with cities, in contrast with suburbs and rural areas, because of the crowding and high density. So it should emerge first where traveling fast and directly is more important, which are lower density areas with greater distances to be covered.

➡ High-speed rail. This is a classic case of not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good or, in this case, letting some vision of a continent-spanning, interconnected system where every major city gets a stop — you could board in Boston and get off in Vancouver — detract from a more constrained, but also more realistic blueprint. Something more like this:

In this map, from transit expert Alon Levy, the red lines are high-speed rail, ranging from 150 to 200 miles per hour, depending on population density and geography. In other words, it’s not an exercise in wishcasting. It’s not this map where everybody gets a superfast train:

So, for instance, all the lines are not connected. Nor is every large population center connected. (Sorry Denver and Salt Lake City.) Levy: “Sometimes the cities are just too small or too far apart.” Nor will anything short of hyperloops really threaten air travel for long-range dominance. Levy:

The median distance of a domestic American air trip is well above the point beyond which HSR stops being competitive with air travel. Counting only city pairs at a plausible HSR range of around 4-5 hours, maybe a bit more for New York-Atlanta, my estimate is that about 20-25% of domestic US air trips can be substituted by rail. … However, the fact that people will continue flying until vactrains are invented does not make HSR useless or unnecessary. After all, people fly within Europe all the time, even within individual countries like France. Not only do people fly within Japan, but also the country furnishes two of the world’s top air routes in Tokyo-Sapporo and Tokyo-Fukuoka. As an alternative at its optimum range of under about 1,000 km, HSR remains a solid mode of travel.

➡ Ultra-high speed rail, or hyperloops. Back in 2020, New York Times reporter Eric A. Taub wrote a story that provided some reason to hope that theoretical transportation system — people- or cargo-filled pods whooshing via magnetic levitation through low-pressure tubes and tunnels at nearly the speed of sound (a "cross between a Concorde and railgun and an air hockey table,” according to Elon Musk) — might be more than a Muskian flight of fantasy. In the piece “A Step Forward in the Promise of Ultrafast ‘Hyperloops,’” Taub wrote about Virgin Hyperloop becoming the first company to conduct a test of the technology, whisking two volunteers at over 100 m.p.h. for 6.25 seconds. As Jay Walderm, the company’s chief executive said at the time, “The U.S. Interstate Highway System, which began in 1956, cannot be the end of our imagination in terms of how we move around. [With hyperloop], “we can have a fundamentally different transportation system.”

But when? In September 2022, Taub followed up with “Is the Hyperloop Doomed?,” a piece documenting all manner of setbacks in a number of embryonic projects. Over the course of last year, for example, Virgin Hyperloop cut 111 staffers (about half its employees), changed its focus to cargo rather than passengers, stopped development of a certification center in West Virginia, changed leadership, and returned to its previous name of Hyperloop One. Another company, Los Angeles-based Hyperloop TT, based in Los Angeles, “had as recently as 2019 promoted its work building a system in the United Arab Emirates, but has shifted to other projects, said Andrés De León, its chief executive. Its U.S. project furthest along in development is planned for the Great Lakes region, where the company is looking for private funding to conduct a two-year environmental study before trying to build out the route.”

Then there’s Musk. Back in November, he dismantled a “hyperloop prototype” test tunnel across the street from SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, and turned it into a parking lot. Well, at least Taub included an upbeat expert quote. “There are so many good things about pursuing hyperloop that, even if it’s not the answer, it will have generated lots of ideas and allowed people to think things through,” said Hugh Hunt, professor of engineering dynamics and vibration at the University of Cambridge. And, of course, we wouldn’t want China to win the Hyperloop Race.

Again, Levinson:

We can’t build subways or high-speed rail lines at reasonable cost in the US, and we are supposed to try to build an unproven technology? Hyperloop is a moving target, but if we mean maglev with small carriages in evacuated tubes, I don’t think so. The maglev is slowly getting deployed in places, Shanghai has had a small line operating for years, which I rode. Japan has a major line under construction now (to open 2027). But making them go even faster by putting them in tubes with the air removed (to reduce air resistance and increase speed) is untested and brings new engineering challenges. Using small carriages, with sharp acceleration and deceleration, as originally proposed, and spacing them close together, brings new risks.

➡ Airships. These graceful floating and flying whales of the sky are a staple of alt-history and alt-reality fiction. When they show up in a story as a totally normal mode of transportation, you know you’re journeying down a path not taken here on Earth One. The obvious historical pivot point is the deadly May 6, 1937, Hindenburg disaster. But if the economics of airships were better than emerging winged alternatives — 18 months before the fiery accident, the Pan American Airways’ M-130 China Clipper launched the modern age of international airplane travel by making the first scheduled flight across the Pacific — even the cinematic conflagration might have been just a mere bit of turbulence. The Titanic sinking isn’t what eventually ended the era of transatlantic passenger travel, after all.

Their coolness factor always makes airships a comeback candidate. And maybe now they finally make sense again thanks to some recent technical advances that enable a new generation of flying machines to be something more than floating billboards. For example: Google co-founder Sergey Brin has been funding an electric airship project, Lighter Than Air Research. LTA’s 600-foot Pathfinder airship, reports the Financial Times, will use 3D printing and carbon-fiber tubing “to reduce costs and speed up production” in an attempt to serve some niche markets such as humanitarian relief and a “green” alternative to existing air- or sea-freight options. IEEE Spectrum reports that Pathfinder’s overcovering will be made from a three-layer laminate of synthetics that are similar to the sails in racing boats. Beyond the advances in materials and production, IEE quotes LTA’s chief technical officer, who points out that Pathfinder is a “fully electric fly-by-wire aircraft, which is not something that was possible 80 years ago.” The same goes for the lidar units installed on top of each helium gas cell to help pilots better orient the airship, which will be able to carry with an expected capability to carry nearly 100 tons up to 10,000 miles.

And as far as PR problems for airships go, there are plans for a $5 million around-the-world airship race with the finish line in Paris. Also, some entrepreneurs have plans for airships that cater to the superwealthy with spacious and leisurely cruises to exotic destinations, such as the Arctic. Perhaps when the rest of us see the elite boarding the blimps, we’ll take it as a sign the whales have returned for good.

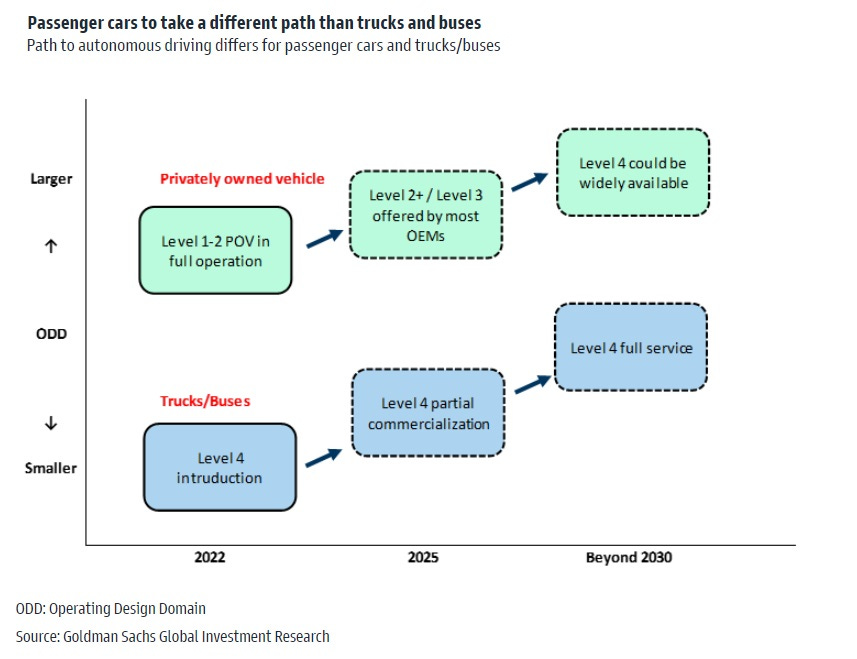

➡ Self-driving cars and trucks. No, we don’t yet live in a country where there are a million or more self-driving cars already on the road, including the million robo-taxis once predicted by Elon Musk. But progress is being made. Cruise and Waymo, Axios recently reported, both offer tax service in Phoenix and San Francisco and are looking to expand in other cities, while also further opening up their cars to the general public. Technically, these are “Level 4” cars, meaning that are self-driving in certain places and under certain circumstances. For example: Waymo robotaxis will be shuttling Super Bowl fans in Phoenix, but the venue itself — State Farm Stadium in Glendale, west of Phoenix — isn't in Waymo's service area. That wouldn’t be a problem with a Level 5 car, which also might now have a steering wheel. So when will

self-driving cars truly take off, both in capabilities and ownership? Goldman Sachs presented this timeline in a report last October:

The question is whether autonomous vehicles higher than Level 3 (“the driver does not always have to be monitoring driving conditions [and in] situations where driving conditions exceed preset parameters, the vehicle hands control back over to the driver with a few seconds warning”) are meaningfully worth the effort technologically, socially and profit-wise. On the technology side, advances are needed in both hardware (sensors, etc.) and software. In particular, it is vital that output from AI can be logically explained in order to manage the risk of an accident occurring (XAI, Explainable AI). On the social side, legal frameworks need to be updated, and discussion needs to take place on moral standards, such as the Trolley Problem. These social factors are likely to vary greatly by region. In terms of profitability, the base assumption is that consumers will be willing to pay monthly service charges for the value added by self-driving functions. We estimate Level 3 and higher self-driving cars will account for roughly 15% of sales in 2030 (0% in 2020).

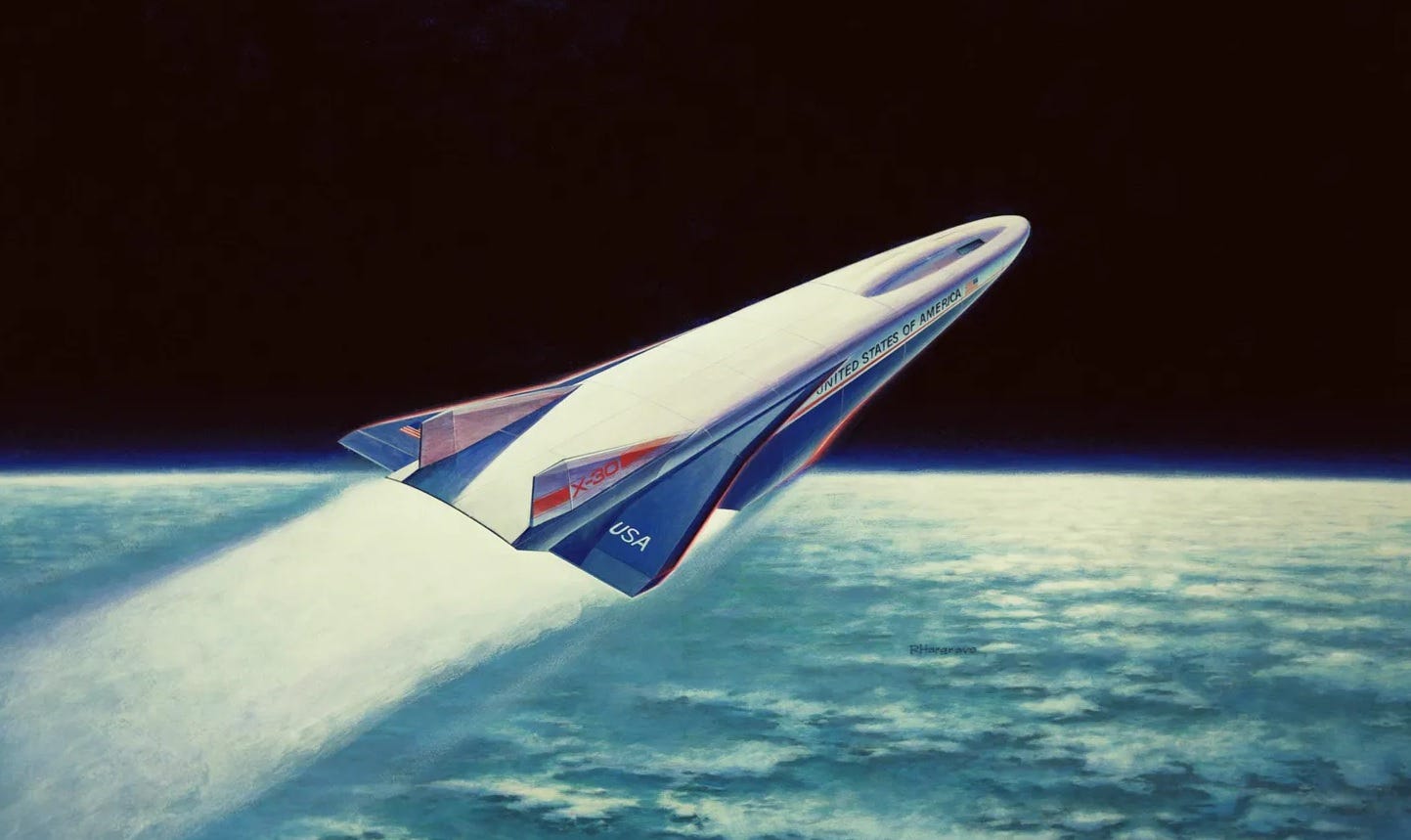

➡ Intercity rocket travel. As I’ve noted in recent issues, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Ronald Reagan imagined a future where space planes or rockets would transport passengers around the world at amazing speeds. In Reagan’s case, his ambition became national policy. Unfortunately, the National Aerospace Plane was unable to match the success of the earlier program to build a stealth combat aircraft and was finally canceled in 1993.

But as with so many potential space activities, the sharp decline in launch costs means it’s again OK to dream of long-distance flight times a tenth of what airline passengers experience today. With a decline in launch costs from $1,500/kg today (SpaceX) to $100/kg by 2040, Citigroup thinks the market for inter-city space passenger travel could be worth almost $7 billion of revenues for operators assuming that it can capture roughly a fifth of the long-haul jet market for businesses and “ultra high net-worth individuals.” Cargo rockets would be an even bigger $20 billion annual business. But should launch costs decline to the SpaceX Starship target of $10/kg), the banks think inter-city space travel costs can be competitive enough to capture a share of first-class and business-class travelers on long-haul wide-body routes. Then we’re talking about a $50 billion-a-year business.

Now let’s think about the obstacles, beyond technological hurdles like better AI and lower launch costs, to the above options. Many of them should be familiar to long-time and regular readers. California’s failed attempt to build HSR between Los Angeles and San Francisco was a costly and long-running boondoggle thanks to politics-driven decision-making and regulatory delay. Without regulatory and permitting reform at all levels, good luck building lots of HSR lines, much less a hyperloop. Indeed, all of the above modes of transit require lots of building and lots of new infrastructure. An extensive air taxi network needs vertiports, charging, and connectivity to existing transportation hubs. A world of autonomous driving not only needs well maintained roads, but ones with features that give AVs help, such as highly reflecting striping and, eventually, replacing stoplights and street signs “with a digital transportation-management system that feeds key information, such as speed limits and turning restrictions, directly to vehicles,” according to McKinsey. And whether the train is an HSR or hyperloop, new train infrastructure and land — as the California project showed — with hyperloops needing lots of long straightaways. And, as Taub noted in that more NYT recent piece:

While new types of transport such as electric vehicles can easily be integrated into the existing system of roads, a hyperloop system would require creating an entire infrastructure. That means constructing miles-long systems of tubes and stations, acquiring rights of way, adhering to government regulations and standards, and avoiding changes to the ecology along its routes.

One more thing: It’s not just all those environmental laws from the late 1960s and early 1970s. Policy analyst Eli Dourado recently made a persuasive argument that a revitalized airship sector would benefit greatly if the FAA reversed its prohibition on using hydrogen — cheaper and more plentiful than helium — as a lifting gas for cargo airships.

Bottom line: All the above, with the exception of the hyperloop concept, either are happening or can be realistically imagined happening with a bit more investment and regulatory reform — and time. While for the moment we seem back to focusing on innovation in bits, thanks to ChatGPT, there’s plenty happening in the physical world, too.

Electric cars, electric planes, electric trains, electric heat pumps, electric ranges, electric this, electric that. And he have to shut down all those nasty nukes, and combined cycle natgas plants, and, of course, coal plants. Do it all with windmills will we?

All cool stuff, but sadly requires lots of government and political support. On a local level I would love to see a self contained machine for resurfacing roads a lane at a time, grinding up the potholed and cracked existing asphalt and reconstituting it with newer elastic materials and applying the new surface all in one step maybe even with liquid nitrogen cooling so the new surface is immediately drivable.

In addition but not transport, but having forest fire-fighting autonomous drones and more agricultural robots would be nice to see.