🔙 The Smithsonian’s dreary 'Futures' exhibition is stuck in the eco-pessimist 1970s

Also: Five Quick Questions for . . . transportation expert David Levinson

"We must vastly widen our conception of possible futures. To the rigorous disciplines of science, we must add the flaming imagination of art." - Alvin Toffler

In This Issue

Long Read: The Smithsonian’s dreary Futures exhibition is stuck in the eco-pessimist 1970s

5QQ: Five Quick Questions for . . . transportation expert David Levinson

Micro Reads: Driverless tracts, China, clean energy investment, and more . . .

Long Read

🔙 The Smithsonian’s dreary Futures exhibition is stuck in the eco-pessimist 1970s

I understand why the designers of the Smithsonian Institute’s new 32,000 square-foot Futures exhibition — billed as a “guide to a vast array of interactives, artworks, technologies, and ideas that are glimpses into humanity’s next chapter” — would cover the walls inside the reopened Arts and Industries building on the National Mall with dozens of future-themed quotes. That’s not what perplexed me when I toured Futures with my family over the holidays. The quotes themselves are a fun, if a bit predictable, design choice.

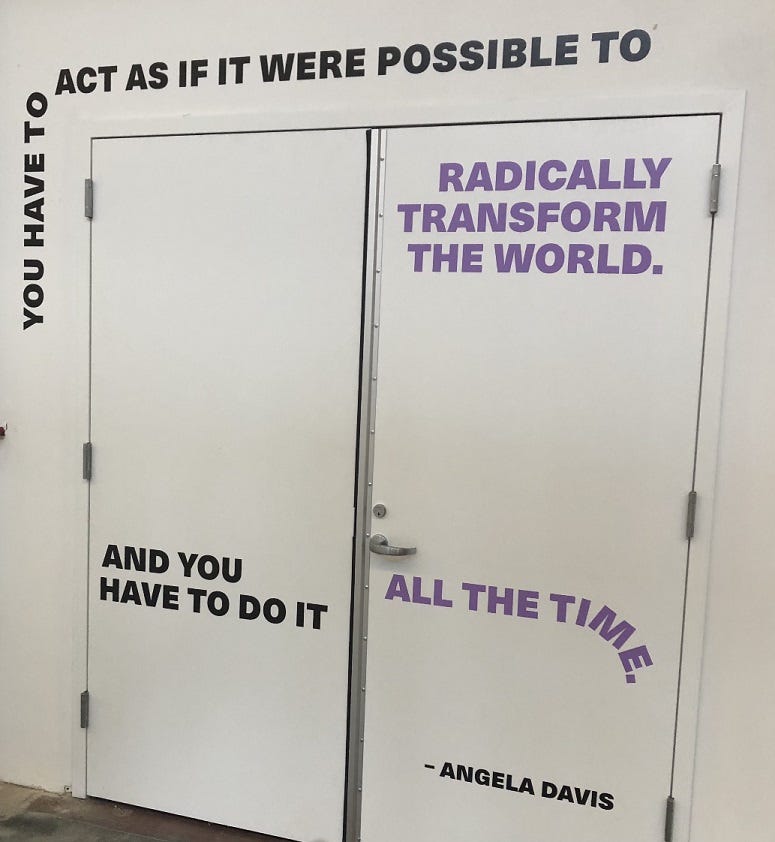

No, what left me confused was the Smithsonian’s selection of authors. If I were the Futures project manager, I would have included a quote or two from space entrepreneurs Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, CRISPR developers and Nobel laureates Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, mRNA vaccine pioneers Ugur Sahin and Ozlem Tureci, or the Apollo 11 crew — certainly before including quotes from Dolly Parton and Audrey Hepburn. Or from León “Argentina’s Bob Dylan” Gieco. Or, appallingly, from Angela Davis, the notorious 1970s radical and communist. (Indeed, Davis was such an apologist for repressive communist regimes that she was a recipient of the Soviet Union's Lenin Peace Prize.) Including a Bill Gates quote doesn’t offset Davis.

If only the poor judgment demonstrated by the selection of quotes were the exhibition’s low point. There’s a much bigger problem with Futures: The Smithsonian is actually attempting to present an optimistic vision of the future. No dystopian exhibits showing a shattered Earth beset by overpopulation, growing poverty, resource scarcity, or a runaway climate. Although 2022 is the year in which the 1973 dystopian film “Soylent Green” is set (I wrote about it in the previous issue of Faster, Please!), Futures doesn’t explicitly warn of such scenarios of impending doom.

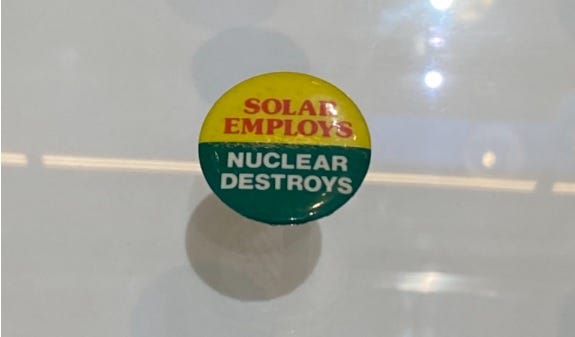

But Futures is too influenced by the 1970s “limits to growth,” Spaceship Earth, anti-capitalist, environmentalist futurism that emerged in response to such fears. That vision is neatly captured in a display of buttons from that era with messages such as “Recycle or Die,” “Consume Less,” and “Solar Employs, Nuclear Destroys.”

As Emory University historian Patrick Allitt writes in A Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism:

The idea of sustainable development, or the steady-state economy, caught on in the 1970s, and has often reappeared in recent decades. . . . In 1973 English economist E. F. Schumacher (1911–1977) published Small Is Beautiful, which rapidly became a cult classic in America and around the world. [Schumacher argued that society] must become decentralized, must give up an economy based on greed and envy, and must restore the dignity of work and the human scale. . . . Labor-saving devices were not necessarily improvements under these circumstances, and the achievement of leisure was not necessarily a desirable goal. Mechanization that robbed the traditional craftsman of his skill, far from being a manifestation of progress, was a crime. . . . What would a society look like if it actually acted on the proposals of The Limits to Growth and Small Is Beautiful? Ernest Callenbach’s futuristic novel Ecotopia (1975) drew heavily on these sources. In the story, Ecotopia is the name of a separate country, made up of Northern California, Oregon, and Washington, which has seceded from the rest of the United States. It has closed its borders and become completely estranged from the materialistic and growth-obsessed United States. . . . Ecotopia consists of many small, self-contained local communities using simple technologies. There are electric monorail trains but no cars, and the streets are quiet. It’s possible to hunt deer close to downtown San Francisco. Clothes are simple, all fibers are organic, food is wholesome and locally grown, schoolchildren do farm work as well as study, and everyone is committed to a sustainable no-growth economy

There’s a lot of the Ecotopia vision in Futures. Especially in these exhibits:

The “Coin-Operated Wetland” by Australian artist Tega Brain that demonstrates how wash machines could be used to create a closed wastewater system for growing a garden of wetland plants.

The sign leading into the “Futures That Work” section wonders if “we’ll harness the power of renewables [meaning winds and solar], focusing our creativity on sustainable cycles, rather than endless growth.” Quite the Thunbergian notion.

A wall of bricks made from mycelium, the root-like fibers of mushrooms. “This organic material can be grown into a shaped mold and is entirely compostable at home. Many architects and designers are exploring this novel material as a way to create biodegradable structures . . . [and] reduce our permanent impact on the Earth.”

“Will the future be handmade?” asks one exhibit. “Making things by hand is slow compared to machine production. Craft has value in itself, though. It connects us to the past and provides an alternative to an on-demand consumer culture.” It features a collection of textiles meant to show “how adapting traditional techniques in indigo dying, pattern making, and material use” can meet modern needs.

One of the 32 solar panels that President Jimmy Carter had installed on the White House roof in 1979, later removed during the Reagan administration.

A somewhat random display about Cesar Chavez and his late 1960s grape boycott.

An exhibit about making healthcare more affordable by manufacturing medicines such as insulin on a “grassroots basis” through community labs. Visitors are told the movement “to decentralize” science is gaining momentum.

An exhibit featuring a “deli of the future,” described thusly:

Reduce, reduce, reduce, reduce. To be fair, Futures is not quite as dreadful as I have, up to this point, made it seem. There’s a fun collection of tchotchkes from various 20th century World’s Fairs. There’s also a display of costumes from Marvel's 2021 film Eternals. Not sure what those have to do with the future, but they were fun to see up close. Also: This cool Virgin Hyperloop Pegasus XP-2 Pod:

Yet even this fits into the “monorail but no cars” Ecotopia vision. Then again, at least this exhibit mentions a company, Virgin. Overall, though, it would be easy to conclude from Futures that private enterprise doesn’t play much of a role in building the future. I previously mentioned the absence of Musk and Bezos from the collection of future-themed quotes. In the displays, as well, Futures seems to go out of its way to avoid mentioning Corporate America. A display about the future of internet access mentions Loon, a project to provide access to remote areas via balloon. Futures calls it “Project Loon from X, the Moonshot Factory.” No mention of the fact that the now-shuttered project, as well as X, are owned by Alphabet, the parent company of Google.

This is my biggest gripe: A tour of Futures gives little to no hint (a) that America has again returned to manned space flight; (b) that Musk’s SpaceX, not NASA, is responsible for a historic reduction in launch costs that could revolutionize manned exploration and space economics; (c) that there’s renewed global interest in nuclear power, and major advances being made in nuclear fusion and geothermal; (d) that there’s this revolutionary genetic editing technology called CRISPR that could do wonders for human health and lifespans; (f) that technologies such as carbon capture and geoengineering, not to mention nuclear and geothermal energy sources, provide a pro-abundance way of dealing with climate change; and, most inexplicably perhaps, (g) that breakthrough mRNA vaccines have blunted the current pandemic and hold huge potential to create super-vaccines for the coronavirus and other viruses. What’s more, there’s no recognition from Futures that economic growth and technological innovation have prevented those dire, 1970s scenarios from happening.

In other words, there’s an alternate image of the future — global, materially and energy abundant, market-oriented, multi-planetary — that Futures almost totally ignores. It’s an image that was widespread before the scarcity-driven 1970s. And it’s an image we should be thinking about again and getting excited about — perhaps for the first time since the 1960s and Apollo. But too much of Futures is trapped in the anachronistic “Small is Beautiful” mindset that is obsessed with resource scarcity, deeply skeptical of markets, rejects “consumerism,” accepts only solar and wind as legitimate energy sources, and views space as an expensive distraction from dealing with problems here on Earth. It’s not exactly a pessimistic vision of tomorrow, just a terribly crimped and unambitious one. And to me, not at all inspiring. What an opportunity the Smithsonian had — and utterly squandered.

5QQ

❓ Five Quick Questions for . . . transportation expert David Levinson

David Levinson teaches at the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney, he’s an honorary affiliate of the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, and he serves as an adjunct faculty at the University of Minnesota. He’s also the co-author The End of Traffic and the Future of Access. In addition, he authors the Transportist blog.

1/ America seems to be suffering a car crash epidemic. Why and what can we do about it?

There are many causes to this problem, which is another example of American exceptionalism, as crashes are declining in most developed countries (see figure, via David Zipper). Crashes result from high speed (wide lanes American lanes encourage fast driving, and high powered cars make it possible [to] drive faster than any posted speed limit — how high does your speedometer go?) mixed with slow reaction time (e.g. distracted and inebriated drivers, plus diminished ability to see what’s in front of them, higher speeds for instance focus drivers on distances far ahead rather than seeing what’s in their peripheral vision, or just in front of them). Fatalities are crashes where the speed (which has been increasing) and mass (which has also been increasing) are both too high. Two pedestrians colliding at walking speeds will not kill anyone. A car hitting a pedestrian at 40 mph will likely kill her. In fact, most cars are now trucks, significantly higher and heavier than cars of a few decades ago. I wrote about this a couple of years ago: 21 Solutions to Road Deaths

2/ When will we have a million self-driving cars on the road, ones that can at least be autonomous on highways?

It depends on what you mean by “autonomous”. In some ways we already have a million autonomous cars. Elon Musk will tell you his cars Autopilot systems are “Full Self-Driving” on highways now, and have been in beta mode for FSD on city streets for a number of years. General Motors will sell you "Super Cruise" in a number of Cadillac models, which allows hands off driving on 200,000 miles of highways. GM’s Ultra Cruise is supposed to launch hands off driving on 2 million miles of public roads (highways and streets) in 2023. In all of these cases, the driver is supposed to monitor the vehicle, so if by autonomous you mean the driver can safely go to sleep, we are not there yet, and are looking to late this decade.

3/ Will hyperloops ever be a real-world mode of transportation?

We can’t build subways or high-speed rail lines at reasonable cost in the US, and we are supposed to try to build an unproven technology? Hyperloop is a moving target, but if we mean maglev with small carriages in evacuated tubes, I don’t think so. The maglev is slowly getting deployed in places, Shanghai has had a small line operating for years, which I rode. Japan has a major line under construction now (to open 2027). But making them go even faster by putting them in tubes with the air removed (to reduce air resistance and increase speed) is untested and brings new engineering challenges. Using small carriages, with sharp acceleration and deceleration, as originally proposed, and spacing them close together, brings new risks.

4/ Will air taxis ever be a common mode of transportation?

Yes, but not this year. Since the 1920s people have dreamt of an autogyro in every garage. It was a key mode of transport in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City proposal in 1932. For decades, Los Angeles required high-rises to have flat-roofs to enable helicopter landings. With advances in automation and controls, AI, and electrification, it’s getting closer. As drones become more widespread, the key technologies advance, and society’s willingness to tolerate a significant rise in air travel also increases. But it’s not likely to mix well with cities, in contrast with suburbs and rural areas, because of the crowding and high density. So it should emerge first where traveling fast and directly is more important, which are lower density areas with greater distances to be covered.

5/ What's an important transportation issue that gets too little attention?

There are many issues that get too little attention, traffic safety you already noted. I’d add that even after we electrify the fleet and eliminate tailpipe pollution, cars will still pollute and be hazardous. Today air pollution from vehicles kills a similar number as crashes (which is about 1.3 million people globally). That’s not all tailpipe pollution. Brake linings and rubber tires wear out. Where do those particulates go? Your lungs. The water supply. All sorts of places they shouldn’t. And the better we make transport systems for people using cars, the worse it is for everyone else. For instance, traffic signal timings benefit cars at the expense of pedestrians in many cities. I’d also add police stops in the US in the name of safety are mostly unnecessary, lead to excessive deaths, and could be replaced with photo radar and similar systems.

Micro Reads

🚜 Deere Rolls Out Fully Autonomous Tractor at CES - John McCormick, WSJ | This seem like an obvious use of AV technology, even more than long-haul trucking. One analyst quoted in the piece compared the move from conventional tractors to autonomous tractors to the shift from horses to the combustion engine. The productivity impact? “The machines should be able to work around the clock, allowing for more efficient use of labor; better application of seeding, fertilizer and other inputs; and lead to higher yields and lower ecological impact,” according to one analyst.

🐂Wall Street Loves China More Than Ever - Cathy Chan and David Scanlan, Bloomberg | It’s pretty tough to run a New Cold War with China if neither Wall Street nor Silicon Valley wish to participate.

Some U.S. politicians have been calling for companies to back away from China, over concerns about national security and human rights. But Wall Street banks are instead deepening their ties. JPMorgan in August took full control of a securities joint venture with a Chinese company, and now wants to do the same with an asset management business it partly owns. Morgan Stanley is seeking five new banking licenses in mainland China in 2022, while Goldman Sachs has been doubling its workforce. Citigroup applied in December for a securities trading and investment banking permit and plans to seek a futures license in 2022, adding 100 employees in the country in all.

😴 Europe Sleepwalked Into an Energy Crisis That Could Last Years - Bloomberg Green | “Although the situation came to a head abruptly, it’s been years in the making. Europe is in the midst of an energy transition, shutting down coal-fired electricity plants and increasing its reliance on renewables. Wind and solar are cleaner but sometimes fickle, as illustrated by the sudden drop in turbine-generated power the continent recorded last year.”

🌈 A green ray of hope in surging tech investment - Editorial Board, FT | Tech breakthroughs and innovations, big and small, are hardly the distraction that some environmentalists paint them to be. We going to need lots of them. “According to PwC’s recent State of Climate Tech report, some 6,000 investors, ranging from venture capital and private equity firms to government funds and philanthropists, have backed more than 3,000 climate tech start-ups since 2013. In total, investors have sunk about $222bn into these start-ups. Funding has increased 210 per cent over the past year.”

I had been following the Futures exhibit, excited to see something like that at the Smithsonian. Very disappointed to hear how it turned out.

Who are they hiring for curators?