🎬 Why 2022 won't be anything like the 2022 of 'Soylent Green'

Also: a hypersonic missile race, what's next for SpaceX, rising automation, and more ...

“The world has been oscillating between fears of two catastrophes — the population explosion and the atom bomb. Both pose a mortal threat. In this intolerable situation, with the menace of doomsday hanging over us, Dr. Borlaug comes onto the stage and cuts the Gordian knot. He has given us a well-founded hope, an alternative of peace and of life — the green revolution.” - Nobel presentation speech given in honor of agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug when he was awarded the 1970 Peace Prize.

🎄 Note to my wonderful Faster, Please! subscribers: This newsletter will be modified, both in format and publishing schedule, between now and year’s end. Have a wonderful holiday season! And please tell your family, friends, and colleagues — even randos on the street — to check out Faster, Please and subscribe!

Short Read

🔮 Why 2022 won't be anything like the 2022 of “Soylent Green”

Recall the tagline in Apple’s famous “1984” commercial — the one that opens with the javelin thrower pursued by stormtroopers — introducing its new Macintosh computer: “. . . you'll see why 1984 won't be like ‘1984.’” It was the perfect match of savvy marketing with a significant moment. We had arrived at the year that supplies the title of George Orwell’s vision of a totalitarian nightmare world, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

We’ve now arrived at another key moment in the timeline of dystopian science fiction. In two days, it will be 2022, the year that provides the then-futuristic setting for Soylent Green. (Next up: Children of Men in 2027.) Watching the 1973 film is like opening a cinematic time capsule filled with the era’s post-Silent Spring ecological anxieties. It’s all there: Overpopulation, hunger, global warming and oppressive humidity, stark inequality, depleted natural resources, widespread euthanasia — not to mention a solid performance by Charlton Heston as our laconic guide through this hellscape of sticky squalor. Unlike Nineteen Eighty-Four, however, Soylent Green is clearly meant as a warning about the miserable shape of things to come. In the 2018 essay “Malthus at the Movies: Science, Cinema, and Activism around Z.P.G. and Soylent Green,” Jesse Olszynko-Gryn and Patrick Ellis write that Heston was concerned about overpopulation and used his star power to get Soylent Green made. The script was loosely based on Make Room! Make Room!, a 1966 science fiction novel by Harry Harrison that had quickly come and gone:

Heston was particularly concerned with overpopulation, a then bipartisan issue supported not only by leftwing environmentalists, but also by Republican conservationists and conservative anti-immigration activists. According to his biographer, Soylent Green was “the only film that Heston made with the express purpose of advancing a political message. . . . Heston was able to push Harrison’s novel through the studio system, but only after the commercial success of Skyjacked, in which he starred. Initially, he and producer Walter Seltzer invested their own money to have a screenplay written, but MGM was “wary of tackling [. . .] over-population — no doubt for fear of stepping on religious toes.”

So why isn’t 2022 for us going to be anything like the 2022 of Soylent Green? Well, the pessimists back then got a lot wrong.

They failed to grasp the “demographic transition” when people in rich countries start having fewer kids. The average fertility rate in at least moderately rich countries is now just 1.6, well below replacement. Today’s population-related anxiety is about too few of us, not too many. Oh, and the Big Apple is less than a quarter of the size predicted in the above image from the film’s opening.

The Green Revolution — the creation of high-yielding crop varieties and new agronomic techniques — caused a huge increase in agricultural productivity. No need for the film’s eponymous foodstuff.

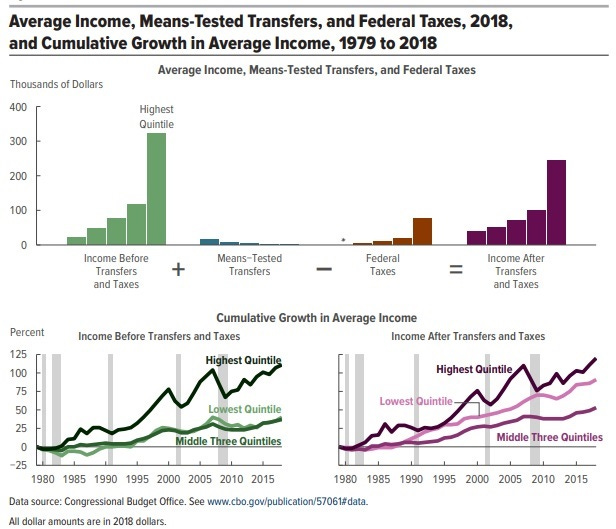

A turn toward market economics led to huge drops in poverty and hunger in Asia, especially in China and India, which also reduced global inequality. And while US income inequality is greater today than in the 1970s, all income groups are better off today than back then:

Finally, as always, the ingenuity that democratic capitalism allows and enables meant we learned to do more with less. When the price of resources rises, we search harder for more of that resource and for substitutes. Tomorrow is rarely like today thanks to invention and innovation. For example: The notion of Peak Oil became a punchline thanks to the Shale Revolution. Another example: the Julian Simon-Paul Ehrlich wager of 1980 over resource scarcity, won by the former when the prices of copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten all declined over the subsequent decade. And in the excellent More from Less, Andrew McAfee cites research finding a “dematerialization” of the American economy since the early 1970s with a decline in the absolute consumption of key commodities such as steel, copper, fertilizer, timber, and paper. “Total annual US consumption of all of these had been increasing rapidly in the years prior to Earth Day.” As McAfee explains:

We invented the computer, the Internet, and a suite of other digital technologies that let us dematerialize our consumption: over time they allowed us to consume more and more while taking less and less from the planet. This happened because digital technologies offered the cost savings that come from substituting bits for atoms, and the intense cost pressures of capitalism caused companies to accept this offer over and over. Think, for example, how many devices have been replaced by your smartphone.

Of course, we have more to do. Still too many poor people and hungry people. Still too many of us unable to more fully realize our human potential. But looking at why 2022 isn’t 2022 should give us some hints at how to better create a better future.

And if you’re interested in what humanity does right when it makes progress — and what it does wrong when it doesn’t — please check out some of my AEI Political Economy podcasts. They all include links to full transcripts:

Azeem Azhar: The age of exponential technology

Jason Crawford: Lessons from studying the roots of progress

Johan Norberg: The history and psychology of progress

Philip Coggan: How did the world get so rich?

Ronald Bailey: Global trends every smart person should know

Andrew McAfee: Capitalism, tech progress, and the environment

Micro Reads

⚠ Mach 5 Missiles Spur New Arms Race as U.S. Seeks to Match China - Ryan Beene, Bloomberg | While the technology seems to be there — or at least progressing along the right track — there are plenty of questions about how exactly these weapons would alter the military balance and the odds of conflict among the countries that have them. I also have no idea what this quote from a Raytheon executive is supposed to mean: “Hypersonic technology is the natural evolution on the path to where we’ll eventually go, which is to speed-of-light weapons.” I’m sorry, what now?

🧪 A massive 8-year effort finds that much cancer research can’t be replicated - Tara Haelle, ScienceNews | Another replication crisis story — this time in cancer research. Researchers were only able to replicate a quarter of the 193 experiments they aimed to reproduce, the piece reports. But flaws in the original studies weren't the only obstacles to replication. A paucity of details about methods meant that replication was dependent on collaboration with the original researchers, some of whom were not cooperative. "Ultimately, if science is to be a self-correcting discipline, there needs to be plenty of opportunities not only for making mistakes but also for discovering those mistakes, including by replicating experiments, the project’s researchers say."

🚀 SpaceX’s Future Depends on a Gigantic Rocket and 42,000 Internet Satellites - Micah Maidenberg, WSJ | A good explainer, including lots of financial numbers, of the SpaceX strategy going forward, including the importance of the Starship rocket for the Starlink satellite business.

Starship also forms an important foundation of the future business strategy at his space company, which wants to use the vehicle in part to build out Starlink, the satellite-internet service many investors believe could eventually form the bulk of the company’s revenue. . . . Starship, which would be blasted to orbit on a booster dubbed Super Heavy, stands 160 feet tall and has a diameter of 30 feet, creating room to send hundreds of Starlink satellites to orbit at once, more than the several dozen it is able to deploy right now on one of its Falcon 9 rockets.

💻 Tech That Will Change Your Life in 2022 - Joanna Stern, Nicole Nguyen, and Christopher Mims, WSJ | Here’s some of what might be happening over the coming year:

By the end of 2022, U.S. car buyers could have more than 100 different models to choose from. And many forthcoming models will be more affordable than what was available just a year or two ago. . . . Not coming in 2022: The all-helpful home robot who will take care of the kids, do the dishes and unclog the toilet. Coming in 2022: Home robots that can do more than your stationary smart speaker or roving vac—and might even keep us company. . . . Meta (formerly Facebook) plans to release a headset more advanced and expensive than its current Quest 2. It won’t be a one-horse metaverse race. There are reports of a late 2022 release of an Apple mixed-reality headset. . . . Next year, U.S. carriers are sunsetting their aging third-generation cellular networks to make more room for the superfast fifth generation, 5G. The telecoms have plans to expand their networks in the coming year. T-Mobile said it would reach 50 million more Americans by year-end. . . . So you’ve been getting by, nodding along when people talk about cryptocurrency and NFTs, thinking all chatter about the decentralized web and blockchains will pass by like a cheetah on an e-bike. It won’t. Sorry. In fact, in 2022, you might even get in yourself as tools to buy, sell and send digital money and tokens appear in the apps, services and games you already use.

🤖 The robot work force isn’t coming. It’s already here - Melissa Repko, CNBC | A great round-up of various automation efforts by US companies, partly accelerated by the pandemic. “Walgreens is turning to automation to fill prescriptions, while Sprinkles and Starbucks move to swap out cashiers for tablets. Elsewhere, Walmart-owned Sam’s Club is using robots to scrub store floors and scan inventory at some locations, and restaurant chains like Buffalo Wild Wings and White Castle are testing robots that can flip burgers or make chicken wings.”

🔮 Do Well Managed Firms Make Better Forecasts? - Nicholas Bloom, Takafumi Kawakubo, Charlotte Meng, Paul Mizen, Rebecca Riley, Tatsuro Senga, and John Van Reenen, NBER | Predictions are difficult, especially about the future. That said, firms with higher management scores in areas such as productivity and profitability and size are “significantly more accurate in their forecasts about macroeconomic growth (GDP) and their own growth” over the subsequent year. This suggests that “one reason for the superior performance of better managed firms is that they knowingly make more accurate forecasts, enabling them to make superior operational and strategic choices.”

The reason all those commodities were used less in the USA over the past 50+ years is that our industrial capacity was destroyed and moved to other countries. We're consuming, not creating. We're living off of our rapidly depleting capital, in both material wealth and experience/knowledge bases. That's left us a poorer and less independent nation and made us vulnerable to destruction. Of course, that was the purpose of it, but we can't say that now, can we?

href=”https://fasterplease.substack.com/”>Phone</a>