🤖 The story of MLK and 1960s concerns about automation

Back then, worries about 'cybernation' were common even as joblessness was declining

To some, it may be surprising that in his final sermon — delivered on March 31, 1968, from the Canterbury Pulpit at Washington National Cathedral — Martin Luther King Jr. mentioned technological change. From that sermon, “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution”:

There can be no gainsaying of the fact that the great revolution is taking place in the world today. In the sense it is a triple revolution: that is, a technological revolution with the impact of automation and cybernation; then there is a revolution in weaponry with the emergence of atomic and nuclear weapons of warfare; then there is the human rights revolution with the freedom explosion that is taking place all over the world.

Similarly in his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, MLk also wrote on the subject of technology and human progress. After beautifully outlining how the “world of today is vastly different from the world of just one hundred years ago” in terms of tech progress, he vividly looked forward:

The years ahead will see a continuation of the same dramatic developments. Physical science will carve new highways through the stratosphere. In a few years astronauts and cosmonauts will probably walk comfortably across the uncertain pathways of the moon. In two or three years it will be possible, because of the new supersonic jets, to fly from New York to London in two and one-half hours. In the where do we go from here years ahead medical science will greatly prolong the lives of men by finding a cure for cancer and deadly heart ailments. Automation and cybernation will make it possible for working people to have undreamed-of amounts of leisure time. All this is a dazzling picture of the furniture, the workshop, the spacious rooms, the new decorations and the architectural pattern of the large world house in which we are living.

Great, great stuff there. Throughout the short history of this newsletter, I’ve tried to convey the tremendous Up Wing future-optimism that pervaded American society before the onset of the Great Downshift — starting 50 years ago in 1973 — in productivity-driven economic growth. Back then, many of us believed the whole kit-and-kaboodle was almost surely on its way: Cures to cancer and other chronic diseases, a booming orbital economy and space colonies, limitless energy, and, yes, skies thick with flying cars zooming about. Confidence in the potential of scientists, technologists, and entrepreneurs to deliver a wondrous tomorrow ran stratospherically high.

But that dream came with two significant caveats, nicely expressed by Herman Kahn, the Cold War nuclear conflict theorist turned futurist who’s the de facto patron saint of Faster, Please! Asked in 1976 if the gloomy future of scarcity being promoted by many environmentalists could be avoided, Kahn replied, “Absolutely, given only two caveats: We don’t have disastrously bad luck and that we don’t do things that are incredibly dumb. It takes a moderate but not extraordinarily good level of decision-making to overcome the problems we can imagine in the future.”

First, we had to avoid the bad luck of global thermonuclear war. (The number of close calls from the late 1959s through early 1980 is breathtaking.) My growing awareness of the depth of postwar optimism makes the final scene — HISTORIC CINEMATIC SPOILER COMING UP!!! — of the 1968 film Planet of the Apes really hit differently.

When astronaut Charles Taylor (Charlton Heston) realizes he’s been marooned in the future of a nuclear-war shattered Earth rather than on a distant planet 300 light years away, he falls to his knees and lets out with a primal cry: “Oh, my God. I'm back. I'm home. All the time, it was … we finally really did it. You maniacs! You blew it all up! Damn you! God damn you all to hell!” And while I used to view this scene as purely a lament about the loss of a civilization as it was, I now see it equally as a lament for the loss of a future civilization — a wealthier, more capable, and, hopefully, kinder one — that never came to be.

The other Kahn caveat is that we needed to make decent decisions. Policymaking matters. That has gone less well over the decades (although one could argue that avoiding nuclear is a policy success that dwarfs all others), as I have also spent time discussing in this newsletter. It seems that the good decisions, including the consumer welfare standard for anti-trust and light internet regulation, were more than offset by the many bad ones, especially in the areas of environmental regulation and federal research spending.

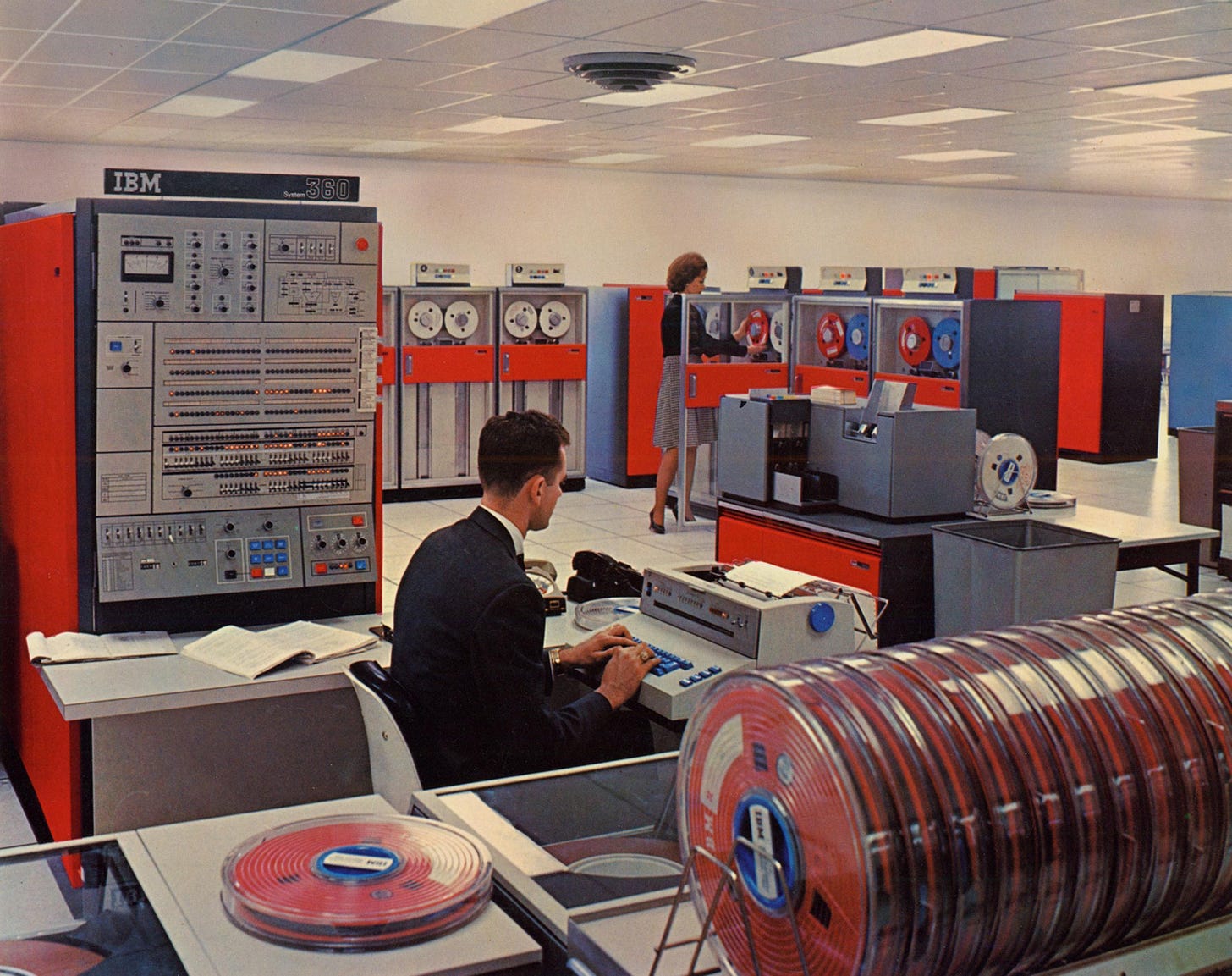

The notion that policy has some role to play in shaping our technologically dynamic economy, present, and future, was hardly limited to forward thinkers like Kahn. Although many economists at the end of World War II were deeply worried about a return to prewar tumult — high unemployment and economic depression/stagnation — the postwar boom had by the early 1960s created a different set of concerns centered around rapid technological progress and economic growth. Chief among these concerns were fears about automation:

This from the Feb, 24, 1961 issue of Time magazine:

The rise in unemployment has raised some new alarms around an old scare word: automation. How much has the rapid spread of technological change contributed to the current high of 5,400,000 out of work? The number of jobs lost to more efficient machines is only part of the problem. What worries many job experts more is that automation may prevent the economy from creating enough new jobs. Says Pennsylvania's Democratic Congressman Elmer J. Holland, whose subcommittee is about to study the matter: "One of the greatest problems with automation is not the worker who is fired, but the worker who is not hired." Throughout industry, the trend has been to bigger production with a smaller work force.

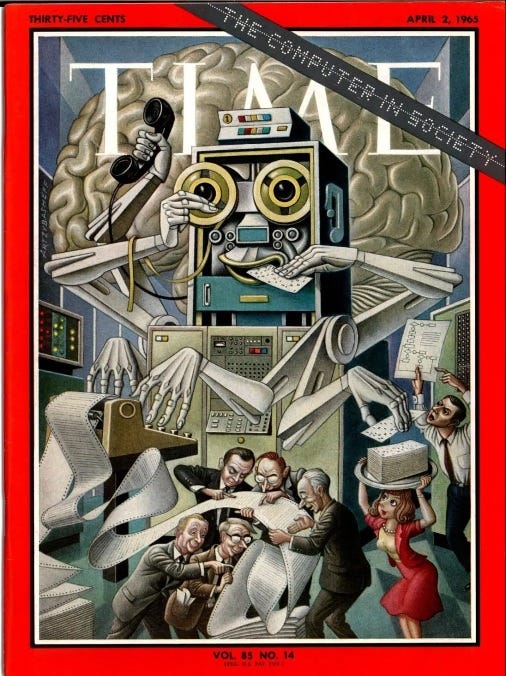

Time returned to the issue of computers and society with a lengthy cover story on April 2, 1965 (from which the above cover image is taken), one expressing similar automation concerns:

At least for now, the computer seems to raise almost as many problems as it solves. The most pressing and practical one is, of course, displacement of the work force. Each week, the Government estimates, some 35,000 U.S. workers lose or change their jobs because of the advance of automation. There are also thousands more who, except for automation, would have been hired for such jobs. If U.S. industry were to automate its factories to the extent that is now possible—not to speak of the new possibilities opening up each year—millions of jobs would be eliminated. Obviously, American society will have to undergo some major economic and social changes if those displaced by machines are to lead productive lives.

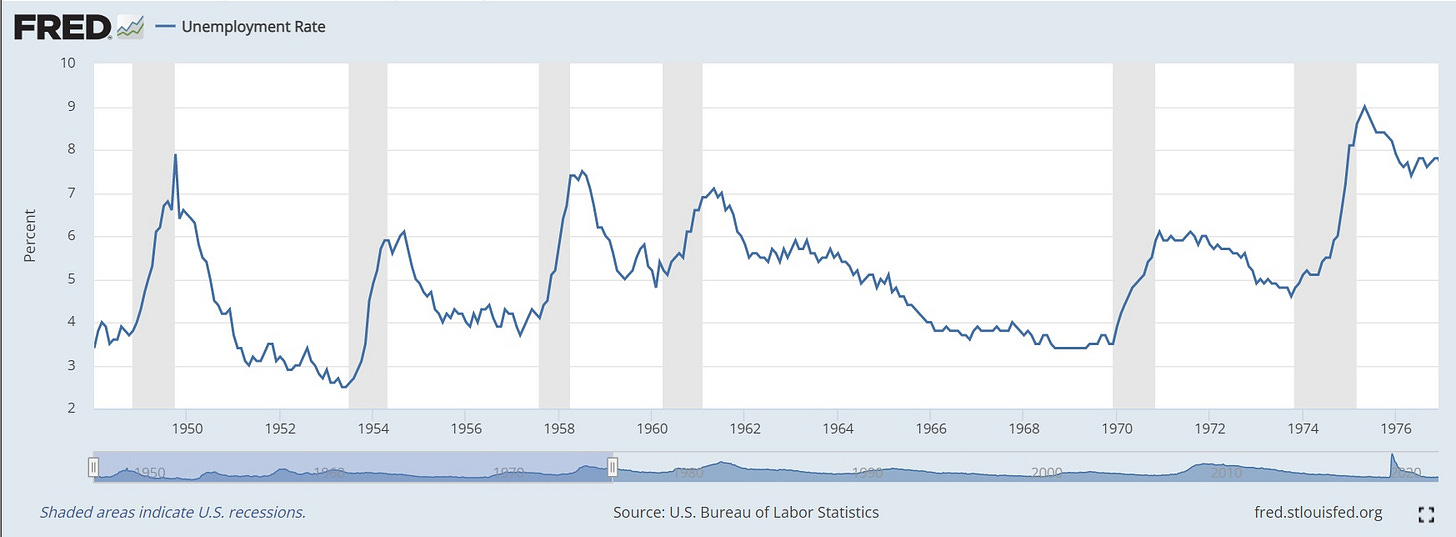

Concerns about technological unemployment were not limited to America’s most influential news magazine. As the above comment by Rep. Holland suggests, the automation issue was on Washington’s radar as well. On August 19, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed a bill creating the National Commission on Technology, Automation, and Economic Progress. What’s interesting here is how the intervening years of economic growth probably changed Washington’s perspective on the issue from the early 1960s to the middle 1960s. When Holland was quoted in Time, the U.S. was experiencing its third recession since the early 1950s, and the unemployment rate was nearly 7 percent versus a post-war low of 3.7 percent in 1957.

Yet even as Holland was giving that quote, the economy was shifting to recovery mode. By the time LBJ signed that commission into law, the jobless rate had fallen to 5 percent, and the U.S. economy was well into a boom where economic growth averaged 4.3 percent over the decade with unemployment falling to a postwar low of 3.4 percent in 1968. In his 1964 remarks on the commission, LBJ didn’t seem all that worried about technological unemployment as long as government planned for the inevitable disruption it would cause:

Automation is not our enemy. Our enemies are ignorance, indifference, and inertia. Automation can be the ally of our prosperity if we will just look ahead, if we will understand what is to come, and if we will set our course wisely after proper planning for the future. … The techniques of automation are already permitting us to do many things that we simply could not do otherwise. Some of our largest industries, some of our largest employers would not exist and could not operate without automation, and some of those employers are here this morning. … We could not provide our great shield for the security of this country and the shield for the security of the free world if we did not have automation in the United States. If we understand it, if we plan for it, if we apply it well, automation will not be a job destroyer or a family displaced. Instead, it can remove dullness from the work of man and provide him with more than man has ever had before.

Not everyone at the time expressed as rosy a view as LBJ and the New Frontier/Great Society Democrats. Earlier that year, the left-wing Ad Hoc Committee on the Triple Revolution sent the president a letter “in the recognition that mankind is at a historic conjuncture which demands a fundamental reexamination of existing values and institutions.” The group highlighted “three separate and mutually reinforcing revolutions” taking place in America and the world at the time: the Weaponry Revolution, the Human Rights Revolution, and the revolution most relevant to this newsletter, the Cybernation Revolution:

A new era of production has begun. Its principles of organization are as different from those of the industrial era as those of the industrial era were different from the agricultural. The cybernation revolution has been brought about by the combination of the computer and the automated self-regulating machine. This results in a system of almost unlimited productive capacity which requires progressively less human labor. Cybernation is already reorganizing the economic and social system to meet its own needs.

The Ad Hoc Committee saw the Cybernation saw the problem of creating abundance as solved. Now was the time to focus on the redistribution of that abundance. It saw a highly productive economy whose fruits were not being widely spread: “The underlying cause of excessive unemployment is the fact that the capability of machines is rising more rapidly than the capacity of many human beings to keep pace. A permanent impoverished and jobless class is established in the midst of potential abundance.”

To deal with the Cybernation Revolution, the Ad Hoc Committee recommended federal actions far beyond those that eventually formed the basis of LBJ’s Great Society, including a guaranteed income, a massive public works program, an excess profits tax on corporations, and government restraint on tech progress. On that final point, specifically, the Ad Hoc Committee called for the “use of the licensing power of government to regulate the speed and direction of cybernation to minimize hardship.”

While MLK was not a signee to the Ad Hoc Committee’s statement (or a member), he was philosophically in tune with it (as his sermon shows), including support for a universal basic income. Similarly, King saw technology continuing at the rapid postwar pace. And his speculation about expanded leisure time, echoed the famous 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” by John Maynard Keynes.

A few additional thoughts:

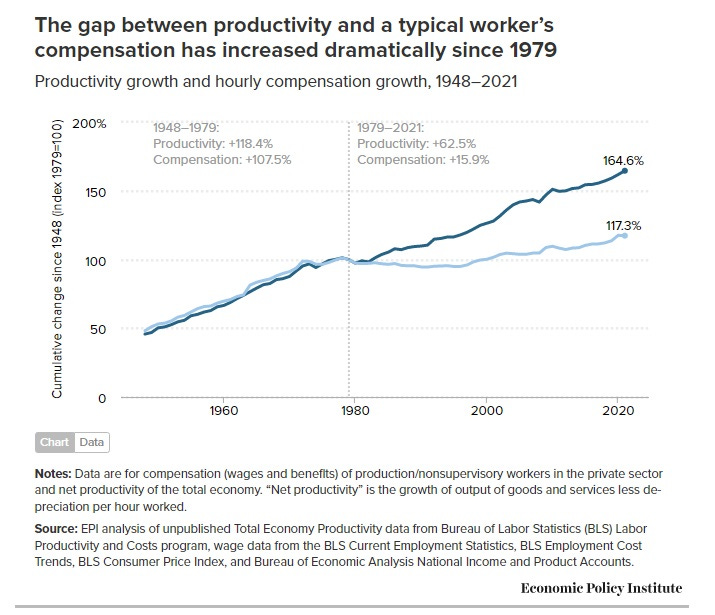

First, the economics of the tech worriers was dodgy. Almost by any measure, productivity and pay during the period were tightly linked, as seen in this chart from the Economic Policy Institute (which is unduly negative about the long-run relationship between the two):

Second, along the same lines, 1960s concerns about technological unemployment were happening at the very same time a fast-growing economy was grinding down joblessness to levels not seen again until the 1990s tech boom and then just before the Great Pandemic (indeed, the pre-pandemic period was beset with concerns that robots were on the verge of taking all the jobs) and again now.

Third, progress enthusiasts should never assume the results speak for themselves. Indeed, it seems more progress means more concerns. Up Wing tech-solutionists must constantly make the public case as to why faster growth is good, more is better, and, when warranted, why critics are offering misguided and mistaken arguments.

Fourth, I would love to return to a period where our biggest concerns were about potential downsides of abundance and how to minimize them rather than dealing with sustained slow growth and the politics of scarcity.

Micro Reads

▶ We’ve Made Huge Progress on Cancer. Let’s Protect It. - Lisa Jarvis, Bloomberg Opinion | The US has made substantial progress in in the battle against cancer, cutting the number of deaths from the disease by 33% since 1991. According to a new analysis from the American Cancer Society, that’s 3.8 million cancer deaths averted. People are living longer with cancer, too. The 5-year survival rate across all kinds of cancers has increased from 49% in the mid-1970s to 68% for someone diagnosed between 2012 and 2018. … Over the last few decades, many cancers have been caught early enough or prevented altogether thanks to a combination of screening, lifestyle changes (most prominently, the downward trend in smoking) and vaccination.

▶ What the end of the US shale revolution would mean for the world - Derek Brower and Myles McCormick, Financial Times | The golden age of shale “vaulted the United States back to the top of the table in terms of geopolitical significance”, says David Goldwyn, a former senior energy adviser to Barack Obama and head of Goldwyn Global Strategies, a Washington consultancy. “The US is no longer in a position where it has to worry about the physical supply of oil or gas . . . and that gives it a great deal more freedom of action in international affairs.” Additionally, the cumulative abundance of shale supply delivered over the past 15 years continues to shelter Americans from the sky-high natural gas and fuel prices that have rattled other developed economies, giving its industry a competitive advantage and its households more disposable income. … But that transformative age is drawing to a close, say analysts, with unpredictable consequences. High costs and labour shortages now bedevil the shale patch. Wall Street wants profits paid back to investors, not reinvested in new rigs. Even with crude prices at $80 a barrel, a price far above the long-term average, shale producers still fear to splurge capital. To top it off, new wells are yielding less oil. “The aggressive growth era of US shale is over,” says Scott Sheffield, chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, the country’s biggest shale producer. “The shale model definitely is no longer a swing producer.”

▶ A fountain of youth for dogs? This S.F. startup says it’s on the way - Carolyn Said, San Francisco Chronicle |

▶ America’s trustbusters plan to curtail the use of non-compete clauses. Good - The Economist |

▶ How Finland Is Teaching a Generation to Spot Misinformation - Jenny Gross, The New York Times | While teachers in Finland are required to teach media literacy, they have significant discretion over how to carry out lessons. Mrs. Martikka, the middle school teacher, said she tasked students with editing their own videos and photos to see how easy it was to manipulate information. A teacher in Helsinki, Anna Airas, said she and her students searched words like “vaccination” and discussed how search algorithms worked and why the first results might not always be the most reliable. Other teachers also said that in recent months, during the war in Ukraine, they had used Russian news sites and memes as the basis for a discussion about the effects of state-sponsored propaganda.

▶ How technology is redrawing the boundaries of the firm - The Economist | In the rich world, fast broadband and apps like Zoom or Microsoft Teams are allowing a third of working days to be done remotely. Jobs are trickling out from big-city corporate headquarters to smaller towns and the boondocks. And the line between collaborating with a colleague, a freelance worker or another firm is blurring. Companies are drawing on common pools of resources, from cloud computing to human capital. By one estimate, skilled freelance workers in America earned $247bn in 2021, up from about $135bn in 2018. The biggest firms in America and Europe are outsourcing more white-collar work. Exports of commercial services from six large emerging markets have grown by 16.5% a year since the pandemic began, up from 6.5% before it (see chart 1). On January 9th Tata Consultancy Services (tcs), an Indian it-outsourcing giant, reported another bump in profits.

▶ The Spectacular Promise of Artificial Intelligence - Robert Tracinski, Discourse |

▶ Deep brain stimulation could reduce emotional impact of memories - Jason Arunn Murugesu, NewScientist |

▶ NASA’s return to the Moon is off to a rocky start - Rebecca Boyle, MIT Tech Review |

▶ Microsoft’s $10bn bet on ChatGPT developer marks new era of AI - Richard Watters and Tabby Kinder, Financial Times | Google and other tech giants, as well as a number of start-ups, have also ploughed resources into creating giant AI models like this. But since GPT3 stunned the AI world in 2020 with its ability to produce large blocks of text on demand, OpenAI has set the pace with a succession of eye-catching public demonstrations. Microsoft executives are looking to use the technology in a wide range of products. Speaking at a company event late last year, chief executive Satya Nadella predicted that generative AI would lead to “a world where everyone, no matter their profession” would be able to get support from the technology “for everything they do”. Generative AI is set to become a central part of “productivity” applications like Microsoft’s Office, said Oren Etzioni, an adviser and board member at A12, the AI research institute set up by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. All workers will eventually use productivity software that presents relevant information to them, checks their work and offers to generate content automatically, he said. The potential upheaval this could cause in the software world has not been lost on Microsoft’s rivals, who see the technology as a rare opportunity to break into markets dominated by Big Tech.