🙃 The strange plunge in US productivity growth, explained

Scary statistics are more the result fuzzy pandemic-era data than a collapse in something fundamental to American prosperity

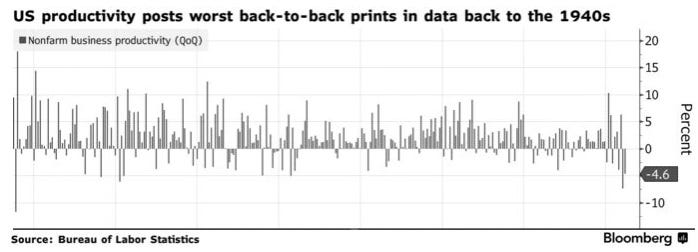

Item: US productivity slumped for a second-straight quarter as the economy shrank, driving another surge in labor costs that risks keeping inflation elevated and further complicates the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame price increases. Productivity, or nonfarm business employee output per hour, decreased at a 4.6% annual rate in the second quarter after falling at a 7.4% pace in the previous three months, Labor Department figures showed Tuesday. That marked the weakest back-to-back readings in data back to 1947. On a year-over-year basis, output per hour fell by the most on record. It will likely take some time to establish the underlying trend in productivity in the wake of the pandemic, but if it has permanently downshifted, there could be lasting repercussions for the well-being of the economy in the long run. - Bloomberg, 08/09/2022

I started this newsletter because I looked around at the panoply of early 21st century scientific leaps and technological advances and got pretty excited. AI/machine learning, CRISPR, reusable rockets, robotics, nuclear fusion(!) and advanced geothermal energy. Maybe what the Great Stagnation — the downshift in postwar economic productivity growth apart from the boomy late 1990s and early 2000s — was coming to an end. Next up: a New Roaring Twenties, Thrilling Thirties, Fantastic Forties, and beyond. Maybe even urban skies finally dotted with flying cars.

Given such a historic host emerging innovations, I thought it important to highlight and argue for public policies that would encourage more breakthroughs — and the successful commercialization of the ones that have already happened. A pro-progress “Up Wing” culture would be helpful, too. Too many false starts over the past half century to ignore the need for a supportive policy and cultural ecosystem. Got to avoid “technology traps” and dead ends if we want to invent a better world.

I’m mean, I’m not not worried about the productivity plunge

That said, how nervous am I about these terrible productivity numbers? Well, certainly not zero nervous. Productivity growth is crucial to economic progress and rising living standards. I won’t totally handwave away these numbers, even though productivity growth rates can be extremely volatile and subject to big revisions.

Throughout the pandemic, I’ve thought considerably about the Down Wing bear case for productivity growth. What if the outbreak causes, as Bloomberg speculates, another downshift? The outbreak seems to have broken our brains in many cases, so why not the economy, too? Maybe as a society we become more risk averse? Maybe WFH is bad for productivity longer-term. Maybe we become more “drawbridge” up in regards to immigration and trade.

Or more basically: The pandemic and shutdown were huge, disruptive shocks to businesses and their workers and “the early read is that the growth potential of the economy is weaker than it was pre-COVID,” says Brian Wesbury, chief economist at First Trust. (Also recall the pro-productivity pandemic case, which I outline here.)

Then again, productivity numbers are notoriously jumpy. And that might be doubly the case during a once-in-a-century pandemic that seems to keep generating odd economic numbers like shrinking GDP with strong job creation. Look at the inflation surge: What’s causing it? Demand shocks? Supply shocks? A combo? How to assign causality, exactly? Good luck with that.

Here’s what we think we know or can reasonably speculate

So what is probably happening with these wacky productivity numbers? I feel modestly confident presenting two cautious insights — one reassuring, the other somewhat less so. Let’s begin with optimism: There’s probably is a mismeasurement problem happening here. I mean, almost certainly that’s a significant factor. As a research note from Capital Economics puts it:

It is difficult to find an explanation for why productivity has deteriorated so rapidly … The drop in productivity is most likely a statistical mirage. … The 2.5% slump in productivity over the past year – the worst since records began in 1948 – is another illustration of the chasm that has opened up between the GDP and employment figures. The only plausible explanation to our minds is that one or both of those series will be revised over the coming months, leaving productivity growth stronger and unit labor cost growth weaker. … Revisions to both the employment and national accounts data have the potential to markedly change the recent productivity figures. Based on the GDI figures, labour productivity of the non-financial corporate sector was 6.8% above pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter, as opposed to only 2.6% higher on the GDP-based numbers. The upshot is that we’re not sweating too much over the weak productivity figures when the current collapse may eventually be revised to only a small blip.

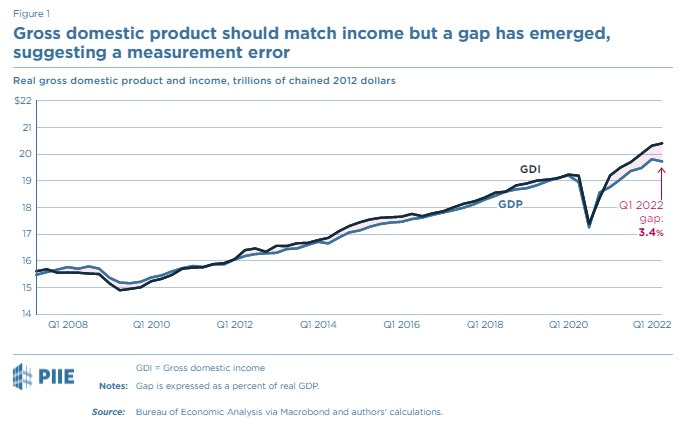

Speaking of “chasm,” there has been a big one between GDP, gross domestic product, and GDI, gross domestic income. In fact, the largest chasm ever when in theory they should be identical. Sometimes economists will average the two when there is a gap to find the most accurate measure of growth. If you do this GDP-GDI averaging over the first two quarters, the resulting productivity — output per hour — looks a bit better.

This from Jason Furman and Wilson Powell at the Peterson Institute for International Economics:

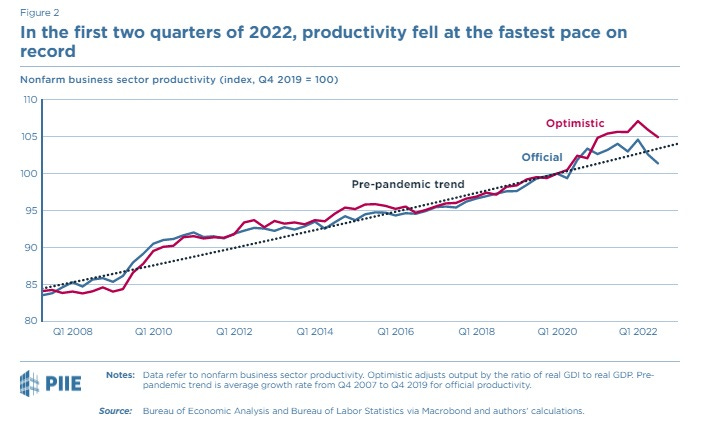

Our “optimistic” case adjusts the BLS estimate of real value-added output in the nonfarm business sector by the ratio of real GDI to real GDP. For the second quarter of 2022, we assume that real GDI growth was zero, which is more optimistic than the -0.9 percent decline in real GDP, in part reflecting some anomalies in the GDP data, which suggest GDP might have understated economic growth again in the second quarter. … By both measures, productivity fell over the last two quarters. The official BLS measure fell at a 6.0 percent annual rate, nearly twice the previous record for the worst two quarters since the data started in 1947. The optimistic measure fell at a 4.0 percent annual rate, which would also be a record two-quarter decline. The fact that productivity declined—or grew at a very slow rate—is robust.

But again, it’s important to look at productivity numbers over longer periods, such as the entire pandemic cycle to date. Again, Furman and Powell:

Over the entire pandemic period it appears that productivity growth has been slower than it was in the previous business cycle, although this is less certain. The official BLS series for productivity rose at a 0.6 percent annual rate since the fourth quarter of 2019, well below the 1.3 percent annual rate in the peak-to-peak of the previous business cycle or the 1.7 percent annual rate in the two years leading up to the pandemic. The optimistic case shows productivity above the pace of the last business cycle and even above the pace immediately preceding the pandemic.

Don’t day trade productivity numbers. Think longer term.

Kind of good news — or at least OK news — I guess. Again, let’s see how the data shakes out. It’s certainly a red flag, or maybe a reassuring green flag in this case, that the broad statistical collapse in productivity “has not been mirrored in the manufacturing sector, where the data are largely independent on the national accounts,” notes Capital Econ. Productivity in manufacturing increased by 5.5 percent in the second quarter and is up by 0.4 percent over the past year.

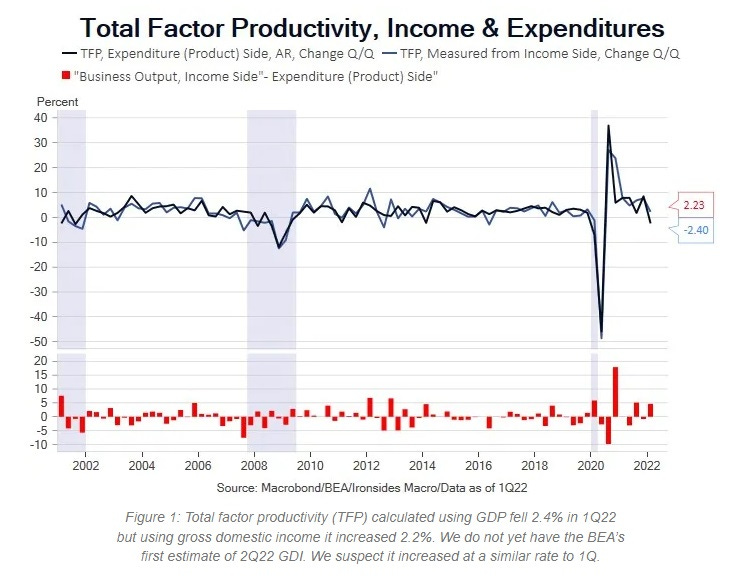

Let also add this optimistic insight from Barry Knapp of Ironsides Macroeconomics:

We do not have the BEA’s first GDI estimate, however employee compensation increased 10% in 2Q, down from 11.1% in 1Q. It seems likely the corporate sector net operating surplus was at least as strong as Q1’s 8.4% increase, given a 10% increase in Russell 3000 earnings, the drag on those earnings from companies with large international sales (not counted in gross domestic income), rising sales per employee, and near record profit margins. … [We] expect that nominal gross domestic income grew roughly 10% in 2Q, consequently, real GDI was likely positive, implying that total factor productivity calculated using the income method was also positive.

I would love to see that. Remember, total factor productivity is that part of labor productivity that represents technological and business innovation. Over the past century, TFP gains have accounted for well over half the growth in measured U.S. labor productivity versus the growth of inputs to production, such as the number of hours worked or the amount of capital used. TFP is key to future productivity growth and economic prosperity.

Less good, however, is this: I recently wrote about the short-lived 2020 productivity boom, which doesn’t seem to have been caused by “automation, artificial intelligence, and a massive investment by households in the equipment and software needed to conduct work from home,” observe economists Robert J. Gordon (Northwestern University) and Hassan Sayed (Princeton University) in their new NBER working paper, “A New Interpretation of Productivity Growth Dynamics in the Pre-Pandemic and Pandemic Era U.S. Economy, 1950-2022. So not a tech progress thing.

They continue: “Positive pandemic-era productivity growth can be entirely explained by a surge in the performance of work-from-home service industries, while goods industries soared and then slumped, while contact services recorded strongly negative productivity growth throughout 2020-22.”

I mean, I’ll take productivity growth where I can find it, but what we need is technological progress with sustained economy-wide impacts. A general purpose technology such as, for instance, AI. WFH isn’t it. Which brings us back to the beginning. No time to panic or worry, only time to work hard at creating that better world I referred to earlier. Faster, please!

Micro Reads

▶ Congress Just Passed a Big Climate Bill. No, Not That One - Robinson Meyer, The Atlantic | The CHIPS bill’s programs focus on the bleeding edge of the decarbonization problem, investing money in technology that should lower emissions in the 2030s and beyond. … TThe law, for instance, establishes a new $20 billion Directorate for Technology, which will specialize in pushing new technologies from the prototype stage into the mass market … Although the directorate will focus on broad improvements across technology, such as AI and high-performance computing, two of the directorate’s 10 new focus areas are climate or clean-energy related. Congress has explicitly tasked the new office with studying “natural and anthropogenic disaster prevention or mitigation” as well as “advanced energy and industrial efficiency technologies,” including next-generation nuclear reactors. … The bill also directs about $12 billion in new research, development, and demonstration funding to the Department of Energy, according to RMI’s estimate. That includes doubling the budget for ARPA-E, the department’s advanced-energy-projects skunk works. … And it allocates billions to upgrade facilities at the government’s in-house defense and energy research institutes, including the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, and Berkeley Lab, which conducts environmental-science research.

▶ Biden wants minerals, but mine permitting lags - Jael Holzman, Hannah Northey, E&E News | The U.S. could hold enormous potential to produce these EV metals. Nevada is chock-full of lithium potential and experiencing a jolt in exploration for the metal. One company in Idaho is trying to mine the state’s “cobalt belt.” Others in Alaska want to develop a coastal graphite deposit that could be one of the world’s largest — a hypothetical boon for U.S. battery makers. But mining these materials can often require a lengthy environmental review at the federal level. That could be because the deposits are found on federal lands, are located near an endangered species or pose a risk to protected natural spaces like wetlands — creating a tension between the need to get metals as fast as possible for climate action and rigorous U.S. environmental protection laws.

▶ The nuclear policy America needs - Matthew Yglesias, Slow Boring | I think the real problem here is both proponents and critics treating “pro-nuclear” as an identity rather than a policy agenda. It’s more useful to think in terms of concrete policy ideas. For example, if a state is considering a regulatory mandate about what kinds of electricity its utilities buy, that could be a renewables mandate (which wouldn’t include nuclear) or it could be a zero-carbon mandate (which would). On this, I am strongly pro-nuclear — don’t turn down carbon-free electricity. If the nuclear hype guys are wrong, nothing will come of it. If they’re right, we’ll be glad the regulations accommodated that. Similarly, it’s just insanity to prematurely retire existing nuclear power plants. The problem with these light water reactors is they are insanely expensive to build. Having built them, we should use them.

▶ SpaceX breathes fire in South Texas for the first time in 2022 - Eric Berger, Ars Technica | SpaceX ignited engines on both the first and second stages of its Starship launch system on Wednesday, signaling that it is getting closer to a test flight of the massive rocket later this year. … These two static firings, which are intended to test the plumbing of the rocket's liquid oxygen and methane propellant systems, are significant. They are the first static fire tests of 2022 at the South Texas launch site. Moreover, these vehicles—dubbed Booster 7 and Ship 24 to reflect their prototype numbers—could be the ones that SpaceX uses for an orbital launch attempt. Finally, this is the first time SpaceX has test-fired its new version of the Raptor engine, Raptor 2, on a rocket. …These tests follow a year-long period of development work by SpaceX to mature the design of the Starship vehicle from a prototype used for short, 10 km hops into a vehicle that can climb above Earth's atmosphere and then survive the fiery return back to the planet's surface.