🔥 The prospects for geothermal energy are heating up

A recent Wall Street presentation by key startups has boosted my optimism about this emerging sector

Drill, baby, drill — but not for oil and natural gas. It’s easy to get excited by the potential of geothermal energy. For starters, that potential is pretty massive. Advocates call geothermal the “sun beneath our feet,” so much so that it’s a cliché. Yet that description is no exaggeration. The Earth’s molten core is roughly as hot as the surface of the sun — due in part to the continual decay of naturally occurring radioactive elements — and will generate heat for about as long as our local yellow star does.

And that’s just the core. There’s some 40 times as much crustal thermal energy than the energy of the planet’s combined reserves of uranium, seawater uranium, lithium, thorium, and fossil fuels. Extracting “just 0.1 percent of the heat content of Earth could supply humanity’s total energy needs for 2 million years,” according to the US government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy.

Since you’re already probably thinking about supervolcanoes, let’s go there. Yes, it’s theoretically possible to tap the caldera system under Yellowstone National Park. Doing so has been off limits to developers since the 1970 Geothermal Steam Act in order to preserve the park’s pristine environment — not due to fears of accidentally causing a supereruption. Indeed, a 2017 study from the Jet Propulsion Lab suggests that one possible solution to preventing a future eruption — we’re actually due for one — is to siphon off excess energy by drilling holes around the perimeter of the caldera. That heat could then be used to generate electric power for 20 million homes for centuries. From the report “Defending Human Civilization from Supervolanic Eruptions”:

Thus we can anticipate that an Enhanced Geothermal System extracting 20GW (thermal) from the perimeter of a supervolcano could generate 3.46 GW of electrical power for a cost of $3.46 billion, delivering power at under (perhaps well under) $0.10/kWh, even if the entire length of the holes must be drilled through rock as hard as granite. This is a competitive price for electric power — an unexpected bonus since our main purpose is to prevent a supervolcano catastrophe. However, this bonus may be the critical factor in getting decision maker approval for such an approach.

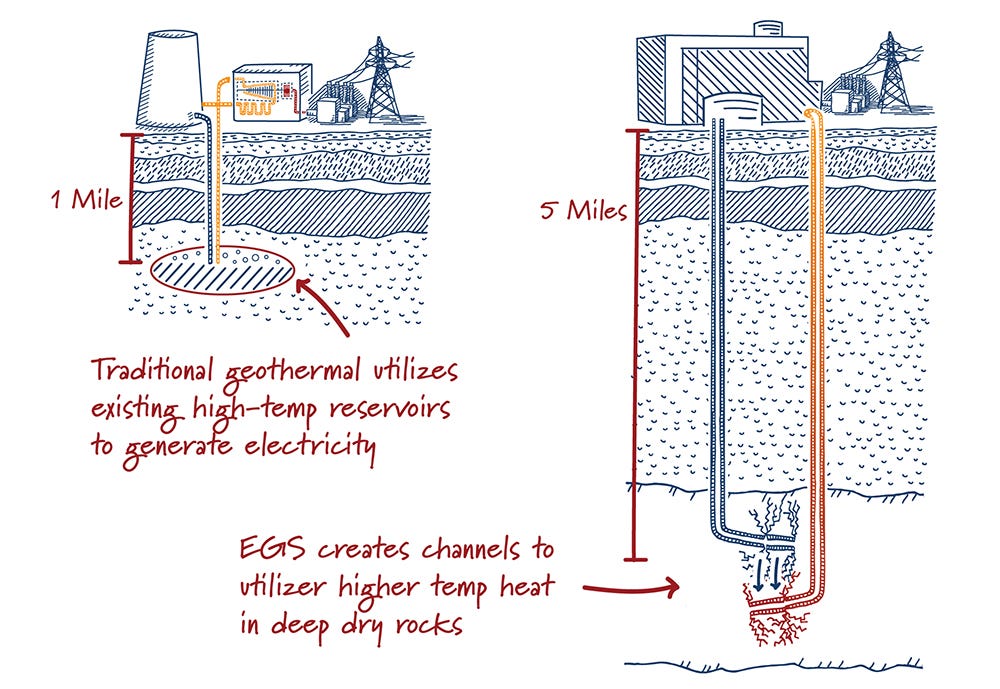

That said, none of the three geothermal startups that recently addressed a Goldman Sachs energy services symposium pitched the promising prospects of drilling into the Yellowstone supervolcano. Now keep in mind that nearly all of the world’s installed geothermal capacity depends on naturally occurring geothermal reservoirs. In the US, most of that capacity is in California and Nevada. But these companies all do something a bit different. They want to engineer such reservoirs or go superdeep:

The companies:

Fervo Energy, which specializes in using a modified form of hydraulic fracturing to extract heat energy from hot rocks by injecting water through them.

Sage Geosystems, which employs a closed-loop system where cooled fluid is pumped down from the surface in the outer ring of a double-walled tube, returning via the inner tube.

Quaise Energy, which plans to combine conventional rotary drilling with

millimeter-wave beam technology — first developed for nuclear fusion research — to drill down more than 12 miles where temperatures approach 1000 degrees.

Setting aside for a moment what the CEOs of these firms had to say, it’s good news that they were presenting to a Wall Street conference attended by exactly the sorts of companies that they might want to eventually partner with. Indeed, the existence of a massive oil and gas industry is another key reason to be excited about geothermal. Jamie Beard, founder and executive director of the Geothermal Entrepreneurship Organization at the University of Texas at Austin, spoke persuasively to me about this late last year. And it’s not just potential investment dollars that the sector can provide. Beard:

We have an existing, globally present industry with millions of highly trained individuals in the workforce that are perfectly suited to take geothermal to scale really fast. … In leveraging that workforce to do this, we actually avoid a lot of the job losses and disruption that’s forecasted for the industry. We don’t have to retrain geophysicists to install solar panels. We can let geophysicists do what geophysicists do best, but for geothermal instead of hydrocarbons. That’s what gets me really excited about geothermal: We have such assets on the table here. There’s a Ferrari in the driveway. It’s just a matter of hopping in and pressing the gas. … I’ve listened to enough people, particularly in oil and gas, to say that if we did do geothermal at oil and gas scale, it would solve energy and meet world energy demand by 2050.

Back to the conference. I certainly loved this answer from Fervo CEO Tim Latimer when a Goldman Sachs analyst asked him some of the challenges the company faces:

When we founded the company in 2017, no one in the investment community, no one in the services community, no one in the customer community wanted to talk about geothermal. And you can tell it’s a night-and-day difference now, spurred in large part by some of these grid reliability events, spurred by more aggressive climate policies, spurred by ESG pressure. So it’s different challenges now than we had before. … If you had asked … me two years ago, I would have said “I sure hope we can find somebody to buy our product.” And now it’s almost the reverse. … Because of the California Public Utility Commission ruling, because of Google’s 24/7 carbon-free energy commitment and the many corporates following in their footsteps, we’ve now gone from a power sector and policy environment that wasn’t all that interested in geothermal to … “Why can’t you all have a bunch of this on the grid tomorrow?”

Even better than Latimer’s optimistic take on geothermal demand — driven by both the private and public sector — is that he didn’t immediately mention regulatory issues as a key challenge. While I doubt regulatory barriers are no longer an issue, it may be a good sign that they weren’t his go-to response. That said, such barriers are obviously still a problem, which is one reason Sage CEO Lev Ring said he liked doing business in Texas. But Washington is a problem, too, including a permitting process on federal lands that requires exploration or development to meet National Environmental Policy Act guidelines. As a Bloomberg editorial noted recently, “Geothermal projects routinely face permitting hassles for seven to 10 years.”

Perhaps most encouraging were comments from Quaise CEO Carlos Araque who, like Latimer, noted that it wasn’t so long ago that geothermal was a “hard sell.” But no longer. Araque: “I think the world has started to realize that to succeed in the energy transition we’re going to need much more than wind, solar, and batteries. ... [Geothermal] can eventually scale to the terawatt scale we’re going to need to decarbonize.” Araque has previously noted that global energy demand is predicted to grow by 50 percent by 2050. And that demand, along with the inadequacy of solar and wind, such as the intermittency of those renewable sources, will fuel further interest in geothermal.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning a new non-profit organization, Project Innerspace, dedicated to promoting geothermal energy. Specifically, it wants to “catalyze geothermal development into terawatts of output globally, at a cost competitive with solar and wind” by doing two things: first, producing high-resolution geothermal prospecting maps; second, funding teams to “drill and develop first-of-their-kind power or heat producing geothermal projects in strategic locations globally.” More here:

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples of those interviews:

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

AI expert Avi Goldfarb on machine learning as a general purpose technology

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy