⚛ Don't take the emerging Nuclear Renaissance for granted

Opponents are using Russia's invasion of Ukraine as evidence the world is too unstable for such a supposedly dangerous energy source

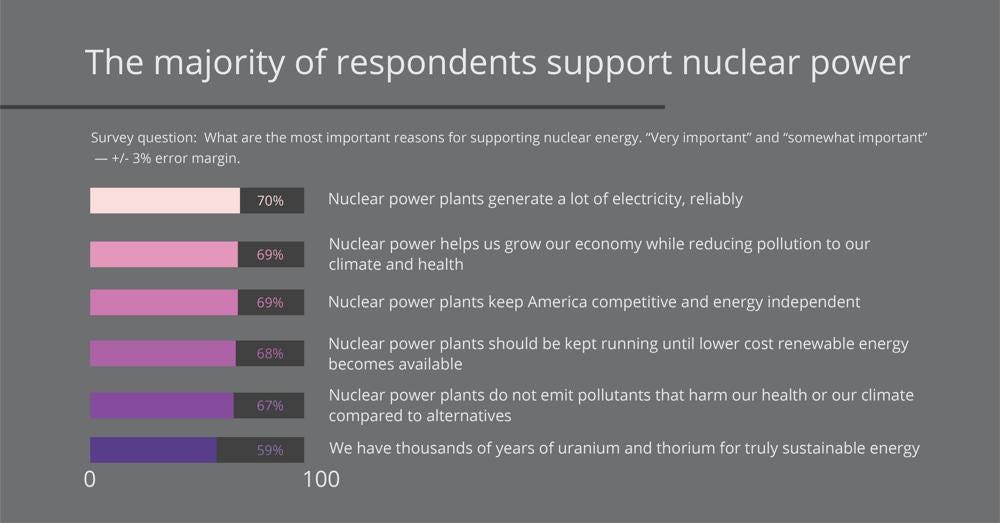

For all my optimistic Up Wing analysis and speculation about an emerging New Atomic Age (and I hope also a first Geothermal Age), nothing is assured. Technology must continue to advance both scientifically and economically. And it must successfully fight its way through an overgrown, and prickly regulatory thicket. Then there’s public opinion. True, we’ve seen a resurgence in public support for nuclear energy thanks to rising energy prices, concerns about how geopolitical instability affects fossil fuel supplies, and climate change. Check out the encouraging results of the annual ecoAmerica American Climate Perspectives Survey, released earlier this week:

Maybe these strong numbers aren’t so surprising given that public support for nuclear does tend to track energy prices. But I also like that 69 percent number for the statement “Nuclear power helps us grow our economy while reducing pollution to our climate and health.” Climate change is a long-term concern, one that is likely to grow in importance to the public, thus providing a higher floor for support of “elemental” energy.

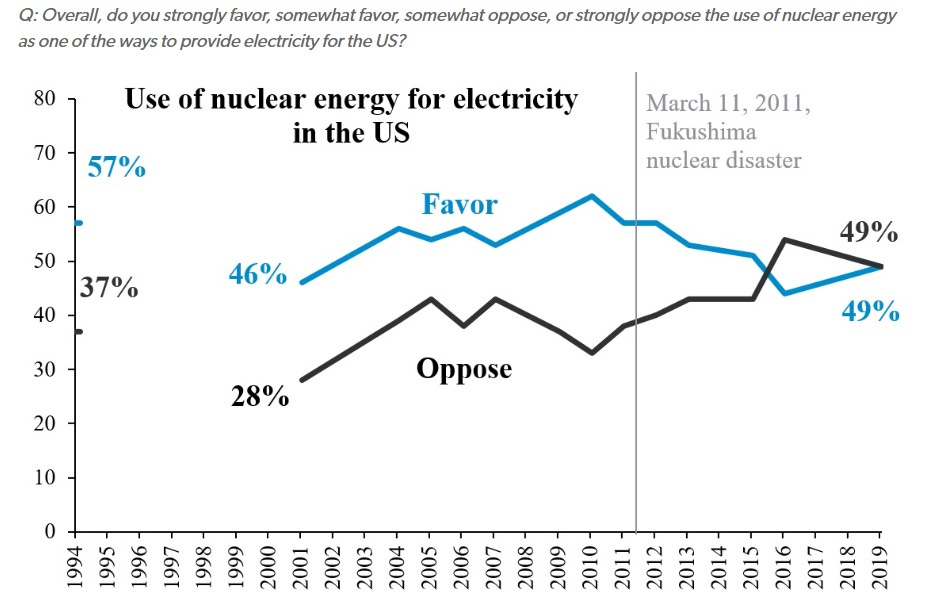

But what if something goes wrong? What if there’s another Fukushima-level event that seizes public attention in the worst possible way? The below poll suggests that the 2011 meltdown was hardly a plus for nuclear in the United States:

Nuclear power plants as weapons of war

What’s more, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raises a new concern: the weaponization of nuclear power plants. This from the Associated Press the other day: “Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, built during the Soviet era and one of the 10 biggest in the world, has been engulfed by fighting between Russian and Ukrainian troops in recent weeks, fueling concerns of a nuclear catastrophe.” And from Bloomberg today:

The UN’s nuclear agency ramped up its warning about Ukraine’s Zaporizhizhia nuclear power plant, saying the facility may soon lose power and shut down its last remaining operating reactor after sustained shelling in the area. “This is an unsustainable situation and is becoming increasingly precarious,” the agency’s chief said.

No, reactors can’t explode like a bomb. And Zaporizhzhia is built with reinforced concrete, making it tough to damage through accidental artillery shelling. Nor is it likely that either side would intentionally shell the plant. As one expert told Vox, “The likelihood of an intentional attack on the [plant] that leads to a major nuclear disaster is low. Moscow would have a lot to lose and nothing to gain from such an outcome, given the reactor’s proximity to Russian forces and population.” The most realistic concern is if the fighting leads to a loss of electricity, and the plant is unable to cool the reactor core, eventually leading to a meltdown. This is what happened to three reactors at Fukushima.

To die-hard nuclear opponents, such a risk at one reactor anywhere makes the case against nuclear energy everywhere. But consider Fukushima. It is one of only two nuclear accidents, along with Chornobyl, to merit the most severe rating on the International Nuclear Event Scale. Yet no fatalities have been found directly attributable to radiation exposure (with some 1200 attributed to the mass evacuation.) Within 14 months of the accident, Japan halted all of its nuclear power production. Germany did much the same, immediately shutting down almost half of its nuclear power plants and promising to mothball all the remaining ones by 2022. Neither nation was willing to risk future nuclear accidents and deaths. Well, at the time, at least.

Just how risky are nuclear accidents?

Then came the unintended consequences. Researchers estimate that reduced power use in Japan led to an additional 1,280 winter deaths from 2011 through 2014. (And because the data only cover the 21 largest cities in Japan, 28 percent of the total population, the total effects for all of Japan are almost assuredly even larger.) Likewise, researchers looking at the German nuclear phase-out estimate nearly 500 additional deaths a year due to increased pollution from replacing nuclear power with coal-fired production in that country.

It’s hard to square these numbers against the “existential” risk that environmentalists attribute to climate change. Of course, the anti-nuclear media and entertainment industry will no doubt play up any accident, whether technical or war-related, to again turn the public against nuclear.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.