Is a new Atomic Age finally here?

Also: The left continues to confront its ‘big economic mistake’ — yay!

“Infinite ignorance is a necessary condition for there to be infinite potential for knowledge. Rejecting the idea that we are ‘nearly there’ is a necessary condition for the avoidance of dogmatism, stagnation and tyranny.” - David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity

In This Issue

The Micro Reads: automation, nanotechnology, nuclear fusion, and more …

The Short Read: The left continues to confront its ‘big economic mistake’ — yay!

The Long Read: Is a new Atomic Age finally here?

The Micro Reads

🤖 Simulating the future of global automation, its consequences, and evaluating policy options - Seth G. Benzell, Victor Yifan Ye | So many analysts and journalists focus on the downside of automation, it’s always helpful to remind ourselves of the other side of the trade. From the analysis: “If automation continues at its historical pace, it will increase US GDP by about 5% in 2050 (versus a scenario with no new factor-share-shifting automation technologies). Western Europe and Japan, which have high wages, high capital use intensity, and aging populations, also benefit disproportionately.” The analysis also sketches out how a universal basic income can make automation a “win-win for all ages and skill groups.”

🌐 The world economy’s shortage problem - The Economist | An ominous kicker to this piece: “Disruptions often lead people to question economic orthodoxies. The trauma of the 1970s led to a welcome rejection of big government and crude Keynesianism. The risk now is that strains in the economy lead to a repudiation of decarbonisation and globalisation, with devastating long-term consequences. That is the real threat posed by the shortage economy.”

🔬 A Big Bet on Nanotechnology Has Paid Off - Chad Mirkin, Scientific American | The Northwestern University professor of materials science and engineering outlines the successes of the National Nanotechnology Initiative, created at the end of the Bill Clinton administration. The medical, chemical, optical and clean energy industries are among those sectors benefiting. All great stuff. But I stumbled over this line: “We’ve come a long way from tiny robots.” I immediately thought of the tiny machines, or “molecular assemblers,” envisioned by K. Eric Drexler in his 1986 book Engines of Creation. Imagine a real-life version of Star Trek’s replicators. It was that sort of nanotech that Congress likely imagined when first funding the NNI, not a branch of materials science. But as science journalist Adam Keiper noted in a 2010 Wall Street Journal commentary:

So far, none of that federal R&D funding has gone toward the kind of nanotechnology that Drexler proposed, not even toward the basic exploratory experiments that the National Research Council called for in 2006. If Drexler's revolutionary vision of nanotechnology is feasible, we should pursue it for its potential for good, while mindful of the dangers it may pose to human nature and society. And if Drexler's ideas are fundamentally flawed, we should find out—and establish just how much room there is at the bottom after all.

Seems that Mirkin, at least, is happy to keep the focus where it’s at.

💥 Disruptive Innovations VIII - Citi | The Wall Street bank publishes its eighth report looking at “some of the leading-edge concepts across sectors and identify new products which could ultimately disrupt their marketplace.” Among them: psychedelic drugs for treatment-resistant depression and anxiety; plant-based alternative proteins; ammonia as fuel in jet engines; de-polymerization to avoid plastic waste filling landfills; 3D architecture in semiconductors; more mRNA vaccines; and removing carbon from the atmosphere.

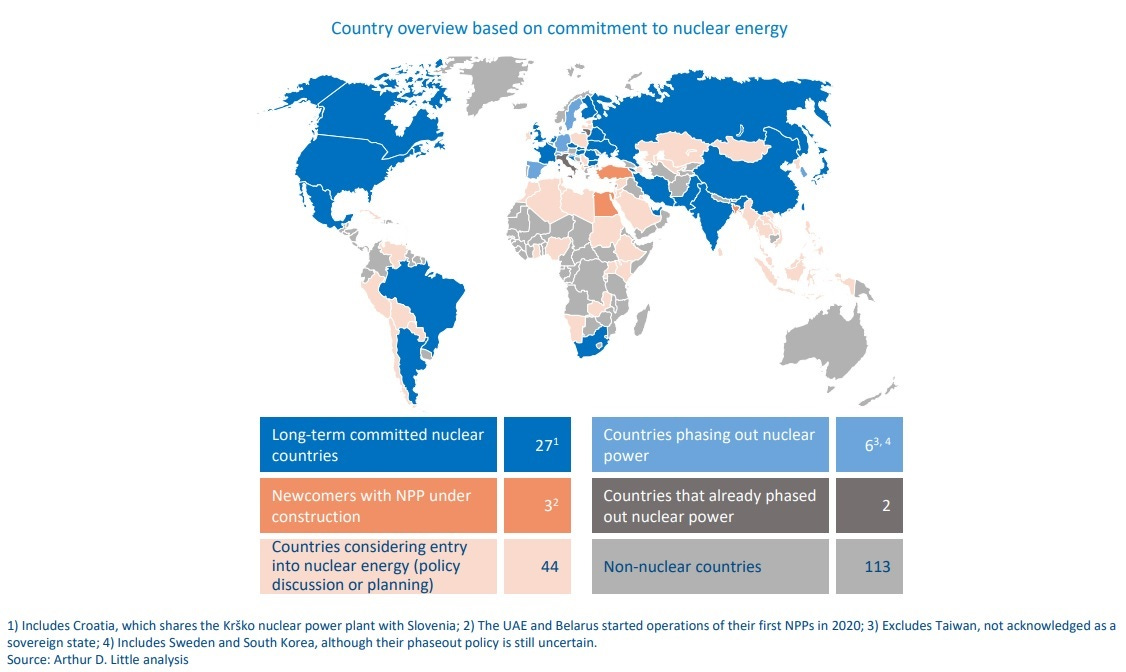

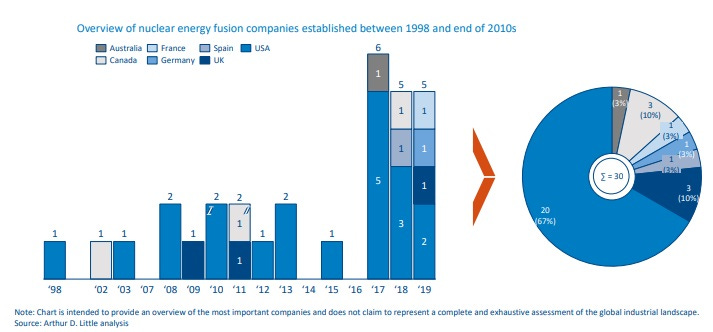

⚡ The next big bang in emissions-free energy - Arthur D. Little | The management consultancy is out with a big report on nuclear fusion (which provided a couple of nuclear-themed charts below). From the conclusion: “Overall, nuclear fusion does represent a significant opportunity for the energy industry and the race to decarbonize the world, and investors are aware of it. From an investment perspective, one could think of it as a lottery ticket: as the opportunity is uncertain, it is not reasonable to bet only on nuclear fusion as the solution to today’s energy problems.”

The Short Read

🔎 The left continues to confront its ‘big economic mistake’ — yay!

According to the “middle-out” theory of economics (a term I first heard used by Senator Elizabeth Warren), the key driver of growth is consumer spending. And since rich people save “too much,” their income and wealth must be redistributed to the higher-spending middle class in various forms such as universal healthcare, free tuition, and maybe even a universal basic income. “Purchasing power” is what really matters. Oh and tax corporations more, too, of course.

But middle-outers tend to have much less to say about the supply side of the economy and boosting American productivity. Indeed, they often dismiss pro-productivity policies as off-topic since everyone knows higher worker productivity hasn’t translated into higher worker pay for decades. (This isn’t true by the way.)

But now we are seeing what happens when spending power outpaces an economy’s productive capacity. The result: shortages, inflation, and slowing in overall economic activity. So it’s good news that center-left economic writers and pundits seem to be creating a permission structure for Democrats to think a lot more about the supply side of the economy. I wrote recently of New York Times columnist Ezra Klein and his piece “The Economic Mistake the Left Is Finally Confronting.”

Now we have “America is Running Out of Everything” by Derek Thompson in The Atlantic. Thompson highlights the many shortages — semiconductors, shipping containers, workers — affecting the recovering global economy, including here in the United States. The following insight, in particular, seems to be a real eye-opener: “The one lesson of the Everything Shortage is: You cannot redistribute what isn’t created in the first place. The best equality agenda begins with an abundance agenda.”

Still, it’s strange that it took a pandemic to teach the lesson of the Everything Shortage. No less a left-wing economic authority than Paul Krugman has famously said: “Productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” Raising the productivity of workers and thus the productive capacity of the US economy must be at the heart of any “abundance agenda.”

So what might such an agenda look like? Klein and Thompson suggest the sorts of things most economists would probably agree with: housing and labor market deregulation, more immigration, more science research (including new ways to spend that money, such as a greater emphasis on innovation prizes). I like those ideas, too.

But “supply-side” progressives must go further, such as looking at environmental policies that stymie the development of new nuclear and geothermal energy sources. Supply-side progressives also need to think more seriously about how taxes affect innovation and the high-impact entrepreneurship that gives us the mega-companies of the future (as well uberbillionaires). In the new working paper “The Effects of Taxes on Innovation: Theory and Empirical Evidence,” Harvard University economist Stefanie Stantcheva writes that “the efficiency costs from reduced innovation may need be taken into account when setting taxes and to pinpoint the factors on which the magnitudes of these costs depend.”

I’m skeptical that many of the recent tax proposals coming from progressives are thinking seriously about the “efficiency costs from reduced innovation.” And if you’re looking for more of my “abundance agenda” ideas, keep reading Faster, Please!

The Long Read

⚛ Is a new Atomic Age finally here?

Japan is the only nation to have ever been attacked with nuclear weapons. And the 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was one of only two nuclear accidents, Chernobyl being the other, to merit the most severe rating on the International Nuclear Event Scale. So if you’re looking for a sign that we may be entering a New Atomic Age, Japan’s re-embrace of nuclear energy is probably a momentous one. The nation’s new prime minister, Fumio Kishida, says it’s “crucial” the nation re-start the nuclear plants that were shut down after the Fukushima disaster.

Pro-nuclear politicians like Kishida simply see no other way to both reduce carbon emissions and supply a reliable source of power to the nation. Last February, the nation’s energy minister told the Financial Times that heavy snowfalls almost led to power cuts the previous month: “Solar wasn’t generating. Wind wasn’t generating. I’m trying to persuade everybody that in the end we need nuclear power.”

It’s a message that seems likely to have appeal globally right now as the entire world seems to be experiencing an energy crunch. From The Washington Post:

Energy is so hard to come by right now that some provinces in China are rationing electricity, Europeans are paying sky-high prices for liquefied natural gas, power plants in India are on the verge of running out of coal, and the average price of a gallon of regular gasoline in the United States stood at $3.25 on Friday — up from $1.72 in April.

As the global economy recovers and global leaders prepare to gather for a landmark conference on climate change, the sudden energy crunch hitting the world is threatening already stressed supply chains, stirring geopolitical tensions and raising questions about whether the world is ready for the green energy revolution when it’s having trouble powering itself right now.

And it’s not just Japan turning to nuclear. In France, President Emmanuel Macron says his “number one objective is to have innovative small-scale nuclear reactors in France by 2030 along with better waste management.” Britain, meanwhile, is in talks with US nuclear reactor company Westinghouse on building a new atomic power plant. And there are more. “National leaders around the world are announcing big plans to return to nuclear energy now that the cost of natural gas, coal, and petroleum are spiking, and weather-dependent renewables are failing to deliver,” tweets nuclear energy advocate Michael Shellenberger. (Along the same lines, I highly recommend the new Foreign Policy essay “In Global Energy Crisis, Anti-Nuclear Chickens Come Home to Roost” by Ted Nordhaus.)

And what about solar and wind? What role do they have to play going forward? This is the question I asked in recent podcast with Arthur Turrell, deputy director at the Data Science Campus of the Office for National Statistics in the UK and the author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet. His answer:

Renewables are already the cheapest form of power — except keeping existing nuclear fission plants open. But I think in almost anything that you do in life, it's useful to have a portfolio of things with different strengths and weaknesses that you can draw upon. . . . [Renewables] work right now and they're very cheap, but on the disadvantages side, the energy that they tap into is very diffuse. It's spread out over large areas, and that means that they need vast areas to work. So for example, to power the UK solely using onshore wind turbines would mean covering 17 percent of the country with turbines, which is a huge amount. It's absolutely enormous, and as we've found this summer in the UK, the energy from renewables is not always reliable. So we've had a very un-windy summer in the UK here. Sadly, it hasn't been that sunny either, but sometimes you want types of power that aren't so reliant on the weather to provide that baseload energy. . . .

So that's one reason. Another reason in the long run why we might want fusion energy — and excuse me if this sounds rather futuristic — is that we are not going to explore the solar system as a species using a coal-fired spaceship. And in fact, if you look at what realistic trips outside of our kind of solar system's backyard would have to be powered by — or even the Earth's backyard, I should say — fusion is one of the best candidates for that because it packs a lot of energy into a very small amount of space. In fact, it's 10 million times higher in energy density than coal.

I don’t pretend to know the exact future composition of the energy portfolios of America and other nations. But I think the odds that nuclear fission/fusion and geothermal will play major roles have increased significantly of late. And that’s good news because a prosperous, healthy world (or worlds) is going to need lots of clean energy.