🔁 America: Everything, everywhere, all at once

US economic decline is neither inevitable nor likely in the 21st century

Quote of the Issue

“The whole machine learning as applied to deepfake technology, that's an extraordinary step forward in visual effects and in what you could do with audio. There will be wonderful things that will come out, longer term, in terms of environments, in terms of building a doorway or a window, in terms of pooling the massive data of what things look like, and how light reacts to materials. Those things are going to be enormously powerful tools.” - Christopher Nolan

The Essay

🔁 America: Everything, everywhere, all at once

Ask a well-read person to name a late 20th-century, big-think book about geopolitics and world history, and they might well name The End of History and the Last Man by political scientist Francis Fukuyama. Published in 1992, The End of History explains the historical triumph of (and the lack of viable alternatives to) liberal democratic market capitalism. Although conceding that “some present-day countries might fail to achieve stable liberal democracy, and others might lapse back into other, more primitive forms of rule like theocracy or military dictatorship,” Fukuyama concluded that “the ideal of liberal democracy could not be improved on.”

The subsequent global economic acceleration, especially in the United States, and pro-market shift across Asia made Fukuyama look prescient. But just five years earlier, there was another book that seemed a strong candidate to be the one people would still talk about in the 2020s. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 by historian Paul Kennedy was much discussed in the late 1980s. Critics of the Reagan and Bush administrations were especially taken by Kennedy’s diagnosis that the United States, like other hegemons of the past, had become afflicted by “imperial overstretch.” Too much deficit spending on the military, too little investment in the economy’s productive capacity. As with Fukuyama, events initially bolstered Kennedy, particularly the “Black Monday” stock market crash on October 19, 1987, and the nasty 1990-91 recession. Kennedy’s advice for Washington:

The task facing American statesmen over the next decades, therefore, is to recognize that broad trends are under way, and that there is a need to "manage" affairs so that the relative erosion of the United States' position takes place slowly and smoothly, and is not accelerated by policies which bring merely short-term advantage but longer-term disadvantage.

Yet just as the last decade of the 20th century seemed to support Fukuyama’s thesis, it seemed to undercut Kennedy’s. Although China was clearly rising, America looked to be rising as well, with its economic acceleration making Kennedy’s fiscal concerns far less relevant.

But as America moved past the boomy 1990s and the turn of the century, Kennedy’s diagnosis gained salience even if the book faded from the punditocracy conversation. The 9-11 terror attacks and Iraq War, the Great Recession, and the Not-So-Great Recovery created an enormous sense of pessimism about America’s future.

Then there’s the Kennedyesque thesis of Donald Trump’s 2016 “Make America Great Again” presidential campaign was that America is a country in decline — especially relative to China — because of, in part, too many foreign wars and too little nation-building at home. (Of course, Trump didn’t much care about debt and deficits, other than the trade deficit.)

His victory was interpreted by many as a repudiation of Fukuyama’s triumphant liberalism. And many US policymakers started looking for lessons from China’s success. Time for another of the periodic political infatuations with the notion of government supporting “strategic sectors” with subsidies and trade preferences. Chinese state capitalism with American characteristics. Even more so than Trumponomics, Bidenomics is a clear embrace of industrial policy.

American greatness, by the numbers

But let's step back and briefly examine the decline thesis. Is America in decline? Start with a comparison to other advanced economies, namely those in Europe. A few fun facts from the recent Financial Times column “Europe has fallen behind America and the gap is growing” by Gideon Rachman:

In 2008 the EU’s $16.2 trillion economy was 10 percent bigger than America’s $14.7 trillion economy. By 2022, the $25 trillion U.S economy was a third bigger than the combined EU-UK economy.

The seven largest tech firms in the world, by market capitalisation, are all American with only two European companies in the top 20, ASML and SAP. Rachman: “The development of AI is also likely to be dominated by American and Chinese firms.” (Europe will apparently settle for being a leader in AI regulation.)

Although Britain has a few top universities, such as Cambridge and Oxford, “the leading universities that feed the pipeline of tech start-ups in the US are lacking in the EU.”

What’s more, the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency gives the US easy credit access, deep domestic capital markets offer the same for US companies, and the US economy is powered by cheap and plentiful domestic energy supplies. So many pluses. Rachman concludes: “The aggregate figures are shocking. Underpinning them is a picture of a Europe that has fallen behind — sector by sector.”

The China (slowdown) syndrome

Now, China. The days of anything even close to double-digit growth are over. And even low single digit growth isn’t going to be easy given its demographic problems and inability to push forward the technological frontier as America does.

These challenges are outlined in the new paper, “The Neoclassical Growth of China” by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, (University of Pennsylvania, NBER, and CEPR), Lee Ohanian (UCLA), and Wen Yao (Tsinghua University). The paper’s mention of “total factor productivity, or TFP, refers to the efficiency with which inputs of capital labor are used in an economy, and if typically used as a way of measuring an economy’s technological progress or innovativeness. From the paper:

Since becoming a middle-income country in 1995, China’s growth performance has been remarkably similar to that of other East Asian growth miracles at the same stage of development. … China has been growing because it is accumulating capital and is catching up with the world’s technological frontier. But China’s technology catch-up is slowing considerably. This fact, combined with the likelihood of additional slowing and a declining population, means that China’s growth can only slow down, perhaps significantly. Our future forecast for China’s economy, which assumes a continued comparatively high savings rate and employment-to-population ratio, may be too optimistic should either of these factors decline. … With a population growth rate in the long run of −1.19% projected by the UN (which assumes a recovery in fertility from the current 1.08 children per woman to 1.48), TFP needs to grow 1.19% a year just to keep total income constant (given constant employment-to-population and capital-worker ratios). Delivering a growth rate of 3% would require a TFP growth rate of 4.19% in an economy with a middle-high income already. While not out of the realm of possibility, given the upside potential of AI and automation, the historical record is not sanguine about the likelihood of a long-run TFP growth rate of 4.19%. A shrinking population and slowing TFP catch-up are substantial headwinds facing China.

A couple of additional points. Fernández-Villaverde thinks the UN is too optimistic about Chinese population growth, or, rather, the lack of it. As he told me in a recent podcast chat, “China is looking at a demographic abyss, and unless the Communist Party is able to change that, China is going to be a way less important economy in the middle run.”

Second, policy matters when it comes to productivity growth. Although China has been moving in the wrong policy direction recently — too much state capitalism, not enough market capitalism — maybe that changes at some point. As the economists observe, “On the other hand, our forecast may be too pessimistic if China implements new institutional reforms that improve economic efficiency to reverse its declining TFP catch-up rate.”

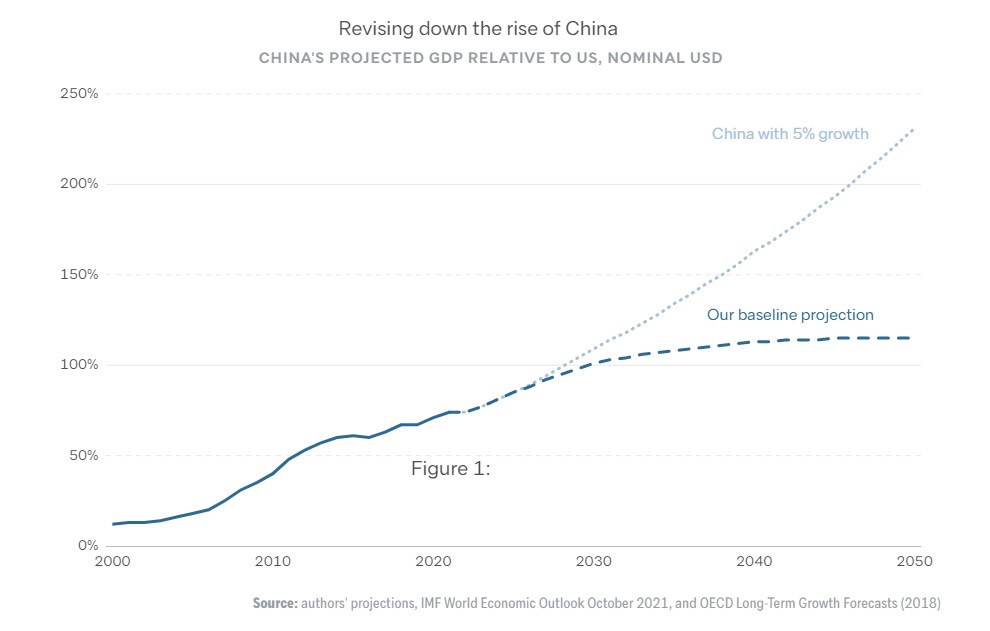

But even if China can manage to grow at 3 percent, that’s short of the 5 percent or 6 percent rate implied in forecasts of a “Chinese Century.” At a 3 percent pace, “China would still likely become the world’s largest economy,” concludes a recent report from Australia’s Lowy Institute. “But it would never establish a meaningful lead over the United States and would remain far less prosperous and productive per person than America, even by mid-century.”

Also keep in mind that if AI-machine learning-GenAI helps China grow faster, it’ll likely do the same for the US, if not more so. The lack of diversity and quality in Chinese data sources, dependence on foreign chips and software for its AI infrastructure, and the difficulty of fostering innovation and collaboration in a closed and controlled environment all bode poorly for Chinese productivity growth, concludes a recent analysis of the Sino-American tech race in The Economist.

That said, I think America can outgrow China over the long-run, thanks to its innovative and entrepreneurial free enterprise system and its ability to attract global talent. On that latter point, I highly recommend the new report “Immigration Policy Is Innovation Policy” from the Economic Innovation Group.

There’s nothing wrong with America that can’t be fixed by doubling-down on what’s right about America: openness and freedom. Drawbridge down, not up. The end of history in the Fukuyama sense? Yes. But not the end of American superpower dominance if the US remembers the secrets of its success.

Micro Reads

▶ Chuck Schumer Joins Crowd Clamoring for AI Regulations - John D. McKinnon, NYT | But imposing new regulations on a set of technologies that are still under development will be difficult for Congress, which often waits years or even decades before establishing guardrails for new industries. In addition, lawmakers will be trying to impose new rules in a number of areas—such as copyright and liability—where tech companies have battled with other industries and consumers for years.

▶ Flying taxis: lack of landing spots will delay sector take-off - Lex, FT Opinion | Yet even if vehicles receive regulatory approval, infrastructure remains a problem. Air taxis, or eVTOLs (electric vertical take-off and landing), need large, flat, obstacle-free surfaces to land safely. If they are too noisy, city dwellers will complain. … Companies plan to use existing heliports. Archer, for example, hopes to fly between Downtown Manhattan’s heliport and Newark airport. But to create useful services they need multiple, convenient, city-centre spots. Without a network of landing and take-off points, flying taxi services will be grounded.

▶ How Christopher Nolan Learned to Stop Worrying and Love AI - Maria Streshinsky |

▶ Purely AI-generated songs declared ineligible for Grammy Awards - Benj Edwards, Ars Technica |

▶ Ultra-fast boxing robots could be used for real-life fighting game - David Hambling, New Scientist |

▶ Waymo, Cruise Driverless Cars Are Suddenly All Over San Francisco - Edward Ludlow, Bloomberg | Waymo’s current fleet consists of about 200 cars in San Francisco. The company is doing about 10,000 trips a week across the city and the Phoenix area, and its goal is to do 10 times that volume of trips by next summer. Thousands of public users — not including Waymo employees — are riding in a limited patch of San Francisco, and the waitlist is at more than 80,000. A smaller roster of 1,000 “trusted testers” have access to cars that can travel through the entire city. Cruise, meanwhile, is averaging 1,000 trips a day in San Francisco, and on busy days has hit 2,000 trips. The company has 300 customized Chevy Bolt electric vehicles across San Francisco, Austin and Phoenix. Tens of thousands of people are signed up to ride Cruise here, a spokesperson told me, and tens of thousands more are on the waitlist. The company’s goal is to hit $1 billion in robotaxi revenue by 2025.

▶ The impact of artificial intelligence on growth and employment - Ethan Ilzetzki and Suryaansh Jain, VoxEU |

No matter how hard it tries, the US government can not slow the forces of Creative Destruction. Other governments do it well, but luckily the US government just can not marshal itself to gain enough power. American Entrepreneurs and our ecosystem run on Hayek's version of economic coordination. The "Use of Knowledge in Society"

On both the topic of AI regulation (and avoiding foolish, centralized and bureaucratic controls) and on maintaining the ability to innovate, I wrote a piece on an alternative perspective that coheres with the one you present on your blog.

https://maxmore.substack.com/p/existential-risk-vs-existential-opportunity