👁 Can authoritarian China really out-tech America?

Also: The growthy immigration reform inside Build Back Better

“The Progress of human Knowledge will be rapid, and Discoveries made of which we have at present no Conception. I begin to be almost sorry I was born so soon, since I cannot have the Happiness of knowing what will be known 100 Years hence.”- Benjamin Franklin

In This Issue

Micro Reads: driverless trucks, nuclear fusion, tech clusters, and more …

Best of the Pod: My conversation with Azeem Azhar

Short Read: The growthy immigration reform inside Build Back Better

Long Read: Can authoritarian China really out-tech America?

Micro Reads

🚚 How autonomous trucks could fix our broken supply chains - Axios | Politician and thinkfluential Andrew Yang has warned that autonomous driving tech will lead to mass riots by truckers. But that’s not my concern right now. Early retirement and soaring demand for shipping have created a shortage of truck drivers, making supply-chain challenges worse. Highway-ready driverless trucks, ASAP

⚛ Record fundraising by a nuclear fusion start-up - Financial Times | I love new, revolutionary tech seems to be passing the market test, or at least the initial market test. Helion, a fusion energy company based in the US, has raised $500 million in venture capital — the largest amount of any private fusion company, signaling investor confidence in fusion technology. Helion hopes to build a successful demonstration plant by 2024, with the eventual vision of shipping container-sized power generators capable of powering 40,000 homes.

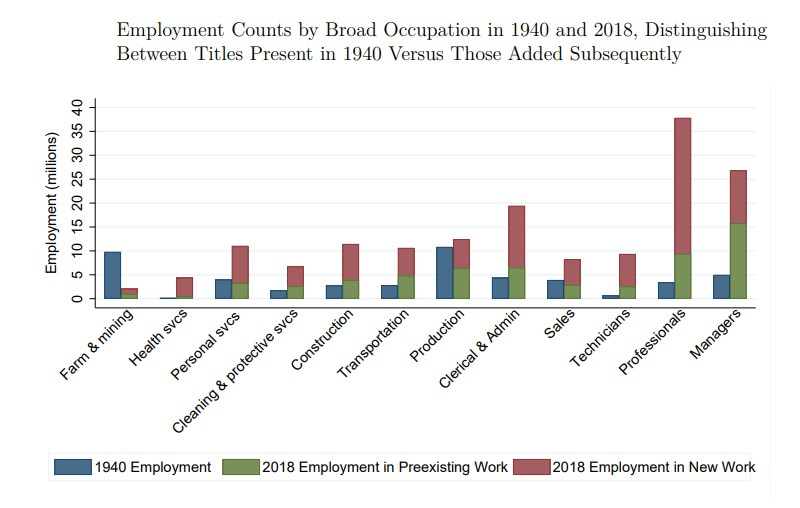

👨🏭 New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018 - David Autor, Anna Salomons, Bryan Seegmiller | Thanks to economist Carl Benedikt Frey for recently highlighting this 2018 paper: “The majority of jobs performed in 2018 did not exist in 1940. .. We document that, compared to preexisting (‘old’) work, new work arises disproportionately in middle-paid production and office work in the first four post-War decades. By contrast, new work creation since 1980 has increasingly concentrated in high-education specialties and, to a lesser extent, low-education personal services. “

🛢 Metals may become the new oil in net-zero emissions scenario - Lukas Boer, Andrea Pescatori, Martin Stuermer, Nico Valckx, VoxEU | In this new paper, researchers estimate that a global transition to clean energy will massively increase demand for key metals. The total value of production could rise more than four-fold for the period 2021-2040, rivaling the total value of crude oil production. To support investment that will expand the supply of these metals and ease the cost of transitioning to clean energy, the authors emphasize reducing policy uncertainty with a “globally coordinated climate policy; high environmental, social, labour, and governance standards; and reduced trade barriers.”

🥇 Winner Takes All? Tech Clusters, Population Centers, and the Spatial Transformation of U.S. Invention - Brad Chattergoon and William R. Kerr, NBER | This new working paper looks at US patents, identifying a reallocation of invention from major population centers to tech hub cities like San Francisco as software patents make up an increasing share of total patents. The authors conclude that, “Nonsoftware patenting is stable for most cities, with anchor tenants like universities playing important roles, suggesting the growing concentration of invention may be nearing its end.”

🧠 Dementia: A Public Policy Challenge - Timothy Taylor | The number of elderly Americans with dementia is growing as the population ages. Beyond the sharp decline in quality of life, caring for those with dementia is about four times as costly as caring for someone the same age without the disease. One stat quoted: “When aggregated to the U.S. population, the costs are estimated to have exceeded $500 billion in 2019 and are projected to increase to about $1.5 trillion by 2050.” While we should continue to look for ways to treat dementia with pharmaceuticals, reduce the costs of care, and prevent dementia in the first place with healthier lifestyles, the economist Taylor ends with a call for action: “It’s past time for an Operation Warp Speed aimed at dementia, which would guarantee that the government would purchase a certain quantity of the drug in exchange for meeting certain health and cost-per-patient targets.”

Best of the Pod

My conversation with Azeem Azhar

An insightful bit from my recent chat with the founder of Exponential View, where his podcast and newsletter deliver in-depth tech analysis, and author of the new book The Exponential Age: How Accelerating Technology is Transforming Business, Politics, and Society.

Pethokoukis: In the book, you quote a poll from last year: 60 percent said they felt the pace of change was too fast. And that was up considerably from five years ago. On the surface I think that would seem to support the idea that we’re in a period of rapid change. But I think of the book Future Shock from 1970 by Alvin Toffler. And the premise of that book was that we were in a period of rapid change. In fact it was so rapid, it was driving us all crazy. And that book came out just as a period of rapid growth and technological progress downshifted. We entered what some people call the “great stagnation.” Do you have any concern that people thinking life is going so fast might actually be some sort of contrarian indicator, and we’re not entering an Exponential Age?

Azhar: Oh, I love that question. I mean, people have certainly for the last 150 years felt that things are going too fast, and you can go back to the archives of the New York Times in the 1920s about elevators, and the turn of the 20th century about girls and boys reading books at night using electric light and parents being worried about that. I think what’s different this time, and what’s distinct to what happened after Toffler made his very impressive remarks 50 years ago, is that we can actually see and feel that shift in our real economies. In 2010, the world’s largest companies were companies of the 20th century. It was ExxonMobil and oil companies and General Motors and General Electric. These were technologies of the era, of Rockefeller and Ford and Edison. And by 2015, all of the world’s largest companies were essentially IT companies sitting on the top of semiconductor improvement rates. And so there is a distinct shift, and that’s been reflected by the market.

Short Read

🌐 The pro-growth immigration reform tucked inside the Biden Build Back Better plan

“Is that all there is?” That basically sums up my reaction — as expressed in the previous issue of Faster, Please! — to the potential growth impact of the Biden economic agenda.

I based that response on the modeling of economist Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics. According to Zandi’s calculations, if both the bipartisan infrastructure bill and the social welfare/climate bills become law (the former has already passed Congress and is merely awaiting President Biden’s expected signature), then real GDP growth would average 3.2 percent annually during Biden’s term and 2.2 percent over the next decade, compared with less than 2.8 percent annually and 2.1 percent over the next decade if the legislation fails to become law. So not a massive long-term difference. (And drilling down specifically on productivity growth, Zandi estimates that by 2031, the infrastructure law will have improved labor-productivity growth by 0.03 percentage points a year, notes the Wall Street Journal.) Of course, every little bit helps, and so does same-old, same-old growth off a higher base. But it doesn’t seem like much bang for the many trillion bucks.

But wait! Some readers think the above analysis misses something with a big potential impact. As described in the WSJ:

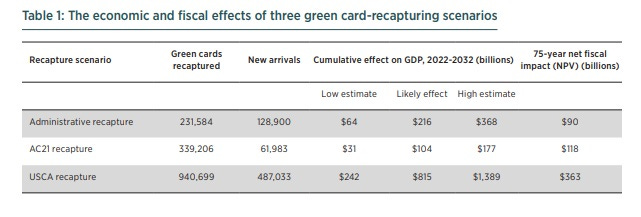

While Democrats haggle over the size and scope of legal protections for so-called Dreamers and other immigrants in the country illegally, they have also included a measure in the House bill that would recover hundreds of thousands of unused green cards over the last several decades and make them available to applicants waiting in line. Under the proposal, the unused green cards, which confer permanent U.S. residency, would be “recaptured” or put back in circulation and remain available until they are issued.

A report last summer by Jeremy Neufeld of the Niskanen Center, along with Lindsay Milliken and Doug Rand of Federation of American Scientists, looked at three proposals to recapture unused green cards, with the number ranging from a quarter million to nearly one million. Likewise, the benefit to economic growth ranges from around $100 billion over a decade to nearly $1 trillion over a decade. (A key difference between the two growth estimates is whether or not you think immigration boosts productivity growth. Spoiler . . . it does.)

Zandi doesn’t specifically mention immigration in the report I accessed. But he did have this to say in another recent one: “Immigration and working-age population growth should pick up given the Biden administration’s more relaxed immigration policies and a post-pandemic normalization of cross-border movement, but this won’t happen quickly.” That doesn’t sound like immigration was a big factor in the forecast, so maybe there’s room on the upside — at least if let more folks inside.

Long Read

👁 Can authoritarian China really out-tech America?

I always raise an eyebrow (at least mentally) when I watch science fiction where the bad guys have technology as advanced as the good guys. For example: In the classic Star Trek series, the oppressive Klingon and Romulans have spacedrives and weapons at least as good as those of the free and democratic Federation. Could such authoritarian regimes really occupy and push forward the tech frontier, especially across a range of superscience technologies?

Which brings us to China. There’s bipartisan concern in Washington about China’s increasing tech prowess, both for economic and military reasons. Also importantly, Beijing is presenting an alternate socioeconomic model to the democratic capitalism of America and the West, one which promises authoritarian governments both economic success and permanent political power.

Some American politicians are so concerned that they’ve been advocating the US copy, in its own way, China’s industrial planning efforts, such as the (now rebranded) Made in China 2025 initiative, a strategic plan to develop key technologies such as AI, robotics, electric vehicles, and aerospace. China’s recent successful test of a globe-circling, nuclear-capable hypersonic missile in August will surely exacerbate such fears, with some here calling it a “Sputnik moment.” This from the Financial Times really struck me: “One person said government scientists were struggling to understand the capability, which the US does not currently possess, adding that China’s achievement appeared ‘to defy the laws of physics.’” (The following image from the FT shows a “Long March” rocket — the same used for China’s new hypersonic glide vehicle— carrying China’s Chang’e-5 lunar probe.)

Yet the question remains: Can China’s more top-down, central planning approach match or even surpass the tech innovation and productivity of America’s more bottom-up, free enterprise system, one that generally eschews deeply interventionist industrial policy (at least for non-defense purposes)? Or to put it more simply: Can frontier innovation be sustained under autocracy?

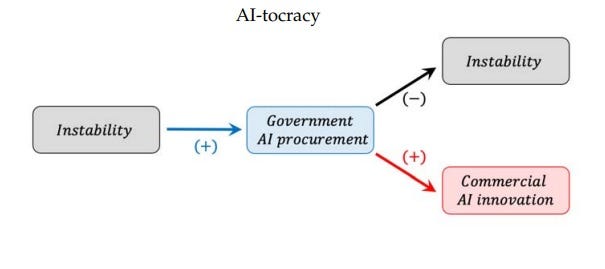

An affirmative answer to that question can be found in the new NBER working paper “AI-tocracy” by Martin Beraja (MIT), Andrew Kao (Harvard), David Y. Yang (Harvard), and Noam Yuchtman (LSE), or BKYY from here forward. From the paper (bold by me):

We argue that innovation and autocracy can be mutually reinforcing when: (i) the new technology bolsters the autocrat’s power; and (ii) the autocrat’s demand for the technology stimulates further innovation in applications beyond those benefiting it directly. We test for such a mutually reinforcing relationship in the context of facial recognition AI in China. To do so, we gather comprehensive data on AI firms and government procurement contracts, as well as on social unrest across China during the last decade. We first show that autocrats benefit from AI: local unrest leads to greater government procurement of facial recognition AI, and increased AI procurement suppresses subsequent unrest. We then show that AI innovation benefits from autocrats’ suppression of unrest: the contracted AI firms innovate more both for the government and commercial markets. Taken together, these results suggest the possibility of sustained AI innovation under the Chinese regime: AI innovation entrenches the regime, and the regime’s investment in AI for political control stimulates further frontier innovation.

My favorite all-time book is George Orwell’s 1984. (Wrote my college application essay about it.) So the paper’s first conclusion is unsurprising, yet still disheartening: AI does strengthen autocrats’ political control. The panopticon works. BKYY researchers find, for instance, that “weather conditions conducive to protests have smaller effects on contemporaneous unrest in prefectures that have previously invested in public security AI.” Moreover, after public security agencies invest in facial recognition AI technologies, they reduce their subsequent hiring of police staff and shift more existing staff to “higher skilled desk jobs that complement the deployment of AI technology.” So a classic case of tech-disruption where jobs are both automated and complemented.

Second, the researchers look at whether politically motivated AI procurement is good for innovation. They find that receipt of a politically motivated public security contract is associated with significantly greater innovation of commercial software “relative to the receipt of a contract from a non-public security arm of the government.”

Finally, BKYY find that politically motivated public security contracts don’t seem to crowd out “firms’ commercial activities relative to the nonpolitically motivated contracts that provide access to similar resources” and thus distort

the trajectory of innovation. More:

Taken together, these results imply that China’s autocratic political regime and the rapid innovation in its AI sector are not in conflict, but mutually reinforce each other. We do not interpret our findings as indicating that China’s political stability is primarily achieved through AI technology (yet), nor that China’s AI innovation is primarily rooted in political repression. Rather, our findings suggest that a component of China’s coercive capacity is derived from the application of AI technology, and China’s political repression in turn contributes to AI innovation and (potentially) economic growth.

So a really interesting, not to mention clever, paper. It also includes some great history about innovation in authoritarian regimes. BKYY point out the scientific success of the Soviet Union in physics, mathematics, and aerospace and nuclear engineering, achievements that provided huge propaganda benefits. After Sputnik’s launch, Pravda celebrated “how the freed and conscientious labor of the people of the new socialist society makes the most daring dreams of mankind a reality.”

Then there’s the case of the Second German Empire, which “emerged as a powerhouse of science, industrialization, and innovation in the late 19th century.” Imperial scientific institutes, such as the Imperial Institute of Physics “combined the

expertise of German scientists with large amounts of state funding, producing not only

military technology, but also general (even Nobel Prize-winning) scientific and industrial innovations.” (Fear of Germany’s innovation-driven military prowess was so great in Great Britain that it spawned an invasion-themed literary genre that morphed into stories of alien invasion, such as The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.)

A few thoughts here:

It’s interesting that this paper comes out at a time Beijing’s supposed central planning brilliance seems somewhat less wondrous. Lots of headlines with this flavor: “Spooked Chinese brace for ominous winter of shortages, high prices and lockdowns.” At the same time, there are concerns that a recent regulatory crackdown on China’s tech firms will slow growth.

Second, even putting aside recent events, China has a clear productivity problem, particularly when it comes to innovation-driven productivity growth. Being really good at facial-recognition tech isn’t enough. When the Chinese Communist Party loosened its economic control of the economy and allowed market forces to emerge, productivity boomed. And as the CCP has reversed course, that boom has stalled. As my AEI colleague Derek Scissors has noted, “Beijing has long abandoned the pro-market path and shows no true interest in returning to it.” Some numbers from the Economist: “The World Bank calculates that, since 2008, China’s total-factor productivity (tfp) — the amount of gdp growth that cannot be explained by capital or labour — has grown by just 1.1% per year, less than a third the rate of the previous three decades.” More:

The risk for China is that Mr. Xi’s vigorous assertion of statist prerogatives will dull the kind of innovation, competitive spirit and unbridled energy that powered China’s explosive growth in recent decades. The economic policies that helped nurture e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., tech conglomerate Tencent Holdings Ltd. and other global success stories seem to be at an end, say economists inside and outside China. As a result, they say, Chinese companies are becoming less like American ones, which are driven by market forces and depend on private innovation and consumption.

Third, what kind of ecology for discovery, invention, and innovation will there be in an AI-tocracy surveillance state, one that seems ever-more intent on stifling dissent from businessmen, academics, and others? (Even Beijing’s recent attack on “effeminate” male entertainers seems like a bad sign.) Economists Ronald Coase and Ning Wang were onto something in their book How China Became Capitalist when they wrote: “When the market for goods and the market for ideas are together in full swing, each supporting, augmenting, and strengthening the other, human creativity and happiness stand the best chance to prevail, the material and spiritual civilizations march on firm ground, side by side.” That does not seem like the China that Xi is creating.

Fourth, US policymakers should assume the worst, should assume China has developed a socioeconomic system that can challenge the US technologically across an expansive frontier. All government efforts — including taxes, regulation, and investment spending — should be analyzed through an innovation lens. Given China’s rise and totalitarian turn, I’m not sure the leader of the free world has any other reasonable choice.

You argue that, "In the classic Star Trek series, the oppressive Klingon and Romulans have spacedrives and weapons at least as good as those of the free and democratic Federation. Could such authoritarian regimes really occupy and push forward the tech frontier, especially across a range of superscience technologies?"

I'd argue that's actually a misreading of evidence in the series. (Although I'm not sure whether that changes any of your argument in your post beyond the analogy).

There's a bunch of incidents where enemies start out being more powerful, with better weapons, but then lose to the Federation pulling tech tricks out of basically nowhere. The Federation ships are, generally, undergunned compared to other species' ships, but they have way better active and passive sensor arrays, and the science know-how to use them. Arguably, the climaxes of Star Treks 6, 7, 8, and 10, as well as Star Trek (2009) and the Dominion War series in DS9, are all dependent on the Federation outmatching superior enemy forces with better science.

Arguably the Defiant class -- the epitome of the Federation building a warship -- was only needed until the Federation had figured out how to deal with the Dominion's tricks, like shield-piercing energy weapons, suicide run tactics, and the Breen energy dampers. A forward, tough scout like the Defiant matters a lot until you understand your enemy, but once a Federation fleet does, it's all a foregone conclusion.