Many countries around the world have below-replacement fertility rates. And today’s today's guest says it's happening faster than we think, with world population on track to peak around 2060. That’s decades before the well-known UN model projection. What does that mean for the American and global economies, and what can we do about it — if anything? My AEI colleague Jesús Fernández-Villaverde joins this episode of Faster, Please! — The Podcast to discuss those questions and more.

Jesús is a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, where he serves as director of the Penn Initiative for the Study of Markets. He’s also the John H. Makin Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

In This Episode

The speed of demographic transition (1:19)

World population prospects (5:57)

The geopolitics of declining fertility (9:51)

Can public policy reverse demographic trends? (15:09)

Immigration and demographics (23:28)

Below is an edited transcript of our conversation

The speed of demographic transition

James Pethokoukis: A lot of our discussion is going to be based on a paper that you co-authored, “Demographic Transitions Across Time and Space.” When you talk about a demographic transition, you're talking about a shift that countries undergo as they get richer and develop, from a high-fertility/ high-mortality demographic to low-fertility and low-mortality. Is that what you mean by demographic transition?

Why is that something economists study?

Jesús Fernández-Villaverde: Two reasons. First, because we believe that demographics are intimately linked with economic growth. Go back to the beginning of our science: [Thomas] Robert Malthus, one of the very earliest economists, already wrote very coherently about it. And second, because it helps us to think about a long list of policy questions that depend in a crucial way on demographics. When I think about the future of Medicare, when I think about the future of Social Security, those depend crucially on demographics. Understanding demographics is key to having good economic policies.

The key findings of that paper have to do with the speed and the depth of that transition? What are you saying that is different from what people previously believed about the demographic transition?

You're absolutely right: It's about the speed. If you stop any economist or demographer and you ask them what is happening with fertility on the planet, they will tell you it's falling. That's well known. What we add is a twist; we say it's falling much faster than anyone had realized before. And it's falling at a speed that is going to fundamentally transform many of our societies and the planet as a whole in ways that most policymakers are not really taking into consideration. So it's the speed. It's not that it's falling; it is falling immensely fast.

I look at the fertility of the planet as a whole in 2023. According to my calculations, it’s already 2.2. That means that the planet in 2023 is already below replacement rate. Which means that the world population will start falling some moment around the late 2050s to early 2060s. … What I want the listeners to understand is, for the very first time in the history of humanity — humans have been around for 200,000 years — we are below replacement rate in terms of fertility.

People and policymakers may have a general knowledge, but what you're saying is that they're dramatically underestimating how fast that is happening across the world.

Exactly. Let me give you a couple of numbers which personally I think are mind-blowing. Usually, we talk about the replacement rate. The replacement rate is how many children does a woman need to have on average to keep population constant in the long run? And many listeners may have heard the number 2.1. Why 2.1? Because under natural circumstances, without any type of selective abortion, there are around 105 boys born per 100 girls. And a few of the girls that are born are not going to complete their fertility age. So that's why you need a little bit more than two.

In fact, 2.1 is a very good number for the United States. It’s not a good number for the planet. Why is it not a good number for the planet? Because of two reasons. Reason one: selective abortions. You go to China, you go to India — and these are huge countries, demographically speaking — there is a lot of selective abortions. In India or China, you have around 110 kids per 100 girls. Second, because in Africa, another big part of the demographic future of humanity, infant mortalities is still sufficiently high that it makes a little bit of a difference. For the planet as a whole, the replacement rate is not 2.1. It's more like 2.2, 2.25. It’s kind of hard to know the exact number.

So I go to the planet and I look at the fertility of the planet as a whole in 2023. According to my calculations, it’s already 2.2. That means that the planet in 2023 — I'm not talking about the United States, I'm not talking about North America, I'm not talking about the advanced economies, I'm talking about the planet — is already below replacement rate. Which means that the world population will start falling some moment around the late 2050s to early 2060s. Of course, this depends on how people will react over the next few decades, how mortality will evolve. But what I want the listeners to understand is, for the very first time in the history of humanity — humans have been around for 200,000 years — we are below replacement rate in terms of fertility.

World population prospects

That doesn't mean the population's going down now, right? That means the population will be going down a generation from now.

Yes.

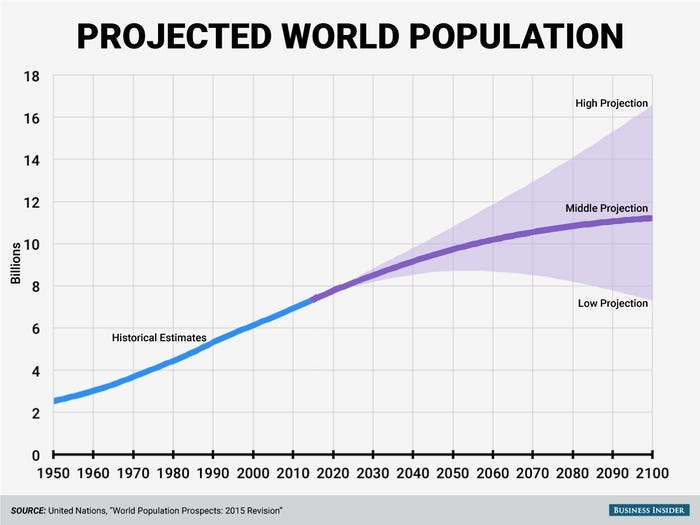

My argument is the United Nations is underestimating how fast fertility is falling. Instead of 2084, I'm pushing this to 2060, let's say. And instead of 9.7, I will say that we will peak around 9.2, 9.1, and then we are going to start falling.

What does that mean for the long-term estimate of peak population? Usually, you hear about the UN forecast and the forecast is usually about nine or 10 billion. So are you saying we will not reach those levels?

Exactly. First of all, let me tell you the United Nations’ population prospects, so everyone knows where I am. The most recent version is 2022. The United Nations forecasts that the peak of humanity will be 2084, and that it'll be around 9.7 billion. My argument is the United Nations is underestimating how fast fertility is falling. Instead of 2084, I'm pushing this to 2060, let's say. And instead of 9.7, I will say that we will peak around 9.2, 9.1, and then we are going to start falling.

And we’ll start declining faster than what the UN thinks?

Yes. Definitely faster. Let me give you a very simple example. The number of births that actually did happen in China in 2022 is what the United Nations forecasted to happen around 2040. So China is running 18 years ahead of the United Nations forecast. And China is a big chunk of humanity. For India, they are also five or six years ahead of the forecast. And if you go country by country, you realize that the United Nations is always behind. If you want, I can tell you why the United Nations is doing this. Basically, their model is running hot. It's forecasting way too many births for what we are actually seeing. And that's why I'm pushing the United Nations [from] 2084 to 2060.

It's a big difference. You're talking about a difference of at least half a billion people, right?

Yes.

That’s a lot. Tell me about the “Rule of 85,” because that's very fascinating. It's kind of a back-of-the-envelope way of looking at how to figure out some of these numbers.

This is something I came up with when I was trying to explain this to undergrads, and I figured out that it’s very easy to remember. Take the United States, take Canada, take Japan: the richest, most advanced economies, so the life expectancy is around 85 years. Imagine that you have a society where you have 1000 people being born every year. Since they are going to be living on average 85 years, in the long run, that's a society that is going to have 85,000 people. If you want to forecast what the level of population of a society will be, just look at the number of births that you have in any given year, multiply by 85, and that will give you kind of a middle-run assessment. It's such a simple rule of thumb. If you want to forecast China: China is slightly below 10 million births; 10 million times 85 — most of us can that in our head — it's 850 million. Well, their population now is 1.4 billion. So there you have a 60 percent reduction. South Korea, they had 240,000 births — I'm quoting from memory, a few thousand up or down — multiply by 85, you have slightly over 20 million. Current population of South Korea: 51 million.

And that’s 20 million when?

It will be 20 million in 85 more years. But in some sense, this is a very optimistic scenario because it's assuming that births are not going to continue falling down, which are probably going to continue falling down because the new cohorts will be smaller. There will be less women having fewer children. In that sense, the Rule of 85, when fertility is going down, kind of gives you an upper bound.

China is looking at a demographic abyss, and unless the Communist Party is able to change that, China is going to be a way less important economy in the middle run.

The geopolitics of declining fertility

It helps to have a lot of people in your country from a geopolitical standpoint. So you're talking about a different world of probably a much smaller China than people are expecting. Maybe relatively, then, a bigger India. And also what does, then, the United States look like? I do realize you don't have all these numbers in front of you either.

I remember many of them. China is looking at a demographic abyss, and unless the Communist Party is able to change that, China is going to be a way less important economy in the middle run. In fact, I'm just finishing a paper with a couple of co-authors where we forecast the economic growth of China. And our main statement using demographics is that the US will grow more than China by the year 2034, because China is going to have such a big falling population. In comparison with India, India has now around 24 million births a year. I told you China is below 10, India is 25 million. So it's 2.5x as many kids per year as China. So in 50 years, the geopolitics of Asia are going to look totally different from what they are now. A lot of people in Washington are very worried about China. I think that they are right to be worried about China until the year 2030, 2035. After 2035, the future doesn't look very bright for China.

Putting aside things that can change, like immigration, what would be your US population forecast?

As you say, the absolute key is immigration. But let's suppose that we go — and it's not that I'm advocating that policy, but as a mental experiment, a thought experiment — let's suppose that we have perfectly closed immigration, zero immigration from now on. The US right now is 335 million, so we will probably peak at 340 million and then start falling. In fact, the US population that has both parents born in the US is already falling.

What might change this forecast, either up or down? One thing you mentioned in another piece that you wrote is people's religious affiliation. Whether they become more religious, less religious, that seems to have an impact on their fertility rate and birth rates.

Yes, exactly.

And that can change.

That can change. For instance, let me give you a very simple example that a lot of people may relate to. When Ireland was partitioned and the 26 counties in the south of Ireland became the free state of Ireland, and the six counties in the north stayed as Ulster or Northern Ireland, Protestants were around 65 percent of the population and Catholics were around 35 percent. That's why they didn't want to join the free state of Ireland. In Northern Ireland, probably Catholics are going to become a majority. Why? Because Catholics in Ireland for the last 80 years have had a little bit higher fertility.

Why is this going to become so much more important? Let me give you a very simple example. Let's go back to 1950 and let me, in a very crude way, separate families between secular and religious. A secular family, let's say, has 2.5 kids. And a religious family, on average, has three kids. The difference is 0.5, but the base, 2.5, is sufficiently high that it doesn't make much of a difference. Now fast forward to 2023. The secular family is having one kid; the religious family is having two. First of all, the religious families have also reduced their size, but they have reduced their fertility less than seculars. And because the secular base now is so small, now we are talking about huge differences.

The question, of course, over time is going to be, how much of this religiosity will be transmitted intergenerationally? It's the case that the sons and the daughters of religious families are also going to be religious or not. But let's assume there is some persistence. That basically will tell you that in 200 years, the composition of the US population will be extremely different. And in fact, this is not a crazy point. Most historians of what is known as late antiquity — late antiquity goes from around 300 in the current era to around 700 in the current era — argue that conversions to Christianity stop around the year 370, 380. I'm talking about Western Europe. Basically what happens over the next 300 years is that Christians have a higher fertility than non-Christians. And by the early 700s, there are just not that many non-Christians left in Europe, and Europe has become a totally Christian continent. So these things happen. Small differences in fertility, you run them for 200 years and it has a huge difference. And again, going back to my point, Northern Ireland is a very different place today than 100 years ago just because Catholics have a little bit more kids than Protestants.

Aggressive policies like child subsidies, making it easier to reconcile family and work, maternity leaves, etc. can push you back to 1.7, 1.8. You are never coming back to three. You are never coming back to four. Can public policy reverse demographic trends?

Something else that could change is public policy. In countries which are already experiencing these drops, they’re giving bonuses to get people to have more kids. And there's a variety of sort of subsidies to encourage… Do those policies work? My baseline is that they probably really don't work. Maybe people have kids sooner than they would otherwise. Do we know of policies that actually have any kind of significant change on the number of kids people have at least in the rich countries?

First of all, let me be absolutely open that the jury is still a little bit out because, as you say, maybe what is happening is that people are just changing the moment where the kids are born. My reading of the evidence is that you make a little bit of an impact. Right now, think about countries like Spain or Italy where fertility rates are around 1.2, which is absolutely horrible. It's like a reduction of half of the size of the population in each generation. Aggressive policies like child subsidies, making it easier to reconcile family and work, maternity leaves, etc. can push you back to 1.7, 1.8. You are never coming back to three. You are never coming back to four. The point I have argued to policymakers is if you are in a society where the fertility rate is 1.8, you can handle a gently decreasing population. What you don't want to be is in front of a demographic abyss. So policies, in my reading of the evidence, help you to go from disaster into gentle decline. And I think the evidence supports that that can be achieved.

What do we know about societies that undergo a demographic decline? I imagine the past when that's happened, it's been because of war and disease, not because of choices people make voluntarily. There's been some sort of shock. Do we really have a good feel for what that looks like, when a country undergoes demographic decline, not because of disaster but because of just the choices people make, whether because of religious reasons or the cost of childcare or whatever?

We don't. We have never been there. I have written a piece with what I think are educated conjectures. What type of educated conjectures [do] I have? First of all, it's going to be a society that is way less dynamic. I'm a little bit older than I used to be, and I already realize that for me to adopt new technologies now is much harder than when I was 10 years younger. As the average person in society becomes older and older, you are just going to have societies that adopt fewer new technologies, you have fewer new entrepreneurs, etc.

For instance, there has been a lot of discussion that in the US there are now way less new businesses than 10, 15, 20 years ago. And there is a great economist at the University of California at LA, Hugo Hopenhayn, who has I think very convincingly demonstrated that this is completely driven by the fact that we have less 25-year-olds. Most new firms are created by people in their 20s, late 20s. We have now fewer people in their late 20s. And what he actually shows is that the percentage of people in their late 20s that create firms is the same as before. But there are less of them, so you are going to have fewer new firms.

We are going to be also societies that somehow lose a little bit of the sense of the future, because everyone tends to be very old. And then the third point that I conjecture — and this is something that we really, really want to keep in mind — is that drops in population are not going to be uniform across space. What I mean by that is, let's suppose that as I was mentioning before, things continue in the way they continue now in South Korea for another 50 years. So South Korea is going to lose 30 million people. Those people are not going to disappear from Seoul, from the capital; they're going to disappear from rural areas. And then what do we do with those rural areas? There is going to be a moment, and you already see that even in the US, but in a lot of places in Western Europe, population in a county starts to fall down, fall down, fall down.

And you know what the real problem is? One day they close the supermarket. And it's not because supermarket owner is evil. It's just because to run a supermarket, you need enough people. And suddenly there is not enough people in the county to have a large supermarket. And once you don't have a large supermarket in the county, life becomes very hard, because the only thing you have is a convenience store. So people move out. Even people who want to live in the small rural counties move out of the rural county because there are no services in the rural county anymore. I think about, who is going to keep the universities in a small rural areas open? There is just not going to be enough people to go to these colleges. And how do you go to your community and tell them that you are closing the local campus of your biggest state university just because there are not enough kids?

At least a few of the listeners are already thinking of the film Children of Men. Are you familiar with it?

I actually am not.

The premise is that for some reason 18 years ago, 18 years previous, women over the course of like a year just stopped having kids. And the movie begins where the youngest person alive ends up being murdered. He's an 18-year-old. It's a world where nobody's having kids and society's beginning to fall apart. It's like people have nothing to live for. They're already trying to gather up great works of art and preserve them. They don't know for who. It just seems like a society that's winding down.

Let's get back. Mortality could change, of course.

Yes.

CRISPR, all kinds of genetic editing — you can't really predict where technology will go, but that is something that could potentially change. Or even artificial wombs, maybe that will change people's choices as well.

Fair enough. Let me just tackle the issue of mortality. Remember the Rule of 85? You can change it to 90, to 95, 100. You know, 100 will be very easy because you just put two zeros. Let me go back to China. I told you 10 million births a year; now apply a rule of 100, that will be 1 billion. They are still losing 400 million. And do we really think that increases in medical technology can push mortality much later than 100? I'm not an expert, but from when I talk with people who are a little bit more knowledgeable that I am, they tend to be skeptical. In fact, I have been talking with economists who have been looking at mortality and the changes in mortality in the US and other advanced economies. Most of what modern medicine does for you is increasing the quality of life over the last years. It used to be the case that you would see someone in his 70s and he will be old and in very bad shape. Now, you're in pretty good shape until three days before you die. So I think that a lot of what medicine is going to do is not increase our life expectancy that much; it’s just about making our quality of life better. As a piece of a personal anecdote, if I may, both my wife and I are economists, which means that we have long sessions at home discussing investment portfolios and retirement accounts. And we include equations — I know that most of you probably don't have discussions with whiteboards at home and covariances of investment — but the age that I use for my own forecast of my own life is 90. I don't use more than 90, so at a personal level, I don't forecast myself living on expectation over 90 years old.

Immigration and demographics

One solution that's not a technological solution is immigration. But I would think there is a limit — even for the most pro-immigration country — to how many immigrants. It seems like it's not really a plausible policy for most countries, maybe for the United States more than others, but even here there's limits.

Yes, of course. First of all, every time I talk about immigration, I remind people I'm an immigrant myself, as you can probably tell from my funny accent. So it's not that I'm against immigrants. What I tried to point out in something that I wrote is, look, I was mentioning that South Korea is about to lose 60 percent of their population. That will mean that if you want to keep population constant, you will need that 60 percent of people living in South Korea who are not of Korean heritage. Have we ever seen societies that undertake such a deep demographic change in a couple of generations? Can a political system digest that change? I'm quite skeptical. One thing is to bring 10 percent of your population, 20 percent of immigrants. A very different thing is to have 60 percent.

Second point: I mentioned before that the planet as a whole is going to start losing people. And as far as we know, the net immigration to the planet is still zero. Maybe like in Men in Black there are some people coming from outside. But let's say the US in 2040 is still bringing immigrants from some developing economies, it means that demographic problem of these developing economies is going to become even more serious.

So let me give you a concrete example. If I were the minister of finance of Brazil, I would not be able to sleep at night. Brazil will probably start losing population around 2030, 2032, if not earlier. Who's going to migrate to Brazil? Brazil is still losing population. The best and the brightest of Brazilians move to the US or to Europe. You go to any good US university, and there's a lot of top Brazilian students and researchers. Brazil starts losing population, which immigrants do you bring? Who's going to move to Brazil?

Another country that, believe it or not, will probably start losing population maybe in another 20, 25 years are all Central American republics. Who's going to migrate to Guatemala? So what do you do then?

More likely that even more so people who have possibilities, who could get a job in an advanced economy, they will leave.

Exactly. So you're going to really, really be in a very tight spot. The immigration to me sounds really like I'm a US person, or I'm a German person, I'm thinking about this from a European or a North American perspective. I want the listeners to understand this is for the planet as a whole. And by the year 2055, every immigrant I'm gaining is someone else that is losing an immigrant.

But let's suppose that immigration stays at a historical level, a historical average. The US is not going to be in a very tight spot, demographically speaking, in 2040. China is going to be on a very tight spot, and that's going to really be a game changer. Which goes back to my point before about why I'm not worried about China taking over the world in the year 2050.

If you are a country who is able and has a history of accepting immigrants, it sounds like on a comparative level, that is really to your advantage. And if you think not only the size of your country, but the quality of your workforce is important, to me, you're making a case that this would be a big plus for the United States overall from a geopolitical, geo-economic position — relatively.

Sure. Coming back to our discussion about China versus the US, I think the US is still going to attract immigrants. How many immigrants we want to attract — and I say “we” now because I'm naturalized, so I can say we — how many immigrants we want to attract is a discussion we can have. But let's suppose that immigration stays at a historical level, a historical average. The US is not going to be in a very tight spot, demographically speaking, in 2040. China is going to be on a very tight spot, and that's going to really be a game changer. Which goes back to my point before about why I'm not worried about China taking over the world in the year 2050.

As I was mentioning in a previous answer, if somehow we avoid a conflict with China by the year 2030, in some sense, the war is won. It’s just an issue of waiting 10 years, handling this situation. Because China will really, really need to do something serious with their economy and their political system. Now, something that can happen is that China, you know, starts forcing people to have a lot of kids. What I will [remind] listeners is some very basic facts of nature: Even if the Chinese government starts forcing everyone to have kids, it will take nine months — and one night, I guess — and then once the kid is born, it takes, what, 22 or 23 years before this person completes college. And if we want these people to be top researchers, etc., they need to go to graduate school. It’s 20 years. Think about it in this way: If we are thinking about the top researchers among the cohort that is being born today in 2023, these people are not going to be researchers until 2051. Demographics has this enormous momentum; things that we decide today do not really show up until 30 years later. And by the way, that's one of the reasons I think that a lot of the demographic policies and a lot of economists are not very good, because most politicians do not think 30 years ahead.