🇺🇸 2076 or Bust: What will the US and world look like on America's Tricentennial?

Goldman Sachs sees both China's and India's economy overtaking America's

➡ First things first: I’m happy to be back writing after a month away. That means back to the regular schedule of three essays a week (one with no paywall), a weekend recap, and a regular podcast (with transcript). To thank my free subscribers for their patience, I am offering a special deal all month. See the Big Blue Button Below!

First a caveat: Everything in this essay assumes a) the United States doesn’t descend in Civil War 2.0, b) Vladimir Putin doesn’t press The Button, and c) there’s no reason for fresh supervolcano concerns (you people know who you are) over recent news that there’s more magma below the Yellowstone Caldera than previously thought.

Now, with that out of the way, let’s fast forward to the 2070s, specifically to 2075, a time when Americans should — hopefully — be excitedly gearing up the for coming Tricentennial in 2076. The economic state of America and the world in that year is the subject of a fascinating new report from megabank Goldman Sachs, “The Path to 2075 — Slower Global Growth, But Convergence Remains Intact Research” by Kevin Daly and Tadas Gedminas. It’s been more than a decade since GS last did this, as Daly and Gedminas note:

In the period since our 2011 projections, the global economy has been buffeted by a number of secular challenges and economic shocks: disappointing productivity growth in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), a rise in global protectionism, the Covid-19 pandemic and, more recently, the war in Ukraine. Despite these headwinds, most of the key features of both our 2003 and 2011 projections have remained intact. However, others now need to be re-visited.

Daly and Gedminas focus on four key themes and trends:

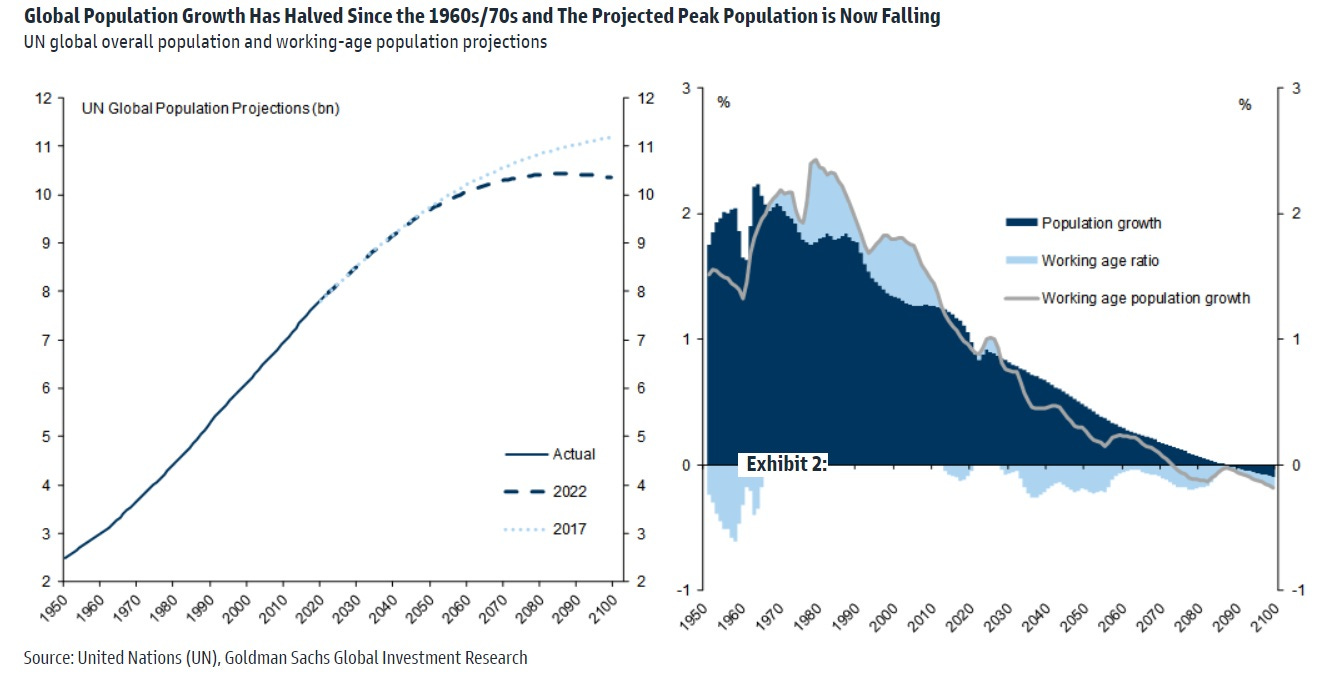

1. “Slower global potential growth, led by weaker population growth.” The economists see global growth averaging 2.8 percent between 2024 and 2029, and then trending lower to below 2 percent by 2075. That’s down from 3.2 percent in the decade after the GFC and 3.6 percent in the decade before. To a great extent, the passing of Peak Global Growth is a story of demographics:

Global population growth has halved over the past 50 years, from around 2% per year to less than 1% currently, and UN population projections imply that it will fall to close to zero by 2075. While some of this slowdown had previously been anticipated, population projections are also being revised lower (the global population is now expected to peak at around 10 billion people, having previously been expected to rise to more than 11bn). This is a ‘good problem’ to have, in that global population control is a necessary condition for long-term environmental sustainability. Nevertheless, this adjustment to weaker population growth and ageing populations presents a number of economic challenges (most notably, from rising healthcare and retirement costs).

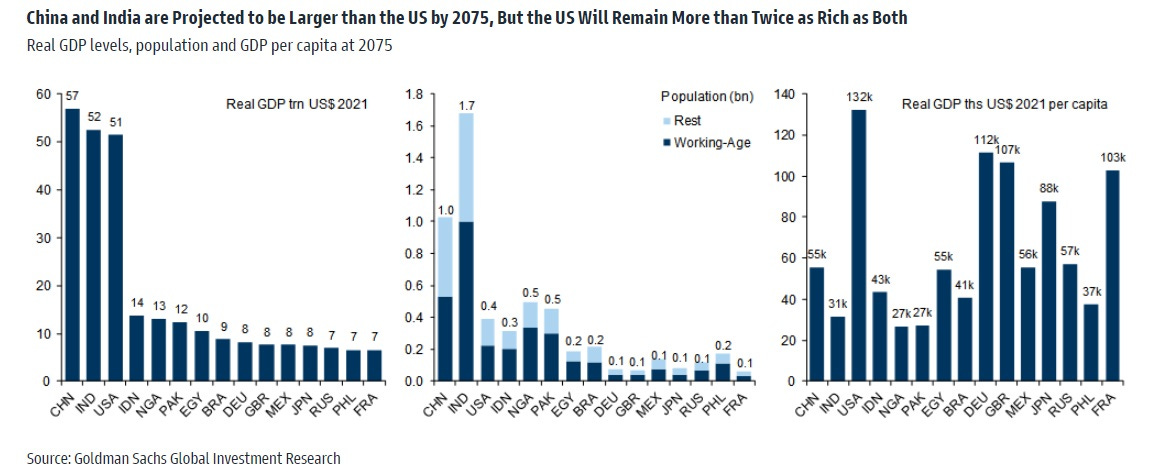

2. “Emerging market convergence remains intact, led by Asia’s powerhouses.” While global growth has slowed and will continue to slow, EM growth has outpaced and will continue to outpace that of developed economies. Daly and Gedminas: “China, India, and Indonesia all slightly outperformed our [2011] forecasts, while Russia, Brazil, and Latin America more generally significantly underperformed our projections. As a consequence, we expect that the weight of global GDP will shift (even) more towards Asia over the next 30 years.” It’s this trend that supplies probably the newsiest aspect of this report. Their projections imply that China, US, India, Indonesia, and Germany will be the world’s five largest economies by 2050, with China, India, US, Indonesia, and Nigeria taking the top five spots in 2075. They see China overtaking the US around 2035, with India catching up by 2075.

3. “A decade of US exceptionalism that is unlikely to be repeated.” Maybe I’ve been too gloomy about the American economy, even though I’ve never descended into the absurd “failed state” talk of some. Daly and Gedminas: “Uniquely among large, developed economies, the US slightly outperformed our long-term real GDP growth projections over the past decade. Moreover, with the Dollar also appreciating sharply over this period, the relative USD value of the US economy significantly outstripped our expectations.” That said, the economists see US growth potential as significantly lower than China and India, especially the latter. And as for the former, its growth edge fades as the decades go by. “US potential GDP growth is expected to be materially faster than China's at that horizon, as a result of its better demographic outlook.” Here are real GDP growth projections (market FX weighted) for the world’s major economies by decade:

Real GDP Growth Projections for Major Economies by Decade

4. “Less global inequality, more local inequality.” The report highlights an important but seemingly little-known fact: The past three decades of globalization-fueled growth have resulted in a more equal distribution of global incomes by making poorer countries get richer faster than already rich countries.

And what might go wrong with this scenario, setting aside US civil war, a nuclear exchange, and Yellowstone blowing its top? There are the two biggest risks to continuing growth and income convergence identified by Daly and Gedminas:

First, the risk that populist nationalism leads to increased protectionism and a reversal of globalisation. Populist nationalists have gained power in several countries and the supply chain disruptions during the Covid pandemic have resulted in an increased focus on on-shoring and supply chain resilience. At least to date, this has led to a slowdown rather than a reversal of globalisation, in our assessment. However, the risk of a reversal is clear. Globalisation has been a powerful force in reducing income inequality across countries but, to ensure that it continues to do so, greater efforts need to be made to share its benefits more equally within countries.

Second, the risk of environmental catastrophe presented by climate change. We reject the view that economic growth and environmental sustainability are incompatible – many countries have been able to 'de-couple' economic growth from carbon emissions, so there is no practical reason why this should not be achievable for the global economy as a whole. But achieving sustainable growth requires economic sacrifices and a globally coordinated response, both of which will be politically difficult to achieve.

Oh, I have some thoughts on all this:

First, there’s plenty in this forecast that would give future Americans good reason to celebrate the country’s Tricentennial year. Although the American economy might only be the third largest economy by then — and not lagging by much, really — the average American, at a per capita GDP of $132,000 (versus $70,000 today) would be more than twice as rich as the countries above it, China and India.

Second, these forecasts are based on current trends, from population growth to capital investment, with a bit of country-specific historical performance mixed in. They don’t, unsurprisingly, assume significant technological disruptions of the sort I frequently write about in this high-value newsletter. It assumes there is no Next Big Thing. There’s no assumption or speculation that AI will be a transformative General Purpose Technology, that highly capable humanoid robots will boost labor productivity, that CRISPR advances will solve many chronic diseases and extend our healthspan, that energy breakthroughs will power all sorts of radical innovations, or that the benefits of an expanding orbital economy will be immense. Nor, for that matter, does this forecast assume a significant failure by Chinese state capitalism to generate higher innovation-driven productivity growth. The Chinese economy might never catch the American economy.

Third, given the previous point, there’s no way we should accept a future where the American economy is growing at 1.2 percent a year, which will feel like no growth at all. Look: This a Forecast of a Future that Could Be not Must Be. As Ebenezer Scrooge asks the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come in A Christmas Carol, “Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?" And after the Ghost points down to a gravestone, Scrooge continues, “Men's courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead," said Scrooge. "But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change."

We have a choice here. America must depart from the course we've chosen this far and pick a new one. We have chosen to invest too little, regulate too much, trade too little, and restrict immigration too much, among other mistakes. We can make different choices. The best time would have been decades ago. The second best time is ASAP.