⚾ What 'Moneyball' got wrong: Pro baseball scouts can teach us a lot about automation and technological unemployment

Using data and technology + old-school experience and intuition seems to be the winning combination

When you consider automation’s impact on jobs, perhaps you think about long-haul truck drivers and self-driving 18-wheelers or maybe fast-food cashiers and touch-screen kiosks.

But I think about pro baseball scouts. Perhaps the most memorable scene in the 2011 baseball film Moneyball (based on the book of the same name) is when Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane (played by Brad Pitt) — trying to install a more data-driven approach to player evaluation — holds a meeting with his old-school scouting department. The issue at hand: the loss of three of the team’s best players to free agency. As the various scouts, all older men, mention possible replacements, they offer evaluations that are subjective, even impressionistic, rather than objective and empirical:

Artie: I like Perez. He swings like a man.

Keough: He swings like a man who swings at too much.

Artie: There's some work needs to be done. I admit it. He needs to be reworked a little. But he's noticeable.

Grady: He's notable?

Artie: No, he's noticeable. You notice him.

Keough: He's got an ugly girlfriend.

Barry: What's that mean?

Keough: Ugly girlfriend means no confidence.

Barry: Alright. That's true.

Pittaro: I agree with Art. I like the way he walks into a room.

George: Passes the eye candy test. He's got the looks. He's ready to play the part. He just needs some playing time.

Keough: I'm just saying, his girlfriend's a six.

At which point, Beane, in frustration, raises a book above the table and drops it with a dull thud on the conference table. He then proceeds to explain his new data-driven approach, one that cares about modern statistics such as On Base Percentage rather than the attractiveness of player girlfriends. Afterward, the team’s head scout tries to get through to Beane, one on one:

You don't put a team together for the computer, Billy. Baseball isn't just numbers. It's not science. If it was, then anybody could do what we're doing. But they can't because they don't know what we know. They don't have our experience and they don't have our intuition, okay? … There are intangibles that only baseball people understand. You're discounting what scouts have done 150 years.

To which Billy responds: “Adapt or die.”

A Moneyball approach to player scouting and team managing has yet to lead to a World Series win or even a championship appearance for Beane and the notoriously cheapskate A’s. But it did for the Houston Astros. They won the World Series in 2017 and were noted for their data analytics (and later for their cheating).

Yet the Astros also fielded a traditional scouting department “of between 45–60 total scouts every year from 2010–17, on par with industry standards,” according to a recent Baseball America story on the team. And with good results. Many of the key players during that championship run — including Carlos Correa, George Springer, Alex Bregman, and Lance McCullers Jr., — were drafted and developed in house.

But after the 2017 World Series, the Astros changed course. They decided to make scouting more data- and video-based, using far fewer scouts. They went more purely Moneyball. As Baseball America reports, the Astros had just 19 total scouts by the start of the 2019 season, about one-third of what they had three years earlier. This remaining group often had to cover huge territories such as “Los Angeles to the Canadian border or Dallas to the Dakotas.” There wasn’t much time to evaluate any one player’s on-the-field performance, much less get a sense of his character and personality. From BA:

In one instance, the organization was unaware of widely known behavior concerns about a draft prospect because it did not have an area scout dedicated to the region. The team only learned of the concerns after they drafted the player, when scouts from other teams texted their Astros counterparts incredulously asking them what they were doing. “There was just not enough hours in the day, not enough manpower to get deep into the background and learn who the kids are (and) do home visits,” said Astros special assignment scout Gavin Dickey.

Then in 2020, the Astros got a new GM, James Click, previously with the Tampa Bay Rays. The Rays were a team with a great reputation for using data in player evaluation, but also valuing traditional scouting, employing “one of the largest scouting staffs at all levels — amateur, pro and international — and blending their data with copious amounts of in-person evaluations,” according to BA. Since Click’s hiring, the Astros have doubled their scouting department and are eager to keep adding.

Video, data and other technologies remain a significant part of the equation, but they are used to complement or assist, not replace, scouts on the ground. “Our scouts have shown an amazing ability to use that information and take it into their reports and their assessment of the player, and so in some sense what we want them to do is help us interpret a lot of that information that we get from the new technologies,” Click said. “But at the same time we don’t have technology that can figure out what is in a kid’s work ethic (or) what is in his makeup. Is this the kind of kid who gets out there to the low minors and can work his way through it, grind his way through? Making sure that we understand the person who we’re drafting and how they react to pro baseball and how they will carry themselves as a professional representative of the Houston Astros organization is a huge focus for our guys.”

A trained economist couldn’t have better described the process of technology complementing labor rather than merely replacing it. Broadly speaking, some technologies are job displacing. They displace workers from the tasks they were previously performing. A classic example is the Jacquard Loom, a power loom invented in 1801, which greatly automated weaving (as well inspiriting the eventual invention of punch-card computers.)

Another example is when between 1920 and 1940, AT&T adopted mechanical switching technology in over half of the US telephone network, replacing manual operation. As economists James Feigenbaum and Daniel P. Gross write in the just-revised working paper “Answering the Call of Automation: How the Labor Market Adjusted to the Mechanization of Telephone Operation,” this automation caused “a large negative shock to local labor demand for young, white, American-born women, with the number of young operators dropping by upwards of 80% — a near-total collapse in entry-level hiring in one of the country’s largest occupations for young women. Around 2% of jobs for this group were permanently replaced by machines upon the flip of a switch.”

But technology can be complementary or enabling to workers as well as displacing. Search engines, spreadsheets, and databases are examples of information technologies that augment human capabilities or create new things for them to do. An early example: The Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient astronomical calculating machine probably built around 140–100 B.C., that could predict solar eclipses and organize the calendar into the four-year cycles of the Olympiad, forerunner of the modern Olympic Games.

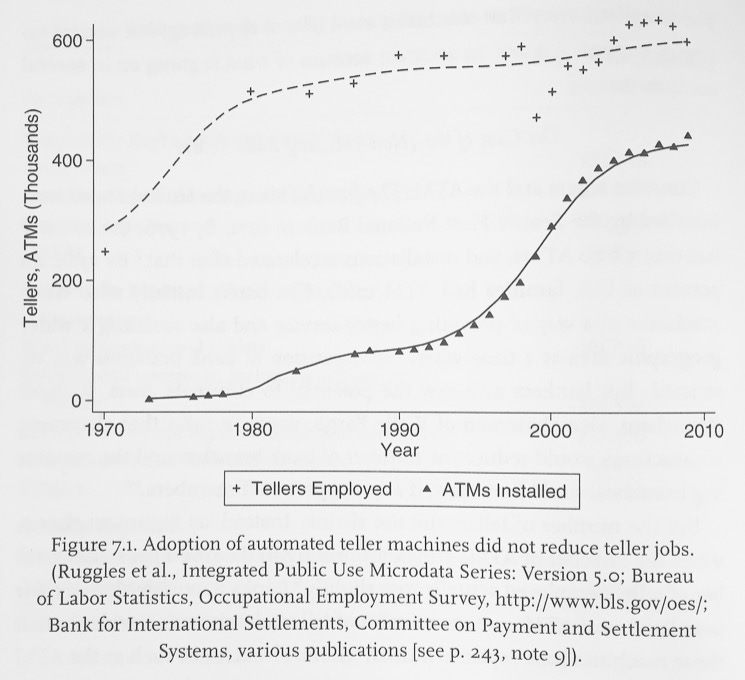

Or consider automatic teller machines. ATMs took away a whole range of tasks that bank tellers were performing. But now banks devote more resources to higher-value activities such as financial planning advice. (It also became cheaper to open bank branches so bank teller employment actually increased .) In the case of baseball scouts, it would not surprise me if data and video make performance evaluation easier, thus making scouts with strong interpersonal skills even more valuable.

I also think about how a computer-assisted chess player can often play better than either a human or software program alone. A 2021 Wall Street Journal piece explains how world champion Magnus Carlsen uses move-recommendation engines:

But here’s the twist: the most lethal use of computer-based analysis isn’t to find something that only the machine can see. It’s figuring out what it sees and dismisses that might still be useful. The dream of any computer-savvy chess player is to discover a string of moves that an engine doesn’t necessarily favor, yet taps into a line that their opponent hasn’t prepared. … In any given situation, the engines might recommend any number of moves and suggest that they are all relatively equal. Those are the obvious ones to study. But by playing a more obscure move — perhaps even one that the computers suggest is disadvantageous — Carlsen thrives by throwing his opponents into that unfamiliar territory.

Thinking about how a machine or robot can replace workers is simpler than imagining how technology can make workers more productive or even create new things for workers to do — with the result being higher wages and more jobs. It’s probably why so many of us fear the job impacts of new tech despite a long history of such fears failing to materialize.

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples of those interviews:

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy