🌐 The new book 'Streets of Gold' shatters myths as it makes the case for a nation of immigrants

Also: My Q&A with co-author and Princeton University economist Leah Boustan

Streets of Gold: America's Untold Story of Immigrant Success by economists Ran Abramitzky (Stanford University) and Leah Boustan (Princeton University) is a book that I’m sure is necessary — but far less sure is sufficient for these polarized times. No doubt, the current debate in America about immigration could use a common set of agreed-upon facts. And if you have an open mind to the hard evidence, you’ll find Streets of Gold tremendously valuable. I know I do.

In addition to highlighting what other economists currently think they know about immigration, Abramitzky and Boustan present their own fascinating findings from a novel research approach. By automating searches on the genealogical website Ancestry.com, the researchers were able to digitally follow millions of immigrants through time as they climbed the economic ladder and integrated into American society. (In addition to the fascinating data, there are also lots of great immigrant stories. Streets of Gold would make a compelling documentary.) Among the insights and myth-busting found in this marvelous little book:

Upward mobility, just as in the past. Immigration policy has changed a lot over 100 years. Even so, immigrants today move up the economic ladder at the same pace as did European immigrants in the late 19th and early 20 centuries. It has always been a slow climb, far slower than our “rags to riches, ASAP” national mythology would have us believe. That said, the evidence suggests no reason to fear that “today’s immigrants from non-European countries like Mexico and El Salvador will not be able to replicate the past successes of European immigrants.”

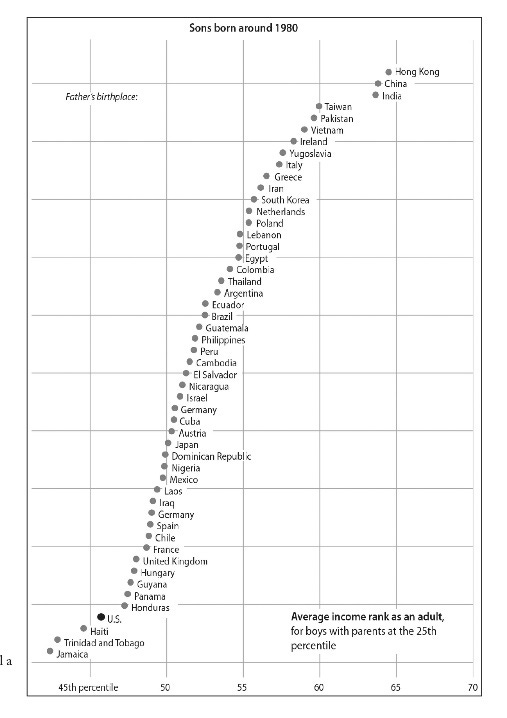

The kids are all right. “Background is not destiny.” The researchers find that “children of immigrants from nearly every country in the world are more upwardly mobile than the children of US-born residents who were raised in families with a similar income level.” So an apples-to-apples comparison here. Again, this is true even with kids whose parents come from quite poor nations, including Central American countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, Nigeria in Africa, and Laos in Asia. “The children of immigrants do typically make it in America. And it most often takes them only one generation to rise up from poverty.”

They’re just like you and me. Whichever metaphor you prefer — America as a melting pot or a salad bowl — Abramitzky and Boustan find that immigrants “shift toward the behaviors of the US born at much the same pace in the past and the present.” Take your pick of cultural signifiers that show an immigrant to be a “real” American: learning English, marrying US-born spouses, leaving immigrant neighborhoods, adopting American-sounding names. “Immigrants and their descendants participate in a broadly shared American culture and adopt deeply felt identities as Americans.”

Immigrants mean jobs and growth. Econ 101 is important, but you have to know more than what’s taught on the first day of class. The impact of immigration on jobs and wages might be negative in both cases if there were a fixed number of jobs, which obviously isn’t the case. Rather, “by contributing to innovation and starting new businesses, immigrants often create new employment opportunities for others. … And immigrants need new housing and consumer products themselves, all of which helps put Americans to work. … The evidence, however, does not support the idea that immigrants lower wages of less-educated US-born workers overall.” Who loses? Some workers who do the same kinds of jobs as immigrants, and this often means other recent immigrants.

A natural experiment in immigration restriction

That’s the 30,000-foot view. Let me briefly drill down into one part of the book. In the 1920s, Congress enacted immigration quotas that favored immigrants from northwest Europe. Those restrictions created an inadvertent natural immigration experiment. Consider Ohio’s then two most populous cities, Cleveland and Cincinnati. At the close of the 19th century, the two cities had similar populations, but only Cleveland had a community of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Despite the immigration quotas of the 1920s, cities like Cincinnati continued to receive steady inflows of northwestern European migrants. But after the border closed, Cleveland saw a significant reduction in inflows of southern and eastern European immigrants.

The results of the natural experiment? Abramitzky and Boustan (bold by me):

In the short run, workers living in cities like Cleveland may have enjoyed higher earnings. But soon enough, firms found ways to avoid paying these higher wages. These firms replaced European immigrants with two groups of new workers: immigrants from Mexico and Canada (countries not subject to the quotas) and US-born workers who moved in from other areas, including rural-to-urban migrants. Many of the new arrivals were young men, lured into the city by the new job openings. Moreover Black workers in the South began migrating north in large numbers only after the border restrictions choked off immigration from Europe. … In rural areas, the loss of immigrants as farm labor did not open up jobs for US-born workers. Instead, immigrant workers on farms were replaced by machines, rather than by new pools of workers from elsewhere.

Thus, in both cities and rural areas, even the most sweeping immigration restriction in American history had only mixed effects on the existing workforce. … But the benefits to workers were far smaller than one might think because employers are highly adaptive. … Today, the idea of substitutions remains the same. If the United States stopped admitting foreign-born doctors, for example, many of the diagnostic services might be outsourced to physicians working remotely from overseas. And without immigrants to hold factory jobs, firms might invest in expensive robotic arms or other automation technology. The immigration restrictions of the 1920s teach us that the idea of closing the borders to aid American workers is too simplistic for the messy complexity of the real economy.

Short version: Immigrants today join the American Project, both economically and culturally, and contribute to it just as immigrants always have. (Please also check out my recent essay “The amazing success of 'Asianomics' in America — and what we should learn from it.”) All Americans should welcome these findings.

Indeed, my read of things is that at least some anti-immigrant types may be prepared to mostly concede the above economic points. (Recall Stephen Bannon lamenting the number of Asian immigrant CEOs in Silicon Valley.) In doing so, they are really, in effect, starting to say the quiet parts out loud: Opposition to immigration is about Down Wing nostalgia for a whiter, more homogenous America — even if it was a poorer America in all sorts of ways. Moreover, if reducing immigration today results in an America with less growth and opportunity in the future, so be it. Although Streets of Gold doesn’t make this argument or delve into the darker reasons why some oppose immigration, it’s hard not to reach this conclusion after a good-faith read of the economic evidence. And that evidence is powerfully persuasive. Immigrants better themselves, their kids’ futures, and their newfound home.

Q&A: A conversation with Leah Boustan, co-author of Streets of Gold: America's Untold Story of Immigrant Success

Leah Boustan is a professor of economics at Princeton University, where she also serves as the director of the Industrial Relations Section. Her research lies at the intersection between economic history and labor economics. Her first book, Competition in the Promised Land: Black Migrants in Northern Cities and Labor Markets examines the effect of the Great Black Migration from the rural south during and after World War II. Professor Boustan was named an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow in 2012 and won the IZA Young Labor Economist Award in 2019.

Pethokoukis: How important is it to look at how second-generation — or the US-born children of immigrants — Americans are doing when evaluating immigration policy?

Boustan: It’s really important to take the long-run view when thinking about immigration policy. If the first-generation immigrant parents are not earning very much because they come from poor countries — maybe a country where you can’t even go to high school very easily — and they come to the US and do low-paid work, is that going to be destiny for their kids? [Will they] also be in low-paid positions and the next generation after that and so on? And so it’s really important to see how the children of immigrants are doing. They’re raised in the US. They’re going to US public schools. Are they moving up into the middle class?

Are the children of immigrants moving up into the middle class?

That was one of the most surprising things that we found in the data. So we’re talking about immigrants today from around 45 sending countries, countries where we have enough data where we can really dive into it. And if you’re talking about immigrants where the kids are being raised below the median, all the way down to the 20th and 25th percentile of the income distribution, are the kids making it to the median, are they making it to the middle class? And the answer is yes, for almost every sending country in the world today.

The book does a great job talking about the positives of immigration, from the effects on innovation to the effects on culture. Who are the losers and what are the trade-offs?

The first trade-off is in the labor market. There are going to be some workers who are doing the same kinds of [work] as immigrants, particularly, if you’re talking about low-paid jobs. So other people working in agriculture, child care, elder care, landscaping, construction, that sort of thing. And who are those workers? Most of them are recent immigrants themselves. So maybe an immigrant who came here five or 10 years ago. And it’s those groups that are going to face some competition in the labor market from new immigrants coming in. In terms of other trade-offs, there are cultural positives and negatives. From my perspective, I like living in a city where I have a whole range of ethnic cuisine so I can go to restaurants of different kinds. Other people might not like that. So there’s going to be some differences in tastes about what immigrants bring and whether we like it or don’t like it.

There has been some research showing that in more diverse societies there’s less trust, and that might manifest itself in less support for the welfare state. Maybe you’re okay with someone getting a check if they’re a lot like you, but if they’re not like you, maybe you don’t like it so much. Is that a legitimate concern?

Are immigrants going to remain different from the US-born indefinitely? Their kids and their grandkids, are they also going to look different? Both for the immigrants themselves and for their kids, they become increasingly more like the US-born as time goes on. So immigrants might come not speaking English, watching a totally different set of media, listening to different music, having different political views, and so on. And over their own lifetimes, they start to transition and move towards the kinds of tastes of the US-born. And the kids all the more so. Basically, we shouldn’t think that there’s the US-born and there are immigrants, and they’ll remain different forever. If we’re worried about differences persisting and causing trouble, causing strife and rifts in society, underlying that is an idea that immigrants will always remain different — that’s just not true.

The chapter on assimilation was the one that I found the most eye-opening. I kind of assumed that immigrants today were not assimilating as fast as immigrants from the early part of the 20th century, and that maybe we needed more assimilation programs for immigrants when they came to this country or more programs in schools. But that doesn’t seem to be the case.

That surprised me the most, too, because I really bought into the myth that 100 years ago immigrants came from Europe and they weren’t that different culturally from the US-born, and that today we’re trying to absorb immigrants from 100 different sending countries. In the past, there was some concern about Catholics vs. Protestants, and now we’re talking about like 20 different world religions, so it was inevitably going to be more challenging. But immigrants are making major efforts now, as then, to become American.

How do immigrants benefit from being “footloose” shall we say?

Immigrants are defined by having moved from home. I mean, that’s how we know that they’re immigrants: they left their home country and moved to the US. And there’s something special about a person that’s interested in doing that. A lot of people want to live close to family. If you’re foot-loose to chase economic opportunity, then it doesn’t necessarily stop when you get to the country. It also means that you’re more likely to move to a city that offers good jobs or a suburb that offers good schools for your kids. Immigrants are more likely to do that than the US-born. The US-born are born into a state and they’re born into a town, and many people stay home.

You and your co-author describe a 1920s natural immigration experiment in Ohio’s two most populous cities [described in the essay above]. I think some anti-immigration types would interpret the Cleveland example as modestly favoring their position. Local wages rose for a bit and then the city attracted native workers from other parts of the country. Canadians and Mexicans, too, but that’s only because they were exempt from immigration quotas. More jobs for US natives are good. And automation on the farm suggests maybe we should do more of that today, especially given advances in AI and robotics.

First of all, we call the evidence as we see it. So, this is what happened after the border closed and we are reporting on it fully. But we read the evidence a little bit differently than you lay out. We see Cleveland (and cities like it) as giving us a window into an economy that had immigrants flowing in and then immigration stopped. In other words, we see Cleveland as a natural experiment that gives us some guidance into what would likely happen in the US as a whole if we shut off immigration.

So what did firms in Cleveland do when the border closed? Did they offer jobs to locals? Maybe in the short run (but here we say just “maybe” because we only have data in 1920 and 1930 on the census years; we have no direct evidence that local workers had higher wages in 1925 or 1926…). But, by 1930, we see no higher income for local workers who lived in Cleveland as of 1920. Instead, we see firms adjusting to the labor shortages in other ways — hiring ‘out of towners’ and unrestricted Mexican and Canadian workers.

By analogy, we then think about the US as a whole as an economy that currently has immigrants flowing in. Would locals (US-born workers) get the jobs that immigrants currently hold? Probably not. The agricultural jobs would probably go overseas and we would re-import the fruits and vegetables, as we already do from some Mexican farms. The landscaping and childcare jobs would probably just disappear. US families might be willing to pay $15 an hour for a nanny to watch their kid, but won’t pay $30 an hour. So probably more moms would stay home and more householders would cut their own grass. The high-skilled jobs would be outsourced as much as possible (do the coding in India rather than have coders move here). Our point here is that firms are flexible and have options. They don’t only turn to the workers next door.

If a country is only willing to admit a limited number of immigrants — the immigrant share of the US population is now around 14 percent — why not try to select the most highly skilled and talented?

First, I do think we should increase the H-1B visa cap, for example. And I’m not saying that we should try to restrict skilled immigration. Our H-1B visa cap has been 120,0000 since the ‘90s. What I like about H-1B is that firms get to pick who they want to work with rather than having the government pick and say, “You have a Ph.D. so you get let in.” Well, not every Ph.D. is the same as every other Ph.D. in terms of what value they have to bring.

On the other hand, though, I do think there is a lot of demand for the kinds of services that low-skilled people can provide [for] kids and the elderly, and agriculture, such as the wide range of vegetables we now have access to compared to when I was a kid and immigration was lower. The concern is: “What if we let in low-skill people and their kids are continuing to be low-skilled and then we have this permanent underclass?” But I think the evidence we bring in the book suggests that we don’t have to be so worried about that. If we have demand for low-skilled work now, we can tap into that demand around the world and then we’ll have another generation of Americans that come from the second-generation kids, and those kids are doing really well.

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples of those interviewees:

Economist Tyler Cowen on innovation, China, talent, and Elon Musk

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on the origins of economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

AI expert Avi Goldfarb on machine learning as a general purpose technology

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy

![Streets of Gold: America's Untold Story of Immigrant Success by [Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan] Streets of Gold: America's Untold Story of Immigrant Success by [Ran Abramitzky, Leah Boustan]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LT7o!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F95a06b09-6618-4660-a797-a20f30f321de_323x500.jpeg)