🌧 Our culture is creating a generation of doomsters and gloomsters

Schools should help counter this pessimism with an evidence-based, pro-progress curriculum ⤴

Are American kids learning what they need to create a better America and world when they are adults? To put it another way, do we have an education system supportive of an optimistic, techno-solutionist Up Wing society of greater prosperity, more opportunity, and deeper resilience?

I don’t think so. It’s not just Swedish teenage environmental activists who have an unduly gloomy opinion of the state of the world and the future of humanity. It’s also too many of the young men and women who live in a certain democratic capitalist country with a reputation for inexorable, can-do optimism. (Spoiler: I’m talking about the US of A!) A few worrisome bits of polling data:

In a 2021 survey of 10,000 people aged 16–25 in ten countries, 68 percent of young Americans agreed that the “future is frightening” because of climate change, with 46 percent also agreeing that “humanity is doomed.”

In a 2020 Monitoring the Future survey from the University of Michigan, nearly 60 percent of American 12th graders agreed or mostly agreed with this statement: “There will probably be more shortages in the future, so Americans will have to learn how to be happy with fewer ‘things.’” (Only 15.5 percent disagreed or mostly disagreed.) Greta Thunberg, who has famously lambasted the West’s “fairytales of eternal economic growth,” would surely agree. She would probably also be all aboard with the 37.5 percent of high school seniors who say they sometimes or often worry about population growth, and the 32.6 percent who sometimes or often worry about energy shortages.

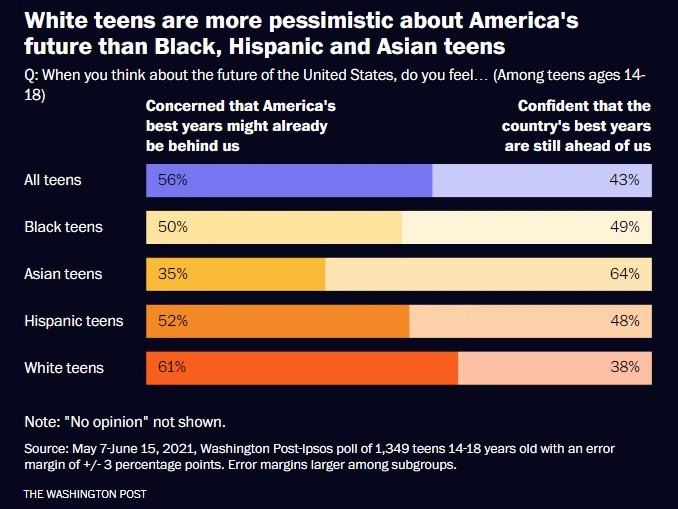

A 2021 poll run by The Washington Post and Ipsos found that a majority of teens — 56 percent — said they believe America’s best years are behind us, a shift from 2005, when roughly the same percentage said the country’s best years were still ahead of us. White teens were more apt to believe that the American glory days are gone.

Teach your children well … about the actual state of the world

I recently wrote about my model for Up Wing thinking: Herman Kahn, the Cold War nuclear theorist turned sunny futurist and advocate for supercharged techno-capitalism. One of his final projects before his death in 1983, the New York Times reported in his obituary, was an education program that would, in Kahn’s words, address “the imbalance of unrelenting negativism” about the future of the world being taught in public schools with “more accurate and therefore more optimistic data” about economics, energy, food supplies, pollution, population, resources, and technology. He obviously hoped such a program would serve as an evidence-based reality check to the era’s raging Down Wing eco-pessimism.

Yes, I wrote “evidence-based.” Take the notion that ravenous, uber-consumptive humanity is fast gobbling up the planet. In Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know, Ronald Bailey and Marian Tupy point to research by Tupy that finds the inflation-adjusted price of 50 key global commodities fell by 36.3 percent between 1980 and 2017. (Of those 50 commodities, 43 declined in price, two remained equally valuable, and five commodities increased in price.) And taking into account that between 1980 and 2017, inflation-adjusted global hourly income per person also grew by 80.1 percent, those commodities became 64.7 percent cheaper. Commodities that took 60 minutes of work to buy in 1980 took only 21 minutes of work to buy in 2017. From the book:

In a competitive economy, humanity’s knowledge about the value and availability of something tends to be reflected in its price. If prices fall, resources can be deemed to have become more abundant relative to demand. If prices increase, they can be deemed to have become less abundant, again relative to demand.

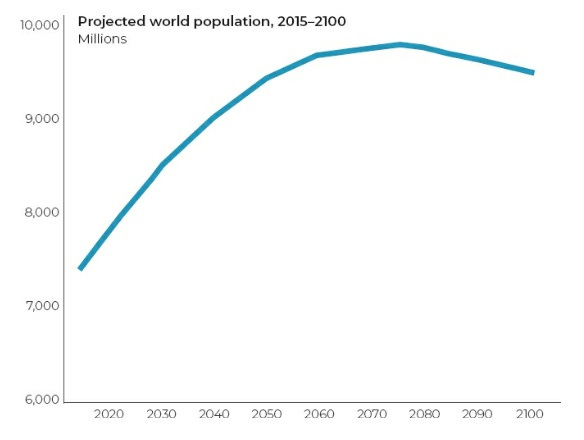

And don’t worry that global population will just keep growing and eventually use up all those commodities. Those late 20th-century forecasts of an Earth with 30 billion of us aren’t happening. Again, from Ten Global Trends Every Smart Person Should Know:

Parents also could use a reality check of their views

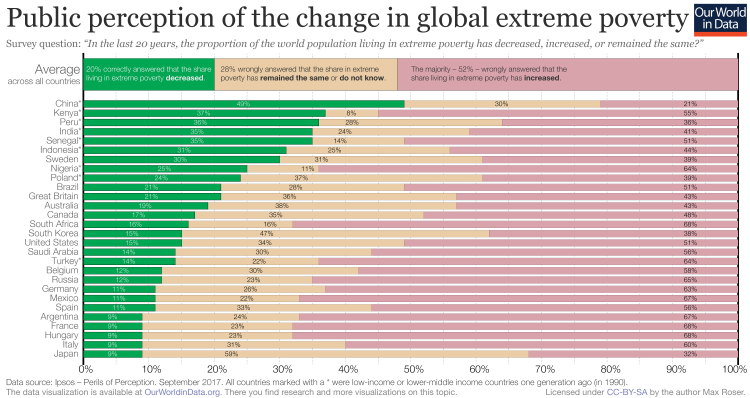

Of course, it isn’t just the kids with a distorted view of the state of the world. For example: The majority of Americans, 51 percent, think the number of those living in global extreme poverty has increased over the past two decades versus 15 percent who correctly say that it has decreased:

Now I certainly don’t have a handy chart or graphic to dispel broad concerns about climate change. Human activity is altering the climate and doing so in ways likely to impose serious costs on humanity. To communicate that message, you probably can’t beat this one from The Economist:

For new readers and subscribers, my baseline climate case: The serious impacts from climate change likely don’t pose an existential threat to human survival, civilization as we know it, or the greater fulfillment of our potential as a species. I take some comfort from the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the UN’s advisory body on climate. IPCC modeling now suggests that more extreme temperature changes are less likely than previously thought.

As climate scientist Zeke Hausfather, director of climate and energy at the Breakthrough Institute, recently told Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip: “If your focus is all about the tails of the distribution, it’s a reason to be a little less worried. But at the same time, if you’re hoping climate may not be that big an issue, it’s a reason to be more worried.”

Yet even if you travel to the dark places found in those tails — places where there’s a “non-negligible” probability of a “collapse of planetary welfare,” according to the late Harvard University economist Martin Weitzman — all is not lost. Even in the most extreme climate scenarios, “there would remain large areas in which humanity and civilization could continue,” writes Toby Ord, a senior research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, in his 2020 book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity.

In short, Earth is highly unlikely to become utterly unlivable, much less Venus. Young Americans should know that. They should know global hunger and poverty have been declining, that we’re not running out of Earth, and that declining population — not exploding population — will be the real economic challenge for many countries.

Creating a pro-progress education system — or even just a single class

I love the idea from Nobel laureate Edmund Phelps to have schools assign more books that will inculcate a desire to discover and explore. “What a modern economy needs more than personnel with expository skills is people eager to exercise their creativity and venturesome spirit in ever-new and challenging environments,” writes Nobel laureate Edmund Phelps in Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change. Jack London, Jules Verne, Willa Cather, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Arthur Conan Doyle, and H. P. Lovecraft are among the authors Phelps ticks off. So teach those classics, as well as newer Up Wing works of adventure and imagination, from the short stories of Asimov, Clarke, and Ray Bradbury to Andy Weir’s The Martian.

But to get back to Kahn’s project, we also need to give kids a true sense of the world they live in. And doing that is so much easier than 40 years ago. I would love to see a class or an entire curriculum infused with the work of Max Roser and the folks at Our World in Data, who supplied a couple of the above charts.

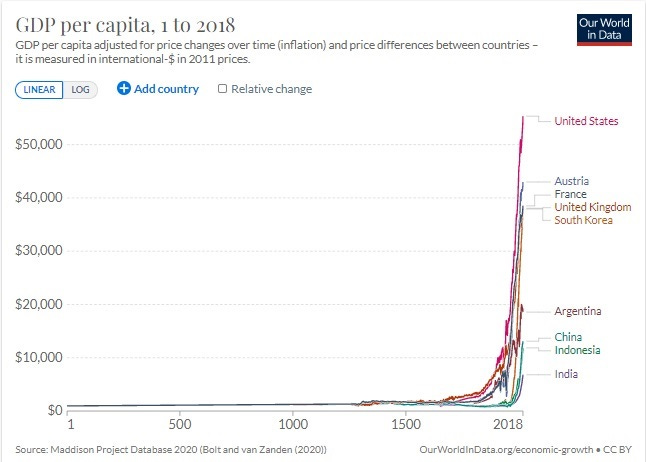

Roser leads the Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development at the University of Oxford and is co-executive director of Global Change Data Lab, the non-profit organization that publishes and maintains the OWID website and its data tools. OWID has published more than 3000 charts covering nearly 300 topics. Among them: hunger and undernourishment, global economic inequality, and human rights. And, of course, you can find what I think is the most important chart of all time:

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples:

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy