😨 What to do about 'climate anxiety,' America's new dystopian disease

Also: 5 Quick Questions for . . . technology journalist and optimist Kevin Kelly

“A world without discomfort is utopia. But it is also stagnant. A world perfectly fair in some dimensions would be horribly unfair in others. A utopia has no problems to solve, but therefore no opportunities either.” - Kevin Kelly, The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

In This Issue

Long Read: Eco-anxiety: America's new dystopian disease

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for . . . technology journalist and optimist Kevin Kelly

Micro Reads: jobs on the rebound; European VC, an impossible material, and more …

Nano Reads

Long Read

🦠 Eco-anxiety: America's new dystopian disease

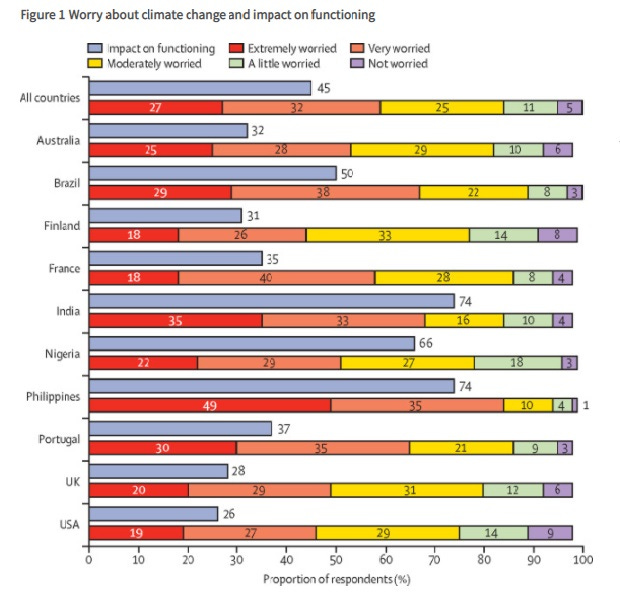

Climate change makes many people gloomy about the future. Just check out a poll published last month in The Lancet. The survey covered 10,000 people across 10 countries. Overall, 45 percent said their feelings about climate change affected their daily lives, 75 percent said the “future was frightening,” and 56 percent said “humanity is doomed.” Among only Americans, those numbers were, respectively, 26 percent, 71 percent, and 48 percent.

Of course, being concerned or pessimistic about something doesn’t mean you need to seek therapy. But according to a big weekend feature in The New York Times, “Climate Change Enters the Therapy Room,” there’s a growing field of climate psychologists who treat eco-anxiety. The possibility of such a malady was first proposed a decade ago by Portland psychologist Dr. Thomas J. Doherty and Susan Clayton, a professor of psychology at the College of Wooster.

Early skepticism about the diagnosis, the NYT explains, is fading: “Though there is little empirical data on effective treatments, the field is expanding swiftly. The Climate Psychology Alliance provides an online directory of climate-aware therapists; the Good Grief Network, a peer support network modeled on 12-step addiction programs, has spawned more than 50 groups; professional certification programs in climate psychology have begun to appear.”

Much of the piece is devoted to telling the stories of eco-anxiety sufferers — perhaps triggered by an overly packaged item in a grocery store — who end up “doomscrolling” worrisome climate news or plunging down a rabbit hole of YouTube research. “Multi-day panic episodes” afflicted one person mentioned in the piece. Another, seeing the plastic toys and disposable diapers in her home, described her condition this way: “I feel like I have developed a phobia to my way of life.”

My baseline climate case: The serious impacts from climate change likely don’t pose an existential threat to human survival, civilization as we know it, or the greater fulfillment of our potential as a species. Burning fossil fuels isn’t going to turn Earth into Venus. Even in the most extreme climate scenarios, “there would remain large areas in which humanity and civilization could continue,” writes Toby Ord, a senior research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, in his 2020 book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. (Here’s my 2020 podcast chat and transcript with Ord.) And while technological progress is what has perturbed our climate, it also provides the tools for mitigating impacts while increasing global prosperity.

Validating the eco-anxious is an important first step

But before attempting to make a tech-solutionist case to an eco-anxiety sufferer, it would be important to validate their feelings. To be clear: I’m using the word “validate” in the therapeutic sense: empathetically communicating that a particular feeling isn’t “silly” or ”crazy,” that there’s a kernel of truth in there — but without necessarily agreeing with the totality of the concern driving the anxiety. Climate change isn’t a hoax. Humans are doing something unique to our atmosphere. The worst consequences identified by those UN climate reports are daunting. As economist Martin Weitzman put it in a 2009 paper: “The probability of a disastrous collapse of planetary welfare from too much CO2 is non-negligible, even if this low probability is not objectively knowable.”

So there is something there. The feeling of anxiety isn’t wrong. That said, validation isn’t a concession that some who see the problem of climate change as I do would make. But validation is an admission ticket here. It allows the conversation to continue. A typical next step in therapeutic behavioral therapy is to urge patients to “check the facts” to see whether the emotional experience fits the reality of the situation.

And I wonder if that isn’t where the therapeutic process described in the NYT piece breaks down. I wonder if the climate therapists know enough to challenge eco-pessimist patients trapped inside an alarmist information bubble — one created by climate activists and some scientists who see overstating risks as key to prompting action. Indeed, many climate therapists might themselves be inside such bubbles.

One problem: If you’re worried about climate change and are also being told that a catastrophic tipping point is only a few years away, checking those “facts” will probably only heighten your anxiety. In this regard, some in the climate change community, as well as Hollywood and much of the mainstream media, are performing a great disservice in their persistent climate dystopianism. The 2021 paper “Parents think—incorrectly—that teaching their children that the world is a bad place is likely best for them” by Jeremy D. W. Clifton and Peter Meindl suggests just how harmful it is to have a negative worldview pushed on you. Instilling such beliefs is “almost never associated with better outcomes. Instead, they predicted less success, less job and life satisfaction, worse health, dramatically less flourishing, more negative emotion, more depression, and increased suicide attempts.”

We need to tell ourselves a different story about the future

But there’s a different story to tell than one of impending doom where without a totally unlikely global cooperation and change in lifestyle ASAP, well, humanity is doomed. For instance, there’s the “solarpunk” genre of science fiction that imagines a green, clean world of rewilded landscapes, windmills, and rooftop gardens. As Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac write in The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis: “It is 2050. In most places in the world, the air is moist and fresh, even in cities. It feels a lot like walking through a forest, and very likely this is exactly what you are doing. The air is cleaner than it has been since before the Industrial Revolution. We have trees to thank for that. They are everywhere.” (This is closer to the vision portrayed in by the Smithsonian Institution’s “Futures” exhibit, which I recently wrote critically about.)

The post-capitalist aspect of solarpunk, as well as its dream of a no-growth, anti-consumerist ecotopia built around self-sustaining local communities of artisans, might be of some comfort to some eco-pessimists. Solarpunk art is also pretty cool.

How about a story of abundance and progress?

But I prefer a different story: Imagine if all of what we know now about climate change was known 100 years ago. And what if the sort of scary impacts from climate change, such as rising sea levels and deadly droughts — the kind of things forecasted to occur over the next century — had actually started to happen a century ago? What could we have done in a world that had only recently discovered the combustion engine or had begun the long process of electrification?

Maybe a relatively wealthy and technologically sophisticated nation might have managed to build a sea wall to protect low-lying coastal areas — but most places in the world could not have managed it. As physicist David Deutsch points out in his 2011 book The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World, “All relevant machines were underpowered, unreliable, expensive, and impossible to produce in large numbers. An enormous effort to construct a Panama canal had just failed with the loss of thousands of lives and vast amounts of money, due to inadequate technology and scientific knowledge.”

Then what? How would we even have gone about predicting the rise in carbon emissions over the rest of the 20th century without computer modeling? And the ability to generate clean nuclear energy was nowhere on the horizon. Deutsch points out that “radioactivity itself had only just been discovered, and would not be harnessed for power until the middle of the century.” But that is not our condition today. Technological progress is giving us options for clean and abundant energy — including advanced nuclear and geothermal — as well as for geoengineering options such as solar radiation management and carbon capture. The future doesn’t need to be frightening.

What’s more, progress in sectors such as biology, computer science, energy, and space suggests it isn’t crazy to think this decade may eventually be worthy of the “New Roaring ‘20s” sobriquet. America may be leading the world in finally realizing the expansive techno-optimistic visions of postwar futurists. Maybe would we see less eco-anxiety in society if societal elites were telling us a different story about our possible environmental future.

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for . . . technology journalist and optimist Kevin Kelly

Kevin Kelly founded Wired in 1993, and served as its executive editor for its first seven years. His latest book is The Inevitable, which is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller. Other books by Kelly include New Rules for the New Economy, Out of Control, and What Technology Wants. I was intrigued by Kelly’s recent essay “The Case for Optimism,” which I briefly wrote about a few weeks ago and wanted to ask him a few questions about it.

1/ How do you define optimism and how would you distinguish it from naive utopianism or pollyannaism?

Utopians and pollyannians believe in a harmonious destination without problems. Real optimism requires problems, and there is no endpoint; it is an eternal process of becoming. It is through the process of endless problems that we gain progress. An optimist aims for a tiny bit of progress, a world that is a tiny bit better this year than last year, even though this new world will have major new problems. So I am optimistic because we can keep creating options for good even as we create new troubles.

In the end, optimism is a type of imagination. You imagine a plausible future you want; then you imagine how you might arrive there, what kind of problems will assist you, and the kind of processes you need to keep going. It never ends in utopia. I call this type of optimism, protopia. “Pro” as in progress, proceeding, and the affirmative pro, as in pro vs con. Protopia is what has gotten us here today in 2022. Since you can’t make any kind of complicated good unless you first imagine it, in the long run, it is imaginative optimists who shape the future.

2/ What are the most powerful incentives to short-termism or impediments to long-term thinking in American society today?

All humans discount the future. We would rather have a million dollars today than in 30 years from now. We’d rather a flimsy bridge today, rather than a sturdy, durable bridge 5 years from now. We’d rather eat all the fish in the waters tonight, than to go a little hungry and leave fish for others in the future. To delay instant gratification requires cultural training. To be convinced of the value of investing into the future requires a kind of wisdom, knowledge, patience and trust that is gained from history, elders, and system thinking. It requires collective action and collaboration on a large and long scale. It requires civilization. Civilization is a system of trust, both in the goodness of humans today, but also in the ingenuity of humans in the future. It’s a way for humans to trust the future. Civilization is a social machine accumulated over many generations and is constantly being tested by new events. American society over emphasizes the individual's self-interest, and over-relies on the marketplace to solve social problems, and so coddles the short term. Modern Americanism tends to ignore the government which can take the long view because it is inefficient.

But the calculus of efficiency is shifted when taking the long view. Storing adequate supplies for a population that are only used in an emergency is inefficient in the short term and this inefficiency is not something companies can afford to do. That short-term inefficiency, however, makes total sense in the long view because it is highly efficient over time. Investing into a communal project that may not pay off until you are long gone is not a natural reflex of modern Americans, whether liberal or conservative. The antidote to this natural focus on the short term is education and a shift in norms. As we continue to civilize ourselves, we can appreciate the gifts of past long-term work, and the need in our fast-moving world today to pay the gifts forward by investing into work that will likely pay off in future generations.

3/ You've written that new tools are accelerating learning, which will accelerate innovation and progress more broadly. But remote learning during the pandemic has experimented with new technologies and led to poor educational outcomes. Does this curb your optimism?

Two shifts in learning are taking place worldwide. The first shift is where learning happens. Increasingly the core learning — the learning that will manifest itself in new ways and new things in the world — is not happening in classrooms. Any measurement of learning in classrooms is bound to be disappointing. Some learning takes place in schools outside the classroom, in sports, in the arts, in events where students take over. Effective learning has shifted online, where infinite libraries and ultimate encyclopedias live, where you can use AI-assistants to find answers. A major source of learning today is YouTube, and its influence is under appreciated. It is not just make-up artists and guys in their garage sharing tips. It’s professional programmers who go to YouTube to figure out how to do a bit of tricking coding. It is scientists attending talks on papers in distant places too far to travel. It’s brain surgeons watching videos of their colleagues performing new procedures in the operating room. The next day they are trying the procedure themselves and coming up with slight improvements, which they then video and post that week.

The result of all this vast activity is the second shift: the acceleration of learning. The speed at which innovations are shared has been increased so much by videos that significant progress can be made in a matter of days, instead of years in the past. Ideas, concepts, techniques, methods, data, and insights that would ordinarily have taken 12 months to be written up, reviewed, printed, and distributed, can fly to all continents in minutes now. This new velocity is due to the ease of “publishing” on a peer platform like YouTube, and also to the greater ease in understanding that moving images provide. For many subjects, a video is easier to comprehend than text. But for ages, the cost and difficulty of producing video kept it away from the everyperson. Now the everyperson can make a video with their phone. So BOOM, we have instant peer-to-peer teaching/learning happening at great scale. I am not aware of any field where YouTube (or Youku in China) has not sped up learning already. As augmented reality (AR) slowly evolves and penetrates working lives, I expect the velocity of learning to exponentially increase again.

4/ You argue that as AI becomes ubiquitous, humans will need to leverage their comparative advantage. What does that look like for lower-skilled or lower-income workers?

Some of what we call low-skilled work (hair salon, dental hygienist, child care, tour guide) will over time become high-paid work because we want humans to do it. Stuff that we want humans to do will cost more. The low-skill work that robots do take over will be jobs no one really wants to do — cashier, fruit picker, forklift driver, ditch digger, package deliverer. Working in a mine or hauling boxes in a warehouse are jobs we will soon be ashamed that humans ever did. Those jobs will go to the robots because we care if they are done efficiently, and robots are all about efficiency. In fact, wherever efficiency or productivity counts, robots will rule.

But an awful lot of what we humans care about is not efficient or productive. We love to chit chat, and explore places new to us, and to invent, read, create, sing, dance, cook, write, watch entertainment — and none of those things are efficient. To earn money, to create value, we need to think different, to make new things, to innovate, to discover and explore — and all these are inefficient. Science is inefficient. Innovation and entrepreneuring are inefficient. As automation owns more of what can be done efficiently, it liberates us humans to focus on those things we do inefficiently — from the creative to the social. Not all these roles will be high paying; not all will be focused on creativity. Some merely require us to be our best as social beings. Often times those who don’t have a lot of ambition, or opportunity, may shine the brightest at being human, which will be in demand.

5/ Might we see an anti-automation backlash much the one we’ve seen with trade?

Backlashes are usually paper tigers that appear more significant than they are. I lived through the hippy backlash against the Establishment in the 1960s–70s and it only moved culture in a most indirect and delayed way. People today chatter about a backlash against hi-tech, but there is really no significant backlash in the real world. Even the critics of technology have not stopped using technology (except a microscopic fraction). Media and social media amplify the decibel of backlashing, even though it is almost silent in the great scale of things. We hear about a backlash against surveillance, but there is no backlash in terms of people’s actual behavior. They behave as if so-called privacy is not important. In fact, striving to become a famous influencer is much closer to how people actually behave. As I say, vanity trumps privacy. So I don’t expect much anti-automation backlash. There will be a few loud luddites, because there needs to be, and lots of people who wish they were more like the Amish, but the liberation from the tedium that automation delivers is too cherished to be abandoned for real.

There will be lots of people who don’t like AIs; they don’t like the alien sensibility that AIs have. They don’t resonate with their alien style of thinking, or their weird alien creativity, nor will they enjoy their odd style of conversation. So we can expect shunning of higher-cognitive AIs by many people that also accept lower-cog robots. At the same time there will be a slice of people who enjoy the alien intelligences of AIs, the same way they enjoy the alien intelligences of animals and pets. They gravitate to these automated thinkers, and a few even become AI whisperers, who are able to empathize with them. But for the most part, the benefits that artificial intelligences bring will exceed the benefits that artificial power brought in the industrial revolution, and just as no one, including the Amish, has totally relinquished automated electricity and heat, very few will give up AI and robots.

Micro Reads

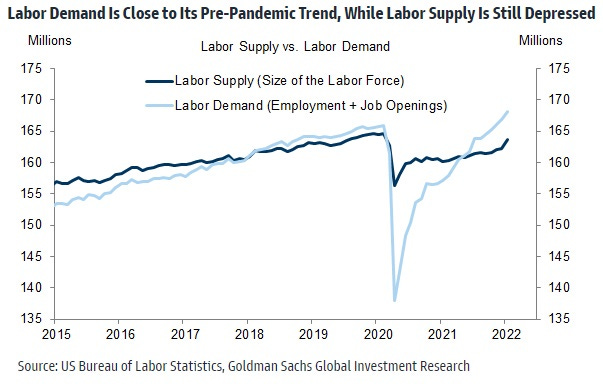

👷♂️ US Economics Analyst: Missing Workers and Rising Wages - Goldman Sachs | The bank’s economists look at depressed labor force participation and calculate there are roughly 2½ million missing workers. Assuming 0.8 million of these have retired early — thanks in part to rising home and equity prices — leaves 1.7 million people who are candidates to return to the labor force. What’s taking them so long? From GS:

Workers give three main reasons: they have Covid-related concerns, they have a financial cushion, or their lifestyle has changed. These explanations suggest that some people are likely to come back if virus spread falls or antiviral pills reduce health risks, and others are likely to come back once they exhaust their savings, especially now that most special pandemic fiscal transfer payments have expired. In support of this expectation, most prime-age workers who left the labor force say they intend to re-enter. . . . We forecast that about 1 million people will return to the labor force this year, raising the participation rate to 62.6% by year-end, and that more will come back in later years. Even so, the depressed participation rate implies that workers will be even harder to find than the unemployment rate suggests.

📈 This Week in the COVID-19 Recovery - Mark Zandi, Moody’s Analytics | Another cheery economic forecast — with one significant caveat:

Nevertheless, if the recent pace of job growth is sustained — and it is difficult to see what could deter it — the economy will fully recover the close to 3 million jobs still missing from the pre-pandemic peak by mid-year and return to full employment by year end. Full employment would be consistent with an unemployment rate that is below 3.5%, down from its current 4%, and a labor force participation rate closer to 63%, up from its current just-over 62%. . . . The severe labor shortages will abate. . . . This sanguine outlook for the coming year, with the economy returning to full employment and inflation moderating, depends on the Federal Reserve successfully calibrating monetary policy.

🔬 House Passes Bill Adding Billions to Research to Compete With China - Catie Edmondson and Ana Swanson, The New York Times | This is kind of mess. "Deep ideological differences remain between the two chambers [of Congress] over how punitive to be against China and how to fund scientific research.” House Democrats have garnered little support from across the aisle with a bill that Republicans have criticized for its climate change and unrelated research provisions. Meanwhile, the Senate version of the bill privileges research in bleeding-edge tech like quantum computing and advanced AI. Some Senate Republicans, in an effort to get tough on China, have embraced an industrial policy of investments and subsidies aimed at competing with China, especially in the semiconductor sector, while other Republicans remain opposed to a policy of "picking winners and losers."

🦄 Venture capital’s new race for Europe - Sebastian Mallaby, Financial Times | Top computer science programs, the increasing number of unicorn tech startups in Europe, and the possibility of hiring remote workers across a wide geography could be signs that the European tech sector is ready to rock. European countries haven't historically nurtured tech startups the way the US does, but now that the VC cash is flowing, Europe's leaders would be wise to take advantage of the opportunity.

⏩ Why the impressive pace of investment growth looks likely to endure - The Economist | Any kind of sustained productivity boom this decade will also need a sustained strengthening in business investment. Why might that happen? Three reasons: First, “companies are likely to keep spending on their supply chains as they seek to strengthen and diversify them.” Second, there’s “growing optimism about the potential of new technologies to boost productivity growth. … Intellectual property now makes up 41% of America’s private non-residential investment, compared with 36% before the pandemic and 29% in 2005. In 2021 the big five technology firms—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta and Microsoft—alone spent $149bn on r&d.” And third, decarbonization goals means “the world will need everything from electric-vehicle charging infrastructure to battery storage and energy-efficient housing.”

💡 MIT Engineers Create the “Impossible” – New Material That Is Stronger Than Steel and As Light as Plastic -SciTechDaily | Chemical engineers at MIT have invented a mass-manufacturable, strong, and light new substance by creating two-dimensional polymer sheets — an achievement once thought impossible. This new plastic material's applications range from durable coatings to building material for bridges and thin membranes impermeable by water and gases."The researchers found that the new material’s elastic modulus — a measure of how much force it takes to deform a material — is between four and six times greater than that of bulletproof glass. They also found that its yield strength, or how much force it takes to break the material, is twice that of steel, even though the material has only about one-sixth the density of steel."

Nano Reads

▶ Metamorphosis: Facebook and big-tech competition - The Economist |

▶ Implanted spinal stimulation device allows patients to stand, walk and swim - Kaitlin Sullivan, NBC News |

▶ What If Our Technology Turns Against Us? - Tyler Cowen, Bloomberg |

▶ Steven Pinker: Why We Should Be Hopeful for the Future - Steven Pinker, Reader’s Digest |

I love Kevin Kelly and his work, but he got one point completely wrong. "American society over emphasizes the individual's self-interest, and over-relies on the marketplace to solve social problems, and so coddles the short term. Modern Americanism tends to ignore the government..."

This is so backward! Americans now turn reflexively to government to solve everything, despite government's inability to do so. There has been a strong trend away from self-reliance and personal responsibility. We rely on the marketplace far TOO LITTLE to solve problems that its distributed intelligence can solve far better than government -- when government gets out of the way and doesn't bury the market in regulations.

Always a great read, James. Thanks much for the effort you put into it.