👶 China's baby bust is a huge opportunity for America

Also: 5 Quick Questions for . . . labor economist and automation expert Carl Benedikt Frey

“For in the end, the greatness of America depends not on its force of arms, or even the opulence of its economy, but upon the power of its message for the world.” - Joel Kotkin and Yoriko Kishimoto, The Third Century: America's Resurgence in the Asian Era

In This Issue

Long Read: How China's baby bust can help birth a second American Century

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for . . . labor economist and automation expert Carl Benedikt Frey

Micro Reads: Beatlemania, supercities, the case for optimism, and more . . .

Long Read

👶 How China's baby bust can help birth a second American Century

Pax Romana and the Golden Horde had pretty long runs, but modern countries generally don’t get more than a hundred years or so as the globe’s dominant power. The British had the 19th century and America the 20th. But the 21st century, many experts confidently predict, will be the Chinese Century due to the Middle Kingdom’s massive population, efficient governance, and rapidly growing technological savvy. Bold Beijing gets big things done, while a decadent and distracted Washington dithers. Rising China, Declining America.

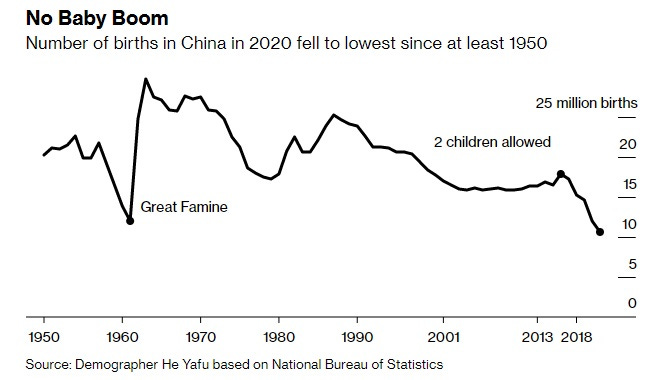

If you’re looking to counter this “Chinese Century” consensus, however, you just got a pretty compelling data point. China’s National Bureau of Statistics said Monday that the number of newborns fell for a fifth straight year, sinking to the lowest number in modern Chinese history. There were, according to the agency, 10.62 million births, down from 12.02 million in 2020 — barely outnumbering the 10.14 million deaths. Those results put China’s year-end population at 1.413 billion, up a tiny 0.034 percent from 1.412 billion at the end of 2020. (The birthrate — the number of births per thousand people — fell 7.52 in 2021 versus 8.52 in 2020.) “China is facing a demographic crisis that is beyond the imagination of the Chinese authorities and the international community,” Yi Fuxian, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told The New York Times.

And China’s demographic crisis is happening despite a persistent push by Beijing to get its people to have more babies. In 2016, Beijing scrapped its four-decade one-child policy and allowed married couples to have two children, leading to a brief upward blip in the birthrate. Officials have also banned private tutoring to constrain soaring education costs and made it illegal to discriminate against young mothers in the workplace (although new laws do not seem to be enough to fight cultural expectations about the role of women in Chinese society). Local governments have also tried various natalist measures, notes The Wall Street Journal, including cash rewards and longer maternity leaves.” All to little effect, apparently. The trend “cannot be reversed,” the NYT quotes one Chinese demographer.

As demographically dour as these numbers are, they may actually be severely understating China’s baby problems. In 2019 the United Nations projected that China would still have around 1.3 billion people by 2065. But there’s considerable skepticism about that forecast from various quarters:

A July 2020 study in Lancet suggests Chinese population will halve by 2100, (while India’s working-age population will surpass China’s in the mid-2020s).

In a study published last October, researchers at the Institute for Population and Development Studies at Xian Jiaotong University in northwest China argued that those UN estimates are way off. For instance; Those 12 million newborns in 2020 were 25 percent lower than the UN's estimate. Overall, the study forecast China's population could decline by half within the next 45 years. The projection was based on a forecasted birth rate of 1.3 children per woman versus the current rate of 1.7. Chinese authorities "need to pay close attention to the potential negative inertia of population growth and make a plan with countermeasures in advance," the study concludes.

A report published last November by Simon Powell, analyst at Jefferies, predicts “China’s population will peak in 2022, which is almost 10 years earlier than the United Nation estimates. . . . If births decline by 20% p.a. from 2020 onwards, deaths will surpass births by about 6 million in 2025. We estimate China’s population will peak in 2022, which is almost 10 years earlier than the United Nation estimates.”

There are numerous economic implications that come with a shrinking population, especially a shrinking working-age population. As Goldman Sachs explained last May:

On economic growth, a shrinking working age population will likely lower overall economic growth via two channels. Firstly, a shrinking working age population reduces the potential GDP level and slows down potential GDP growth, holding labor productivity constant; secondly, population aging increases burdens in supporting the senior population: working-age adults tend to work and save more than the young or those aged 60 and older. An economy with a greater working age population is generally assumed to have higher savings rates which would add to GDP growth by boosting investment rates. The latter channel is much less certain than the first however, as empirical evidence from many economies including China suggests that precautionary savings, especially in economies with still-evolving social welfare systems, can be strong even in old age.

I would add that some research finds the older a country’s population, the lower its overall rate of entrepreneurship. And the fewer people you have, the smaller share of the population that can be devoted to doing scientific and technological research, reducing idea creation. In the 2020 paper “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population,” economist Charles I. Jones warns of an “empty planet” scenario of falling population and stagnant incomes.

Of course, the United States has its own demographic issues. Americans in 2020 had the fewest babies since 1979, while the total fertility rate was the lowest since the government started tracking it in the 1930s. Yet the pandemic-driven health and economic crises probably dissuaded some women from getting pregnant. But birth rates never really recovered after the Global Financial Crisis, costing the US some nearly 8 million additional people since the GFC.

Of course, the US has a big advantage over China if it chooses to fully use it: immigration. As it is, the Census Bureau forecasts the US population to expand to just over 400 million by 2060. So we would could be looking at a scenario where China’s population edge over the US would be reduced from 1.4 billion vs. 330 million to 750 million vs. 400 million. Implementing a more expansive US immigration policy could narrow that gap even further. Indeed, why not try to close it completely? Back in May 2020, I did a podcast chat with Matthew Yglesias about his book One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger:

Pethokoukis: One billion by when? And should readers interpret this book as you saying you want a billion Americans by any date? Or is this just more of an interesting thought experiment to argue for more Americans? number, and it makes for a fantastic book title? (I find it very compelling.)

Yglesias: Look, if we settled on 850 million Americans, it would be okay. What’s one billion? It’s a round number. It makes a nice title. One billion by 2100 is two nice round numbers together. By coincidence, we would need Canada’s population growth rate sustained for 80 years to get there. That sounds totally reasonable to me. I’ve been to Canada. You may know Canadians. Listeners may be familiar with it. It’s a fine country. They are doing well for themselves.

Also, one billion Americans would get us the population density of France. It would get us one half the population density of Germany. Those are also countries that people are aware of. They know they have a high standard of living in France and Germany. Say what you will about France, it’s not a dystopian hell of overcrowding, whatever problems people may have with it. They’ve got nice vineyards. There are some woods, a beautiful coastline. Everybody likes Paris.

That’s why I say one billion. Yes, it’s a little bit of a vague aspiration, but it’s an idea that I think we can anchor ourselves on. You need to pick goals in life, and I think this is a good one.

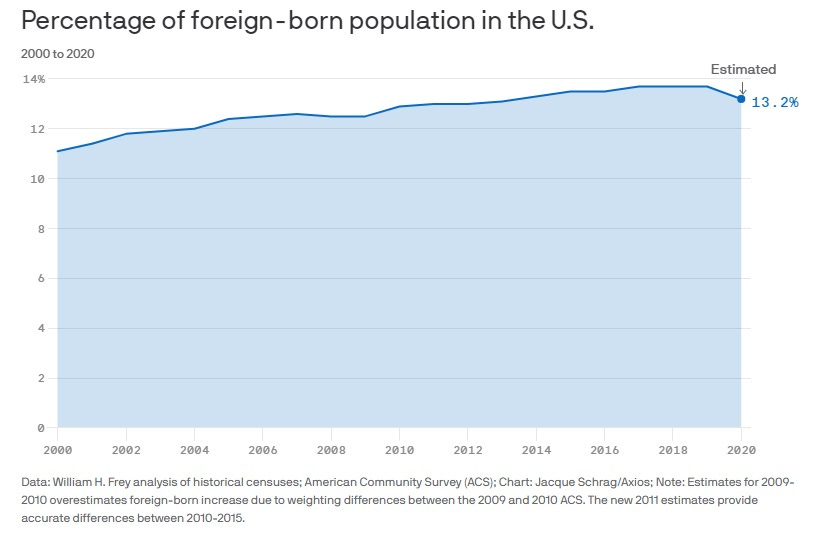

But US immigration seems to be going in the opposite direction right now. Whether you want more Americans for geopolitical, economic, or human rights reasons, this is a bad chart. From Axios last month, it uses experimental Census Bureau data to show that the population of foreign-born citizens and residents plummeted for the first time since the GFC.

How do Americans currently feel about immigration? Despite the rise of anti-immigrant populism, the share of Americans wanting more immigration has boomed over the past decade.

I want the 21st Century to be named after a liberal democracy not a totalitarian surveillance state. US population growth? Faster, please!

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for . . . labor economist and automation expert Carl Benedikt Frey

Dr. Frey is the Oxford Martin Citi Fellow at Oxford University, where he teaches economics and economic history. In 2013, he co-authored a widely-shared paper with Michael Osborne titled “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” in which he estimated that 47 percent of jobs were susceptible to automation. In 2019, he returned to the subject with his new book, The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation. (I also urge you to check out his 2021 essay “How Culture Gives the US an Innovation Edge Over China.”)

1/ How much do you worry about a new anti-tech, anti-automation backlash, one similar to what has happened recently with trade — and, of course, like the ones against automation in the past?

Given current labour shortages, this concern does not seem imminent. But things could change quickly if we enter into a recession. Historically, resistance to automation has been the norm when workers have few alternative job options. For example, there was an upsurge in machinery riots during the years of the continental blockade, designed by Napoleon to disrupt British commerce.

2/ What is your favorite anti-automation example from The Technology Trap?

Probably lamplighters resisting the introduction of electric street light because it shows how job simplification is often just a step towards automation, and that even simplification may not be in workers’ interest. Before electric street light was controlled from substations, each lamppost had a switch which needed to be turned on and off manually. This meant that lamplighters no longer had to carry heavy torches and ladders (previously used to ignite gas lamps). But it also made the task so simple that children could just turn the lamps on and off on the way home from school. Job simplification meant that lamplighters were sometimes replaced by school children.

3/ Do you think the pandemic is leading to increased automation given the shortage of workers and a drive toward efficiency in business?

There are clearly many examples to suggest this is the case. Italian winemakers, for example, who have struggled to find immigrants to work their fields, are reportedly increasingly buying automated grape pickers. However, we don’t have much data on how pervasive the uptake of automation technology has been across different sectors of the economy.

4/ What is a pro-growth economic policy that deserves more attention? Or is helping workers deal with disruption a more important public policy goal right now?

If you care about let’s say venture capital and intellectual property rights, you have probably already decided to become an inventor or entrepreneur. But in order to make that decision, you must have become exposed to inventive activity at some point in the first place. By exposing more people to innovation early in life (e.g. in school), I think we can unlock the potential of many “lost Einstein’s.” How this is best done deserves more attention.

5/ Is it possible to steer innovation so that it is more labor augmenting or labor creating rather than labor replacing?

In theory yes, in practice I’m less sure. There is some evidence that the current tax code favours automation technologies at the expense of job creating ones, so that might be a place to start. But overall I think we need to be humble about our ability to steer technological progress. Especially given the state of our politics.

(If you’re interested in more of Frey’s views, please check out my 2019 podcast chat (audio and transcript) with him.)

Micro Reads

🎶 How Beatlemania holds us back - Janan Ganesh, FT | Hollywood's obsession with reboots, prequels, sequels, and superheroes has become a punchline to commentary on today's cultural and artistic stasis. Perhaps the resurgence of Beatlemania — as exemplified by the new Peter Jackson documentary — is a symptom of the same malady. Ganesh: "It is likelier that people obsess over the Beatles because there is nothing new around, than that there is nothing new around because people obsess over the Beatles. . . . [I]t is possible that the raw weight of their legacy is now more of a drag than a stimulus to the creation of the new. There isn’t a less fitting tribute to innovators than a backward gaze at them." Don’t get back, go forward!

📈 On Supercities, Economic Growth, and Income Inequality in a Post-COVID World - Scott Kupor, Future from a16z | Remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic has begun to decouple geography and opportunity. By replicating Silicon Valley's recipe for success in other locales, the post-COVID moment offers the opportunity to spread economic opportunity to left-behind areas. Some policy suggestions from Kupor to jump-start network effects in those areas: Tax incentives and low-regulation "innovation zones"; highly specialized state universities; local tax and education ecosystems that encourage high-risk seed capital; a federal research endowment, "funded in part by royalty returns on technologies generated by its funding"; increased immigration; and tax preferences or student loan forgiveness programs tied to sectors and geographies pushing technology forward. While markets, not government, should be picking winners and losers, "government is filling a role otherwise abandoned by the free market" when it incents basic (as opposed to applied) research with these policies.

🌌 What makes an "optimistic" vision of the future? - Noah Smith, Noahpinion | I love this piece — and not just because I get a shout-out in the second paragraph. Adding to the Wang Standard I wrote about in a previous issue of Faster, Please!, Smith tries to nail down what makes science fiction feel optimistic by describing the elements of a "radically better" future: (a) “material abundance”; (b) “egalitarianism — broadly shared prosperity, relatively moderate status differences, and broad political participation”; (c) “human agency — the ability of human effort to alter the conditions of the world.”

😃 The Case for Optimism - Kevin Kelly, Warp News | Kelly identifies several reasons for optimism in the current moment:

The continued urbanization and globalization of the world, which will enlarge markets, enable greater collaboration, and boost innovation.

AI will revolutionize the economy with new products and services and new jobs. Combined, the connectivity of the world and advancement of AI will accelerate innovation further.

As sustainable energy sources become cheaper, decarbonization will follow, along with new, electrified infrastructure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on mRNA vaccines, but they are just the tip of the bioengineering iceberg.

A new generation with fresh ideas and ambition, aided by the technologies and universal connectivity of the 21st century, is stepping up to the plate as Baby Boomers retire.

⚛ NIMBYism Is Good If the N Stands for Nuclear - Matthew Yglesias, Bloomberg |

The liberal college town of Amherst, Massachusetts, is considering a ban on new large-scale solar projects that’s supported by, among other groups, the local chapter of the supposedly radical youth climate movement Sunrise. It’s the latest in a long list of unfortunate instances in which renewable-energy projects have faced opposition not from coal barons or reactionaries, but from progressive types concerned about the land-use impacts of big new energy projects. The National Audubon Society is trying to stop a wind project near Oakland, California, for example, and local Audubon chapters are frequently in opposition to this or that clean-energy project.

📈 Productivity Gains Will Outlast the Pandemic - Goldman Sachs | The Wall Street bank expects “persistent pandemic-driven efficiency gains” three reasons:

Strong cumulative productivity gains in 2020-21 in both official and alternative metrics;

The incidence of these gains within digitizing industries, particularly those where Work-from-Home is effective’

The sheer scale of the changes to the workforce and to company business models since 2019.

A bit more on that final point:

The sheer scale of pandemic-driven changes to the workforce and to company business models also argues for a large and long-lasting productivity inflection. These changes include 600 million fewer hours spent commuting every month, as well as possibly 1.4 million fewer cashiers, in-person salespeople, and office maintenance staff. Many of these workers and hours will be reallocated to more productive uses—especially at a time of labor shortages and near-record job vacancies. We also estimate around $900bn worth of home offices and $300bn of consumer IT equipment [laptops, desktops, smart phones, and tablets] is now available for business-sector use. This echoes the output and productivity boom in the ride-sharing industry during the 2010s, when Uber and Lyft successfully monetized the household capital stock of cars.

🚢 America’s Most Automated Port Had Its ‘Most Productive Year’ in 2021 - Dominic Pino, NRO | While there was a record backup off the shore of southern California in 2021, the Port of Virginia had its “most productive year” ever last year, successfully handling a 25 percent increase in cargo volume. The port authority CEO credits automation: “The terminal’s automated stacking cranes means the port spends less time running extra shifts and burning out employees when ships are late.” Looking forward it will increase the port’s total on-dock rail capacity by 260,000 containers per year, to a total of 1.1 million and is deepening its commercial ship channel to allow “two-way traffic of the largest container vessels.”

🏙 1,760 Acres. That’s How Much More of Manhattan We Need. - Jason M. Barr, NYT | Concerns about housing affordability and the impacts of climate change could be solved by expanding Manhattan Island into the harbor. A new proposal looks to extend Manhattan into New York Harbor by 1,760 acres (compared to the Upper West Side’s 1,220 acres), creating New Mannahatta. If built with a density similar to the Upper West Side’s, there could be nearly 180,000 new housing units with a significant number made affordable for low-income households. More land in the harbor would also help NYC fortify against climate change as vulnerable places like Wall and Broad streets are pushed further inland, and protections around its coastline could buffer itself and the rest of the city from flooding. It’s also projected it could pay for itself through sales or long-term land leases.

Man, this blog is great but these commenters leave something to be desired. Keep up the good work, James!

This substack writer obviously knows nothing about the environment. You can't keep increasing the population and expect the environment to function properly. We depend on something called "ecosystem services" which I learned about in 1975, along with global warming, from the professor who would become President Obama's SCience Advisor. Ecosystem services provide clean water, clean air, fertile soil, disease prevention, building materials (lumber), pollination, and so much more. But they depend on healthy, intact ecosystems. A suburb with lawns does not qualify, nor does agricultural land, or land that has been logged. The rise of tick-borne diseases is due to encroachment of human activity into heretofore intact ecosystems.

The reduction of the Chinese birthrate is terrific news for that country and for the world. And the US needs to greatly reduce immigration. ***Too much*** immigration is the thing that has done the most to keep Blacks, and more recently poor whites and recent immigrants down in the US. A new book makes a powerful case for that: Back of the Hiring Line: A 200-year History of Immigration Surges, Employer Bias, and Depression of Black Wealth. ($9 on Amazon).

During times of low immigration, Blacks have always begun to prosper. High immigration—always abetted by the cheap labor lobbies--has always pushed them back down again.

The current surge became particularly damaging in the early ‘90s, when the annual numbers passed 1 million.

Beck is thorough. The book draws heavily on academic research into economic history, publications run by Black people, statements of black leaders beginning with Frederick Douglass, and the determinations of multiple gov't commissions on immigration, all of which warned that mass immigration would take jobs from low/no-skilled Americans.

Had the US followed the recomendatations of these commissions, I suspect that the US never would have attained among the highest levels of inequality among the western industrialized nations.