🌌 Why 'The Expanse' qualifies as optimistic science-fiction

Also: We just saw the worst US productivity growth since 1960. But don’t freak out!

“I cannot help but think we shall know shortly whether civilization in any form and substance comparable to what we have known during most of the preceding twenty-five hundred years in the West is possible without the supporting faith in progress that has existed along with this civilization.” - Robert Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress

In This Issue

Micro Reads: 2022 outlook; hacking climate change; a dose of techno-optimism, and more . . .

Short Read: We just saw the worst US productivity growth since 1960. But don’t freak out!

Long Read: Why The Expanse qualifies as optimistic science-fiction

Micro Reads

📈 2022 Equity Derivatives Outlook - JPMorgan | You may not be an active investor, much less dabble in equity derivatives, but this bullish piece by Marko Kolanovic, chief global markets strategist and co-head of global research at America’s biggest bank, can be seen as an intriguing indicator of Wall Street sentiment (bold by me):

Our view is that 2022 will be the year of a full global recovery, an end of the pandemic, and a return to normal economic and market conditions we had prior to the COVID outbreak. In our view, this is warranted by achieving broad population immunity and with the help of human ingenuity, such as new therapeutics expected to be broadly available in 2022. This would result in a strong cyclical recovery, a return of global mobility, and a release of pent up demand from consumers (e.g. travel, services) and corporates (in particular inventory, capex, and buyback recovery). . . . What are the risks to our view? As the recovery runs its course, markets will begin adjusting to tighter monetary conditions, a process that will likely inject volatility. There are other risks that investors will need to monitor and manage in 2022. They include increased geopolitical tensions in Europe and Asia (in particular related to Ukraine and Iran), a looming energy crisis, uncertainties around high inflation, and the path of monetary policy normalization. Political events will also merit investors’ focus, with important US elections in November and several elections in Europe. The market reaction to risks will likely amplify towards the end of the year as the economic recovery and positioning of discretionary and systematic investors peaks, and the Fed starts increasing rates.

⚙ Lessons learned from half a century of US industrial policy - Gary Clyde Hufbauer (PIIE) and Euijin Jung | Evaluating the success of 18 industrial policy episodes in the US over the past 50 years, the researchers find “the track record of such efforts has achieved mixed success at best.” Though industrial policy can succeed in creating jobs, the associated costs are high, and new jobs often come at the expense of comparable jobs that may have been created elsewhere. Likewise, import protections and government support for a single firm rarely work. And while subsidies and trade measures during the 50-year period were littered with failures overall, research and development efforts like DARPA generally performed well.

💻 Europe needs to wake up to the costs of hosting massive data centres - Marietje Schaake, Financial Times | “Already, data storage and transmission, as well as crypto mining, are slurping up about 2.5 per cent of global electricity usage.” Sounds like we need more energy.

🚁 I’m Not a Pilot, but I Just Flew a Helicopter Over California - New York Times |

The helicopter was equipped with new technology meant to simplify and automate the operation of passenger aircraft. I flew using two Apple iPads and a joystick mounted inside the cockpit. I could take off, turn, swivel, accelerate, climb, dive, hover and land with a tap of the screen or a twist of the stick, much as I would when flying through the digital space of a video game. The system, called FlightOS, provides a glimpse into the future of flight.

🌊 Is ‘hacking’ the ocean a climate change solution? U.S. experts endorse research on carbon-removal strategies. - Washington Post | More recognition that efforts to eliminate fossil fuel use and curb greenhouse gas pollution may not be enough. A new study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommends researching how to tinker with the oceans to get them to suck more carbon dioxide out of the air to fight climate change. “A Research Strategy for Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration” outlines a 10-year, $1.1 billion research program.

😃 Techno-optimism for 2022 - Noah Smith | Will the promised New Roaring Twenties ever arrive? Despite some disappointments, Smith remains “massively optimistic for the decade ahead.” The growth of solar and wind power and the advance of battery technology, along with the promise of fusion and next-generation geothermal, are poised to deliver cheap, abundant energy. And that means more innovation in the energy-intensive world of atoms, not just bits. With biotechnologies like synthetic biology and brain-computer interfaces, “we are finally starting to access the source code of humanity — to gain the ability to hack and rewrite ourselves.” And artificial intelligence and nanotech, Smith predicts, will deliver in a big way during the 2020s. All of this on top of a new era in space led by SpaceX.

💪 Amazon Emerges as the Wage-and-Benefits Setter for Low-Skilled Workers Across Industries - Wall Street Journal | Amazon’s critics may always be with us, but their “Amazon is bad for workers” criticism may need to change a bit. What happens with the retailer and its 1.4 million employees is having a massive ripple effect across the US labor market. And that effect seems to be for the better:

Amazon’s wage increases pass through to workers outside the company, researchers have found, as many employers raise their own pay to combat churn. In September, Amazon announced that its starting wage now averages $18.32 an hour, an amount that’s nearly triple the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. To fight off Amazon, competitors have tried to offer lighter workloads, more flexible schedules, bonus pay and other perks. But Amazon is rolling out new plans to compete in those areas as well.

Short Read

📉 We just saw the worst US productivity growth since 1960. But don’t freak out!

We are either finishing the first or second year of the 2020s, depending on how you determine a decade. And it remains to be seen whether the Twenties will be a New Roaring Twenties of rapid productivity and economic growth. Last year, not so much. But his year, more so thanks to a vaccine-driven dethawing of the American and global economy — not to mention a tsunami of fiscal stimulus. Big banks like JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs are looking for real US GDP growth this year of between 5 and 6 percent. If it happens, that would mark the best annual performance since 7.2 percent in 1984 as the economy rebounded from the deep 1981–82 recession.

Now, we just got a crazy bad number on productivity growth from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nonfarm business sector labor productivity decreased 5.2 percent in the third quarter of 2021 — the largest decline in quarterly productivity since the second quarter of 1960. JPM:

The 3Q decline in productivity disappointed our forecast and was even more of a downside surprise relative to the consensus. The productivity data can be noisy, but with signs that firms are having a hard time finding new employees, it is possible that firms are being forced to settle for less productive workers. Productivity growth generally had been firming earlier in the recovery, but productivity was down 0.5% oya after the drop between the second and third quarters.

Again, quarterly productivity numbers are volatile, especially when a pandemic is causing huge flows of low-wage workers to move out of and then back into the economy. But as pointed out in a recent issue, there are reasons for hope on the productivity front. A recent GS report, which I deep dive, cites three reasons for optimism: mean reversion (total factor productivity has been cyclical and may now be in an upswing), tech acceleration (more intellectual property investment suggests business is more actively incorporating recent advances, such as AI), and a pandemic-sparked increase in dynamism, as measured by business starts and patents.

Long Read

🌌 Why The Expanse qualifies as optimistic science-fiction

The sixth and apparently final season of The Expanse arrives today on Amazon Prime. (Warning, this piece will contain some spoilers.) Based on the book series by James S. A. Corey, the joint pen name of Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck, The Expanse is set in the 2350s when humanity has colonized the solar system. Much of the drama revolves around the tense geopolitical relations among the United Nations of Earth and the Moon (or Luna), the Red Planet’s Martian Congressional Republic, and the Outer Planets Alliance, a burgeoning separatist movement in the asteroid belt and on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. It’s a volatile status quo that gets jumbled when a powerful alien substance, the “protomolecule,” is discovered on Phoebe, a moon of Saturn.

I previously wrote about The Expanse back in early November, “Dune, The Expanse, Foundation: Is the Golden Age of TV producing the optimistic sci-fi we need?” My thesis, then and now, is that science fiction can play a critical role in pushing our culture in a more pro-progress direction. We need a society willing to take risks to achieve aspirational goals and accept the disruptive downsides that come with progress. And science fiction helps provide an image of a future worth striving for.

In the piece, I cooked up the Wang Standard, based on this quote by technology analyst Dan Wang: “Science fiction has the capacity to inspire by setting the vision of a radically better future, and by making it clear that the future won’t happen unless we put in the work.” Then I asked this question:

Do these three pieces of art — setting aside their literature source material — meet the Wang Standard of inspiring a radically better future? Superficially, yes. By showing humanity in the future, all three make it clear humanity has a future! So right there a sharp departure from so much of modern apocalyptic techno-pessimist science fiction obsessed with human extinction due to zombies, plague, and climate change. All three depict a humanity that has not only survived but flourished enough to spread deep into the Solar System and beyond.

That said, none of the three match perhaps the highest incarnation of the Wang Standard, Star Trek. Focusing on The Expanse, I received plenty of responses arguing the show was downright dystopian. The pessimist case is nicely summed up by Gizmodo’s Maddie Stone:

In a poignant shot from the show’s intro, we see that New York City — the seat of this supranational government — is surrounded by a giant seawall, suggesting that catastrophic climate change was one of the history-altering events. And while it’s possible the UN government has the climate situation under control by the events of the show, the planet is still buckling under the burden of its outsized population. Chronic resource scarcity manifests itself both in Earth’s economic structure (a huge percentage of people are jobless, living in overcrowded housing on Basic Assistance from the government) and in the fact that Earthers are deeply reliant on resources extracted from the Belt, fueling a colonialist power dynamic that undergirds much of the show’s drama.

So, no, not the clean and shiny world of Star Trek. Or, at least, not yet. Remember, the harmonious, prosperous, and sustainable Earth of Star Trek comes after World War III. Perhaps the Earth of The Expanse will eventually make to such heights as well.

That said, the progress already made in The Expanse-verse disqualifies it as dystopian and even makes a case for a soft meeting of the Wang Standard. The average lifespan on Earth is 123 years, Mars has three billion inhabitants, and humanity mines deep space asteroids, which it can quickly access due to superspeed fusion spacedrives. Also, the global government of Earth is a democracy. We even see a depiction of an election for a new UN secretary general with televised debates and everything. And while the AI is very smart, it’s not sentient. So no Terminator scenarios. Nor do the robots take all the jobs. As one of the authors put it, “What we have is uncommented automation. It's all around the characters all the time but it's uncommented because it's unremarkable to them.”

And if we stopped right there, The Expanse would have a strong case for meeting the strong-version of the Wang Standard. But then there’s all that stuff about climate change, inequality, and overpopulation. Let’s take each of them in turn:

Climate change. Yes, the climate changed. Ice caps melted. Ocean levels rose. Cities were swamped. And probably lots of other bad stuff happened, resulting in the creation of global government. But humanity survived, so much so that it was able to put three billion humans on Mars. And Earth’s population in the 24th century is four times what it is at the start of the 21st century. Moreover, given advances in energy technology, humanity should be fully capable of pulling carbon out of the atmosphere if it wants to.

Inequality. The political economy here is kind of screwy. Given its advanced technology — AI, robots, fusion, genetics — humanity should be quite productive and quite rich. Even if the super-elite are super-wealthy, the living standards for all of humanity should have risen substantially. And while there’s supposedly a lot of unemployment, there oddly still seems to be plenty for us to do — as economics would suggest. (In that previous essay, I suggest we may be seeing the “lump labor fallacy” in actio .) Asteroid mining, for instance, seems pretty labor intensive. I would also note that Martian space battleships each have a crew of 3,000 sailors. That’s about the same as ocean-going battleships during World War II. Again, lots of automation but also lots of work left for humans.

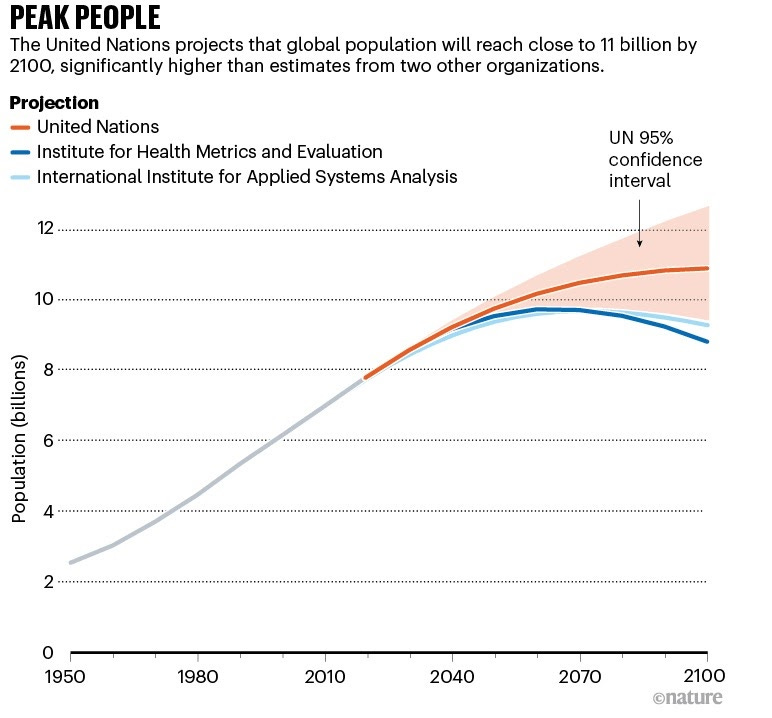

Overpopulation. This seems unlikely. Not sure what would have happened to have changed this real-world demographic trend. The Earth of The Expanse should be well into global population decline.

The problem here is that while The Expanse makes an effort to get the science correct — no warp drives or time travel like Star Trek — it’s far less concerned about getting the political economy correct. It too easily slips into 1970s sci-fi dystopianism — perhaps to help create dramatic tension — and ends arguing against itself. Anyway, I’m sticking to my conclusion from that earlier piece: “Optimistic sci-fi doesn’t need to present a problem-free future. For me, what matters is progress and problem solving. As economist Joel Mokyr has written: ‘Whenever a technological solution is found for some human need, it creates a new problem. . . . The new technique then needs a further ‘technological fix’, but that one in turn creates another problem, and so on. The notion that invention definitely ‘solves’ a human need, allowing us to move to pick the next piece of fruit on the tree is simply misleading.’” Yet all the while, humanity moves forward. And I think that’s happening in The Expanse.

Maybe there should be a Mokyr Corollary to the Wang Standard. Or maybe I need to create a new standard based on the above criteria. The Pethokoukis Standard it is! Or not. Let me end with a quote from The Expanse co-creator Daniel Abraham:

There’s a quote from Camus that is something very much along the lines of, “there’s more to admire in humanity than to despise.” And that’s what we’ve tried to do with The Expanse, both versions of it — the books and the show — look at humanity and find it worth loving, warts and all. With all of the violence and the prejudice and the tribalism, to see that we’re still a pretty amazing species. We’ve done some amazing stuff. And for all of the horror, kindness is still more common. For all the tribalism, the tribes keep getting bigger. If there’s a message that comes through, from that’s what I hope.