🚀 How the Fed can help America colonize Mars

Also: Did Goldman Sachs just make the case for a New Roaring Twenties?

“America stands at a unique juncture in its history. We are more prosperous, more technologically sophisticated, and more integrated into the global economy than ever before. . . . The 20th century ended on a note of great achievement for America, but the century just beginning promises to be brighter still, provided we undertake prudent policies and make strategic investments for the future.” - Economic Report of the President (2000)

In This Issue

Micro Reads: Nuclear fusion, more nuclear fusion, superstar love, and more . . .

Short Read: How the Fed can help America colonize Mars

Long Read: Did Goldman Sachs just make the case for a New Roaring Twenties?

Micro Reads

⚛ Nuclear-Fusion Startup Lands $1.8 Billion as Investors Chase Star Power - WSJ | Yes, I know the joke: Fusion is the future of energy and always will be. But real advances have been made (see next item), and real money is being invested — in this case by Bill Gates and George Soros, among others. As the piece notes: “The recent infusion of cash into fusion startups eclipses the roughly $1.9 billion in total that was previously announced, according to data tracked by the Fusion Industry Association and the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority.”

⚛ Finally, a Fusion Reaction Has Generated More Energy Than Absorbed by The Fuel - ScienceAlert | From the report:

For the first time, a fusion reaction has achieved a record 1.3 megajoule energy output — and for the first time, exceeding energy absorbed by the fuel used to trigger it. Physicists at the National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory will be submitting a paper for peer review. "This result is a historic step forward for inertial confinement fusion research, opening a fundamentally new regime for exploration and the advancement of our critical national security missions," said Kim Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Let me add this: A key fusion milestone is creating a reaction where you put in a certain amount of energy and you get at least as much energy back out. But there are milestones beyond that. And as Arthur Turrell, author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet recently told me in a podcast Q&A:

The next [milestone] that is something that you called wall-plug energy gain, and sometimes I call it the energy it takes to keep the lights on in the facility. So if you’ve got this experimental reactor, it’s the energy to charge up the capacitor banks, a type of battery. It’s the energy to keep the diagnostics running. It’s the energy to keep the lights on. It’s all of that peripheral machinery that you need to do a fusion experiment that isn’t just about the reactor, the experiment, the scientific bit itself, and that requires a gain, not of 100 percent — so one unit of energy out for energy in — but a gain that’s appreciably more than that. It depends on the reactor, but I think what people would really like to achieve is at least 30 times energy out for energy in.

🌠 The streaking star effect: Why people want superior performance by individuals to continue more than identical performance by groups - Jesse Walker (Ohio State University) and Thomas Gilovich (Cornell University) | Maybe Bernie Sanders is undermining his own efforts when he points to the wealth of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk in tweets like this one:

From the study: “We present evidence in 9 studies (n = 2,625) for the Streaking Star Effect — people’s greater desire to see runs of successful performance by individuals continue more than identical runs of success by groups. We find this bias in an obscure Italian sport, a British trivia competition, and a tennis competition in which the number of individual versus team competitors is held constant.”

But it’s not just sports where the Shooting Star Effect has relevance. In one study, participants who thought a company’s success was because of a shrewd CEO rather than shrewd management teams thought the first company should command a greater market than the one benefiting from the collective effort. People enjoy being “awe-inspired” by individual achievement. (Thanks to Ethan Mollick for the pointer.)

☀ This Crazy Museum Exhibit Has Flying Taxis, Floating Cities, And More - Screen Rant | I am going to this: “Want a glimpse of the future? Travel to Washington DC and hit the Smithsonian. Imagining the future and new technology is what every generation does. While some dream of flying on extravagant jet packs, others take their dreams further and work to bring to life their visions.”

Short Read

🌌 How the Fed can help America colonize Mars

Red Planet? Or Fed Planet? Earth’s rust-colored planetary neighbor just got a rare — indeed, it may have been the first time — shout-out from a Federal Reserve official. In remarks yesterday at the American Enterprise Institute (where I work), Randy Quarles, who is stepping down as a Fed governor later this month, warned about mission creep stemming from the lending facilities created by the central bank at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. As the Financial Times reports (bold by me):

Quarles said that the facilities put in place for the pandemic had “established the precedent that the Fed can lend to businesses and municipalities”, which would encourage those with grand plans and little patience for democracy to demand more action in the future. “There will inevitably be those . . . who will begin to ask why the Fed can’t fund repairs of the country’s ageing infrastructure, or finance the building of a border wall, or purchase trillions of dollars of green energy bonds, or underwrite the colonisation of Mars.”

The Fed rarely dabbles in subject areas more commonly found in science fiction (the above image of a colonized Mars is from Canadian artist Mauricio Pampin. More of his fantastic art here), even in jest. For example: When former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke mentioned “robotics” in a 2014 commencement address, he was the first US central-bank boss to use the word in a speech since Alan Greenspan in 2000. (Another sign, perhaps, of America’s 21st-century productivity slowdown. More below in my Long Read.)

But sometimes even bankers loosen up a bit. One of my all-time favorite papers from a Feddie, also from 2014, is “The Future of U.S. Economic Growth,” by San Francisco Fed economists John Fernald and Stanford’s Charles Jones. (The paper was released by the SF Fed, though technically it just reflects the views of the authors.) Fernald and Jones offer a fascinating bit of speculation about the future of technological progress:

. . . artificial intelligence and machine learning could allow computers and robots to increasingly replace labor in the production function for goods. . . . In standard growth models, it is quite easy to show that this can lead to a rising capital share — which we intriguingly already see in many countries since around 1980 — and to rising growth rates. . . . [If] capital can replace labor entirely, growth rates could explode, with incomes becoming infinite in time. . . . [T]he shape of the idea production function introduces a fundamental uncertainty into the future of growth.

Look, if a Fed economist can hint at the Singularity, certainly a Fed governor can make a joke about colonizing Mars. Yet, for a moment or two, let’s take Quarles’ remark seriously. Could the Fed help America turn Mars into the 52nd state (in this scenario, the Moon would be 51, something New Gingrich once suggested)? I think so, but not by having the Fed purchase special Mars Bonds or open credit lines to SpaceX and Blue Origin.

Here’s how: The level of tech progress and economic growth required for America to become a spacefaring nation (and solve lots of problems here on Earth, from climate change to longevity) requires a citizenry supportive of an open economy — including unfettered trade and substantial immigration — and the “creative destruction” that goes hand-in-hand with radical innovation. But broad economic volatility — inflation spikes, deep recessions — makes us more cautious, turn inward, and embrace a more populist “drawbridge up” economics. A recipe for stagnation.

This is where the Fed comes in. It’s the central bank's responsibility to aggressively respond to downturns while allowing expansions to continue until there is strong evidence of supply constraints and inflationary forces taking hold. So neither overreacting nor underreacting. It’s a hard job, which is one reason why Quarles and many Fed watchers have cautioned against putting more on the Fed’s plate, including fighting inequality and climate change. Helping support long, steady expansions that allow full societal participation in its economic benefits — well, that’s mission enough. And a successful execution of that mission is how the Fed can help support the growth and progress that could one day give America presence on the Red Planet.

Addendum: Apparently there’s something called the “Mars hypothesis” which posits the notion that “the Federal Reserve can set interest rates based on the movements of the planet Mars.” Now that would be a great subject for a speech from a Fed official or economist.

Long Read

📈 Did Goldman Sachs just make the case for a New Roaring Twenties?

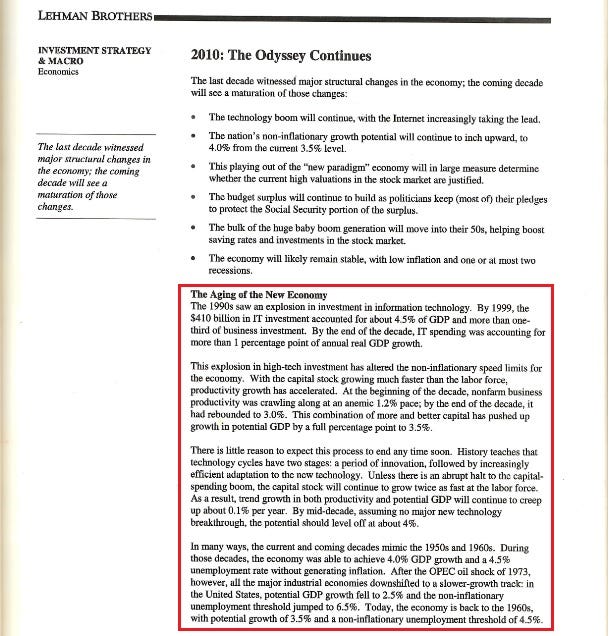

Back in 1999, enthusiasm and expectations were running high for the 21st-century American economy. This hyper-optimism was reflected in the surging stock market, of course. But also in Wall Street forecasts. One of my favorites is a December 1999 report from the investment bank Lehman Brothers titled “Beyond 2000.” In it, the firm’s economic team sketched out how they saw the next decade playing out. Beneath the headline “2010: The Odyssey Continues” was this super-bullish forecast, which I provide in full (outlined in red):

One hardly knows where to begin. But let me highlight two forecasts. First, there’s the comparison of the “coming decades” with the 1950s and 1960s, a period of rapid economic growth, low unemployment, and low inflation. It’s a period that today is often called a “golden age.” Does anyone feel we’ve been living in a golden age for the past 20 years? Second, and more importantly, Team Lehman thought the 1990s productivity boom was here to stay, which is why it also thought the economy could duplicate the strong performance of the 1960s with a potential, non-inflationary GDP growth rate of 3.5 percent.

Of course, Lehman Brothers — which didn’t even make it to 2010 — was wrong. Real GDP growth has averaged just 2 percent, with the tech-driven productivity boom fizzling by 2005. This is not a chart that many economists on Wall Street and in Washington would have expected:

Regular Faster, Please! readers know a frequent topic of this newsletter is an exploration of the possibility that another big productivity boom is approaching. Indeed, it may have been emerging must before the Covid-19 pandemic, as the chart suggests. And while the pandemic disrupted the economy here and globally, the emergence of work-from-home and greater e-commerce may add to that pre-pandemic trend.

But there’s more to it. In a recent report, Goldman Sachs highlighted three signs that suggest the underlying pace of measured productivity growth may now be accelerating (putting aside the controversy about whether government statisticians underestimate productivity growth).

First, there’s the possibility of total factor productivity, or TFP, mean reversion. TFP is often seen as a measure of technological progress and innovation — the ability to produce more valuable output with given quantities of capital and labor. GS notes that the rebound of TFP in the US fits in a long-term pattern extending back 140 years where TFP “growth appears stationary, with a variety of cycles of strength and weakness around an average annual growth rate of 1.2%.” If that pattern holds, further acceleration seems likely.

And this BLS chart shows just how important TFP growth (in red) is to overall productivity growth, and how big of a drag that missing TFP growth has been:

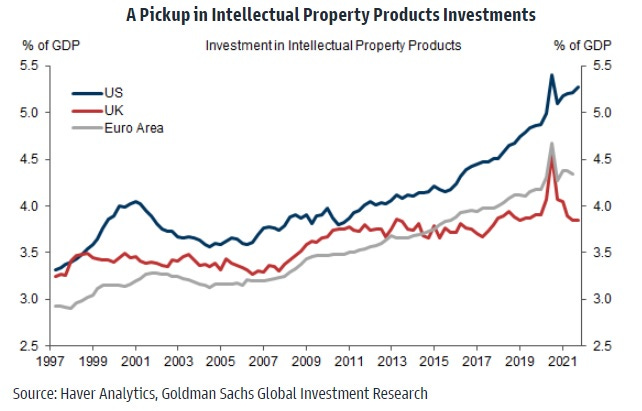

Second, a technological acceleration started before the pandemic. That might explain why TFP could be returning to trend. GS: “There is some evidence that technological acceleration, and potentially the second wave of the IT revolution, have contributed to the recent pickup in productivity growth. Investments in intellectual property products (IPP) had already started to rise before 2020 in the UK, the Euro Area, and especially the US, and surged in the first year of the pandemic.”

GS goes on to note a positive relationship between IP investment and productivity growth. Indeed, that connection would fit into a thesis from economist Erik Brynjolfsson that it takes time to see the productivity impact of game-changing technologies, such as AI: “In fact, productivity is initially suppressed as organizations invest time and effort creating intangible assets like new business processes, new skills, new goods and new services. However later, these investments are harvested, boosting productivity.”

Third, evidence of increased economic dynamism — specifically entrepreneurship and patents — bode well for future technology-driven productivity growth. GS:

New business applications surged in the US in mid-2020 and remain unusually high. France and Germany also experienced a significant but less dramatic pick-up in new business formation. Economic research suggests that a rise in entrepreneurship should boost productivity growth as new firms are an important source of innovation-driven TFP growth. Similarly, US patent applications have also risen sharply over the last year. The rise in applications has been particularly pronounced for patents in the “electricity” (e.g. electric equipment, broadcasting, wireless network) and “physics” (e.g. information and communication technology, computations) groups, which often cover fundamental inventions with longer-run productivity gains, and the usually more applied innovations in the “human necessities” (e.g. food, household appliances, entertainment) group with quicker productivity gains.

A few thoughts:

First, I love the notion of faster productivity growth. But given weak labor-force growth, we’re going to need TFP growth faster than the historical average to grow overall as fast in the future as we have in the post-World War II past. The long-term, 30-year Congressional Budget Office forecast assumes 1.1 percent TFP growth as part of its overall 1.8 percent real GDP forecast. That’s where emerging technologies such as AI, robotics, genetic editing, and more come in — though I don’t expect anticipation of their impacts to show up in these economic models.

Second, if you’re looking for a caveat to the GS optimism, I provided it a few weeks ago in another issue. I wrote how megabank JPMorgan saw little reason to think the post-pandemic economy will grow faster than the pre-pandemic one. If anything, it saw the risk being to the downside, describing trends in labor force growth, business investment, and worker skills as uninspiring. JPM also thought that for emerging technologies — like AI and robotics— to boost worker productivity, lots of complementary business investments would be necessary to realize that potential. That said, GS seems to think those investments may be starting to happen.

Third, productivity stats always tend to be volatile and are often subject to large revisions, and that’s especially been the case lately:

Finally, policymakers should assume the pessimists and skeptics are correct. Pro-growth policies should be a priority.