🚀 America is starting a New Space Age. And it's a problem that many Americans don't know about it.

The US is leading humanity toward bright future beyond Earth, but we need to be ready for costly setbacks.

You, my brilliant Faster, Please! readers, might be aware that NASA (along with SpaceX) is planning a manned Moon landing. Finally! But many — maybe most — Americans almost certainly aren’t aware. Some evidence of this comes via the May 4 broadcast of quiz show Jeopardy!

None of the three contestants responded with “What is Artemis?” (I was a 2002 Jeopardy! champ, by the way.) And I don’t think their problem was that they were confused by Jeopardy! getting the year wrong. Back in November, NASA announced the Artemis 3 mission was getting pushed back to 2025, a date many NASA watchers think is likely to get delayed again, especially given the hiccups with NASA’s expensive Space Launch System rocket. (It won’t be a reusable SpaceX rocket launching the crew, though the plan is for a SpaceX Starship to ferry the astronauts to the Moon.)

These SLS problems, not to mention decades of unfulfilled Washington promises about returning to manned space exploration, have no doubt played a role in the lack of public enthusiasm. As for the media, it’s been more concerned with the Billionaire Space Race, which it has frequently portrayed as a vanity space tourism project for the superduperrich. Some politicians, too.

But there’s lots of cool space stuff happening right now that’s getting too little play. For instance: Things seem to be proceeding apace with the final commissioning and tweaking of NASA’s $10 billion James Webb Space Telescope, launched last Christmas Day. Later this year, NASA’s DART (short for double asteroid redirection test) will run a planetary defense experiment by smashing into an asteroid in an attempt to slightly change its orbit around a bigger asteroid.

What’s more, the space economy may be moving beyond just the satellite industry. Blue Origin, the space company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is teaming up with other firms to build a space station in Earth orbit that would serve as a sort of office park to “generate new discoveries, new products, new forms of entertainment and global awareness of Earth’s fragility and interconnectedness,” as Blue Origin puts it.

Now in a better world, Artemis would be happening this year to take advantage of the 50th anniversary of the final Apollo mission in December 1972. And in an even better world, America wouldn’t have confined itself to low-Earth orbit for a half century. It would have kept space racing, if only against its own ambitions and dreams. (For what that might look like, I highly recommend the Apple TV+ show For All Mankind, whose third season debuts on June 10. I podcast chatted with creator Ronald D. Moore back in 2020.)

The business of space

But let’s stick to this timeline. It could be pretty awesome. A lengthy new Citi report, out today, expects the space economy to generate over $1 trillion in annual sales by 2040, up from around $370 billion in 2020. In “Space: Dawn of a New Age,” the bank said it expects the satellite market — currently 70 percent of the space industry, will continue to dominate, though new applications such as consumer broadband and satellite imaging will become increasingly important.

Driving the economics is perhaps the most underappreciated innovation since fracking: a massive decline in launch costs as the private sector — especially Elon Musk — got deeply involved in space. From the report (which supplies all the charts below):

Today’s launch costs of $1,500 per kilogram ($1,500/kg) are about 30x less than the launch cost of NASA’s Space Shuttle in 1981. Reusable rockets and launch vehicles, new materials and fuels, more cost-efficient production methods, and advancements in robotics and electronics systems are combining to drive these costs even lower. The authors of this report believe launch costs could to fall to $100/kg by 2040, and in a bullish scenario, to as low as $33/kg.

All that stuff is great. But what I find most exciting are the new industries that the decline in launch costs might spawn in coming years. Citi: “New applications are set to emerge and could generate $100 billion in revenue annually by 2040. Investment is also supportive as flows shift from being dominated by government agencies and the wealthiest nations, towards more private funding.”

Space industries of the future

Let’s briefly run through those sectors:

Commercial space station. Citi estimates NASA use of a private space station — and it’s not just the Bezos/Blue Origin venture trying to build one — could mean $3 billion in annual revenue, with new applications bringing another $5 billion.

Solar power from space. Citi thinks such systems would be comprised of reflectors or inflatable mirrors installed on satellites that would concentrate energy from the sun onto solar cells, with power then transmitted to Earth via either microwave or laser. A “rectifying antenna” on Earth would then capture that electromagnetic radiation, converting it into electricity and distributing it into the grid. In addition to declining launch costs, Citi’s $23 billion revenue forecast assumes “solar power continues to gain a strong share of total energy usage, expanding from ~3% currently to ~13% by 2040, the cost of solar power reduces at a compound annual growth rate of ~6% from ~$0.0068 per kilowatt hour (kWh) currently, and that space-based solar power grows to represent ~25% of all solar power by 2040, starting in 2024.”

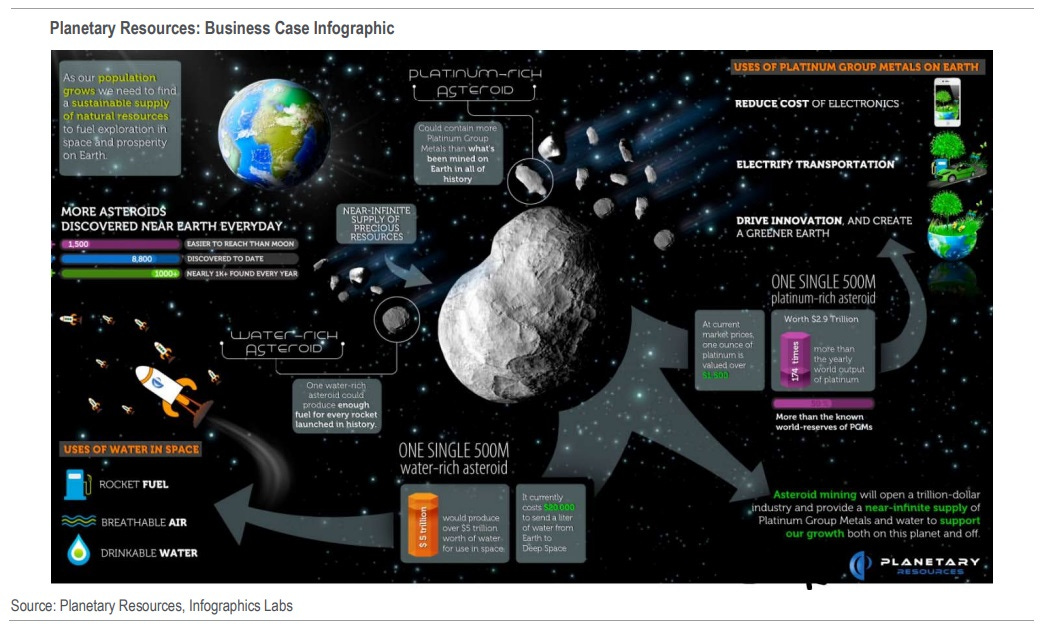

Asteroid mining. Citi cites numerous studies of potential asteroid riches, including a NASA estimate that the mineral wealth of the asteroid belt might exceed $100 billion for every person on Earth. Ultimate abundance. But the Moon will get mined before asteroids. Key lunar resources: water, helium-3, and rare-earth metals. From the report: “Our base case is that by 2040, mining water will be the initial focus given its value for additional space missions as a rocket propellant and importance for any colonization and industrial efforts in space.” Big challenges ahead, of course, as exemplified by the below chart from Planetary Resources, a space mining company that raised $50 million in 2016 but was unable to secure further funding in 2018. It was then purchased by a blockchain software technology company and its intellectual property placed in the public domain.

Space logistics. Citi’s bull case of $33 per kg or SpaceX’s target of $10 per kg would “make inter-city cargo rockets a much more attractive alternative versus current alternative modes of cargo transportation, in particular air freight, as a more premium and faster service … We estimate steady market-share

improvement from 2030 to 2040 to reach ~6% growth, giving us an annual sales

value of ~$20 billion.”

Space tourism and inter-city passenger travel. Citi: “As space becomes more ‘mainstream’ with more launches, lower launch costs, and better reliability/safety, we believe that it will become more accessible for the average person.” And that doesn’t just mean fun vacays in orbit. It potentially means much faster point-to-point travel around the planet. From the report:

We forecast the market for inter-city space passenger travel could be worth almost $7 billion of revenues for operators by 2040 assuming that it can capture ~20% of the long-haul business jet market by 2040. … On our base case for launch costs in 2040, we estimate that it would cost ~$100,000 to $200,000 for a long-haul inter-city rocket trip. With an occupancy of one to six passengers, this gives a range of $20,000 to $200,000 per ticket, with an average ticket price of ~$100,000. This compares to a Gulfstream G650 which costs ~$5,000 per hour, or $30,000 on a nearly six hour trip, and is typically flown with only one to two passengers. This makes inter-city rocket travel a viable premium alternative to long-haul business jet travel for ultra-high net worth (UNHW) individuals, with a much quicker travel time. … We forecast the market for space tourism could be worth $1 billion in revenues by 2040, assuming ~4,000 passengers a year travelling to the Karman Line (at a ~$50,000 ticket price), ~2,500 travelling to the ISS (at a ~$150,000 ticket price), and ~600 passengers a year travelling to the Moon (at a ~$650,000 ticket price). The Market Can Be 5x-10x

Microgravity R&D and construction. More than any of these other sectors, this is one where there probably will be use cases that we simply can’t imagine right now. But among the examples given by Citi: microgravity-produced silicon wafers, fiber optic cables, protein crystals to help companies conduct better and cheaper research to discover new proteins and drug treatments, and 3D-printing of artificial organs. Citi: “Assuming that microgravity R&D grows to represent ~4% of pharmaceutical R&D spend by 2040, while space-based construction grows to represent ~4% of heavy construction equipment (equipment used in mining, construction, manufacturing, oil and gas, public works and rail), we estimate a market value of $14 billion in annual sales by 2040.”

And beyond 2040? Citi: “Cheaper launch costs, and the corresponding increase in space infrastructure (e.g., on the Moon) and the increase in use cases for space, will mean that human missions to Mars are achievable in the next decade. SpaceX plans to fly a cargo Starship to Mars by 2024 and the first two-crewed Starship by 2026.” This SpaceX video is pretty good explainer about how that all might work.

Let’s not miss another chance at becoming a multiplanetary species

I call the techno-optimist 1960s era “Up Wing 1.0” and the 1990s “Up Wing 2.0” — both were periods of great enthusiasm about the ability of humanity to solve big problems. And that optimism was supported by a pro-progress culture. (Check out this essay for a longer explanation of my Up Wing thinking.) But we were unable to sustain those Up Wing attitudes and actions. A doom loop of unexpectedly slow progress, environmental catastrophism, cultural pessimism, lowered expectations, policy paralysis, and sheer economic ignorance slowly pushed Up Wing America into Down Wing mode

It’s my hope that we’re at the beginning of an extended period of technological progress, Up Wing 3.0. And developments in space are one reason for that. But hardly the only one. Lots of big progress in AI, energy, and biotech, too.

Yet space is particularly important for the inspirational role it can have in the public imagination. A space-faring humanity is one that has struck a major blow against the notion of resource scarcity as a factor limiting our species — not mention creating resilience against lethal space objects. America’s new efforts in space can be a powerful element in creating an optimistic image of the future. Especially at a time when so much of the present is disheartening — the lingering pandemic, economic volatility, war in Europe — it would be great for Washington to paint a comprehensive vision of what can come next.

There will likely be setbacks, even disasters, along the way. Americans need to know the effort will be worth it, despite the cost in blood and treasure. And we need to start that education by making sure they know the effort is even happening.

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples of those interviews:

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy