🦄 40 years later, 'Blade Runner's' dystopian economics still make zero sense

The film and its sequel depict incredible technological progress. So why is life shown as so implausibly awful?

Blade Runner, which premiered June 25, 1982, was a $30 million film that made just $41 million. So not a box office bomb, but definitely a financial disappointment. Director Ridley Scott was coming off a science fiction success in 1979’s Alien, and star Harrison Ford was by this time Harrison Ford.

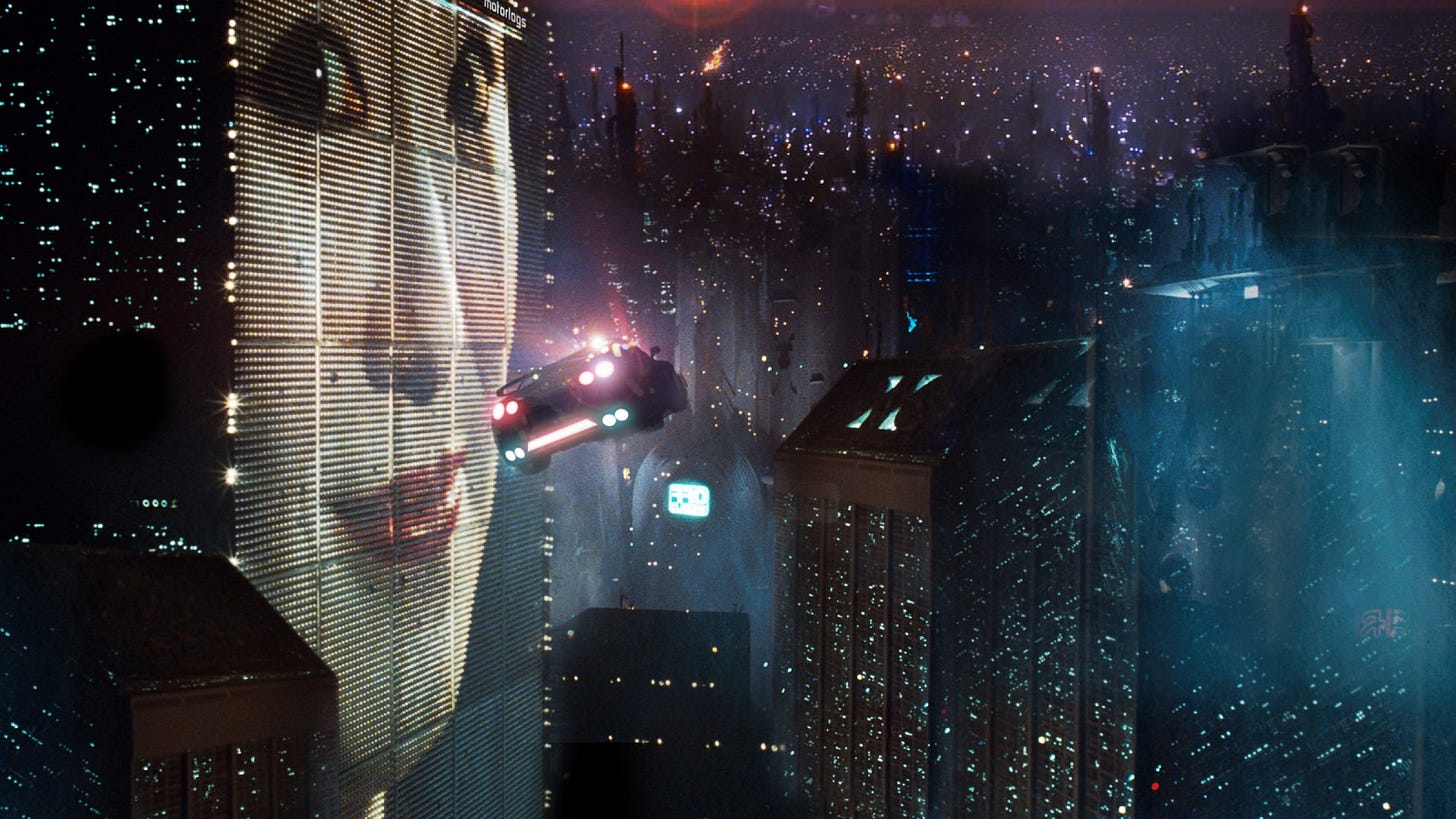

Instead of a rousing, action-packed blockbuster to rival the other big sci-film film that opened that month, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Scott delivered a dystopian art-house film that transports Sam Spade — Ford’s Rick Deckard — to a terribly polluted and inequality-riven 2019 Los Angeles where human “blade runners” hunt down bioengineered androids called “replicants.” It’s not raining in every scene, but every scene is raining noir.

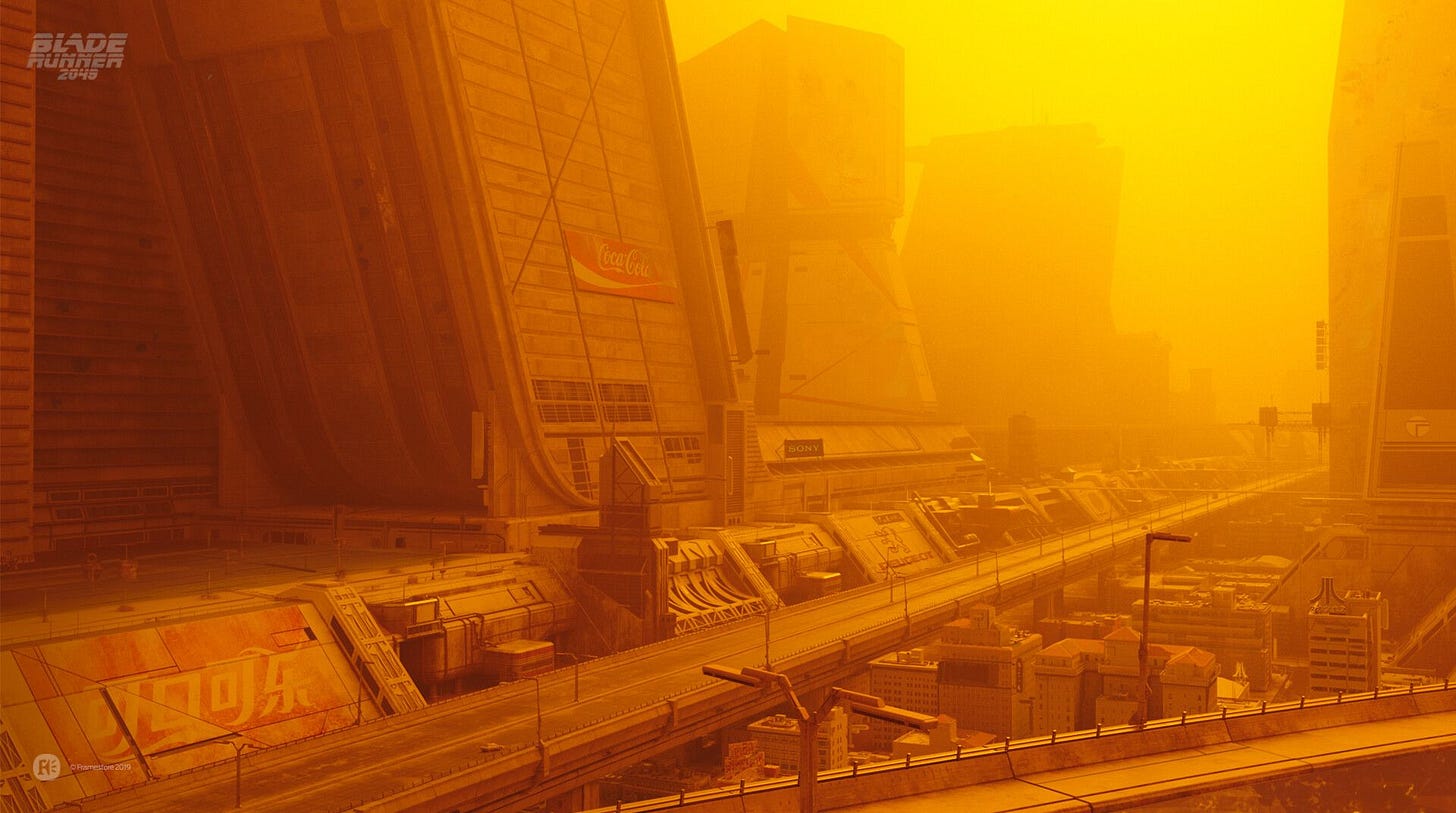

Of course, Blade Runner is now regarded as a film classic, sci-fi or otherwise, for its stunning visuals and deep meditation on a future that includes sentient, artificial life. And many fans and film critics find its sequel (also a box office laggard), the Denis Villeneuve-directed Blade Runner 2049 from 2017, to equal the original, both visually and intellectually. Count me as one such fan — and repeat viewer — of the two films.

But not once have I ever watched either film and thought, “This is what the future might actually be like.” The world-building, while cinematically and dramatically compelling, doesn’t add up — even assuming all of its futuristic technologies are possible. Indeed, that assumption undermines the verisimilitude of the world-building.

A universe of technological acceleration

Here’s what the Blade Runner-verse asks me to believe: The post-1960s Great Stagnation of tech progress — at least as it transfers into measurable business productivity growth — ends. (Or maybe never happens in that reality.) Humanity finally achieves many of the technological leaps anticipated by 1960s futurists and technologists: artificial general intelligence, sentient AI, bioengineered android bodies far more capable than human ones, off-world colonies across the Solar System, and flying cars propelled at least partially by anti-gravity technology (which also, presumably, helps enable space colonization).

Taken together, these impressive advances would seem to address two of the main arguments for techno-economic pessimism about the future. First, the great inventions of the past half century — mostly information technology — are simply less consequential than those of the previous century. Second, big game-changing ideas have become harder to find, requiring both more brains and bigger research budgets.

Let’s focus on AGI, or human-level AI. Achieving it would be arguably the most important scientific breakthrough in human history. In the previous issue of Faster, Please, I highlighted the new NBER working paper “Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work” by economist Anton Korinek and researcher Megan Juelfs, both of the University of Virginia. Korinek and Juelfs write that if “advanced AI and robotics can fully substitute for any type of human labor in the future … economic growth may increase significantly … by orders of magnitude.”

And it’s not just that some TeslaBot could work longer and more efficiently than its human counterpart. AGI would allow a nearly infinite number of brains to work on hard problems as super-research assistants. It would represent the invention of a new method of invention. As economists Philippe Aghion, Benjamin F. Jones, and Charles I. Jones write in “Artificial Intelligence and Economic Growth” (bold by me):

Artificial intelligence may be deployed in the ordinary production of goods and services, potentially impacting economic growth and income shares. But AI may also change the process by which we create new ideas and technologies, helping to solve complex problems and scaling creative effort. In extreme versions, some observers have argued that AI can become rapidly self- improving, leading to “singularities” that feature unbounded machine intelligence and/or unbounded economic growth

Where’s all the techno-solutionism?

Instead of one of the most famous cinematic depictions of a future dystopia, the world of Blade Runner should be one of dramatically greater wealth, health (there’s a historical correlation between tech progress and higher life expectancy), resources, and problem-solving capabilities. Replicants take most of the jobs? Here’s a pretty generous basic income for displaced human workers. Destructive climate change? Mega-machines to suck carbon out of the sky. Resource constraints? Asteroid mining. Population explosion? To quote an ad from the first film, “A new life awaits you in the off-world colonies. The chance to begin again in a golden land of opportunity and adventure.” Then again, life on Earth should also be pretty good for the Earth-loving remainers.

Even the two malevolent companies in the films, the Tyrell Corporation and the Wallace Corporation, suggest the continued existence of entrepreneurial opportunity in a world where companies such as Atari, Pan Am, and RCA continue to exist and thrive. That reality is another sign the economically volatile 1970s of our universe was probably a lot more prosperous in the Blade Runner-verse.

Economic growth versus inequality

But wouldn’t all the fruits of tech progress and faster economic growth go to a tiny elite? Certainly the films posit such an outcome. Not only are the replicants basically enslaved despite their sentience, but most of those humans not fortunate enough to emigrate to off-world colonies are stuck in a wet and dreary existence beneath towering corporate skyscrapers on a climate-shattered planet. (The CEO suite of the Tyrell Corporation might be the only spot in LA where you can see the sun.) It’s this image of the future that seems to drive many analyses of the film as a neo-Marxist cautionary tale of Late Capitalism.

Yet economic history suggests a far less dystopian future. For example: The consumption habits of the rich — automobiles, air travel, computers, giant TVs, smartphones — eventually becomes the consumption habits of everyone else. It’s not like Elon Musk has access to a better COVID-19 vaccine than I do. Indeed, what Musk is doing at SpaceX is a good example of this phenomenon. Its innovations are dramatically reducing the cost of space launches such that there is now a realistic path for regular people going to and living in space, not just the super-rich.

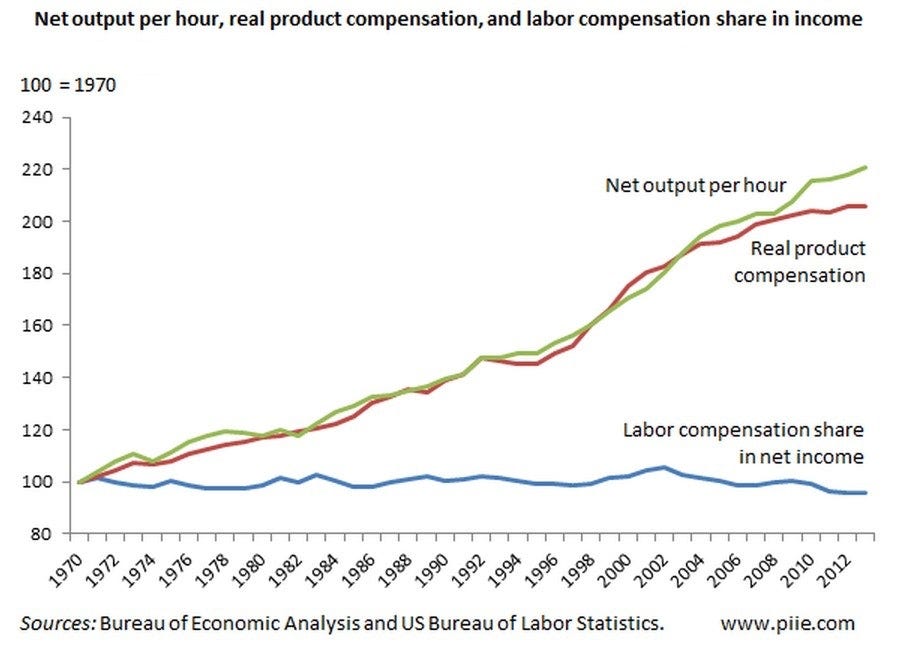

Economic history also suggests that even in a period of increased inequality, faster productivity growth boosts living standards.

Robert Lawrence of the Peterson Institute created the above chart a few years back. It shows a tight productivity-compensation relationship. It’s also worth noting that even though the Congressional Budget Office finds a roughly 25 percent increase in income inequality between 1979 and 2016, after-tax income measures show middle-class living standards up by 42 percent and 70 percent for the bottom fifth. Why exactly would economic relationships in the future be different other than for reasons of plot necessity?

Now there is one way in which the economics of these films make a bit more sense, though I doubt the filmmakers were thinking about it. During the early Industrial Revolution there was a period economists now call “Engel’s Pause” when output was expanding but living standards were stagnant. As AEI economist Michael Strain has described the period:

Real wages fell dramatically for some occupations. Many who held those occupations couldn’t be retrained to compete in the new economy. Lives were shattered. Some families suffered across generations. People flocked from the countryside to dirty, disease-infested cities. For decades there was deep social unrest. British society was shaken to its core.

And why aren’t things much better in the sequel? At some point between 2019 and 2049, the United States is struck by a massive electromagnetic pulse, an attack likely carried out by replicants. Perhaps that disaster extended the neo-Engels’ Pause. More likely, of course, Villeneuve simply wanted to further the original’s themes about capitalism, inequality, and the environment. (LA in 2049 is protected by a sea wall.) But those themes are utterly divorced from the economic reality likely generated by the tech progress of Blade Runner.

It’s my guess that our appreciation of Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 will only increase in the years and decades ahead. But that increased appreciation will more likely be driven by what the films say about human interaction with AI than about the flaws of capitalism.

Thanks for reading this far! Just a quick note for first-time visitors and free subscribers. In my twice-weekly issues for paid subscribers, I typically also include a short, sharp Q&A with an interesting thinker, in addition to a long-read essay. Here are some recent examples:

Economist Tyler Cowen on innovation, China, talent, and Elon Musk

Existential risk expert Toby Ord on humanity’s precarious future

Silicon Valley historian Margaret O’Mara on the rise of Silicon Valley

Innovation expert Matt Ridley on rational optimism and how innovation works

More From Less author Andrew McAfee on economic growth and the environment

A Culture of Growth author and economic historian Joel Mokyr on the origins of economic growth

Physicist and The Star Builders author Arthur Turrell on the state of nuclear fusion

Economist Stan Veuger on the social and political impact of the China trade shock

AI expert Avi Goldfarb on machine learning as a general purpose technology

Researcher Alec Stapp on accelerating progress through public policy