🤚 Yes, the pandemic-era school closures were a disaster

🔙 Thowback Thursday: Why 2022 wasn’t anything like the 2022 of 'Soylent Green' 😋

😱 Time has almost run out!

TODAY IS THE FINAL DAY!

Yep, this is the final day that all my wonderful free Faster, Please! subscribers can become annual paid subscribers at a monster 50% discount, or $30, from the regular annual price. I think it’s a really great deal.

With a paid subscription, you get full and timely access to all my pro-progress essays and podcasts, as well as the great 5 Quick Question Q&As with leading economists, technologists, policy analysts, and other smart people who also want to discover, create, invent, and build a better America and world.

Click the big blue buttons for more details!

Quote of the Issue

“The world has been oscillating between fears of two catastrophes — the population explosion and the atom bomb. Both pose a mortal threat. In this intolerable situation, with the menace of doomsday hanging over us, Dr. Borlaug comes onto the stage and cuts the Gordian knot. He has given us a well-founded hope, an alternative of peace and of life — the green revolution.” - Nobel presentation speech given in honor of agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug when he was awarded the 1970 Peace Prize.

The Mini-Essay

🤚 Yes, the pandemic-era schools closures were a disaster

I was going to make this issue of Faster, Please! a pure (and rare) “Throwback Thursday” edition given that the final week and final day of August is a pretty slow time for readership. But a new analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond changed my mind. I am going to briefly write about “The Pandemic’s Effects on Children’s Education,” a literature review by Santiago Pinto, a senior economist and policy advisor at the bank.

A brief reminder: Back in the summer of 2020, I tried to hammer home the point that preventing kids from going to school full-time and in-person during the coming school year would be a terrible idea with serious consequences for the kids and the country. School is more than just a place where younger students stay while their parents work, or a way for older students to get a certificate that helps them find better jobs. Deep economic research has shown that education really matters in helping kids grow into productive adults, including as workers in a complex, globalized economy. Those findings are seen to be as true today as when they were first identified in the 1950s. Indeed, a 2018 World Bank analysis shows the benefits increasing since 2000.

We now have a pretty good, albeit unsurprising, idea of the impact of the move to online learning and hybrid schedules. Here are some key takeaways from the Richmond Fed review:

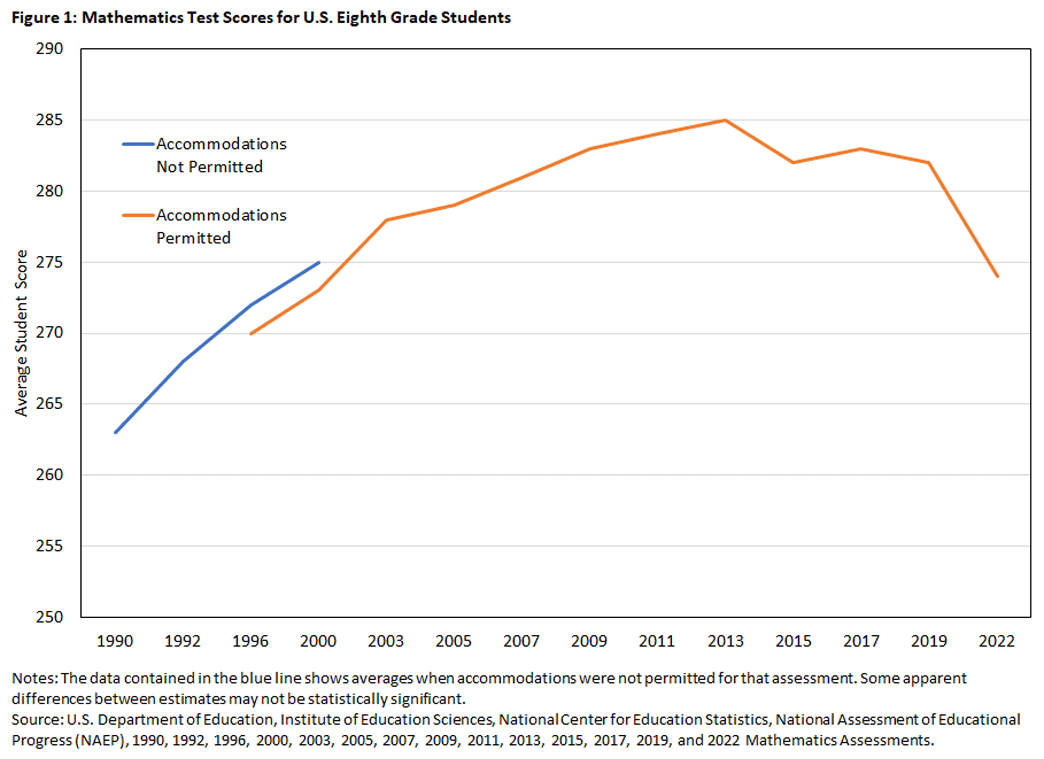

“Learning progress slowed substantially in the U.S. during the pandemic.” According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a test of U.S. eight graders, the average score of students rose by 20 points in the 30 years before the pandemic. But between 2019 and 2022, the average score went down by 8 points, which means that they lost almost half of what they had gained before.

“The amount of effective instructional time declined during the COVID pandemic period due to school closures and the sudden switch to remote learning.” That’s not good. Numerous studies find that temporary and unexpected changes in instruction time, such as school closures due to weather, strikes, or wars, affect student test scores. The consensus is that more instruction time improves student test scores.

“The schooling model — in-person, hybrid or virtual — also affects student achievement.” Also a bad result. Pinto points to two studies that examine the impact of different schooling modes during the pandemic on student test scores. “Pandemic Schooling Mode and Student Test Scores: Evidence From U.S. School Districts” finds that districts that offered more in-person schooling had smaller declines in math and English language arts pass rates than districts that offered less or no in-person schooling. (“The paper also shows that the positive effects of in-person learning were larger for students in lower grades.”) The second study, “The Consequences of Remote and Hybrid Instruction During the Pandemic,” shows that student achievement decreased as the percentage of remote instruction increased.

“School closures can also be expected to have consequences for the socioemotional and motivational development of children and adolescents.” No one should be surprised by this outcome: “Empirical evidence has linked school closures to several factors, including rising mental health concerns, lower levels of engagement, reports of violence against children, rising obesity, increases in teenage pregnancy, rising levels of chronic absenteeism and dropouts, and overall deficits in the development of socioemotional skills due to social isolation from networks and peers.”

There’s plenty more in the short paper, including, as I see it, how we are drastically underestimating just how thorough remedial “catch-up” efforts will need to be. Pinto’s conclusion:

School closures and switches to hybrid/virtual learning due to the pandemic adversely affected student achievement through several channels, including a decline in skill accumulation and a disruption of peer effects and peer-group formation.

Preliminary evidence suggests that losses took place early in the pandemic and that there has not been an apparent recovery. Also, the impact on students has been far from uniform, as economic losses tend to fall more deeply on younger students and students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Simply returning schools and instructional practices to where they were prior to 2019 will not avoid such losses. A wide range of remediation policies has been suggested, and evidence suggests that instruction practices — such as tutoring and individualized/small group instruction — appear to be effective.

School disruptions and learning losses have a wide range of economic and social effects. Lower levels of learning due to fewer years of effective schooling translates into deficient development of cognitive skills (measured by scores in standardized tests). In turn, lower cognitive skills will likely reduce the future earnings potential and labor-market opportunities of the students affected. All of this could eventually translate into lower economic productivity for the nation as a whole.

Keeping kids in school was a national emergency worthy of massive funding and massive policy imagination. Now we’re living with the failure to treat school closures as the tragedy that it was. And we’re going to be living with the long-term impacts for decades.

🔙 Thowback Thursday

😋 Why 2022 wasn’t anything like the 2022 of “Soylent Green”

I wrote the following essay last year since 2022 was the year in which the dystopian film Soylent Green took place. The film, however, was released in 1973 — a key year that marked the end of America’s postwar productivity boom — so consider this replay a 50th anniversary tribute of sorts to the pessimistic masterpiece.

Recall the tagline in Apple’s famous “1984” commercial — the one that opens with the javelin thrower pursued by stormtroopers — introducing its new Macintosh computer: “. . . you'll see why 1984 won't be like ‘1984.’” It was the perfect match of savvy marketing with a significant moment. We had arrived at the year that supplies the title of George Orwell’s vision of a totalitarian nightmare world, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

We’ve now arrived at another key moment in the timeline of dystopian science fiction. In two days, it will be 2022, the year that provides the then-futuristic setting for Soylent Green. (Next up: Children of Men in 2027.) Watching the 1973 film is like opening a cinematic time capsule filled with the era’s post-Silent Spring ecological anxieties. It’s all there: Overpopulation, hunger, global warming and oppressive humidity, stark inequality, depleted natural resources, widespread euthanasia — not to mention a solid performance by Charlton Heston as our laconic guide through this hellscape of sticky squalor. Unlike Nineteen Eighty-Four, however, Soylent Green is clearly meant as a warning about the miserable shape of things to come. In the 2018 essay “Malthus at the Movies: Science, Cinema, and Activism around Z.P.G. and Soylent Green,” Jesse Olszynko-Gryn and Patrick Ellis write that Heston was concerned about overpopulation and used his star power to get Soylent Green made. The script was loosely based on Make Room! Make Room!, a 1966 science fiction novel by Harry Harrison that had quickly come and gone:

Heston was particularly concerned with overpopulation, a then bipartisan issue supported not only by leftwing environmentalists, but also by Republican conservationists and conservative anti-immigration activists. According to his biographer, Soylent Green was “the only film that Heston made with the express purpose of advancing a political message. . . . Heston was able to push Harrison’s novel through the studio system, but only after the commercial success of Skyjacked, in which he starred. Initially, he and producer Walter Seltzer invested their own money to have a screenplay written, but MGM was “wary of tackling [. . .] over-population — no doubt for fear of stepping on religious toes.”

So why isn’t 2022 for us going to be anything like the 2022 of Soylent Green? Well, the pessimists back then got a lot wrong.

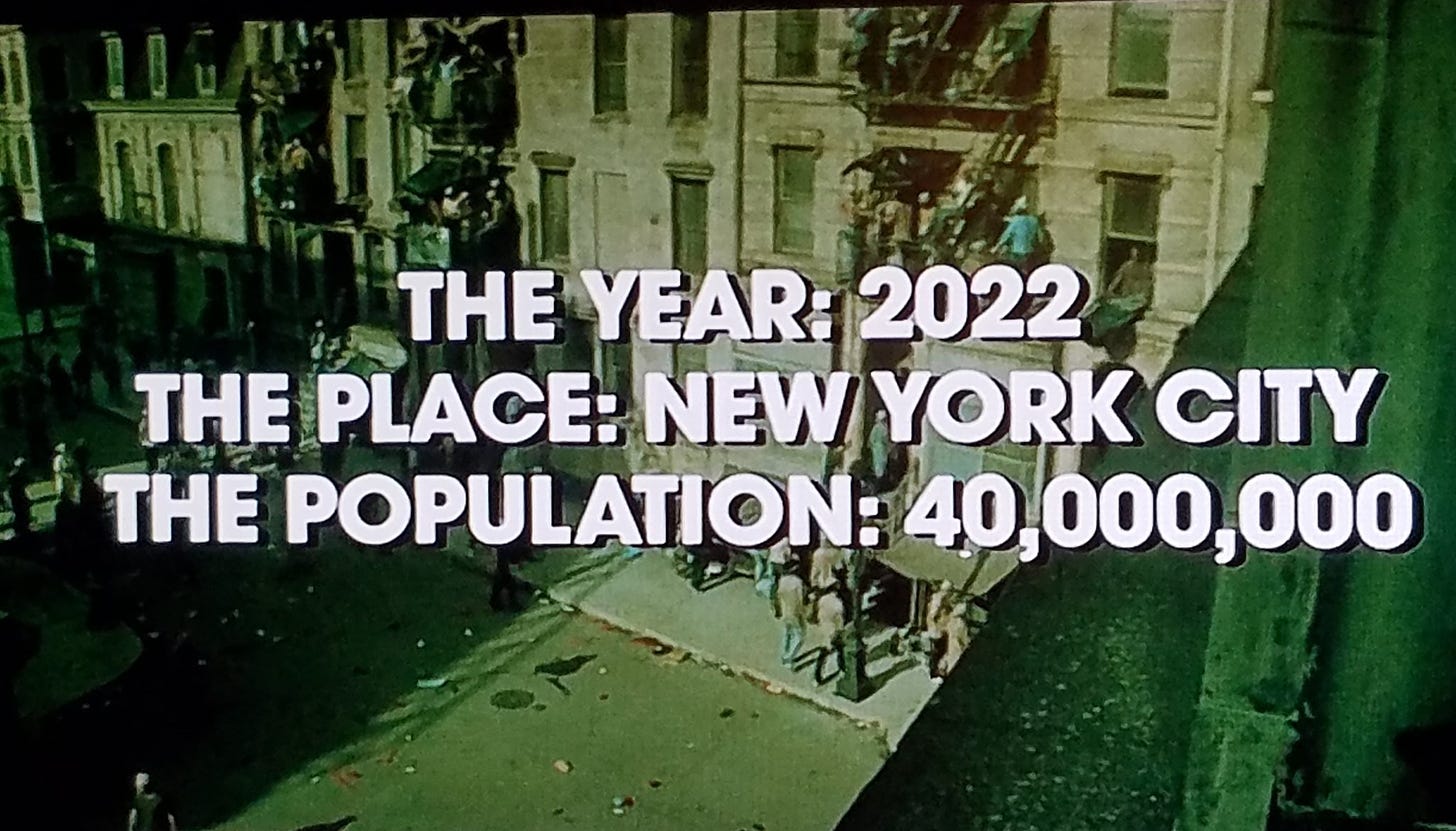

They failed to grasp the “demographic transition” when people in rich countries start having fewer kids. The average fertility rate in at least moderately rich countries is now just 1.6, well below replacement. Today’s population-related anxiety is about too few of us, not too many. Oh, and the Big Apple is less than a quarter of the size predicted in the above image from the film’s opening.

The Green Revolution — the creation of high-yielding crop varieties and new agronomic techniques — caused a huge increase in agricultural productivity. No need for the film’s eponymous foodstuff.

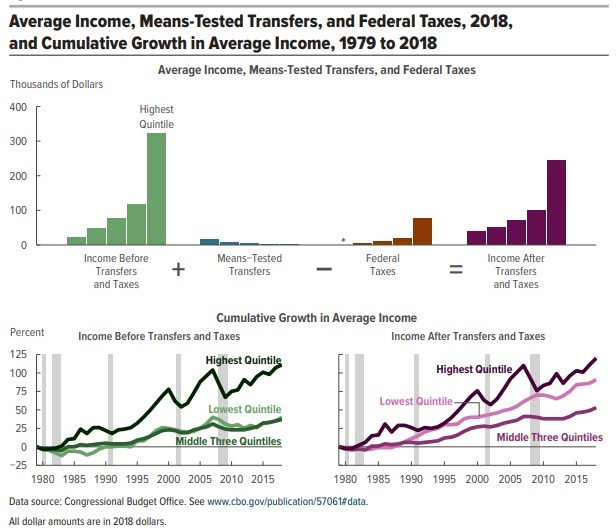

A turn toward market economics led to huge drops in poverty and hunger in Asia, especially in China and India, which also reduced global inequality. And while US income inequality is greater today than in the 1970s, all income groups are better off today than back then:

Finally, as always, the ingenuity that democratic capitalism allows and enables meant we learned to do more with less. When the price of resources rises, we search harder for more of that resource and for substitutes. Tomorrow is rarely like today thanks to invention and innovation. For example: The notion of Peak Oil became a punchline thanks to the Shale Revolution. Another example: the Julian Simon-Paul Ehrlich wager of 1980 over resource scarcity, won by the former when the prices of copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten all declined over the subsequent decade. And in the excellent More from Less, Andrew McAfee cites research finding a “dematerialization” of the American economy since the early 1970s with a decline in the absolute consumption of key commodities such as steel, copper, fertilizer, timber, and paper. “Total annual US consumption of all of these had been increasing rapidly in the years prior to Earth Day.” As McAfee explains:

We invented the computer, the Internet, and a suite of other digital technologies that let us dematerialize our consumption: over time they allowed us to consume more and more while taking less and less from the planet. This happened because digital technologies offered the cost savings that come from substituting bits for atoms, and the intense cost pressures of capitalism caused companies to accept this offer over and over. Think, for example, how many devices have been replaced by your smartphone.

Of course, we have more to do. Still too many poor people and hungry people. Still too many of us unable to more fully realize our human potential. But looking at why 2022 isn’t 2022 should give us some hints at how to better create a better future.

Micro Reads

How China became the king of new nuclear power, and how the U.S. is trying to stage a comeback - Catherine Clifford, CNBC |

Chinese ChatGPT alternatives just got approved for the general public - Zeyi Yang, MIT Tech Review |

UAE launches Arabic large language model in Gulf push into generative AI - Simeon Kerr and Madhumita Murgia, FT |

Super-heavy oxygen hints at problem with the laws of physics - Karmela Padavic-Callaghan, New Scientist |

Non-gas giant has 73 times Earth’s mass, bewildering its discoverers - John Timmer, Ars Technica |

Biden’s Trumpist Trade Policy - Inu Manek, WSJ Opinion |

US District Court Rejects AI-Generated Content as Not Copyrightable - Michael Rosen, AEIdeas |

The Moon Needs a Power Grid - John Landreneau and Lauren Schricker, IEEE Spectrum

The Age of Prediction — where will algorithms take us? - Felix Martin, FT |

Beating climate change absolutely requires new technology - Matthew Yglesias, Slow Boring |

Faster trains to begin carrying passengers as Amtrak’s monopoly falls - Luz Lazo, WaPo |