↘ Will the US be weaker in 2050 than today?

Most Americans think so. Here's why I don't.

Quote of the Issue

The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.” - Walt Whitman

The Essay

↘ Will the US be weaker in 2050 than today?

I guess I’m deeply in the minority when it comes to how I view America’s future. Here are some gloomy numbers from a new Pew Research survey:

Sizable majorities of U.S. adults say that in 2050 – just over 25 years away – the U.S. economy will be weaker, the United States will be less important in the world, political divisions will be wider and there will be a larger gap between the rich and the poor. Far fewer adults predict positive developments in each of these areas:

To paraphrase Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi, everything those big majorities believe is wrong. The economy will be stronger. The US will be more important in the world. The country will be more politically unified. And the gap between the rich and the poor will shrink.

A solar-flare level hot take? Well, let me put it this way: I think my more positive outlook is more likely than not, especially if I only can choose between boom and gloom. I guess a more nuanced summary of my views it that many positive trends are being downplayed. Moreover, better policy decisions today can further encourage those good trends and counteract many bad ones. Let’s examine each of those declinist views that Pew found:

➡ “The US economy will be weaker in 2050.” The bullish case here is that the American economy stands to benefit from an emerging cluster of technological innovations — including in biotech, energy, robotics, and space — with AI-machine learning holding perhaps the most potential as a productivity-boosting general purpose technology with impacts across business sectors: energy, finance, health, marketing, media, professional services, and retailing. As I noted in the previous issue of this newsletter, ChatGPT from Sam Altman’s OpenAI is being tested by nuclear fusion startup Helion, also an Altman investment, to see if the large language model can accelerate engineering work. Then there are the early studies showing huge productivity gains in areas such as coding and customer service. But even before ChatGPT became a thing, machine learning was already being employed in areas such as drug discovery and materials science. And while technological progress may have its own inherent momentum — “Technology happens because it is possible,” as Altman has put it — our actions matter. Are we going to think hard about the impacts of our investment, regulatory, and tax actions on innovation? If the US economy is weaker a generation from now than it is today, America as a society will be able to look in the mirror to discover the reason why.

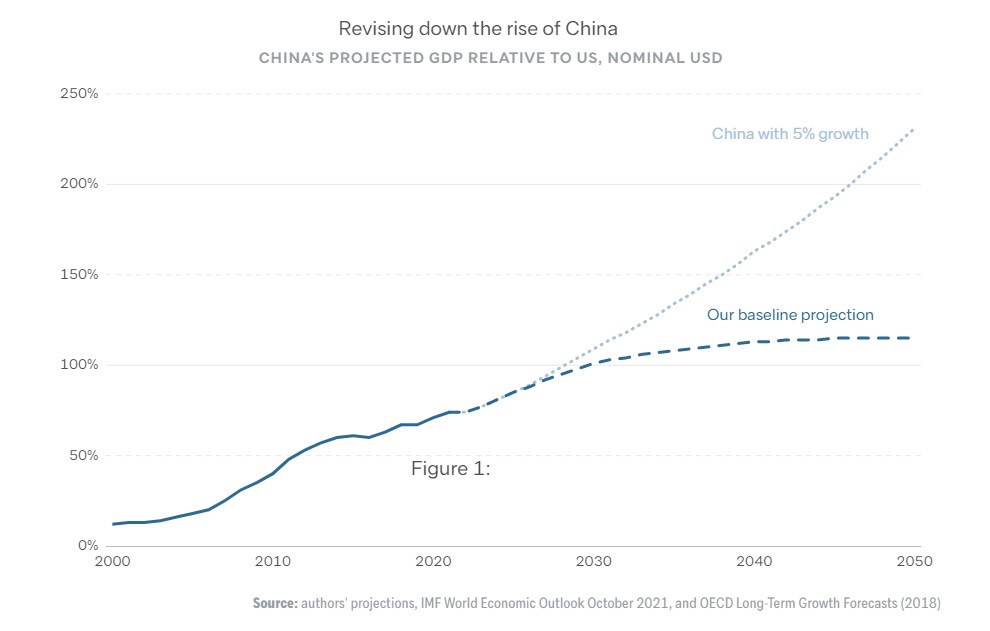

➡ “The United States will be less important in the world.” Compared to whom? Not Europe, which seems to view its comparative advantage as creating innovation-stifling regulation rather than creating new technologies and their commercial applications. If you look at the 25 largest technology companies by market cap, 18 are American, just two European (and none in the top ten). In terms of national wealth, America continues to extend its lead. From The Economist: “Income per person in America was 24 percent higher than in western Europe in 1990 in PPP terms; today it is about 30 percent higher. … A trucker in Oklahoma can earn more than a doctor in Portugal. … Britons, some of Europe’s best-off inhabitants, spent 80 percent as much as Americans in 1990. By 2021 that was down to 69 percent.” But won’t America diminish in global power versus China? Consider this: China is facing a stark demographic near-future with its current population perhaps falling by half over the few decades to 700 million from 1.4 billion. The working-age population is already shrinking. And productivity growth? Moribund, thanks to its turn away from liberalization. Even if China can grow at 2 or 3 percent long term, concludes a recent report from Australia’s Lowy Institute, “it would never establish a meaningful lead [in economic size] over the United States and would remain far less prosperous and productive per person than America, even by mid-century.”

➡ “The country will be more politically divided.” Here’s an interesting hypothetical: What if the late 1990s economic optimists had been correct, and the internet bubble had turned into a lengthy economic and productivity boom as was seen in the immediate postwar decades? Remember, the US productivity slowdown began before the Global Financial Crisis. So, even assuming the GFC still happened, the post-GFC recovery might well have been much, much stronger under this scenario — and our politics less brutal. Sure, 1990s politics seemed pretty contentious at the time. I mean, the GOP-controlled House impeached President Clinton. Yet Clinton served two terms, including by a near landslide in 1996, and as 2000 began, 69 percent of us were satisfied with the direction of the country. Do you know what brings out the worst in us? Tough economic times. Financial crises, in particular, seem to be drivers of populism. So avoiding big financial shocks and deep recessions is a good thing, as is making sure the underlying economy maximizes its potential during the good times. Now none of this is to say that rapid growth doesn’t cause dislocation. Creative destruction and all that. But this is another area for policy, whether its better worker retraining, helping workers move to where the jobs are, or intervening to directly boost wages through earnings subsidies if we go through a period where automation has a large negative impact on labor markets.

➡ The gap between the rich and poor will grow. The narrative of exploding inequality has clearly been deeply imbibed by the general public. But what are the facts? As my AEI colleague Michael Strain observes:

The CBO computes the size of the gap between higher- and lower-income households using a standard statistical measure that accounts for the entire distribution of income (the “Gini coefficient”). While inequality of post-tax-and-transfer income did rise by 7% from 1990 to 2019, all the increase occurred between 1990 and 2007, before the explosion of political and media interest in inequality. Since 2007, inequality has fallen by 5%.

It’s worth noting that the early studies on GenAI make it far from obvious that this new technology will boost inequality rather than have a leveling effect. For example: In the new working paper “Generative AI at Work” by Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, and Lindsey R. Raymond, the researchers look at the impact of large language models on customer service agents, finding “suggestive evidence that AI assistance leads lower skill agents to communicate more like high-skill agents.” Likewise, the working paper “Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence” finds that the use of ChatGPT in professional writing decreases inequality between workers.

Bottom line: My bias is towards optimism, but it’s a bias that has a foundation in fact, not wishful thinking. And the more Americans I can persuade to share that optimism, the more likely it will become a self fulfilling prophecy if that attitude leads to pro-progress actions.

Micro Reads

▶ ChatGPT is going to change education, not destroy it - Will Douglas Heaven, MIT Tech Review |

▶ The Quest for Longevity Is Already Over - Matt Reynolds, Wired |

▶ ChatGPT’s Secret Weapon Is Artificial Emotional Intelligence - Parmy Olson, Bloomberg Opinion |

▶ Elon Musk discusses artificial intelligence with Sen. Schumer - WaPo |

▶ Skunk Works Reveals Progress on NASA's Secret Supersonic X-Plane - Sascha Brodsky, PopMech |

Nice one!