✨ The future of AI and the US economy, according to Goldman Sachs

The bank expects productivity gains from AI to boost growth, just not so far

“Productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” - Nobel laureate Paul Krugman.

Goldman Sachs has been perhaps the most high-profile Wall Street bank for thoroughly analyzing the emerging impact of artificial intelligence, especially generative AI since 2022, on future US productivity and economic growth. GS is out with a new analysis, “The Productivity Outlook: Back to the Future,” which is super interesting and informative.

In this new report, GS addresses the AI issue and the broader trend of 21st-century American productivity growth. (This subject is one of the major themes of my 2023 book, The Conservative Futurist.)

I'm going to lead with my major takeaway: This isn’t a prediction of Technological Singularity. GS is a major financial institution, not an e/acc enthusiast on social media. It offers a relatively cautious but reasonable forecast that, in effect, assumes a future AI productivity impact comparable to the PC + internet combo. This makes for a sensible but hardly unexciting baseline.

But you should remember that based on my reading of this GS analysis and previous ones (which I summarize later), there’s plenty of upside economic room if GenAI proves to be an utterly paradigm-shifting technology. (Did someone say “AGI?”) As GS notes in an earlier report:

Many commentators believe this is a possibility, particularly if generative AI models progress to a point where they are able to innovate on their own and accelerate the pace of idea generation. … Some commentators view recent advancements in generative AI models as a meaningful step towards a “superintelligence” that is able to process information, formulate views, and innovate beyond the capability of humans. For now, we see such predictions as very premature, especially given the well-documented limitations of current AI models, including a tendency to “hallucinate” false information. We therefore maintain our view that for the foreseeable future, generative AI will mostly drive efficiency gains by automating less difficult but time-consuming tasks, thereby empowering workers to engage in more productive activities. Under this assumption, the impact of generative AI should more than offset the empirically-validated productivity growth slowdown that would likely prevail in a non-AI baseline, but will provide a transitory rather than permanent boost to growth.

A few numbers to keep in mind as I go through the GS analysis:

US real GDP growth has averaged 3.1 percent in the postwar era, including a slower 2.1 percent in the 21st century.

US productivity growth (output per hour worked) has averaged 2.1 percent annually in the postwar era, though far slower since the 1973 Great Downshift.

US total factor productivity — economic shorthand for an economy’s innovativeness — grew at 2 percent a year before the Great Downshift, accounting for two-thirds of overall productivity growth). Over the next quarter century, TFP growth slowed significantly to just 0.5 percent annually. The tech boom from 1995 to 2004 saw a resurgence in TFP growth, reaching 1.8 percent annually. But since 2004, TFP growth returned to its sluggish post-1973 pace.

This CBO chart gives a sense of how important labor productivity is to overall GDP growth.

So: GS calculates that labor productivity growth declined from its long-term average of 2.25 percent to about 1.5 percent annually between 2007 and 2019. This slower pace has continued since 2019. While BLS reports show a 2.7 percent increase in productivity over the past year, GS thinks the figure may be inflated due to downward revisions in output growth and potential issues with how work hours are calculated in productivity statistics. (Yikes.)

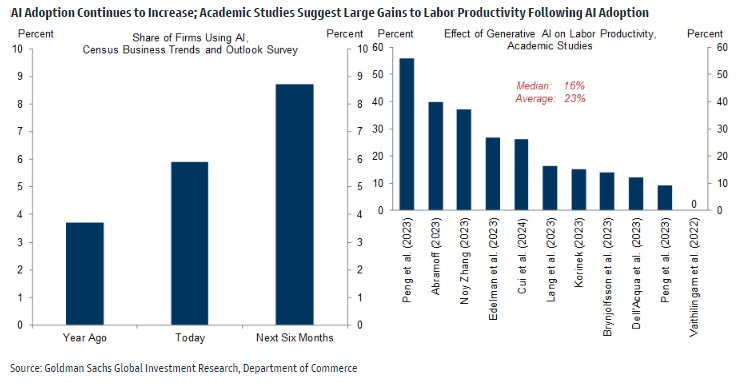

Going forward, the bank forecasts a productivity growth slowdown to about 1.7 percent in the near term. By the late 2020s, however, it anticipates AI will boost this by roughly 0.4 percentage points. The bank cites early academic research and corporate data that indicate AI significantly enhances productivity. The extent and timing of its impact, however, will depend on how AI technology develops and is adopted. That’s really the ballgame, here.

GS attempts to answers a few key questions:

➡ Why was productivity so slow during the past pre-pandemic business cycle? The bank offers a multi-causal explanation, noting that most of the slowdown was due to slower growth in TFP. First, it's becoming increasingly difficult to make significant tech advancements. Example: Moore's Law, where maintaining the rate of progress in computer chip density has required an ever-growing number of researchers. Second, there was a slowdown in the dynamic reallocation of labor and capital from less efficient to more efficient firms. (Some economists point to declining competition.) Third, an increasing share of economic activity has shifted towards hard-to-measure digital goods and services, which may not be adequately captured in GDP calculations. (This could have resulted in understated productivity growth, actually.)

➡ Why has productivity growth accelerated since the pandemic? There’s been a surge in business applications and formation, particularly in the most productive technology sectors. High-tech business creation has outpaced low-tech. And although growth rates have converged recently, “the level of high-tech new businesses remains sharply higher than before the pandemic.”

Good news, then: Past productivity booms were often preceded by increased entry in high-productivity industries. Bad news: “The pandemic caused some disruption to school enrollment and educational achievement. Based on estimates of the effects of schooling on worker earnings, we expect these changes to result in a 0.1pp drag on labor productivity over the next several years.” (Quite predictable.) As for remote work, impact of increased remote work on productivity growth “remains unclear,” according to GS< with studies estimating effects that range from an 18 percent decrease to a 13 percent increase

Then there’s this, which is not great:

Over the last year, nonfarm business productivity growth accelerated to 2.7%, leading some commentators to wonder whether the US economy is on the cusp of a more sustained productivity boom. We think it is premature to infer much from the recent strength, for three reasons. First, because nonfarm business output growth was revised down by a little over 0.3pp over the last year, and this hasn’t yet been incorporated into the productivity statistics. The revision to output growth more than offsets the part of the preliminary downward revision to payroll growth that we attribute to a genuine overstatement of employment growth in the establishment survey, rather than the removal of unauthorized immigrants from the payroll statistics. Second, because we think part of the acceleration is an overstatement caused by the likely mismeasurement of hours in the productivity statistics. After adjusting for these two factors, productivity growth over the last year was around 2%, in line with its 2019 pace.

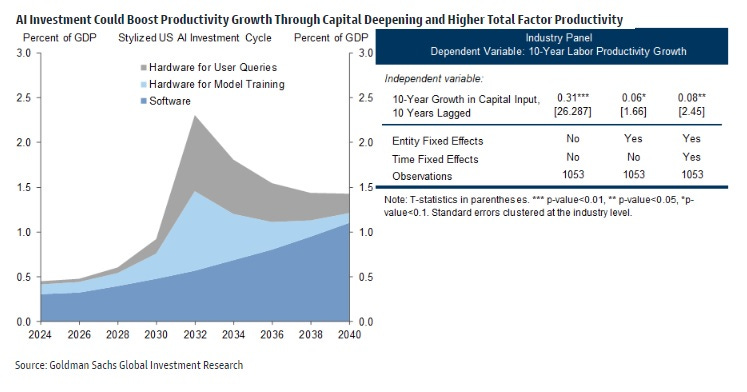

➡What about the economic boost from AI? Here were go: “Later this decade and in the early 2030s, we expect productivity gains from AI to boost GDP growth by around 0.4pp. Even before AI provides its peak boost to TFP growth, it is likely to boost labor productivity by increasing the amount of capital per worker.”

Granted, AI's impact on the overall economy is still relatively small right now. But more companies are starting to experiment with and deploy the technolgy. Early studies and reports from businesses already using AI suggest it can significantly increase worker productivity. And a 0.4 percent boost to basically restore our postwar productivity average is nothing to sneeze at — though I sure hope for more.

For now at least, even as Silicon Valley dreams of singularities, Wall Street sees AI as a pragmatic fix for America's productivity woes. It’s a start, with maybe more to come.

How we got here since 2022

Finally, as promised. here’s a recap of what the bank has been saying about GenAI over the past year and a half.

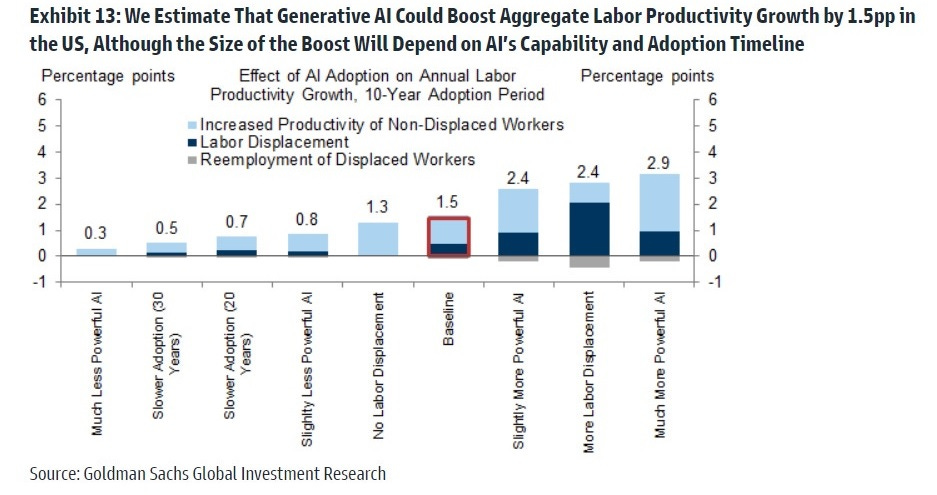

In March 2023, the GS economics team called GenAI “a major advancement with potentially large macroeconomic effects,” estimating the technology could eventually “raise annual US labor productivity growth by just under 1½ [percentage points] over a 10-year period following widespread adoption.” (I wrote about that analysis here.)

In October 2023, GS reiterated that the economic potential of generative AI was "enormous," although the net effect in the near term might be smaller due to potential overlaps with other tech-driven productivity gains (the ongoing Digital Revolution) and the slowing trend in underlying productivity growth (big ideas are getting harder and more expensive to find). Also: History suggests delays of a decade or more in the widespread adoption of game-changing tech, such as electrification, computers. (I wrote about that analysis here.)

In April of this year, GS updated the status of the AI transition, finding it ”well underway” as evidenced by massive increases in AI-related investment and productivity gains among early adopters. That said, a “slow adoption pace suggests that sizable macroeconomic impacts are still several years off.” (I have written about GS’s quarterly updates on investment and adoption, most recently here.)

In June, Jim Covello, head of GS global equity research, got some media attention by questioning the transformative potential of GenAI. Covello argued that AI must eventually solve complex problems to earn an adequate return on the trillion-dollar cost of developing and running the technology. But he expressed deep skepticism about whether capabilities would rise or costs fall enough to justify the investments or investor enthusiasm: “... eighteen months after the introduction of generative AI to the world, not one truly transformative—let alone cost-effective—application has been found. .. I don't think the technology is, or will likely be, smart enough to make employees smarter.” (I wrote about that here.)

In September, GS published a global strategy that concluded “the technology sector is not in a bubble and is likely to continue to dominate returns.” The theory of the case here is that new technologies like GenAI will attract gobs of investment but also generate lots of creative destruction with companies failing. “So, while the leading tech companies of the 2020s will most likely remain dominant in their respective markets, rapid innovation, particularly around machine learning and AI, will likely create a new wave of tech superstars and possibly products and services that are not yet imagined.”(I wrote about that here.)

Micro Reads

▶ Economics

Three Receive Nobel in Economics for Research on Global Inequality - NYT

The Economist Whose Contrarian Streak Has Gotten Attention in Biden and Trump Camps - WSJ

Worldwide Efforts to Reverse the Baby Shortage Are Falling Flat - WSJ

▶ Business

U.S. Tech Firms to Invest More Than $8 Billion in U.K. Data Centers Amid AI Frenzy - WSJ

SpaceX Launches Starship Rocket and Catches Booster With Mechanical Arms - NYT

The Cutting-Edge Hearing Aids That You May Already Own - The New York Times - NYT

▶ Policy/Politics

▶ AI/Digital

▶ Biotech/Health

▶ Clean Energy/Climate

A utility promised to stop burning coal. Then Google and Meta came to town. - Wapo

Experiments Show Harnessing Energy from 'Superhot' Rocks Deep Underground is Now Possible - The Debrief