🤖👶 Reversing the global fertility collapse: Tech progress might be the only answer

AI-driven economic growth might give workers the wealth, time and desire to choose bigger families

Quote of the Issue

“We should strive to welcome change and challenges, because they are what help us grow. With out them we grow weak like the Eloi in comfort and security. We need to constantly be challenging ourselves in order to strengthen our character and increase our intelligence.” - H.G. Wells, The Time Machine

The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised

“With groundbreaking ideas and sharp analysis, Pethokoukis provides a detailed roadmap to a fantastic future filled with incredible progress and prosperity that is both optimistic and realistic.”

The Essay

🤖👶 Reversing the global fertility collapse: Tech progress might be the only answer

Summary: The global trend of declining fertility rates is expected to have immense implications for societies and economies. While some argue for policies to boost fertility, such efforts may be futile given the trend's power and scope. But there are alternative scenarios that could lead to higher fertility rates, such as shifts in societal norms or tech-driven economic growth. Despite concerns about widespread "workism" and its supposed negative impact on family formation, AI-driven economic growth could greatly reduce work hours in the long run, allowing for more leisure time and and increasing the desire for larger families. Faster, please!

It’s the Mother of All Demographic Trends. Well, maybe that’s the wrong language to use given that the trend is about mothers and fathers wanting fewer kids — or adults not wanting to be moms and dads at all. According to a study of 204 countries and territories forecasts published Wednesday in The Lancet, 76 percent will fall below population replacement rates by 2050, with that number rising to 97 percent by 2100. “The implications are immense,” said Natalia Bhattacharjee, co-author of the study. “These future trends in fertility rates and live births will completely reconfigure the global economy and the international balance of power — and will necessitate reorganizing societies.”

All sorts of long-term implications here, including fewer younger people to support and care for older people, and fewer workers to produce goods and services. This, too: an entirely different societal vibe. As a midwife says in Children of Men, a dystopian film about a childless future, “As the sound of the playgrounds faded, the despair set in. Very odd what happens in a world without children's voices.”

Of course, falling global fertility rates are hardly news. But I would guess that many people underestimate the power and momentum of this trend. When my AEI colleague and University of Pennsylvania economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde calculates global fertility rates, he finds them “falling much faster than anyone had realized before.” His 2021 co-authored paper "Demographic Transitions Across Time and Space" highlights that the global demographic shift from high to low fertility is occurring in almost every country, with the transition accelerating due to increased global connectivity and access to information about smaller family sizes, healthcare, and education.

In short: Millennials and younger Gen Xers in America will likely witness the beginning of a long-term decrease in human population, an unprecedented event for Homo sapiens. Is this necessarily a bad thing, though? Experts less confident than I in humanity’s ability to a) generate material and energy abundance, b) innovate our way out of the biggest harms of climate change, and c) spread across the Solar System would argue that the quicker we get a stabilized — and then declining — population, the more sustainable industrial civilization will be.

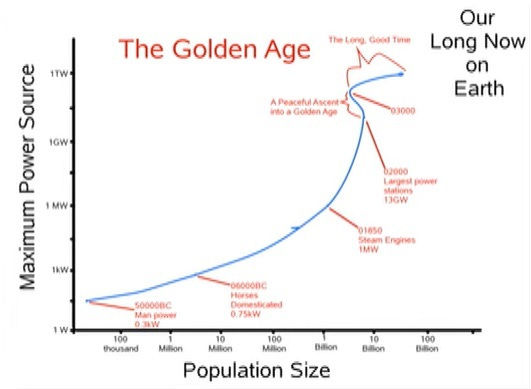

Science fiction writer and futurist Vernor Vinge (who died yesterday from Parkinson’s disease) imagined a scenario — though not a likely one, he added — where humanity never achieves the Technological Singularity of self-improving artificial intelligence, but things work out OK, anyway. In what Vinge termed a “Golden Age,” global population eventually stabilizes at three billion — where it was back in 1960 — and then humanity settles into "the long, good time." Vinge:

This is the sort of world that I think a lot of people would hope for, think that it might happen. It means that somehow we managed to avoid the existential threats that everybody is worrying about. ... And I think there actually are a lot of trends that make that plausible. I see a plasticity in the human psyche that can actually cause large numbers of people to behave in very different ways over short periods of time. I think the leveling off of population growth at the turn of the century here has been an example of that. When you give people hope and information and communication, it's amazing how fast they start behaving with a wisdom that exceeds the elites. And this is something that makes me the most optimistic about the present time, that the governments of the largest countries realize that their national wealth depends more than anything on having large numbers of relatively happy, creative, communicating, educated people. That's where the wealth is. … [Yet] I regard the Golden Age as probably too optimistic because on Earth, there are just dangers and accidents that can happen. It's sort of like having even if everybody are people of goodwill, if they're standing around in a room filled with dynamite of various sorts, it's a dangerous situation. But I actually regard this Golden Age one as it's not an idle or an impossible dream; it would be something that could happen.

Let’s take a step back. Maybe you find falling fertility rates to be alarming. Is population decline such a powerful trend that public policy has, unfortunately, little role to play other than, say, revamping old-age pension and healthcare programs to make them fiscally sustainable in a world with a rising dependency ratio where there are fewer working-age individuals to support the elderly?

Certainly there are policy wonks think we can alter falling fertility rates to some degree, particularly those who blame falling fertility rates in rich countries on what they term “workism.” Here’s the theory:

People in advanced economies like America are too obsessed with work, whether as a means to buy more stuff or as a source of personal meaning and identity.

One result is that more and more of us are choosing a work-life balance with greater emphasis on the former.

This deep desire, by both men and women, to do meaningful and important work — not just have well-paid jobs — has a substantial negative impact on their desire to have children.

The result: declining fertility rates and the phenomenon where people are having fewer kids than they tell pollsters that they want. Bad for our personal happiness today and the health of our society tomorrow.

The last thing policymakers should concern themselves with is ideas that promote a further emphasis on economic production — ideas that would no doubt focus on boosting dynamism (the churn of jobs and companies captured by the idea of “creative destruction”). Dynamism may be great for economic statistics, but less so for families and communities when jobs are lost and companies go out of business or move elsewhere.

If you accept the validity of the workism critique, then you might well have a problem with this newsletter and my book, The Conservative Futurist. They both place great value on economic growth and explore ways to make workers more productive. (For real: A common criticism of my pro-growth, techno-optimist, accelerationist, Up Wing vision is that I ignore its impact on families and family formation. (“My gods, what about the children?”)

While I have written about falling fertility rates, it’s almost entirely been in the context of how having fewer kids will affect future economic growth and tech progress. Briefly: Larger populations have more science researchers, leading to increased innovation and higher living standards. They're more likely to produce brilliant minds like Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein, resulting in more ideas.)

Look, I think it would be great if people had more kids. I have seven kids. Kids are awesome. And lots of people might well be having fewer kids than they might prefer, all else equal. But I also think the best use of this newsletter is in discussing problems that policy might be solved, or at least significantly ameliorated. And I don’t think falling fertility rates are that kind of problem.

Slowing such a powerful and widespread trend, even modestly, would be quite the task for public policy. A significant slowing or a reversal … well, it’s hard to imagine. That, especially with the policies suggested by workism worriers, such as child allowances or encouraging flexible work arrangements. There’s no evidence that such changes would, say, double US fertility rates back to where they were in the early 1960s, from 1.7 percent to 3.4 percent. Nor do these pronatalists claim such impacts are possible, I think. The scale of the challenge just seems like an overwhelming mismatch with the policies being recommended.

But … Imagine a scenario where a significant shift in societal norms and values dramatically transforms our perceptions of family and childbearing. Fernández-Villaverde has highlighted the stark contrast in birth rates between religious and secular groups in contemporary society, a disparity that was virtually nonexistent half a century ago. This observation underscores the profound influence of sociocultural factors on fertility patterns. It is conceivable that, in the future, people's beliefs about family structures and dynamics may undergo a radical transformation. Alternatively, the demographic composition of a society could gradually evolve as a result of religious individuals consistently having larger families over the course of several decades.

Or how about this: What if tech-driven economic growth makes us so much richer that we simply choose to work less? Maybe a lot less. With all that extra time and all those extra resources, maybe we would choose to devote more of both to having more kids. As it is, the rich seems to be having more kids than the poor. What if we all were far wealthier than even the top 1 percent are today?

Imagine if we were to build, through faster economic growth, the sort of future imagined by economist John Maynard Keynes in his famous 1930 essay "Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” As the world was being enveloped by the Great Depression, Keynes attempted to create an upbeat picture of the future to persuade the public that anti-capitalist revolutionaries and reactionaries were wrong. He predicted that by 2030, living standards in Europe and the United States would have advanced so far that the "economic problem" would be solved, and people would want for nothing, except perhaps purpose. While some work would still be needed to order their lives, a few hours a day would suffice. Keynes:

I feel sure that with a little more experience we shall use the new-found bounty of nature quite differently from the way in which the rich use it to-day, and will map out for ourselves a plan of life quite otherwise than theirs. For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!

In the language of modern Wall Street, it was a pretty good top-line macro forecast. Real per capita GDP in the US has risen by 6.4 times, right in the middle of Keynes's forecast. As UCLA economist Lee Ohanian wrote in a 2008 analysis for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis,

Would any economist today, even with the benefit of training in frontier growth theory, try to make serious economic projections 100 years out? Very unlikely, but Keynes did, and did so remarkably well — in all honesty, much too well — given the available theory and the existing economic conditions when he was writing.

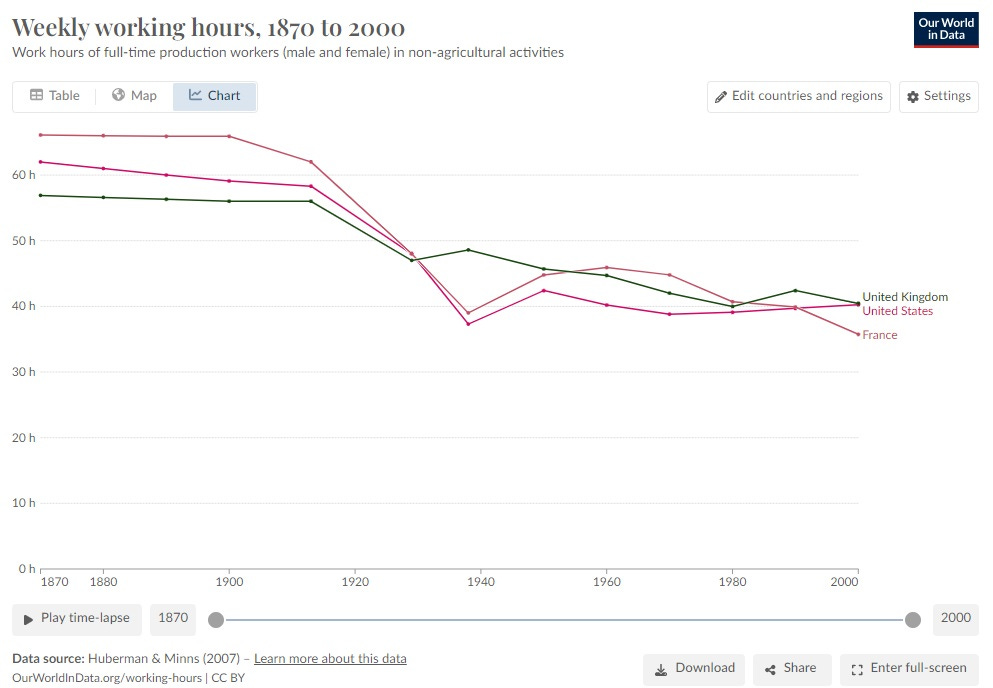

Less impressive is the bit about working just a few hours a day, which was probably meant more as a thought experiment than a serious forecast. “Full-time” workers today aren’t working 15 hours a week — even assuming more than a bit of time is spent doing online shopping or flicking through social media — despite decades of economic growth.

(Why? Lots of marvelous new goods and services to buy, jobs became less physically grueling, and the advent of the notion of “retirement.” The late economist Nicholas Crafts notes that between 1931 and 2011, expected lifetime hours of leisure and non-market work in the UK rose by 60 percent, “considerably more than Keynes would have expected [with] the need to accumulate sufficient savings to support this lifestyle presents a significant obstacle to reducing the workweek to a mere 15 hours. Indeed, workweek declines seem to have stagnated in recent decades as people have chosen to spend increased incomes on consumer goods rather than work less.)

As it happens, the issue of the length of the workweek is in the news. Senator Bernie Sanders has legislation that would reduce the standard workweek from 40 hours to 32 hours. Workers eligible for overtime would get paid extra for exceeding 32 hours in a week. Sanders argues that, thanks to recent advances in AI and robotics, workers have become more productive and thus American companies can provide their employees with increased time off without reducing their pay or benefits.

Sanders is jumping the gun here. Despite a recent upturn in productivity growth, it’s far too soon for Washington to make big economic decisions based on what could be a passing bit of volatility, especially with an economic stat that’s notoriously jumpy. That said, tech progress might well, at some point, reduce the length of the work week if productivity should surge and income growth accelerate, leading to a desire by people to work less and spend more time on leisure — a desire that might also include bigger families with whom to spend Martian vacations. Tech-driven productivity growth seems to me to be the most likely path to a shorter work week and greatly altered work-life balance.

A report from the think-tank Autonomy's report suggests that 8.8 million UK workers, or 28 percent of the workforce, could shift to a 32-hour, four-day week due to AI-driven productivity gains. Additionally, 27.9 million, representing 88 percent of the country’s workforce, could have working hours reduced by at least 10 percent. (Autonomy made its calculations using the 1.5 percent annual productivity increase from AI recently estimated by Goldman Sachs.) Basically, the report forecasts two scenarios: a 20 percent reduction in hours with unchanged pay or a 10 percent productivity increase leading to 10 percent fewer hours, also with unchanged pay.

Along the same lines:

Investment bank Jefferies predicts “A.I. will make workers much more efficient, leading to a broader acceptance of four-day work weeks.”

JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon recently said that he believes AI could lead to 3.5-day workweeks for the next generation.

Microsoft founder Bill Gates is anticipating a three-day work week could be possible thanks to advances in AI.

Want to slow or turn back the seemingly unstoppable trend of falling fertility rates? Tech progress and economic dynamism are your friends, not your enemies.

Micro Reads

Business and Economics

Open-Source Companies Are Sharing Their AI Free. Can They Crack OpenAI’s Dominance? - WSJ

Nvidia’s Rise Surprises Even the Researchers Who Started AI Boom - Bberg

Artificial Intelligence Capital and Employment Prospects - SSRN

How will Language Modelers like ChatGPT Affect Occupations and Industries? - SSRN

This Company Helped Make AI a Reality. Now the Machines Are Crushing It. - WSJ

Perplexity's Founder Was Inspired by Sundar Pichai. Now They’re Competing to Reinvent Search - Wired

Microsoft hires DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman to run new consumer AI unit - FT

Navigating the Future of Work: Perspectives on Automation, AI, and Economic Prosperity - AEI

8 Google Employees Invented Modern AI. Here’s the Inside Story - Wired

Artificial Intelligence and the Discovery of New Ideas: Is an Economic Growth Explosion Imminent? - SSRN

Policy

AI may not change your job, but it will transform government - FT Opinion

In Defense of Pylons, Magnets for NIMBY Ire - Bberg Opinion

The AI Act is done. Here’s what will (and won’t) change - MIT Tech Review

AI

GPT-5 might arrive this summer as a “materially better” update to ChatGPT - Ars

Why AI conspiracy videos are spamming social media - FT Opinion

Google DeepMind unveils AI football tactics coach honed with Liverpool - FT

Saudi Arabia Plans $40 Billion Push Into Artificial Intelligence - NYT

Nvidia Unveils Blackwell, Its Next GPU - IEE

BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance - Arxiv

Health

Has Neuralink made a breakthrough in brain implant technology? - NS

Watch Neuralink’s First Human Subject Demonstrate His Brain-Computer Interface - Wired

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone - MIT Tech Review

Antibodies against anything? AI tool adapted to make them - Ars

‘A landmark moment’: scientists use AI to design antibodies from scratch - Nature

Dog Longevity Startup Loyal Secures $45 Million in Funding - WSJ

Common antibiotics can regenerate heart cells in animals - NS

Clean Energy

If You’re an AI Bull, Keep an Eye on Uranium - Bberg Opinion

Bill Gates’ TerraPower plans to build first US next-generation nuclear plant - FT

Storing Renewable Energy, One Balloon at a Time - NYT

A nuclear plant’s closure was hailed as a green win. Then emissions went up - The Guardian

Western countries ‘too optimistic’ on nuclear projects, warns engineering chief - FT

Robotics

A replacement for traditional motors could enhance next-gen robots - Stanford

Space/Transportation

SpaceX’s workhorse launch pad now has the accoutrements for astronauts - Ars

Life’s building blocks are surprisingly stable in Venus-like condition - MIT

SpaceX’s Shotwell Downplays Potential Starlink IPO - Bberg

Up Wing/Down Wing

Vernor Vinge, father of the tech singularity, has died at age 79 - Ars

Deeply Unhappy Gen Z and Millennials Cause U.S. to Drop in Global Happiness Ranking - Gizmodo

It's not a technology problem. It's the western attitude that human life isn't just worthless, but a negative. Hence the acceptance of abortion and the killing of 17-25% of the children in the womb. Because if born, they'll be a dreadful burden on those women.

As well as, feminism (we're all feminists now) and the mass entry of women into the workforce and making their own money combined with placing them in sole control of reproduction. The vast majority of women want to get together with men they view as higher status ( by looks and/or status and/or resources) they find 80% of men unattractive, and only the top 5% attractive enough to pursue. They don't need a guy to support them, and will continue to only want to have kids with those men. They don't see family as a goal-- only a part of getting into a relationship with the right man.

In the long run I'm imagining people's health spans being longer. As in they have the health of a 30 something uptill their 70s. This might cause people to have two sets of kids. Two when they are in their 30s and another set when they are in their 60s.