🚀 Faster, Please! Week in Review #68

Please check out some great highlights from my essays and interviews!

My free and paid Faster, Please! subscribers: Welcome to Week in Review. No paywall! Thank you all for your support! For my free subscribers, please become a paying subscriber today.

Melior Mundus

I have a new book out. The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is currently available pretty much everywhere. I’m very excited about it! Let’s gooooo! ⏩🆙↗⤴📈

In This Issue

Best of the Pod (+Transcript)

— My chat with Marc Andreessen on the need for techno-optimism

Essay Highlights

— How an economist thinks about the AI dilemma: growth vs. existential risk

— How a New Roaring '20s could be like ... the Booming 1990s. Still.

From the Archive

🌞 My chat with Marc Andreessen on the need for techno-optimism

If you’re looking for a smart and punchy companion piece to my new book, The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, then you are in luck. Look no further than venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s wonderful new mega-essay, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.” If there’s a sentence or even a word in that manifesto that I disagree with, I have yet to find it. That’s why I am so delighted to have Marc Andreessen, a founder and general partner at Andreessen Horowitz — as well as the co-author of Mosaic, the first widely used web browser, and co-founder of Netscape — on this special episode of Faster, Please! — The Podcast. You can also check out the transcript here: My long read Q&A with Marc Andreessen on the importance of techno-optimism.

James Pethokoukis: One selfish thing I really love about the Techno-Optimist Manifesto is that it affirms to me that my new book, The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, which you nicely blurbed, got the big things right — especially that what we believe about technology and our ability to use it wisely and productivity matters.

Indeed, the main thrust of the manifesto — and you can correct me if I have this wrong — is promoting a substantive optimism about technology and economic growth as forces that can improve people's lives and society overall. It advocates embracing innovation, markets, societal ambition and human achievement as ways to create material abundance. But an obvious question: You're busy, you're the co-founder, general partner of a large VC firm. Why is it a good use of your time to write and talk and promote the ideas contained in the manifesto? What is the expected return on investment here?

Marc Andreessen: I alluded to this at the beginning of the manifesto. If you go back in history, to the First, but also particularly the Second Industrial Revolution, the period of 1880 to 1940 when a huge amount of the modern world that we all have today, everything from electricity to cars and telephone and all these things that we take for granted today, that's when those things really happened. If you read the accounts of what it was like in that era, people had a tremendous level of faith and confidence in innovation and in technological creativity, business creation — and there were huge fights along the way. There were huge fights with the “robber barons” and so forth, but by and large, there was this fundamental belief in what you might call “Progress” with a capital “P.” That's captured in a lot of the fiction at the time, but also a lot of the nonfiction, even critics of capitalism were very excited about technological progress at that point.

In fact, a big argument for communism in that era was that you had so much technological progress coming that you could finally make communism work. And I just think that the world we live in today is not that world anymore. It's sort of the post-1960s Baby Boomer world in which there's this suppressive cultural blanket that's kind of been coming down on top of people who have been genuinely trying to create new technologies and create new businesses. There's what I call in the manifesto a “demoralization campaign” where there's just a tremendous number of outside observers or critics — including the press, governments, think tanks, nonprofits, activists, politicians, big company executives who maybe have ulterior motives — there's a huge number of people who are actively trying to demoralize people, trying to build things, and trying to create things. Our founders feel this. It's hard to do something new, and it's even harder when basically people are telling you that you're bad and evil for trying. The way I write is I sort of wait until I reach a boiling point where I just simply can't take it anymore and then I slam my pen into the desk and decide it's time to put it on paper, so that's basically what happened.

Essay Highlights

🤔🤖 How an economist thinks about the AI dilemma: growth vs. existential risk

Amid America’s burgeoning panic — especially among its elites — about the latest advances in artificial intelligence, let’s take a breath: AI, especially large language models such as ChatGPT and other chatbots, presents both opportunities and risks. Can we agree on this? They might greatly boost technological progress and economic growth by enhancing innovation and labor productivity. (Yay!) Yet many people worry that AI could also one day pose a catastrophic threat to humanity if an artificial superintelligence diverges from human values, potentially causing disaster, and even human extinction. (Boo!) Imagine a scenario where AI is developing at a rapid pace and is starting to do the jobs of humans, particularly in creating new ideas and inventions. “Next stop; AGI!” Instead of the US economy growing a few percent a year, it’s now growing at a white-hot 10 percent annually. Yet the more we use this ever-evolving AI, the higher the risk of something going horribly wrong, potentially ending human civilization. On the one hand, you have the potential for spectacular economic growth. On the other hand, there's a chance that everything could end. How do you balance the possible reward and risk?

💥 How a New Roaring '20s could be like ... the Booming 1990s. Still.

For the past couple of years, the bank UBS has been making its own case for a Roaring ‘20s, using the boomy 1990s as the relevant historical analogy. It’s an analysis that the UBS investment team returned to in a new report: “Another Roaring ‘20s for the US: It depends on the supply side.”

The envisioned economic scenario for a Roaring ‘20s:

sustained high GDP growth of 2.5 percent or above (about a half point faster than current expectations);

moderate inflation between 2-3 percent;

a 10-year Treasury yield around 4 percent;

and a federal funds rate between 3-4 percent.

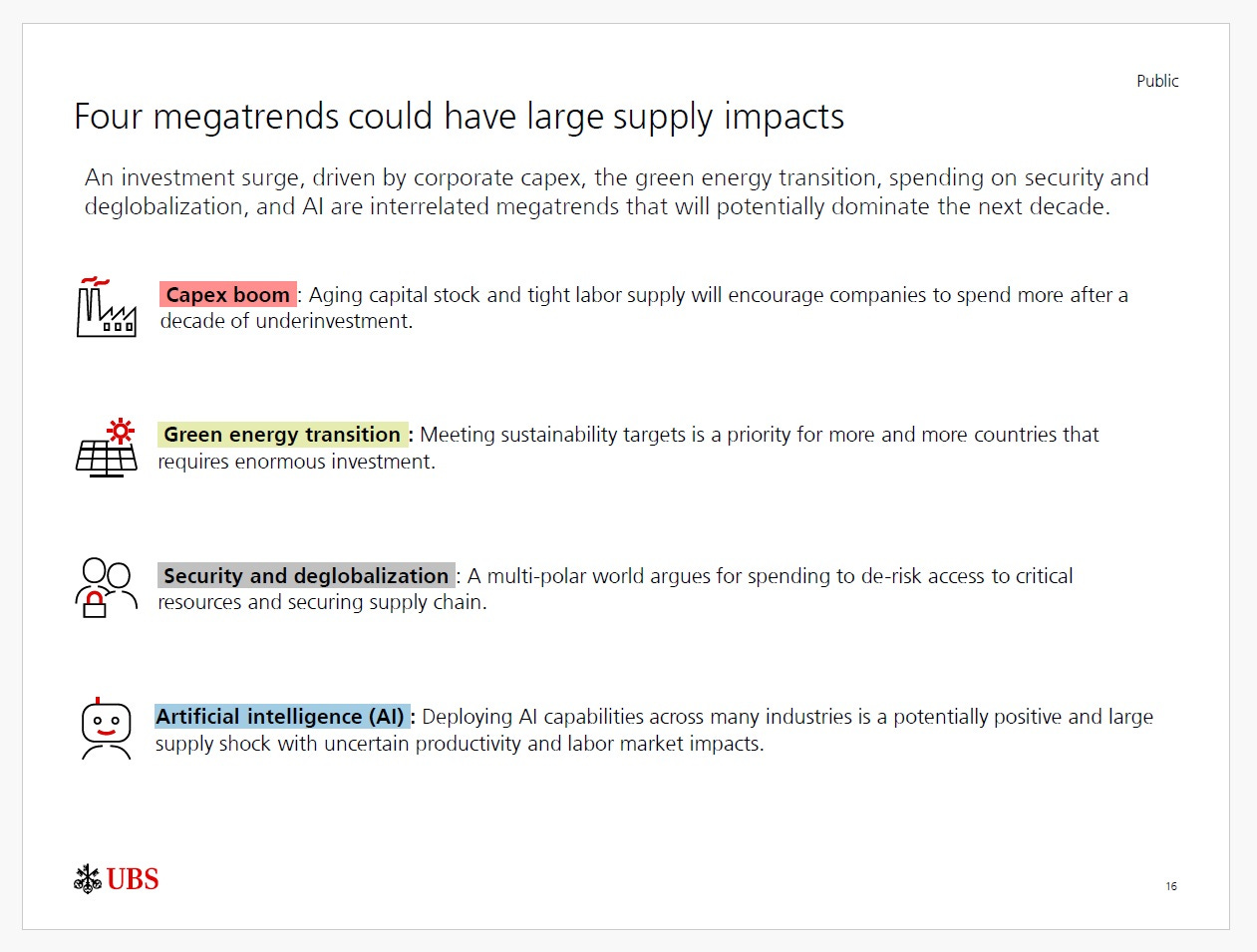

This scenario relies heavily on the supply side of the economy, which UBS sees as currently challenged by issues like labor and housing shortages. (These supply constraints are juxtaposed with solid household finances, expected to support demand this decade, unlike the 2010s.) Four major trends are projected to shape the supply-side dynamics this decade — though not all will be good for productivity growth, an accleration of which sits at the core of the UBS thesis:

a capital expenditure boom driven by prior underinvestment and labor scarcity;

a significant investment in the green energy transition;

changes in security and a move towards deglobalization requiring vast investment;

and … wait for it … the deployment of AI that could act as a positive supply shock.

From the Archinve:

🤖 AI has risks. So does regulating it.

It’s not surprising given the current geopolitical climate that the emergence of large language models such as ChatGPT immediately prompted questions about China’s generative AI capabilities. That, especially as the performance of LLMs quickly led to speculation about their progression to artificial general intelligence. That would mean a communist, authoritarian state was on track to create one of the most powerful technologies ever devised by humanity. The barely contained American panic during World War II about the Nazi Germans getting the atomic bomb first might pale versus the panic today of losing the AI race. As it is, the specter of falling behind China, as suggested by Eric Schmidt, should provide a powerful incentive for policymakers to show great caution in any effort to create a special regulatory regime for AI.