😎 My long read Q&A with Marc Andreessen on the importance of techno-optimism

Here's the edited transcript of my podcast with the venture capitalist

Yesterday, I published my podcast with Marc Andreessen. And as promised, here’s the lightly edited transcript of our conversation. (All errors are mine. If something reads strangely, feel free to check the audio.)

If you’re looking for a smart and punchy companion piece to my new book, The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, then you are in luck. Look no further than venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s wonderful new mega-essay, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.”

If there’s a sentence or even a word in that manifesto that I disagree with, I have yet to find it. That’s why I am so delighted to have Marc Andreessen, a founder and general partner at Andreessen Horowitz — as well as the co-author of Mosaic, the first widely used web browser, and co-founder of Netscape.

James Pethokoukis: One selfish thing I really love about the Techno-Optimist Manifesto is that it affirms to me that my new book, The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, which you nicely blurbed, got the big things right — especially that what we believe about technology and our ability to use it wisely and productivity matters.

Indeed, the main thrust of the manifesto — and you can correct me if I have this wrong — is promoting a substantive optimism about technology and economic growth as forces that can improve people's lives and society overall. It advocates embracing innovation, markets, societal ambition and human achievement as ways to create material abundance. But an obvious question: You're busy, you're the co-founder, general partner of a large VC firm. Why is it a good use of your time to write and talk and promote the ideas contained in the manifesto? What is the expected return on investment here?

Marc Andreessen: I alluded to this at the beginning of the manifesto. If you go back in history, to the First, but also particularly the Second Industrial Revolution, the period of 1880 to 1940 when a huge amount of the modern world that we all have today, everything from electricity to cars and telephone and all these things that we take for granted today, that's when those things really happened. If you read the accounts of what it was like in that era, people had a tremendous level of faith and confidence in innovation and in technological creativity, business creation — and there were huge fights along the way. There were huge fights with the “robber barons” and so forth, but by and large, there was this fundamental belief in what you might call “Progress” with a capital “P.” That's captured in a lot of the fiction at the time, but also a lot of the nonfiction, even critics of capitalism were very excited about technological progress at that point.

In fact, a big argument for communism in that era was that you had so much technological progress coming that you could finally make communism work. And I just think that the world we live in today is not that world anymore. It's sort of the post-1960s Baby Boomer world in which there's this suppressive cultural blanket that's kind of been coming down on top of people who have been genuinely trying to create new technologies and create new businesses. There's what I call in the manifesto a “demoralization campaign” where there's just a tremendous number of outside observers or critics — including the press, governments, think tanks, nonprofits, activists, politicians, big company executives who maybe have ulterior motives — there's a huge number of people who are actively trying to demoralize people, trying to build things, and trying to create things. Our founders feel this. It's hard to do something new, and it's even harder when basically people are telling you that you're bad and evil for trying. The way I write is I sort of wait until I reach a boiling point where I just simply can't take it anymore and then I slam my pen into the desk and decide it's time to put it on paper, so that's basically what happened.

Because my book and your manifesto really hit many of the same themes, the fortunate part of that is that I can just sort of ask you all the questions that I've gotten asked — especially the more hostile ones — and this is one I've gotten by people who just don't agree with the thrust of the argument, they'll say, “What do you mean there's not techno-optimism? I thought we were the techno-optimist country. We love smartphones, we look for technology for answers. I mean, we have Silicon Valley. I mean, how can you say we're not a techno-optimist country?”

I think there's a lot of truth to that, and this is something that we talk a lot about inside the tech industry. One, it's always important to try to figure out what people think. It's always important to disambiguate between the things that they say and the things that they do. And so it's polls and surveys on the one hand, and then what social scientists call “revealed preference” on the other hand, which is actual behavior. It's always important to disambiguate both of those. If you look at revealed preference, you alluded to this, the real preference: People love this stuff, right? This is the ultimate irony of all the critics of tech is that they're all tapping away on their iPhones, posting on Twitter, going on YouTube. And so revealed preferences is people love this stuff. We live in a world today in which more people in the world have smartphones now and broadband mobile access than have access to electricity and running water. There's a big revealed preference thing where people love this stuff.

Then even in the polling, it's very interesting if you do mass polling — and both Gallup and Edelman do this for trust in institutions over time — actually big business and big tech actually polls very high, and I think it's in the Edelman trust survey where big tech actually polls the highest of all the sectors of business, and of course big business out-polls almost every other kind of institution. I remember Edelman, the guy who runs it kind of came and said, “You guys had a huge crisis a few years back when people started to criticize tech.” I looked at the numbers, and it was like trust in Big Tech had fallen from 72 to 70 or something. Just imagine how excited Congress would be if they were polling at 70 percent, because they poll at like 15 percent.

The way I would describe it is there's sort of a separation, as there often is, in these kind of cultural, political, societal things. There's a separation between the people, or the masses, where by and large people are actually quite optimistic and quite happy, and then the elites, and of course what my manifesto was very much aimed at — I mean everybody's obviously free to read it — but the critique that I specifically make is of our elite culture, not our mass culture. The good news is that it's not our mass culture. The bad news is the elites really matter, right? Because the elites are the people who set policy. The elites are the people who decide what's in the media. The elites decide what shows up in our fiction, in our aesthetics. The elites are in a position to get people fired. The elites are in a position to cause progress to stop.

The SpaceX Starship rocket — which is one of the most important new innovations in our civilization in the last 50 years, offers for the first time the potential for infinitely reusable travel to and from space — that thing is currently held up on the launchpad for what looks like might be months because elite bureaucrats have decided that it threatens some particular kind of bird. There was no vote that we're going to make that tradeoff, but there's a bureaucratic class in this country that is very anti-tech and very anti-change, and they're holding up that, and they're attempting to hamstring many other areas of technology right now. So I think it's important to address them directly and talk about them directly.

There was a definite downshift [in innovation ] … And the way I think about this is that the sectors in which innovation has been allowed to happen have leapt ahead.

Why has there been a downshift in innovation?

Progress has been made, I mean we'll call the period since 1970, they call it the “Great Stagnation,” in my book I call it the “Great Downshift,” but I would rather live today than in 1990 or 1980, 1970. So what was lost? What does the world look like if we had a never-ending ’60s or a never-ending late ’90s? What does that gap between where we are and where we could be if we had a more optimistic culture — that and policy both supporting each other.

The framing here is that sort of classic Bastiat concept of the seen and the unseen, and so we do see the progress that has happened, and of course there has been progress. Obviously the internet and computers have had a lot of progress in that time period. Then, of course, this goes to the conversation about risk and why things slowed, but we see risks and then what we don't see — exactly to your question — we don't see the things that have been lost. You have to decide with these questions of whether you care about those things or not. My view is that the things that are lost that you don't see are every bit as important as everything that you see, because it’s opportunity cost, which is a form of cost. It's real. It really affects people's lives. So, yes, this scorecard sense in the last 50 years is, I think, pretty clear.

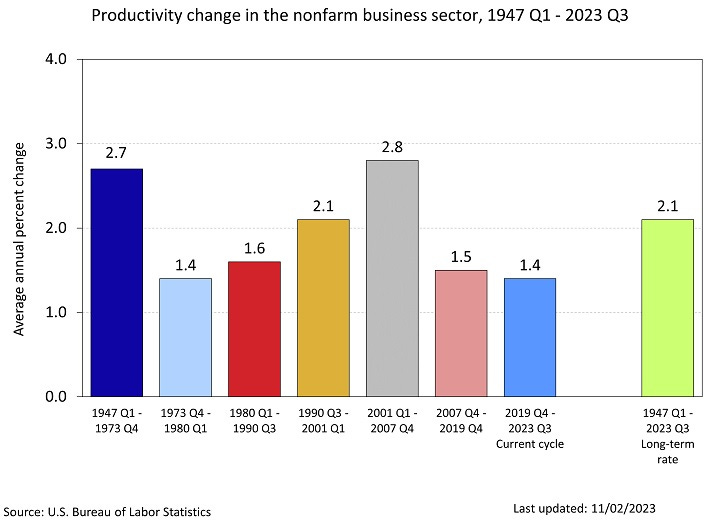

So one is just statistically, numerically, productivity growth downshifted in the economy. In the Second Industrial Revolution and then all the way post-World War II through the 1960s it was growing at a significantly higher rate, something like double the rate of productivity growth in the economy versus since 1968 or so. There was a definite downshift. You disambiguate that obviously by sector and basically what you see, the way I think about this is what you see is the sectors in which innovation has been allowed to happen have leapt ahead.

The two things that have happened in those sectors is very rapid productivity growth because of innovation, and then the other is very rapidly falling costs, which then ripples through to prices for consumer goods. If a good falls in price as a consequence of technological change, that's the equivalent of everybody getting a raise. That's a rise in real incomes. There are sectors of the economy like tech and your television set on your wall and your streaming media and so forth where that has taken place.

Against that, you have other sectors that are much larger and extremely foundational to quality of life, sectors like healthcare, education, housing — by the way, government, I would say is an economic sector, and everything's sort of attached to it — and those sectors have experienced profound technological stagnation to the point where, I don't know whether this has been measured, but I think they're probably going backwards. They're probably experiencing reduced productivity over time due to administrative bloat, just like enormous numbers of people doing email jobs.

Then, of course, the result of that is far higher prices. This is where you get these incredible paradoxes of where things sit today where a four-year college degree for your kid is on its way to a million dollars and a 100-inch TV that covers your entire wall and looks spectacular that you can watch Netflix on all day long is on its way to a hundred dollars. Is that really the optimal distribution of innovation? Is that really the world that we want to live in? If current trends continue, that's exactly what we're on track for.

People have pointed out to me, they're like, “Well, we've had this information technology revolution.” Are you suggesting that we wouldn't have had it under a different sort of policy regime, whether it's different regulations, different government spending on R&D? Everything you read about now, whether it's possible breakthroughs with fusion or generative AI, and there was just this huge CRISPR advance where we might've found a cure for sickle cell disease. What has been lost by not having those advances in 1995 instead of 2023?

Yeah, for sure. I mean, Charles Babbage almost got the computer to work in whatever it was, the 1870s or something. There was actually this artificial intelligence kind of thing that is happening now. There was a big debate in the 1930s as to whether computers should be modeled after calculating machines, in which case they would be sort of hyper-literal and do math really fast or whether they should be modeled after the human brain. The first neural network paper was actually written in 1943. The architecture of Chat GPT is basically based on that paper from 1943. These ideas pop surprisingly early, and so it is a question of how fast do you get the payoff? Then, of course, it's a question about what have you lost, what have you not achieved?

One lens I would put on this that I didn't mention in the essay, but I think is relevant to your question, is the innovations in the Second Industrial Revolution, the car and the railroad and electricity and nuclear power, these were things that were big. The spaceships, airplanes, the Concorde, the Hoover Dam, these were things that were large, these are things that had physical force and presence in the world. Richard Feynman, who was of course in the Oppenheimer movie, was one of the key guys in physics in the 20th century. He said this thing around the turning point where people started to really shift their thinking on innovation, he had a famous talk where he said, “There's lots of room at the bottom.” What he meant is that there's actually a lot of innovation that can take place by making things smaller, and splitting the atom was an early example of that. It turns out, of course, in the computer revolution, that's been the key to the whole thing, which is Moore's law. Basically, shrinking transistors to the point now where they're at whatever, two nanometers, and then you can pack billions of them or trillions of them on chips.

What's happened is Feynman was right. There's plenty of room at the bottom. Innovation has taken place in microchips, in fiber optics, in software, in algorithms, in data. It's either so small you can't see it or it's immaterial. I think we got this 40- or 50-year run where a lot of people weren't threatened by it because it is easy to get threatened by a massive airplane or a big dam or something. It's much harder to get threatened by a microchip. We sort of got a free pass for innovation in microchips and software because they were, in some sense, either tiny or immaterial. The alarming thing I would say that's happening right now is the same kind of fearmongering that took place around atomic power and took place on many of the other technologies that have really slowed down or stopped in the last 50 years — that same kind of fearmongering and emotional hysteria, anti-tech hysteria is now being applied into computers and into software.

The advances in medicine that are not taking place today because we are trying to hold back AI. According to the principle — the seen and the unseen — those preventable deaths are every bit as severe and important as actually people picking up a gun and shooting somebody.

The importance of embracing AI

To me, it's sort of stunning that we're sitting here, we have these debates about climate change where it's obvious that if we had coast-to-coast nuclear reactors, maybe small ones, maybe fusion reactors, we would be having a very different debate, and yet, in some cases, the exact same people who are against nuclear are now also saying, “We need to pause AI, we need to heavily regulate it.” To me, one of the bits of the essay that really pops out is when you suggest that slowing down AI is really tantamount to causing preventable deaths. It's a line that has bugged some people, they think it's an extreme line. To me, it's an obvious truth, but defend that, defend that line as a way of making your case for accelerated AI, not squashed AI.

If you want to talk about atomic power, Richard Nixon did two things relevant to energy in the early ’70s that really mattered in the history of this. One is he declared something called Project Independence where he said, “We need to build a thousand new nuclear power plants in the US, domestic plants, by 1980. We need to become completely energy independent, we need to go completely electric.” So that would've been accompanied by a shift to electric cars. Electric cars are a hundred-year-old technology, it's a great example of something you're talking about that we could have had a lot sooner. He said, look, we need to get self-sufficient, and then not only are there environmental benefits to this, but there's geopolitical benefits, this is what will get us disentangled from the Middle East and then we won't need to be sending our kids over there anymore in these wars.

So on the one hand, he said that, and on the other hand, he created the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which then prevented that from happening. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission didn't approve a new nuclear power plant for 40 years. If you're on the left, you could basically say, “Yeah, everything that happened in carbon emissions in the developed world over the last 50 years was completely preventable. We could have a zero-carbon electric grid today with at least as much, or more, power than we have, and we chose not to do that and we're still continuing not to do that, but you don't even need to get into climate change to kind of justify that on a morality basis.

You just look globally, you look at energy production, and you probably know the answer to this: what's the number one cause of energy-production environmental death worldwide? It's people burning biomass in their own homes. Millions of people die every year because they’re burning wood or some form of biomass inside their own homes and they're getting poisoning from the smoke and they and their kids are dying. There's mass death happening all over the world as we speak by virtue of the fact that we have not rolled out modern energy everywhere. At just an absolutely staggering level. Now, of course, that's hard to see because we're not sitting in the village watching somebody die in their hut because they’re burning wood, but nevertheless, it is real. In a very similar way, the advances in medicine that are not taking place today because we are trying to hold back AI. According to the principle — the seen and the unseen — those preventable deaths are every bit as severe and important as actually people picking up a gun and shooting somebody.

When I say that it's the same arguments, and in some cases it's the same people and organizations, what I find stunning, really, I guess not surprising, is that not only are some people worried that AI will increase inequality, cause job loss, it will kill us, but they're saying, “You know what? Even if you think it's good, it just uses too much energy. We cannot afford to have AI everywhere ubiquitous that everyone will have access like they do a smartphone.” It’s the exact same argument that we are running out of everything, we are running out of energy, and thus we need to stop, we need to retreat. I'm wondering if you think that these arguments will have traction going forward as they apparently have had for a half-century?

I would even argue this goes back 100, 120, 140 years. I think you can trace this mentality back to communism. I think you could trace it back to Fabianism. It's this elite-driven thing that basically, at the heart of it, is that civilizational progress as we have understood it is fundamentally evil, and you can sort of hang whatever instance you want on that. Lots of foreign policy issues get hung up on this, about how evil American involvement is in various issues around the world. There's lots of economic claims on the evils of capitalism, despite obvious proof over the last 150 years that capitalism is the engine to bring people out of poverty. You still hear the opposite.

When it comes down to it, I kind of turn to Thomas Sowell and his great book on this topic, which is A Conflict of Visions. He wraps the whole thing up in a way that made it easy for me to understand, which is that there's fundamentally two visions for how the world plays out, for how society should be ordered in the modern world. One is the “constrained vision” in which humans are fallible, imperfect, and flawed, and we try to be practical and we try to make change in the margin that makes things somewhat better. And then there's this sort of utopia, what he calls the “unconstrained vision,” which is this theory of a fundamentally revolutionized world in which everything will be fair and free and equal and wonderful, post “the revolution,” capitalism will be gone and technology will be purely wielded by the selfless state on behalf of the people, and you won't have any more war because you will have a global government, you’ll have global authorities in charge of everything. That's been the battle of capitalism versus socialism over time. That's been the battle of authoritarianism versus proper, capital “L” Liberalism. That's been the battle of tech stagnation versus innovation every step of the way. I broaden it out to that level because what you're saying I think is right, which is basically, it is amazing how these ideas line up. It's amazing how it is amazing how predictive it is. If I know your opinion on nuclear power, I basically know all of your other political views.

You really don't need to poll: “Are people tech-optimistic? Are they future-optimistic?” You really just have to ask them, “What do you think about nuclear power?” and you're about 90 percent of the way there.

By the way, on issues that have nothing to do with technology, you're 90 percent of the way there. You can predict their views on Israel and Palestine from that with almost complete, perfect certainty.

Social Security reform, you're all the way there.

It's a conflict of visions. It's a very deep and profound and powerful conflict of visions, and for that reason, these questions need to be engaged with seriously and at depth because these aren't about the individual technologies. There's a deeper question of the ordering of society.

We're not perfect. We are deeply flawed. … Humanity, but more specifically, technologists, we're deeply flawed also — and the technologies we build are deeply flawed

Slouching towards Utopia: Marc’s response to AI critics

One criticism is that it’s just the opposite of what you're saying right here. You’re the one with the unconstrained vision, you're the one outlying this sort of techno-utopia, that if only there are no regulations and people like yourself are the driving force in society at all levels, that we will create this utopia of everyone will be living to 300 and we'll have mastered the solar system and there'll be no tears, there'll be no suffering. If only we have unconstrained techno-capitalism. You have the unconstrained vision. How do you respond to that?

I use this wonderful term from the economist, Brad DeLong, who I don't agree with on everything, but I think he got this term exactly right. He uses the term “slouching towards utopia.” His description of capitalism is sort of “slouching towards utopia.” What does that mean? It's like, yes, there is some vision out there of a better world. In my case, it’s not a vision of a perfect world, but a better world. But then I love this term slouching, which of course is from the Slouching Towards Bethlehem kind of thing, but slouching towards utopia, which is like, we're not perfect. We are deeply flawed. By “we” I mean every one of us as human beings. Humanity, but more specifically, technologists. We're deeply flawed also, and the technologies we build are deeply flawed.

This is part of the difference. We do not live in the world where we get capital “U” Utopia. We do not live in the world where we get perfection. We do not live in the world where we get people with perfect motives. We do not live in a world in which a single global government is going to make all decisions in a wise and kind way. We just don't live in that world. We live in a world of imperfection where we can slouch towards utopia by making small changes on the margin.

The other great term on this is Tyler Cowen's term, right? “Marginal revolution,” which is the title of his blog. It's the same concept: revolution on the margin. We may have big long-term goals, but actual effective change happens on the margin. Why does that make sense? Because somebody's got to, at some point, sit down and write computer code. Somebody's got to sit down with the slide rule and design the Apollo rocket. Some fallible human being is doing this, so of course there's going to be fallibility throughout the entire process but, nevertheless, these are the things that we can do.

On AI in particular, it seems that most of the focus has been on fallible technologists and the potential risks from this technology, so what would you want policymakers to understand about the potential and risk about AI?

All new technologies bring risks. This is part of not being utopian, right? All new technologies bring risks. I would start with fire. The opportunity and risk of the harnessing of fire is so deeply encoded into our civilizational memory that the Greeks had the myth of Prometheus. The myth of Prometheus was that Prometheus is sort of a God who brings mankind fire and, in revenge, the bigger God, Zeus, chains him to the rock and has his liver pecked out by bird every night, and then it regenerates so he can be tortured again the next day. And if you think about what's encoded into that myth, it’s basically the same argument we're having around AI, which is fire is wonderful; it can keep us warm, it can keep us safe, the first thing that you do if you're in the woods is you build a fire, it's how you keep the wolves away, it's how you cook food, you can use it as a method of defense, but fire also gets used as a weapon and it got used as a weapon when it was literally just people with wooden sticks, and it gets used as a weapon today in the form of munitions and atomic bombs.

Technologies are double-edged swords. There's just two very different ways of going about processing that basic fact. One is the mentality that we had again during the Second Industrial Revolution up until probably 1960, which was that we're going to harness the good and we're going to deal with the bad, but we're going to move forward. We're not going to cower in fear. We're not going to renounce fire and sit in the dark and the cold because we're worried about how bad guys might use it. Technology is a tool. We are in charge of the tool. We are going to step up and figure out how to use it for the good things and how to mitigate the risks.

Since the 1960s, 1970s, the world of policy around this has gotten increasingly consumed by this idea called the “precautionary principle.” Either people actually literally cite this or they behave like it, even if they haven't heard of that term, which is this idea that new technology should not be allowed to exist unless they're proven to be harmless.

Better safe than sorry.

Better safe than sorry. And of course what that is is universal solvent to prevent all new technology. You can always make the harm argument. This to me is a very big reason why productivity slowed down. This is a very big reason why prices in so many areas of the economy are exploding. It's becoming harder to have a middle-class life. This is why we don't have an all-electric nuclear power grid today, and it's that same mentality that's being applied to AI. It's every bit as big a mistake for AI as it was for anything else.

What is the upside? I mean, I realize the essay is not just about AI, it's about technology more broadly, but is this technology, generative AI in particular and these large language models, will it be as important as the PC-internet combo, would it be something greater? What really might be lost if we screw up the regulation of this technology?

It's the introduction of machine intelligence. The analogies here are a little bit dangerous because the machine neural network is not the same as the brain neural network, the human and so forth, and there are big differences here, but there is this universal idea of intelligence — intelligence in humans and intelligence in terms of AI, basically what it means is the ability to solve problems. It means the ability to sift through large amounts of information and do the kind of composite synthesis that you do when you're trying to figure out how to solve a problem, whether it's a small problem like how to schedule your day, or whether it's a big problem like how to develop infinite electric power — problem solving. Human beings have, in general, done very well over thousands of years by being quite good at solving problems when we really apply ourselves to that, but we are fundamentally limited by our own intrinsic capability, our own intrinsic levels of intelligence.

The opportunity here is basically a step-function upgrade in human intelligence by basically joining the human and the machine in a symbiotic relationship. The opportunity is to take every drug developer and every creative artist of any kind, anybody trying to think through any kind of problem, and giving them a new kind of tool that they can work with that gives them a much greater chance of solving the problem or gives them the ability to solve problems we haven't even thought of yet. So this is potentially the big one. This is the big one that could basically drive everything else in the years and decades ahead.

Marc, I've been waiting. Our whole lives have been spent during the Great Stagnation, the Great Downshift. I have been waiting for this technology to accelerate everything broadly throughout the entire economy and I was allowed to get excited about this for 15 minutes last November, and then I was told, “Listen, it's going to take all the jobs and after it's done taking the jobs, it's going to kill us all,” and that has been sort of the crux of the debate, just how dangerous this technology is, and it's enormously demoralizing.

Yeah, it is. Although, like I said, this is reflective of a deeper worldview. Some people who are anti-AI are spreading the kind of anti-AI hysteria now, some of them are actually true believers in the deep worldview. Like we said, you could predict their views on many other areas of topics of politics in society and be properly horrified. There are other people who just are getting caught up in it because it’s the trendy thing of the moment and they're just kind of saying what they think the smart people are saying. I think it's important to get this stuff on the table. I think it's important to lay this stuff out. It's important to actually get the arguments. It's important to hear from the people who are making especially the most inflammatory claims. It's important to actually explain what this technology is. It's important to actually give people who haven't thought hard about this the information that they need to be able to reason this through themselves. So, yeah, I'd rather not go through this, but I will say, for every person who's demoralized right now, there's somebody else who's becoming radicalized because they're like, “Oh, I see what's going on here. They're not actually like this, that, and the other thing. What they're actually doing is trying to get special advantage for their company or what they're actually trying to do is to push some other political angle, or boy, this person actually just seems like emotionally dysregulated. These people seem like hysterics. Maybe these are not the people we should be listening to.”

Do you find, at least with people who are in the industry who have been talking about these existential risks, that it's more a case of them trying to create a regulatory capture situation or a regulatory environment that they can navigate, but smaller companies or companies yet to be born can't navigate and they're going to cement their incumbency? Is it that, is it a true concern that these technologies will get out of control? Is a little bit of both? I mean, what's your sense of it?

There's this great framework in economics called the Baptists and the Bootleggers. It’s this idea that when you get basically one of these sort of risks — call it risks or prosecutions or whatever, people coming at something and try to ban it or make it illegal or control it like this in the regulatory sphere through fear-driven political action — basically what you find routinely over time as a coalition of what they call “Baptists and bootleggers.” The Baptists and bootleggers were the two blocs that were in favor of alcohol prohibition a hundred years ago. The Baptists were the true believers that really believed that alcohol was evil and was destroying society, and the bootleggers were the people who stood to make a fortune if the alcohol was made illegal because then they could smuggle it in and they'd be the only supplier. And, in fact, what happened was prohibition actually worked. Prohibition created what we consider to be modern organized crime in the US because it gave this huge economic gift to the bootleggers. Basically, you see this pattern over and over again if you read the Wikipedia page for Baptist and bootleggers they give you 30 different examples of this over time.

Well now we have 31.

Now we have 31. So that's what's happening in AI, which is you have a set of Baptists, you have a set of people who I'm positive or true believers, they really believe what they're saying. These tend to be writers and science-fiction-oriented people, and they paint these very vivid pictures of doom and death and all these things. Then you've got the bootleggers. The bootleggers in this case, of course, are not people who are going to make bootleg AI; rather here it's sort of just a straight grab for regulatory capture. It's sort of a straight grab to have these governments basically establish a set of regulations similar to what Dodd-Frank did in the banking industry where there can only be two or three or four companies total that are going to be able to scale the regulatory wall, and then everybody else gets frozen out, and then those companies have a permanent cartel.

This is a pattern that has repeated over and over and over again in our economy. Many, many sectors in our economy have been through that. You know them because you see the cartels. Anytime there's two or three or four companies that have a total lock and there's no startup innovation, one hundred percent of the time there's a regulatory barrier. So what's happening is the Baptists are being used by the bootleggers, so the people who are legitimately afraid are being used basically as a front by a small set of big companies and CEOs who are going for the regulatory capture. I think this is obvious. It's playing out today. It's playing out at this quote-unquote “UK AI Safety Summit”. It is playing out in plain sight. Nobody's even really hiding, they're just kind of doing it. My hope is, by describing it, more people will become aware of what's happening.

The problem with economics is that it's many of the most important ideas in economics — which are very clearly true for people who have looked at them in detail, for which we have 300 or 500 years of evidence to support them — they're counterintuitive.

The economics of techno-optimism

One criticism of the manifesto, and as one critical article put it, it's a “hodgepodge of bad libertarian economics,” and particularly the section that inspired that attack is when you wrote, and I quote, “Productivity growth powered by technology is the main driver of economic growth, wage growth, and the creation of new industries and new jobs as people in capital are continuously free to do more important, valuable things than in the past.”

Now what this writer referred to as “libertarian economics,” that passage you could find in any college textbook describing the fundamental mechanism by which poor countries stop being poor. And I'm wondering if a lot of the criticisms are by a media that just doesn't know very much about economics and probably knows even less about how business works.

I'll plead guilty to hodgepodge, but not to the rest of the criticism. There's a couple of things going on here. So one is that some people have observed that a lot of what I wrote actually would've been — the Clinton-Gore Democrats in the 1990s would've been fine with it. It was not that long ago when basically, this is sort of the feeling that I had when I was writing it, which is, “wow, I am saying things that are radical today and were totally conventional and normie 30 years ago,” which I think just says a lot about the shifts in the culture over the last 30 years. As you well know, understanding economics is both critical but very difficult.

The problem with economics is that it's many of the most important ideas in economics — which are very clearly true for people who have looked at them in detail, for which we have 300 or 500 years of evidence to support them — they're counterintuitive. And you could start there with Adam Smith's idea that you are basically exploiting self-interest in order to get people to do pro-social things in a capitalist economy, comparative advantage, one of the things I do with people when they start bringing up economics is I ask them to define the difference between competitive advantage and comparative advantage. That's really important and almost nobody can explain the difference. Another is basically I ask them to explain what sets wages in the economy, and what I get back is almost always a Marxist argument of it's basically whatever —

Worker voice?

Yeah, right! The conventional answer is basically it's whatever workers can pry away from the evil capitalists. I walk through the idea of setting wages by marginal productivity and then the fact that an employee who's getting underpaid in a free market goes and gets hired up to his level of marginal productivity by another employer. And actually, I don't know, it's almost like a little religious experience when people actually wrap their head around how this works, they actually can come out the other side being like, “Oh my God.” And then the very second thought is, “Why did anybody tell me this before?” And so I kind of think this is one of those things where it's always going to be an uphill struggle like this.

Bryan Kaplan once did this thing where he kind of bent my brain. He said he looked at all the political polling on the mass political views on economic topics, and he said, basically, they're sort of disastrous. He says the median American is no Nazi, but he is both nationalist and socialist. And so what Brian says is, actually, it's a miracle that we live in as free market a system as we do, given how bad people's intuitions are on these economic topics. And people need to decide whether they want to learn these things or not, and if they do, I think we should try to explain it to them and if not, we’ll have to figure out how to deal with them, anyway.

One critique that I found super frustrating was Ezra Klein's column about the manifesto, and in that column — it's a column where he called you sort of a “reactionary futurist,” but he referred to everything that you've been talking about, this change in attitude, policies, government making policies that seem to just not even care about the impact on innovation and growth. He kind of hand-waved it away as an overcorrection and then wanted to move forward. I sense there's just a lack of serious contemplation about what went wrong, and I find it hard to believe that we can move forward if we're just going to dismiss all these errors to pass as a slight detour, because to me we're already seeing them repeated with AI, and how do we move forward if we're refusing to acknowledge what went wrong. What are the next steps forwards? What's next?

I always enjoy Ezra's work, because he’s so smart, and I sort of think of him as the Zeno’s paradox of thinkers like this. He's always getting that much closer to the truth. He's almost there, right? He's so close, but he never quite gets over the hump.

That's what’s frustrating. I feel like, well, he's somebody… he's center-left, I'm on the right, but I could work with him on, like, nuclear energy, on housing density, and then I read that column and I think, maybe I can work with him but I'm not sure he wants to work with me.

He's so close. So the piece that he wrote that I actually recommend to a lot of people — I actually hand this out as much as I can — he wrote this amazing piece about the CHIPS Act about a year ago. It’s this industrial policy program by the government, how to fund new chip plants in the US, and the title of the piece is spectacular: The Problem with Everything-Bagel Liberalism. The piece writes like something I would've written if I had had the time and energy and talent to do the work that he did on it, where he basically goes through all of the policies and restrictions and rules and regulations and prohibitions that are being hung on building these new chip plants. And so it's not enough to say we are going to build new chip plants in the US, it's not enough to say the government's going to pay for them, but the workforces all have to have the perfect diversity balance of the chemical engineers involved, whatever bird nests nearby need to be very carefully taken care of, everything needs to be unionized. Basically, he's criticizing his own side on this.

It’s funny, he interviews the commerce secretary, and he basically hangs her up in the interview on this stuff and kind of gets her on the record and basically says, look, we being sort of liberal progressive Democrats who want these chip companies and chip factories to get built in the US and we want industrial policy to work, we have to not attach every other part of our social-political agenda to these things or the entire thing will grind to a halt, which is of course exactly what's happening. If you look at what's happening with the CHIPS Act, that's precisely what's happening. Of course those plants aren’t getting built. Of course it's impossible to do chip plants in the US. You'll never get approval. They'll never get through environmental review. He's one hundred percent correct. I find him so fascinating. He gets it. He totally gets it right. And then a week passes and he's like, yes, but no, it's the capitalists, it's the greedy capitalists that are the bad guys!

He momentarily forgot that market capitalism is problematic.

Exactly, and then he spends the next six months atoning for it. He's interesting, he’s a very talented guy. He's the fun one to read on that. Most of his peers will not get anywhere near the line. He'll walk right up the line and you could see his tippy toes edging right towards the line, and then he'll just be like, “Ah, nope, can't do it.”

I don't need to get to every kid graduating a university. I don't need to get to even every entrepreneur, but if there's another dozen Elon Musks out there somewhere in the next decade and I get to them, then the whole thing is worth it.

The future of technology policy

Why do you think writing this manifesto will not prove to have been an utter waste of your time? Looking back a decade from now, if there's no need for a manifesto 2.0, what probably went right? And if there is a need for such a document, what probably went wrong?

I think two things. One is using this philosophy as sort of slouching towards utopia or change happening on the margin. A big part of this for us, and for me, was the individual entrepreneur is the target for this, so I always envision the 22-year-old wrapping up their whatever degree and they're thinking about, “What do I do? Do I go work for the government? Do I go work for a big company? Do I start something, get my friends together, rent a garage and try to start the next Google or the next Tesla?” A big part of this is just reaching out to that next generation and giving them… You know, part of it is the intellectual arguments, but I really kind of amped up the feeling on this one to basically give people a sense of energy and ethics and, frankly, morality and emotion that this direction is a really good one.

I don't need to get to every kid graduating a university, I don't need to get to even every entrepreneur, but if there's another dozen Elon Musks out there somewhere in the next decade and I get to them, then the whole thing is worth it. And then there are people in policy circles who are thinking hard about these things, and I've gotten a bunch of positive feedback. I actually tried hard in the thing to make it bi-partisan, I tried to not make it overtly right-wing, I tried to make it kind of even-handed, and we could talk about that, but I've gotten positive feedback from a bunch of Democrats. You can read this as sort of Clinton-Gore economic policy if you want to. It kind of hearkens back to a position that the Democratic Party in the past had been pretty reasonably comfortable with, and there are still Democrats running around who believe that. And then, quite frankly, people on the right maybe tend to be a little bit more pro-free market, although not always, but there’s a lot of distrust and fear towards tech and the tech industry right now on the right in Washington for different reasons. So also articulating a positive vision where people on the right can say, “Oh, these tech people are actually trying to do good things,” I think on the margin that probably helps.

Just briefly, what do you think are the strongest tailwinds that make you confident that we're not going to have another 50 years of not achieving what we could? What gives you that confidence? Is it that we're worried about China? What are the tailwinds out there?

Well, we probably will have another 50 years.

Keep the expectations low, and then we'll easily exceed them, right.

Further proof that I’m not a utopian.

What gives you at least mild confidence that maybe we'll squeak through and do it?

A bunch of things. The last 50 years, the political environment in the US has been dominated by Boomers, just a statistical reality. There's a weirdness happening right now in our society, the Boomers are hanging on, and of course you see this in national politics very clearly, and you see this in many other areas of the society. The Boomers are such a giant demographic wave, and then they're just not letting go of power, but at some point they're not going to have power anymore. When that happens, I think the Millennials just take over, because they are the other sort of mega-generation on the other side of that, and so I guess my pessimism would be that the next 50 years are going to be dominated by the Millennials in the same way the previous 50 have been dominated by the Boomers… That's not great. That's the headwind.

Like I said, we don't need to get to everybody. Change happens in the margin. The innovators, a very small number of people, have an outsized impact. The elite idea is a double-edged sword because, on the one hand, when you have elites that want to stop everything, they're very effective, even if that's not really what the broader population wants. On the other hand, you don't need that many Elon Musks to really fundamentally upending things. There is this sense, there are a lot of very talented Gen X-ers out there, there are a growing number of Millennials who are basically figuring out that something has gone wrong, and then Gen Z is coming

My theory on Gen Z is it's going to be kind of schizophrenic: there's going to be half of Gen Z that's going to be even more extreme than the Millennials, and they're going to be seriously out there on things, but I think there's going to be another big part of Gen Z that's going to just think that all the Millennial stuff is just basically deeply uncool and kind of stupid, and there's going to be a big rebellion back in the other direction, which is what tends to happen generationally. I think there's going to be a lot of incredibly sharp Zoomer entrepreneurs coming up here and engineers, and you see this in tech, it's happening right now, we meet them now every day, the 20-, 22-, 24-year-old founder where whatever is the catechism of the Millennial, they're just not doing it. I think the human capital on this is still tremendous. The English-speaking sphere, and particularly the US, is still the beacon for high-skilled immigration. It's still where all the really talented people from all over the world want to come.

Don't want to lose that.

Exactly. We don't. We have our immigration politics, and we have all the stuff that's happening, but still, there's only four countries globally that have routine inflows of high-skilled immigrants. There's only four. It's us, UK, Australia, and Canada. That's it. It's not happening anywhere else in the world, and I certainly don't see any reason to think that it's going to happen anywhere else in the world. And so we're going to continue to have that going on our side. The other reason for optimism is that technologies build on each other. We call this the idea of the stack, but there's a laddering of technologies. You get these technologies like the microchip and now AI and the internet, and people come up with thousands of new ideas for how to build on top. In particular, AI is a big one in that category, so it's going to be a tool that I think sharp people are going to be able to use to potentially cause very dramatic change in a lot of fields.

Marc, outstanding. Great stuff. I appreciate it. Thanks for coming on the podcast.

Thank you, Jim. A pleasure.

Hey, I have a new book out! The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is currently available pretty much everywhere. I’m very excited about it! Let’s gooooo! 🆙↗⤴📈

From the Introduction of The Conservative Futurist:

It's intriguing to see Andreessen express a desire to create 12 Elon Musks, given that Elon is one of the most vocal advocates for AI safety. Elon has consistently expressed concerns about the unchecked development of AI, and he has called for a pause on large-scale AI systems. It would be interesting to see Andreessen address his disagreement with Elon directly, rather than through hand-wavy dismissal of AI existential risk. Of course, sometimes Elon says crazy things, but based on this interview, it certainly looks like Elon has thought more seriously about this issue than Andreessen.