🚀 Faster, Please! Week in Review #37

The AI productivity paradox; teaching progress in high schools; advancements in human longevity; R&D policy; optimistic sci-fi; and much more!

My free and paid Faster, Please! subscribers: Welcome to Week in Review+. No paywall! Thank you all for your support! For my free subscribers, please become a paying subscriber today. (Expense a corporate subscription perhaps?)

Melior Mundus

In This Issue

Essay Highlights:

— The dynamo, the computer, and ChatGPT: Explaining today's productivity paradox— Let's add AP Progress to the high school curriculum

— The breakthroughs keep on coming. Now it's human longevity.Best of 5QQ

Best of the Pod

— A conversation with culture critic Peter Suderman on 'The Expanse' and the importance of optimistic science fiction

Essay Highlights

⚡ The dynamo, the computer, and ChatGPT: Explaining today's productivity paradox

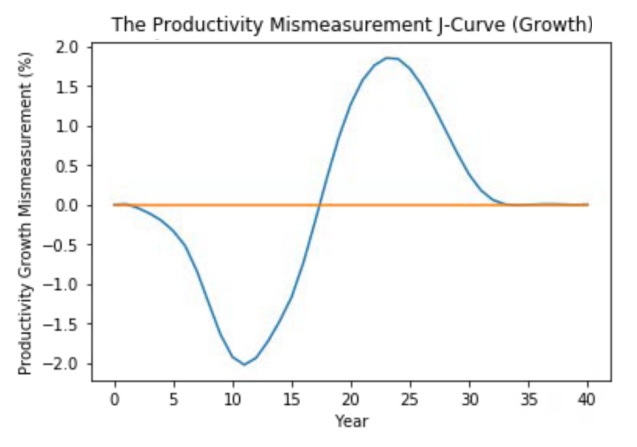

At some point, scientific discovery and technological innovation need to broadly and deeply affect how we live and work. Businesses and their workers needed to learn how to best use all this new technology. Because of that required learning and investment with important innovations, it may even seem like the innovation hurts productivity growth (at first) since new investment isn’t boosting output. As economists Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson explain, total factor productivity — a measure of tech progress — will be undermeasured when businesses adopt an innovation because to extract value, companies need to devote capital and labor to accumulating oodles of unmeasured intangible capital. Then, later, TFP will be overmeasured when those intangible investments start paying off with greater productivity. They call this dip and then surge the "J-Curve." Where are we on the AI/ML version of the Productivity J-Curve? I would note that even amid a decline in global venture capital investment, investors are still pouring money into AI companies like Open AI and Anthropic.

⤴ Let's add AP Progress to the high school curriculum

The exponential advance in technological progress, economic growth and productivity, and human welfare over the past two centuries is the defining fact of the past quarter millennium. It would be worthwhile to directly teach high schoolers about the Great Acceleration and Enrichment — the who, what, where, when, why, and how of it. There should be a class about it. One could imagine a course of study beginning with the Great Inventions of pre-industrial times, such as the compass and printing press, and then proceeding through the various stages of the Industrial Revolution: first (spinning jenny, steam engine, cotton gin, railroads, telegraph), second (internal combustion engine, telephone, lightbulb, automobile, aircraft), and third (semiconductors, mainframe computing, personal computing, and Internet). Of course, one might also want to include innovations that aren’t technical, such as the research lab and stock options.

🧬 The breakthroughs keep on coming. Now it's human longevity.

On Jan. 5, San Diego-based Rejuvenate Bio reported that it had used gene therapy to deliver Yamanaka factors — proteins that reprogram adult cells into pluripotent stem cells, which have the potential to develop into any type of cell in the body — into 124-week mice, modestly extending their lifespan. And on Jan. 16, the scientific journal Cell published a study that both explained a new model of how aging works — degradation in the organization and regulation of DNA — and suggested how aging might be reversed. How real is this? The rough consensus here seems to be that the results are intriguing, and if borne out in further research, could be a game-changer. But should we try to extend the human lifespan, going beyond just making the years we have healthier? Setting aside the more philosophical and existential arguments, increased lifespan could combat declining research productivity. Or imagine the gains from serial and successful entrepreneurs having time to launch one of two additional companies.

Best of 5QQ

Matt Hourihan is associate director of R&D and Advanced Industry at the Federation for American Scientists.

Are policymakers interested in supporting basic, curiosity-driven science or are they mainly interested in goal-oriented science?

I actually don’t think it’s super cut-and-dry. Basic, curiosity-driven science tends to be less controversial — the parties generally agree it’s an appropriate thing for government to be funding, and the agencies that fund it don’t tend to have political targets on their back. On the other hand, policymakers’ approach to science for practical goals can be uneven, depending on the issue, the year, the Members or committees involved…it seems to me that most policymakers have areas where they think government should be doing goal-oriented applied science, and areas where it should be left to industry, but there’s little consistency in the details. In an area like energy R&D, we’ve seen two committees led by the same party with wildly different ideas about what parts of the enterprise to fund or cut. Policymaker principles on what science to fund are not always coherent.

Best of the Pod

Peter Suderman is features editor at Reason magazine. He has written a number of fantastic pieces on science fiction including "The Fractal, Fractious Politics of The Expanse" in the December 2022 issue of Reason.

I think of a show that you have written a long essay about, and I've written about—not as intelligently, but I've written about it from time to time: the TV show The Expanse. And I find The Expanse to be optimistic sci-fi. It takes place in the future, a couple hundred years in the future. Humanity has spread out to Mars and the asteroid belts. There's certainly conflict. As an Expanse fan, someone just wrote an essay on it, would you agree that it’s optimistic science fiction?

I think it is, with some caveats. The first one is that it's optimistic but it's not utopian. And I think a lot of the argument against optimistic science fiction is actually not really arguing against optimism. It's arguing against utopianism and this idea that you sometimes see—there are hints of it sometimes in Star Trek, especially in Star Trek: The Next Generation—of, in the future humanity will have all of its problems solved, we won't have money, there will be no poverty. If you think about the Earth of Star Trek: The Next Generation's future, it's actually kind of boring, right? There isn't a lot of conflict. Writers eventually found ways to drive conflict out of conflicts between the Federation and other planets and even within the Federation. Because of course, they realized the utopian surface is just a surface. And if you dig down at all beneath it, of course humans would have conflict.

But I think a lot of the opposition to the idea of optimistic science fiction just comes from this idea of, “Well, wouldn't it be utopian?” And what The Expanse does is it tells a story that is, I think, inherently optimistic but really deeply not utopian, because it recognizes that progress is not an easy, straight linear line in which everybody comes together and holds hands, and there's a rainbow and My Little Ponies, and everybody just sort of sings, and it's wonderful. That's not how it works. In fact, the way that progress happens is that people have things they want in their lives, and then they seek, either on their own or in coalitions, factions, organizations—whether that's governments, whether that's the private sector, whether that's unions, whatever it is—they organize somehow or another to get the thing that they want. And sometimes they build things. Sometimes they build habitats.

And so this is something you see a lot of in The Expanse. Humans have colonized the solar system, as the story begins, and there are just all of these fascinating habitats that humans have built. Some of those habitats actually have problems with them. There are air filtration issues, where you have to constantly be supplying ice from asteroid mining. That sort of thing. Some of the main characters, when we first meet them, are working as ice haulers. Because of course, you would have to have some sort of trade of important resources in space in order to make these habitats work. And you could call this, “That’s not optimistic. In fact, a lot of these lives are sort of grubby and unpleasant, and people don't get everything they want.”

But I think that misunderstands the idea of progress, because the idea of progress isn't that suddenly everything will be happy and My Little Pony-ish. It's not My Little Pony. It's actually conflict and it's clashing desires and it's clashing ideals about how humans should live. And then it's people kind of working that stuff out amongst themselves, day by day, hour by hour, through coalitions, through organizations, through institutions, through technology, through politics sometimes. And all of those sort of tools and all of those organizational forms have a role. Sometimes they also have drawbacks. All of them have drawbacks to some extent. And then it's just a matter of how are people going work out the problems they have at the moment in order to get to the next place, in order to build the thing they want to build, in order to start the society they want to have.