🚀 Faster, Please! Week in Review #35

MLK and automation, '60 Minutes' and nuclear fusion, how science is broken, and much more!

My free and paid Faster, Please! subscribers: Week in Review is back! Oh, yeah! To my paying readers, thank you all for your continued support. For my free subscribers, please become a paying subscriber today! (Expense a corporate subscription perhaps? Think about it.)

Melior Mundus

In This Issue

Essay Highlights:

— The story of MLK and 1960s concerns about automation

— So aggravating: Gloomy '60 Minutes' downplays the chances of a nuclear-fusion economy. Of course, it did.

— The latest explanation for slow tech progress: science is brokenBest of 5QQ

— 5 Quick Questions for … economist Michael Strain on technological progressBest of the Pod

— A conversation with space journalist Eric Berger on NASA, SpaceX, and the future of space exploration⭐ Bonus!

— Michael Strain on noncompete agreements

Essay Highlights

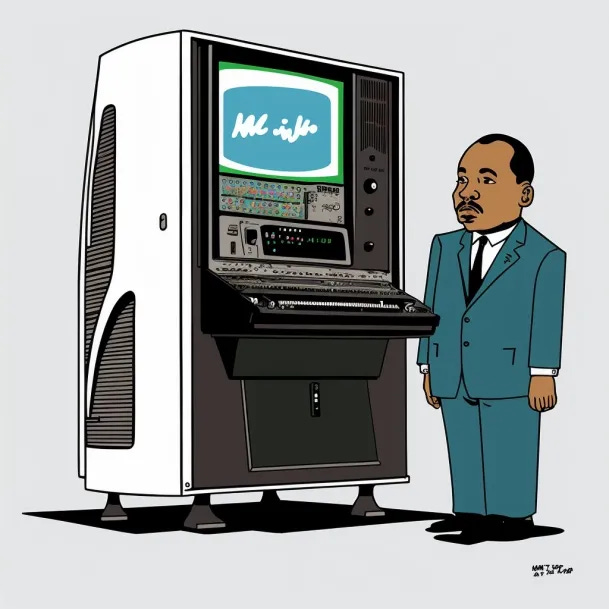

🤖 The story of MLK and 1960s concerns about automation

I was surprised to learn that in his final sermon, Martin Luther King Jr. mentioned the challenges of technological change, including the impact of automation. It’s another example of how concerns about robots taking all our jobs is hardly a modern phenomenon or one limited to the early days of the Industrial Revolution. Even in the boomy 1960s, they were big worries due to the rapid pace of technological change. LBJ even created a commission to study the issue. I think there's a lesson here: Even when progress is obvious, and the economy is firing on all cylinders, plenty of people will be worried about the downsides of that progress. For that reason, pro-progress types must continually make the case for the upsides of progress, as well as address legitimate concerns. Let me also point out this bit from his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, where MLK also wrote vividly on the subject of technology and human progress:

The years ahead will see a continuation of the same dramatic developments. Physical science will carve new highways through the stratosphere. In a few years astronauts and cosmonauts will probably walk comfortably across the uncertain pathways of the moon. In two or three years it will be possible, because of the new supersonic jets, to fly from New York to London in two and one-half hours. In the where do we go from here years ahead medical science will greatly prolong the lives of men by finding a cure for cancer and deadly heart ailments. Automation and cybernation will make it possible for working people to have undreamed-of amounts of leisure time. All this is a dazzling picture of the furniture, the workshop, the spacious rooms, the new decorations and the architectural pattern of the large world house in which we are living.

CBS's 60 Minutes reported Sunday on last month’s announcement of a stunning nuclear-fusion breakthrough. But I think the average viewer watching this entire segment might reasonably draw the conclusion that while some physicists in California did a cool science experiment that might win someone a Nobel Prize someday, this fusion announcement is otherwise pretty far removed from the big problems of today or even a generation in the future.

Overall, I give the 60 Minutes segment a C-. The good: All the explanatory stuff about the breakthrough. The bad: The overly negative look forward, unfortunately typical behavior by the Down Wing American media. To give this historical event and the grand possibilities ahead such shabby, unbalanced treatment right after giving Paul Ehrlich yet another high-profile platform — with no pushback — to offer his cranky doomsaying is dreadful journalism. I guess I shouldn’t have been so confident that 60 Minutes would produce anything better.

🧪 The latest explanation for slow tech progress: science is broken

The apparent slowdown in technological progress (whether measured by the lack of flying cars or slow productivity growth) has been explained by the exhaustion of Great Inventions, mismeasurement among economists, the exhaustion of new ideas, and government policy errors. The latest wave of explanations posits that science is broken, having become less productive in terms of generating significant advances in our understanding of how our world works.

The study that seems to have really put this issue on media radar today is a paper published earlier this month, “Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time,” by Michael Park, Erin Leahey, and Russell J. Funk. They find “that papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions.” Some ideas to get science back on track include funding lotteries, letting single reviewers push through high-risk and unorthodox projects, and establishing a "grand innovation fund" for moonshot projects.

Best of 5QQ

💡 5 Quick Questions for … economist Michael Strain on technological progress

Michael Strain is the director of Economic Policy Studies and the Arthur F. Burns Scholar in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute. He is also a member of the Committee on Automation and the Workforce of the National Academy of Sciences. In addition, Strain is the author of The American Dream Is Not Dead: (But Populism Could Kill It).

Pethokoukis: The Metaculus prediction community predicts labor force participation will be 46 percent in the 2040s. Metaculus also predicts that US labor force participation will drop below 10 percent in the year 2140. Do you think either of those forecasts is reasonable?

Strain: I think that there have been lots of predictions, going back to the famous Luddite episode, of new technologies making workers irrelevant. And those predictions have never come to pass. That should, I think, heavily inform any forecast of what workforce participation rates will be 20 years from now, or 120 years from now.

Second, I think that the basic economic logic that new technology increases national income and that human beings with a strong desire to consume goods and services will use that income for consumption, which will then create new opportunities for workers that are hard to imagine, is the right first guess for what will happen in the 2040s or in the 2140s. It is difficult for people to imagine going through their daily life without a smartphone in their pocket. But if you had come down to Earth in 1985 and told me that everybody would be walking around with a little computer in their pocket, and they would use this computer to communicate frequently and frivolously with friends, family, and coworkers, that they would use that little device to listen to other people having conversations, and that they would use that little device to reassure them about how to get from point A to point B — even though they travel between point A and point B on a very regular basis — I would've told you that you were crazy. And I would've been wrong. I suspect that in the 2040s and certainly in the 2140s, there will be many new goods and services that people consume that we cannot imagine sitting here right now. And that by increasing efficiency and productivity, new technology will free up workers to do new things. I'm sure when you began your career as a journalist, if somebody had told you that a big part of your week would be having conversations with people and those conversations would then be listened to by other people with very light editing on little pieces of plastic that they carry around in their pockets, that would've seemed rather odd to you. It may not have seemed odd to you, but you're very farsighted. It would've seemed odd to most people, I think. I would expect that general story to play out.

Best of the Pod

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica and author of 2021's excellent Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX.

Pethokoukis: When I was a full-time journalist, I'm pretty sure that when I would use the word “game changer,” editors would hate that. They would strike that word out. But Starship seems like it would be, if all those “ifs” are solved, it would be kind of a game changer. It's a big rocket.

Berger: If you think about it, everyone remembers the Saturn V rocket from the Apollo program, this massive launch vehicle. But all that came back to Earth was that tiny little capsule at the top. The first stage, second stage, third stage all fell into the ocean. The capsule came back, but then they were put in museums because they weren't reusable. The goal of Starship is for that whole stack to be reusable. So the first stage comes back, Starship comes back, and then you fly them again at some point. I think we're probably years and years away from those kinds of operations. But if and when SpaceX gets there, it does entirely change the paradigm of spaceflight that we've known since the late 1950s when Sputnik first went to orbit, which is now 65 years ago.

It's always been a premium on size — you want small vehicles that can fit on top of rockets in the payload fairings—and mass, because it costs so much to get to low-Earth orbit. If Starship works, it completely or almost completely removes those constraints: You can launch often, and it's got this huge payload fairing that you could fit elephants inside them, you could fit just massive structures inside of this thing. All of a sudden, the problem of scarcity, of getting stuff to orbit, no longer exists. It becomes not about the one thing we can do in orbit, but all the things we can do because it costs so much less to get there. And you can bring much larger structures.

Bonus

Michael Strain on whether we should we ban all non-compete agreements:

The issue of non-competes is one of those issues where people have strong feelings but there's just not a lot of evidence about their effects. For example, there's a lot of concern about non-compete agreements in the labor market for workers with relatively few skills or relatively less experience: If you work for this fast food restaurant, they make you sign a non-compete that you can't go work for a fast food restaurant down the street that's a competitor. That, on its face, seems hard to justify. I think it’s intended to be an anti-competitive practice, which reduces the competitiveness of the labor market.

It's an open question what the actual effect of that is. How much enforcement is there of those employment contracts? Do workers know they're signing those contracts? Does the hiring manager at the fast food restaurant down the street know that those contracts have been entered into, etc.? That being said, I think there is some solid evidence that non-compete contracts lead to reductions in wages. In part because I think they're hard to justify, and in part because they're at least intended to be a measure that reduces competition in those labor markets, it seems reasonable to me for governments to look at whether or not they're appropriate.

That's a separate question from whether the Federal Trade Commission has the authority to ban them. It's a separate question as to whether or not it makes sense for the Federal Trade Commission to ban them. The Federal Trade Commission is — or should be — concerned with the welfare of consumers. And it's not at all obvious to me that non-compete agreements are a threat to consumer welfare. I think the FTC’s proposal is on much weaker ground when you think about the labor market for workers with more skills, with specialized knowledge, and who earn significantly higher wages. It seems to me completely reasonable for Coca-Cola to say, hypothetically speaking, if you are one of the 30 people on Earth who has access to the formula for Coca-Cola and part of your job is to make it taste better, that you cannot quit your job at Coca-Cola and two weeks later go work for Pepsi. And if Coca-Cola wants to make that a condition of employment, and you want to accept that as a condition of employment, I don't see why the government should step in and say, “Well, we know better than either party in this transaction.”

Do you find the Silicon Valley versus Boston Route 128 arguments crediting California's non-enforcement of non-competes as an important factor in the rise of Silicon Valley persuasive?

I think that the effects of non-competes on innovation are even less well understood than the effects of non-competes on wages or on labor market dynamism. It seems to be that a company that employs highly educated, highly skilled, highly compensated, specialized workers is exactly the kind of company where it's most reasonable to have non-compete agreements in employment contracts.

Related, on peer review: https://open.substack.com/pub/experimentalhistory/p/the-rise-and-fall-of-peer-review