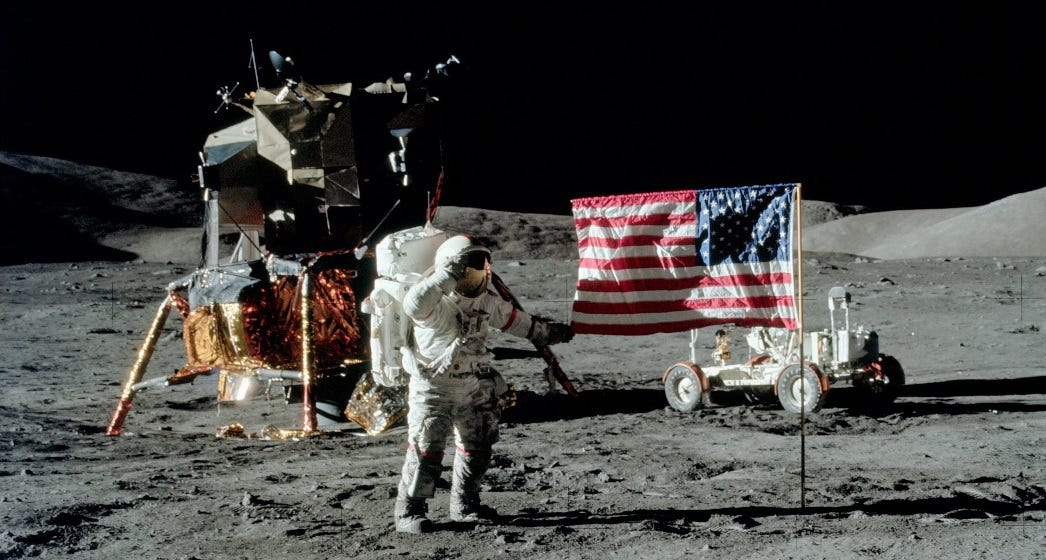

This month, December 2022, marks the 50-year anniversary of when man last stood on the Moon. NASA's Apollo missions were an awe-inspiring triumph of human achievement, but do people really care about space anymore? To discuss the wonder of space exploration, the virtues involved, and why robotic missions just aren't enough, I'm joined by Charles T. Rubin.

Charles is a contributing editor at The New Atlantis, where he has published several excellent essays on space exploration, his latest being "Middle Seat to the Moon" in the fall 2022 issue. He's also a professor emeritus of political science at Duquesne University and the author of several books, including 2014's Eclipse of Man: Human Extinction and the Meaning of Progress.

In This Episode

Will space become mundane? (1:29)

The case for astronauts (10:10)

Billionaires in space (14:29)

Sci-fi and the future of space (19:41)

Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Will space become mundane?

James Pethokoukis: In your New Atlantis essay, you write that “to make something routine is precisely to suck the wonder out of it, to make it uninteresting.” In regards to space exploration, is it important that people have a sense of wonder to it? Is it important to maintain public support for government efforts? And is it important in a higher spiritual sense, that we have a sense of wonder about the vastness of the universe outside our own little pale blue dot of it?

Charles Rubin: I think both of those are true, actually. It applies not just to government space program efforts, but also now to private space program efforts. The private ones obviously will operate in a market environment. Someday, I think it is hoped that such trips will not just be for immensely wealthy people, but will be for normally wealthy people. And they're going to have to have a reason to want to go into space. I think, as is true in many, many circumstances of tourism, it will be because there's something very cool and wondrous to be seen out there. That is certainly part of any justification — an important part, it seems to me, for both private space efforts and, of course, public space efforts. There are going to be many different reasons why people will support or be against a government-funded space program. But here also, I think that wonder plays an important role in attracting some kinds of people to those efforts who would otherwise not be attracted. The science of it, the technology of it — those are crucial things, but they're not going to appeal to everybody. But exploration and going where no human being has gone before: These are things that are going to have a broader appeal, I think.

I wonder, even if we get to the point where it's maybe not common that people take a quick trip into almost space or even at the point where they can have a vacation in orbit, even if you know people who have done that, I think there will still be a sense of wonder. I've done some traveling, probably a lot less traveling than some other people. But I'm pretty sure that when I go to Italy and see the Colosseum, or if I went to Australia and saw Mount Uluru, even though I am not the first person to do that and I know people have done that, I would still probably think those are pretty awesome.

I certainly hope that's true. It may be useful if I say something more about my concerns about routinization: I think that there are problems that will be faced as space travel gets more common and is available to more people. That will be a wonderful thing in terms of the success of the technology, but we will potentially find ourselves in a situation where it's going to be like flying in an airplane to Australia or flying in an airplane to Italy: I don't know how many people look out the window under those circumstances. And yet here you are flying at an immense height with extraordinary vistas to be seen around you, and we simply take it for granted.

I began to think about some of this in the way I do when I was going occasionally into New York City from New Jersey. I don't think this is a train ride that is known — well, I can know for sure — it's not known for its natural beauty, and I could look around me and see that people were doing almost anything other than looking out the window. But it's kind of an extraordinary ride. You're passing through suburban America, you're passing through decaying industrial areas. There's just a lot to be seen there. But of course, it's just a train ride so who really is going to be looking too carefully at what's going on around them? I'd like to see that in our space efforts we maintain that level of interest at all levels of the journey. And again, I think that's going to be an important part of both commercial and governmental success.

Is that possible? Is that an unavoidable downside? Some things are going to become common and there's always going to be a certain amount of people like yourself — I'm probably more like you in this; I always think it's cool the first time I see a New York skyline or taking a train and just seeing how one little town might be different; I enjoy that — and some people don’t, they will get lost in their phones or naps, and that's just the way we are. Different people have different preferences.

Yes, and that's fine. In fact, that's wonderful. But I don't think it's impossible to open a door that might otherwise be left shut. In other words, I think these are outlooks that can be cultivated. They're outlooks that can be encouraged. I think I was fortunate growing up: My folks took us on wonderful driving vacations, and when we started out was an era of auto suspensions where car sickness was still a major concern. We were actively discouraged from reading in the car, so we learned to pay attention to the landscape. And my mother was a great one for pointing things out, and she was never afraid to hide her own enthusiasm. And I didn't do such a good job with my kids, who became readers in the car. I kind of wish that were otherwise, but I probably could have done better. Again, I think there are attitudes that can be cultivated, there are expectations that can be created, that will perhaps allow more people rather than fewer to appreciate the wonders of space flight.

That reminded me of a book by the Nobel laureate Edmund Phelps called Mass Flourishing. And toward the end of the book, he talks a little bit about schools. And he's worried that we're not creating entrepreneurial — in the broadest sense of the word — risk-taking, adventurous children.

Are we creating with our current education system, do you think, the kind of people who can have a real sense of awe, a sense of wonder at what they see out of a window on a spacecraft or a space hotel?

That sounds like a last chapter I very much need to read. I agree. I think there are multiple tendencies in contemporary American culture that readily point us in directions that are not healthy. My hope would be something like this: that a serious, active, adventurous, risk-taking space program could serve something of the same function going forward in our time as that extraordinary, less than a decade served in the 1960s when the United States was on its way to the Moon. That really was inspiring. I look back on it and I think it's amazing. It took so short a time from the Kennedy speech to having people on the Moon. And people responded to that, it seems to me.

The case for astronauts

Frequent listeners will know that I love the TV show For All Mankind. And for those who have not watched it, it's an alt-history show where the space race never ends. The US and the USSR just keep racing, and it has all kinds of interesting side effects. And I remember, I think it was the end of season three, it flash-forwards — spoilers — to the early ‘90s. And what you see is this Martian vista, then you see an astronaut's boot take a step on that Martian vista. But some people don't get a thrill out of that. They think, “Fine. Build your space factories and space hotels and space stations, but anything beyond that, just send robots. Send robots to the Moon, send robots to Mars — do your exploration that way.” Certainly, you could do some exploration more cheaply if it was just robots. Is it worth the risk to be sending people beyond the Moon?

I want to acknowledge your point and say, yes, there are people who simply aren't going to find any kind of appeal in this. And that's okay. I just would like to see a situation where those whose heartstrings can be plucked by this sort of thing can express it that way and can understand themselves that way. An for example, NASA perhaps be a little more forthright in stressing the adventurous and the risk-taking part of its program rather than, as it has been in the past, tending to downplay the risk. I'm not talking about making things more risky. I'm talking about admitting the risks that are actually there.

We mentioned a current essay, but you had another one which was great, “The Case Against the Case Against Space.” I'm quickly going to read a few sentences from that:

“We should want heroes, but heroism requires danger. That many professed shock when the idea was floated that early Mars explorers might have to accept that they would die on Mars is a sign of how far we miss the real value of our space enterprise as falling within the realm of the ‘noble and beautiful.’ It would be better to return in triumph, to age and pass away gracefully surrounded by loved ones, and admired by a respectful public! But to die on Mars — to say on Mars what Titus Oates said in the wastes of Antarctica, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’ — would be in its own way a noble end, a death worth commemorating beyond the private griefs that all of us will experience and cause.”

That seems to me a countercultural notion right now: that it's worth it. There are worse things than to die in that pursuit.

It is a countercultural notion, but I think it's worth trying to… And by the way, thank you for that.

I've quoted that passage in various things. I just love it.

But we can work towards creating a world where it is at least not as unusual as it might be today. I think there is to some extent a kind of natural appeal of heroism, a natural admiration of risk taking. And we can work to bring that out with respect to the space program. And yes, of course, we should pride ourselves on the fact that we are not expending lives lightly and that we do everything we can to bring our astronauts back. But there also has to be a recognition that it isn't always going to work that way. And just because lives will be lost, that does not in any way diminish the value or the meaning of the enterprise.

Billionaires in space

We have this “Billionaire Space Race.” Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Branson: They all seem to have very different goals. Musk and Bezos, particularly, have a far more expansive vision of what they're trying to do than somebody like Richard Branson. But they're certainly describing what they're doing differently. Elon Musk has talked about how we're going to be a multi-planetary civilization, have colonies on Mars. And Bezos has not tended to talk like that. He talks about creating an orbital economy, moving heavy industry into orbit: a much more grounded description. I wonder if Bezos does that because he just wonders how much interest people really have in space exploration. I'm not sure what my question is, but certainly it seems like they've taken different stances. And I'm wondering if there's an underlying concern that even though we love science-fiction films, there's just not that kind of interest in space?

In a way, I think that the fact that interest in space is limited is actually something which Elon Musk's vision accommodates better than Jeff Bezos' vision. Jeff Bezos does imagine vast numbers of people moving up into those orbital colonies such that the Earth is significantly depopulated largely for the sake of ecological integrity. That presumes a huge interest in people moving into space. And to my mind, frankly, it’s quite unrealistic.

But what is Musk talking about? Musk is talking about something that we know well. I understand from that book I criticized that there are problems in analogizing Earthly exploration to space exploration, but there are still similarities. We're talking about sending a small number of people on our behalf for the sake of exploration, for the sake of adventure, for the sake of the expansion of knowledge. That can be done with a relatively smaller constituency than a vision like Bezos’, which requires just about everybody somehow to buy into it. Even when we start talking about colonization of Mars, as Musk likes to talk about, even that can be a minority taste and yet still lay the groundwork for extraordinary possibilities of a human future.

William Shatner recently did a quick jump into space and back with Jeff Bezos, and there was a lot of attention paid to his reaction. William Shatner said after his trip to space: “The contrast between the vicious coldness of space and the warm nurturing of Earth below filled me with overwhelming sadness. … My trip to space was supposed to be a celebration; instead, it felt like a funeral.” What do you make of that reaction?

I think that his unstudied reaction immediately following the flight — I think what you're quoting is a later reflection on his experience — was more telling. Whether or not there was an element of sadness, he was moved to an extraordinary extent by his experience. And I think that's appropriate. Of course, people are going to be moved in different ways and he is certainly entitled to reflect back on his experience and put a much darker tone on it subsequently than he put on it at the time. There was some of that in what he said at the time, but I think his vision has gotten darker over the course of the last months. People aren't all going to be moved to the same…

I love the idea of space exploration and that did not bother me at all. It made me appreciate Earth. It made me think we have to make sure Earth works right now because there's no place for us to go. I can understand that, thinking about Earth and are we taking care of it enough? That's totally fine. I don't think it means that we shouldn't explore space and try to go out there. But to me that's a totally reasonable reaction, and maybe also a reaction I might have if I was in my ‘90s and probably thinking more about having probably far fewer days ahead than behind.

Yes. That's a nice point.

Sci-fi and the future of space

Are there books, TV shows, movies, and science fiction that you think present thoughtful visions about space or even about the future of space exploration or the future in general?

Let me mention two things. I haven't gotten nearly as deeply into For All Mankind as you have, but I'm enjoying it tremendously. The show that I love so much that I haven't been able to bring myself to watch yet the last few episodes is The Expanse. I think it is actually a very thoughtful and compelling vision of a future. Lord knows, in some ways it's a terrible future. I don't want to do a lot of spoilers, but nonetheless, I think it has the root of the matter in it, that this is what a human future in space looks like. And there are going to be heights and there are going to be depths. But the opportunities for new venues in which to experience those kinds of heights and depths, there's going to be something extraordinary about it.

The other thing is, there's this wonderful coffee table book. It's called Apollo Remastered by a photographer named Andy Saunders. And he has taken some familiar and some hitherto-unseen NASA footage and processed it using modern techniques. And so the pictures are beautiful in themselves, but he also has done interviewing of some of the surviving astronauts. He has, I think, a wonderful eye and ear for the adventurism aspect of space exploration. And he gets some astronauts talking and commenting on things which I was a little surprised to hear. It made me think differently about some of those Apollo astronauts than I had up to that time. It's a lovely book visually and also just quite stimulating in terms of its vision of what was actually going on among the astronauts of that period.

Since you mentioned The Expanse and it's a show I really like: I've written a little bit about it, and I got into a little bit of a back-and-forth with people because I described it as a “future-optimistic” show. And people are like, “How could you say that? There's still conflict and war, and there's inequality?” Yes, because we're human beings, and whether we have fusion drives, that's going to be there. My idea of a better future isn't about creating a race of perfect near gods. It’s that we keep going on.

When I think about how much conversation is about the ecological destruction of the Earth and that we're not going to have a future, to have a show that says, “A lot of things went wrong, but we're still here.” In The Expanse, it’s clear there has been climate change. I think there's a giant sea wall protecting New York. There are problems, and we solve problems. And maybe our solutions cause more problems, but then we'll solve those and we just keep moving forward. Humanity keeps expanding and we keep surviving. And that's pretty good to me. That’s my kind of future-optimism. As much as I love Star Trek, I don't require an optimistic future to be one where there's absolute abundance, no poverty, we all get along all the time.

I think that's beautifully observed. I agree 100 percent. I don't think I would like to live on the Mars of The Expanse. I don't think it's my kind of place.

A lot of tunnels. You're living in a lot of tunnels.

But Bobbie is just an extraordinary person. She's very Martian, but she isn't entirely limited by her Martianness. She's so competent and capable and just admirable in all these ways which a future person, one hopes, could turn out to be admirable. That's very beautiful. And yes, there are terrible traitors on Mars, traitors to humanity on Mars, too. But just as you say, it allows us to continue to lead human lives in these new and extraordinary settings and stretches. If that were to be the future, it stretches our capacities, it stretches our minds, it challenges us in ways which I think are good for us.