Elon Musk vs. Bernie Sanders about space; geoengineering isn’t just for mad scientists; R&D on the rise; and more ...

Quote of the Issue: “Frank O’Connor, the Irish writer, tells in one of his books how, as a boy, he and his friends would make their way across the countryside, and when they came to an orchard wall that seemed too high and too doubtful to try, and too difficult to permit their voyage to continue, they took off their hats and tossed them over the wall—and then they had no choice but to follow them. This nation has tossed its cap over the wall of space, and we have no choice but to follow it.” - President Kennedy, November 21, 1963

In this Issue:

🦄 Elon Musk vs. Bernie Sanders: When unicorns start fighting elephants and donkeys (398 words)

🧪 What does economic research say about the benefits of government science research? (344 words)

🌞 Geoengineering isn’t just for aspiring mad scientists and supervillains anymore. Actually, it never was. (383 words)

⭐ Best of the Pod: Talking scientific freedom with Don Braben (403 words)

🦄 Elon Musk vs. Bernie Sanders: When unicorns start fighting elephants and donkeys (398 words)

Elon Musk and Bernie Sanders sparred on Twitter last week about space. And it went about how you might imagine. The democratic socialist senator from Vermont making his usual points about wealth inequality. And Musk, well, going the Full Musk, offering not so much the 30,000-foot view as the 160-million mile view: “I am accumulating resources to help make life multiplanetary & extend the light of consciousness to the stars.”

There was a time when the Left was infused with techno-optimism, even techno-utopianism. Science and its tools would recreate and improve man and society. At least that’s what they thought before World War II amid the booming Second Industrial Revolution. To be a “progressive” was to believe in econ/tech progress. As H.G. Wells — a socialist and futurist as well as creator of the sci-fi genre — said at the turn of the last century: “Everything seems pointing to the belief that we are entering upon a progress that will go on, with an ever-widening and ever more confident stride, forever.”

By 1945, however, Wells was writing how his optimism had been replaced by a “stoic cynicism.” Winston Churchill’s “perverted lights of science” phrase — from his June 1940 speech to the House of Commons — seemed apt when looking at the fruits of pre-war advances in physics (the atomic bomb) and biology (eugenics and the Holocaust).

And by the 1960s, the Left was infused with concerns both social and environmental (Silent Spring was published in 1962) that clashed with economic growth and technological progress. When President Nixon began winding down the Apollo program in 1970, the New York Times editorial board reminded readers, “Throughout the last decade, this newspaper opposed … Project Apollo on the ground that too much money was being diverted from urgent social needs.”

And that through-line extends to the current moment. It helps illuminate why too much of the modern Left disdains nuclear power, the space economy, and billionaires — even if their wealth is entrepreneurial rather than inherited. This zero-sum philosophy centered around scarcity rather than abundance (we need more energy not just making current energy generation carbon free) also explains why Silicon Valley fits so awkwardly on the Left. Too bad this disruption-averse stasis view is also now infecting the Right as the GOP rebrands as a “workers party.” (Much more on this in future issues.) Missed political opportunity, I think.

🧪 What does economic research say about the benefits of government science research? (344 words)

“Never waste a crisis” can be spun by politicians to the good or to the ill. Thankfully it’s the good sort at play in a new science research bill from Representative Frank Lucas, an Oklahoma Republican. His Secure American Leadership in Science and Technology Act cites two crises as justification: China’s “pursuit of technological supremacy” and the need for a “clean [energy] economy that stays ahead of foreign competition.” Pretty good sales pitch.

Democrats also have some big ideas when it comes to more science funding, as well as investing in strategic technologies. (I wrote about this last week.) So what do we think we know about the economics of federal spending on science research? Seems like a good question to ask before spending hundreds of billions, if not trillions, eventually.

Two big questions: First, how do changes in public spending affect private spending on R&D? In a 2018 literature review, the Congressional Budget Office took the position that “federal spending for R&D has a small but noticeable positive effect on the amount of money the private sector spends on R&D.” Indeed, a more recent study finds a significant “crowding in” effect where public spending leads to more private spending. Second, does more government R&D actually boost economic growth? In that same analysis, the CBO “expects that R&D (as well as federal investment more generally) increases aggregate economic output mainly by gradually boosting private-sector productivity in the longer term.”

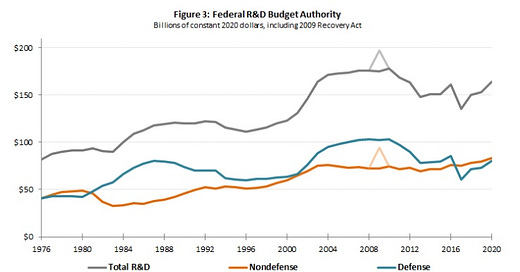

Of course, private and public investment tend to focus on different stages of R&D, the former is more early stage, the latter more about product development and commercialization. Total US R&D spending is pretty strong, now surpassing 3 percent of the American economy for the first time in 2019, according to a new OECD paper. But as an AAAS report on the study adds, “The bulk of U.S. R&D growth was likely driven by industrial investment.” So an opportunity for government to step up. This AAAS chart gives a good feel for funding growth over time:

🌞 Geoengineering isn’t just for mad scientists and supervillains anymore. Actually, it never was. (383 words)

Get ready for a big “we told you so” from conspiracy theorists who think Bill Gates is an evil genius manipulating COVID-19 vaccines to slip microchips into their blood. Turns out the centibillionaire Microsoft co-founder is helping fund a project to dim the sun! Talk about a prima facie case of Lex Luthor-level supervillainy.

Gates isn’t trying to chip America, of course. But he is interested in ways of blocking sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface by reflecting it. And that’s a good thing. The US and the world may need a radical “break the glass” option in case of extreme climate emergency. So Gates and other private donors are backing Harvard University’s Solar Geoengineering Research Program. One small project about to begin will experiment with releasing a small amount of calcium carbonate dust into the air.

Solar geoengineering was once treated like a mad scientist’s diabolical scheme. Less so today. A new report from the National Academies of Sciences — while emphasizing the approach is no substitute for reducing greenhouse gas emissions — recommends America “pursue a research program for solar geoengineering … to better understand solar geoengineering’s technical feasibility, possible impacts on society and the environment, public perceptions, and potential social responses — but it should not be designed to advance future deployment of these interventions.” So still a bit of squeamishness about the idea, as that final bit shows.

But we all need to get over that hesitancy. If climate-change danger is as potentially existential as some contend, all options need consideration. The late Harvard economist Martin Weitzman once wrote that climate change was characterized by “deep structural uncertainty in the science” and thus the “probability of a disastrous collapse of planetary welfare from too much CO2″ is both ”non-negligible” and ”not objectively knowable.”

While Weitzman acknowledged the law of unintended consequences, he thought the tail risk of climate change too great to forgo certain technologies. And even if rich-but-nervous nations did just that, geoengineering might prove so cheap that desperate middle-incomers might go it alone. All the more reason for the U.S. to pursue a comprehensive research agenda to better understand the nascent technology. Otherwise the “we told you so” might come from geoengineers in a sizzling future when sweaty policymakers break the glass and there’s nothing inside.

⭐ Best of the Pod: Talking scientific freedom with Don Braben

How can research institutions promote growth, other than simply spending more money on basic R&D? I recently chatted about this subject on my Political Economy podcast with Don Braben, who argues that we need to promote scientific freedom by easing up on the strictures of peer review and the demands of obvious applicability. Braben is an honorary professor and vice president of research at University College London. He’s the author of several books, including Scientific Freedom: The Elixir of Civilization, which was originally published in 2008 and was, in 2020, republished by Stripe Press. A bit from our chat:

Pethokoukis: I‘d like to see more transformative technological progress and scientific discovery, but it seems like the only solution I keep hearing for that is, “Let’s spend a lot more X” — whether “X” is basic research, basic-plus-applied research, or maybe even some sort of industrial policy. Basically it’s, “Let’s spend a lot more money on something.” Now, while that may be necessary, I think your book makes the case that simply spending more money is not a sufficient solution.

Braben: That’s right, it’s not. We need to look at what we’ve done over the past century. Over the past few decades, academics have had to adjust to radical change. Before the 1970s, most academics did not have to prepare proposals for what they wanted to do. Provided their requirements were modest, they could simply press on with whatever they had in mind. The harvest from this unconstrained academic freedom was spectacular and transformed everyone’s lives.

Such discovery started in the beginning of the 20th century. After the heroic efforts of James Clark Maxwell, who finally unified the apparently unrelated fields of electricity and magnetism in the 1860s, Max Planck began the 20th century — after more than 20 years of study — with his unexpected and transformational discovery of energy quantization, which subsequently revolutionized the study of the sciences. His breakthrough inspired others to create their own unpredicted technologies like the laser and myriads of spinoffs, countless components of the electronic and telecommunications revolutions, nuclear power, biotechnology, and medical diagnostics galore — all of which are now indispensable parts of life.

Yet all of these discoveries depended on a scientific freedom we no longer have. And so, while spending large amounts of money would certainly be very nice for some scientists, it would not solve the problem that I’m trying to address.

Next Steps

The delusions of techno-futurists who ask: crisis, what crisis? - Financial Times | Columnist John Thornhill dings tech investors like Sam Altman for their AI + UBI = Utopia view. It wildly overestimates the near-term impact of artificial intelligence and underestimates the difficulties of policy change. Thornhill: “Their efforts would be better spent figuring out how best to use AI to enhance human creativity and innovation in small, discrete and meaningful ways, rather than render it redundant.”

Why it will be years before robot butlers take over your household chores - The Washington Post | They’re still too dumb, too clumsy, too dangerous to be useful in the home. “The reason why iRobot doesn’t sell a robot with an arm is because we don’t know where anything is,” said Colin Angle, chairman and founder of iRobot. But maybe something within the decade. Amazon, for one, is still a believer with its Vesta home robot project. (Roboticist Rodney Brooks loved this piece, by the way.)

10 Breakthrough Technologies 2021 - MIT Technology Review | Messenger RNA vaccines (could help fight cancer) … GPT-3 (best large natural-language computer model to date) … TikTok recommendation algorithms (rivals scrambling to catch up) … Lithium-metal batteries (could extend the range of an EV by 80 percent + rapid recharging) … Data trusts (“a potential solution to long-standing problems in privacy and security”) … Green hydrogen (a clean economy possibility thanks to “rapidly dropping cost” of solar and wind energy) … Digital contact tracing (lots of post-pandemic potential) … Hyper-accurate positioning (new possibilities, from “landslide warnings to delivery robots and self-driving cars that can safely navigate streets”) .… Remote everything (tele-health and tele-education in developing world) … Multi-skilled AI (combine computer vision + audio recognition can sense things + natural-language algorithms).

Long-run contact with immigrant groups, prejudice, and altruism - Vox EU | A fascinating study, especially given the importance of immigration to economic growth. From the analysis: “Taken together, our results indicate that long-term contact – across all types of everyday interactions over the course of decades – makes the majority group less explicitly and implicitly prejudiced, less politically hostile, and more altruistic toward minority immigrant groups.”

Bright side of the moonshots - The Economist | “These innovations will have big consequences. General-purpose rna medicine asks new things of firms and regulators— as do other platforms, including some forms of gene therapy. Regulators will need to take advantage of the fact that, say, a malaria vaccine and a sars-cov-2 vaccine are both made on the same platform by streamlining approval for them, while continuing to ensure safety.”