America, China, and industrial policy; AI and UBI; The Chart of the Future, and more ...

Quote of the Issue: “The fundamental [Enlightenment] belief that the human lot can be continuously improved by bettering our understanding of natural phenomena and regularities and the application of this understanding to production has been the cultural breakthrough that made what came after possible.” - Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth

🏭 America embraces capitalism with Chinese characteristics

Industrial policy (broadly: government favoring certain sectors, specific technologies, or even companies for some ostensible strategic purpose) has long had a home on the American left — but now also growing support on the right as the GOP seeks to rebrand itself as a “workers party.” Its moment seems to have arrived. (Again.)

Democrats are planning a big legislative package around America’s intensifying economic competition with China. The centerpiece seems likely to be the Endless Frontier Act. The 2020 version would have revamped the National Science Foundation into the National Science and Technology Foundation. It would also have boosted funding by $100 billion (over 5 years), created regional tech hubs, and pushed the new NSTF to focus on key geostrategic tech sectors such as 5G, AI, biomedical research, and quantum computing. Whatever the 2021 version looks like exactly, it will unlikely be the final bite at the R&D apple. Maybe/probably more to come in the big Biden infrastructure and climate change bill this year.

If I had the “con” side in a debate, I would open with a brief economic history lesson: the failure of 1980s Japan Inc., the failure of the Concorde, the failure of the French internet. I would then highlight the success of the more market-driven, bottom-up American model of experimentation and permissionless innovation. Where is Europe’s Big Tech, my friends? I would finish with a preemptive framing of Silicon Valley’s success. Government involvement there? Sure. But there was no central plan. A happy, one-off accident. And it’s a big leap from a four-node computer network to Amazon Prime.

If I were on the “pro” side, however, I would give a short update on current events: China just announced it will increase its annual R&D spending by 7 percent annually for the next five years, with a special focus on next-generation AI, quantum information, brain science, semiconductors, genetic research and biotechnology, clinical medicine and health, and exploration of deep space and sea. Can America risk a world where China becomes the dominant technological power — and thus the dominant economic and military power? What about a Firefox scenario where China makes a technological leap that totally upsets the global balance? A lower corporate tax rate is not enough!

But here’s the thing: As economist Phil Levy has put it. “Reliance on invisible hands is discomfiting.” Politicians want to cut ribbons, pass bills, be seen taking action. Tough to run campaign ads around successfully maintaining a pro-growth, pro-entrepreneur policy ecology (supply public goods, keeping investment taxes low and regulation light) — especially when you’re confronting a major geopolitical challenge.

If Washington is headed in this direction, my baseline concern is that this effort not undermine America’s existing innovation advantages. It’s a concern that the recent just-released report from the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence makes some effort to address. The document pushes an AI-themed industrial policy, including: create government-financed innovation clusters, use government purchasing to boost strategic tech, and implement refundable investment tax credits so that the U.S. semiconductor sector stays ”two generations ahead of China.”

But the report also values and seeks to improve what America already does well, such as attracting global talent and basic research. To the latter point: It would create a new National Technology Foundation, rather than bolting a new and possibly distracting mission onto the NSF. Clearly, not undermining the current NSF mission was firmly in mind. Such an instinct should run throughout the evolving effort. Oh, and don’t forget about taxes and regulation, too.

💡One more thought about industrial policy

I recently chatted with Daniel Gross, an assistant professor at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business and a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He’s the author of several papers examining innovation policy in the World War II era, the most recent of which is “Organizing Crisis Innovation: Lessons from World War II,” which he co-authored along with Bhaven Sampat. Here’s a snippet that touches on the issue of industrial policy and favoring certain technologies that everyone know are the most important for our future:

Pethokoukis: One of my concerns is that we’ve gotten so confident in thinking that we know where funding should go — whether it be to vaccines, AI, or clean energy technology — that we’re going to forget about basic research. Basic research seems a bit off-point right now when we’ve got so many “obvious” problems to deal with.

Gross: I agree, there are many risks in that thinking. For one, we could forget about basic research entirely. Or we might divert resources away from other fields that might yet hold promise, which would also be detrimental. One of the questions that I reflect on in the World War II context — and also think about today as pharmaceutical research is diverted from problems of nevertheless long-standing importance to focus more on COVID — is what might’ve been left behind?

Let’s just take the World War II context for a moment. You had the scientific establishment — say, the country’s physicists — shifting from whatever work they’re doing before to instead focus their energies on atomic fission and radar. While we might celebrate that effort because it’s easy to see what we got from it, it’s difficult to know, and easy to overlook, what we might have also left behind.

That’s one of the questions that I’m continuing to explore in my research: What actually might’ve been crowded-out as the research and technological development we now celebrate was crowded-in?

🤖An AI twist on Silicon Valley’s love affair with the UBI

Sam Altman, CEO of nonprofit OpenAI and former president of startup accelerator Y Combinator, has proposed a new flavor of universal basic income. He would (a) tax biggish companies 2.5 percent of their market value in the form of company shares, (b) tax 2.5 percent of the value of all land in the form of dollars, and then (c) funnel all that dough into the American Equity Fund. All American adult citizens would receive payment in dollars and company shares, no strings attached.

This plan is premised upon two key beliefs. First, we will soon experience an “AI revolution” that “will generate enough wealth for everyone to have what they need, if we as a society manage it responsibly. … The technological progress we make in the next 100 years will be far larger than all we’ve made since we first controlled fire and invented the wheel.”

Second, despite that explosion of growth, most people will be worse off because there will be fewer opportunities for humans to generate economic value. So we’ll need a new social contract to spread the wealth by giving everyone a stake in the economic system. Altman: “If everyone owns a slice of American value creation, everyone will want America to do better: collective equity in innovation and in the success of the country will align our incentives.” If implemented, we might all be getting a $13,500 dividend from the fund as soon as a decade from now.

Altman seems to be telling a story of technology replacing workers. But you can tell another story, one of technology enabling workers, complementing existing jobs, and creating new tasks. It’s a framework that economist Daron Acemoglu has been exploring in recent years. Acemoglu: “When railroads came and replaced the horse-drawn carriages, we created a whole host of new occupations associated with the railroad; engineers, conductors, maintenance workers, financiers and managers. In the same way that when computers came we created a whole host of computerized radiology, computer engineers, software developers and very different versions of many of the tasks that were manual.”

I’m not sure the evidence yet suggests such a radical break in economic history that the displacement scenario totally overwhelms the enabling scenario. But I will bookmark Altman’s idea just in case.

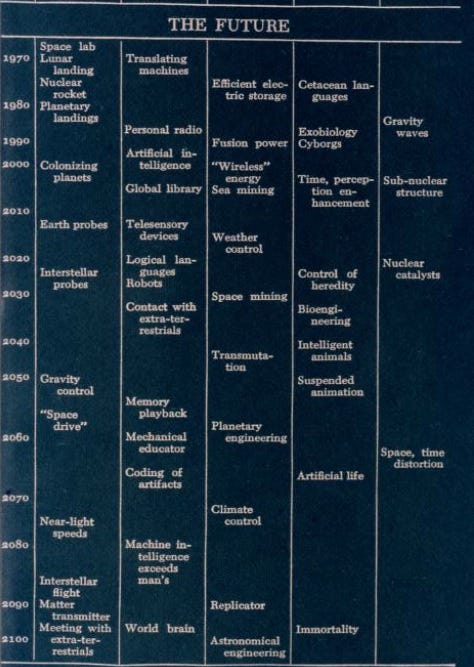

😞 The future we never got, decade by decade, according to Arthur C. Clarke

It’s not just a lack of flying cars and Moon colonies. There are a host of technological developments that never happened or happened a lot later than the techno-optimists of the 1960s predicted. In his 1967 book, Profiles of the Future, author and futurist Arthur C. Clarke helpfully created a timeline of what he thought might happen and when it might happen, seen below. (A caveat from Clarke: “The chart, of course, is not to be taken too seriously.”)

Next Steps

How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially? | Our World in Data

What if we just … buried carbon emissions underground, forever? | Slate

The Internet Is Not Just Facebook, Google & Twitter: Creating A 'Test Suite' For Your Great Idea To Regulate The Internet | Techdirt/Mike Masnick

10 Breakthrough Technologies 2021 | MIT Technology Review

Ageing can be cured—and, in part, it soon will be | The Economist