💥 What the 'Bison Shock' of the 1800s can teach us about economic growth today

Geographic mobility has always been an important way of dealing with economic disruption. Also: Why wolves are like startups

One of this newsletter’s core themes is that our climate-change problem is really a clean-energy problem. Yet while I’m enthusiastic about the potential of emerging energy technologies — advanced nuclear fission, enhanced/advanced geothermal, nuclear fusion — I’m also perfectly willing to accept that wolves and beavers have a role to play here. No, not on the clean energy side of things, but helping nature adapt to a changing climate. Inside Climate News reports:

Restoring and protecting beaver and wolf populations and reducing cattle grazing across large tracts of the western United States could be a big part of meeting President Joe Biden’s goal of conserving at least 30 percent of the country’s lands, lakes and rivers by 2030, a new study suggests.

Both animals are keystone species that help shape the landscapes they live in, and bringing them back in a big way could help forests and streams struggling to adapt to rising temperatures and aridification, a team of 20 scientists concluded in a paper published Tuesday in the journal BioScience.

An expanded wolf population would thin out herds of elk and deer that hamper forest regeneration when they browse on tender young trees. Beavers would modulate flows along streams and rivers by building dams that create areas of spongy soil that absorb water during heavy rains and release it back slowly in drier times.

Project Beaver and Wolf is a less ambitious version of other efforts to use animals as an adaptation and mitigation tool. Yes, it would be intrinsically supercool to de-extinct the woolly mammoth by genetically modifying Asian elephants with cold-weather traits — more subcutaneous fat, thicker coats, smaller ears — and have them roam the Siberian tundra for the first time in 10,000 years. But there would be a practical purpose as well: Those beautiful beasts would help recreate the Siberian landscape of 10,000 years ago by knocking down trees and restoring the grasslands of long ago. It’s an environment that would “reflect more of the sun's warming rays and eliminate insulating snow and forests so the ground cools more. And that means the ground will stay frozen instead of releasing its current store of carbon dioxide and methane greenhouse gases.”

The Way of the Wolf

But let’s get back to the wolves of the West. Their ability to shape their natural environment also provides an economic lesson. Several years ago I watched a fascinating report on how the 1995 reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park — after a 70-year absence — altered the park’s entire ecosystem. These apex predators also, the report explains, “give life to many others.” And not just by reducing and controlling the deer population. Just by being there, the wolves changed the behavior of the deer and that led to a “trophic cascade” which caused an explosion in the number and variety of plants and animals … which also then changed the paths of the rivers. “So the wolves, small in number, not only transformed the ecosystem of Yellowstone National Park, but also its physical geography,” the documentary concludes.

In the US economic ecosystem, startups are the wolves. They generate innovation (and jobs) and force incumbents to improve or die. They change the business landscape — creating a healthier, more vibrant economy in the process.

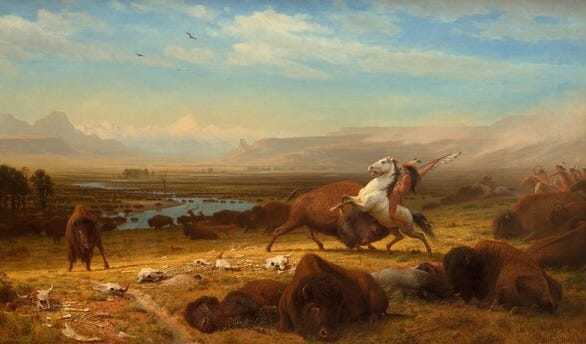

The bison were really missed when they were gone

Similarly, we can learn some economic lessons from the rise and fall of the American bison. Here’s a quick summary of the new NBER working paper “The Slaughter of the Bison and Reversal of Fortunes on the Great Plains” by Donn. L. Fei (University of Victoria), Rob Gillezeau (University of Toronto), and Maggie E.C. Jones (Emory University):

In the late nineteenth century, the North American bison was brought to the brink of extinction in just over a decade. We demonstrate that the loss of the bison had immediate, negative consequences for the Native Americans who relied on them and ultimately resulted in a permanent reversal of fortunes. Once amongst the tallest people in the world, the generations of bison-reliant people born after the slaughter lost their entire height advantage. By the early twentieth century, child mortality was 16 percentage points higher and the probability of reporting an occupation 29.7 percentage points lower in bison nations compared to nations that were never reliant on the bison. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and into the present, income per capita has remained 28 percent lower, on average, for bison nations. This persistent gap cannot be explained by differences in agricultural productivity, self-governance, or application of the Dawes Act. We provide evidence that this historical shock altered the dynamic path of development for formerly bison-reliant nations. We demonstrate that limited access to credit constrained the ability of bison nations to adjust through respecialization and migration.

You may have heard of the “China trade shock,” how US communities that produced goods competing with Chinese exports, especially furniture and textiles, suffered long-lasting economic pain and social disruption in the early 2000s. Well, this paper is about the “Bison shock” for native Americans. It notes that by 1900, the stock of North American bison had declined to around 500 from maybe 30 million before European settlement. And while in some places the decline was gradual, in others it occurred during just a decade or so of mass slaughter. Either way, it was a civilization-altering event:

For the Native Americans of the Great Plains, the Northwest, and the Rocky Mountains, this meant the elimination of a resource that served as their primary source of livelihood for over 10,000 years prior to European settlement. For many nations, the bison was used in almost every facet of life and not only as a source of food: skin was used for clothing, lodging, and blankets, and bones were used for tools. Historical and anthropometric evidence suggest that these bison-reliant societies had living standards comparable to or better than their European contemporaries. When the bison were eliminated, the resource that had underpinned these societies vanished … The slaughter of the bison led to one of the largest and most rapid losses of a critical industry in North American history.

Thinking of this event in economic terms helps generate insights and conclusions that are widely applicable to other one-time shocks. While the loss of the bison was an extraordinarily large economic shock, it wasn’t the only one in American history. I earlier mentioned the China trade shock, but Fei, Gillezeau, and Jones also cite the decline of the American coal and steel industries in the 1980s and the collapse of the North Atlantic cod fishery in the 1990s. When such shocks happen, the key to adapting often involves access to credit, which can help in starting new businesses or finance a move to more prosperous areas.

The loss of the bison was an enormous economic shock to the communities that had once relied on it and it is clear that limited early access to financial institutions, coupled with the federal government’s policy towards Native Americans through the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries ultimately prevented the formerly bison-reliant nations from adjusting to this shock over time. … It is important to view these trends in consideration of the fact that migration was restricted to varying degrees during the first half of the twentieth century. Geographic mobility was explicitly restricted until 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act granted free movement to those born after 1924.

Getting to where the jobs are

The importance of geographic mobility for dealing with economic adaptation and upward mobility is as relevant as ever. Companies, industries, cities, and regions will rise and fall in a dynamic, fluid economy. It’s a trade-off that comes with vibrancy. But workers need to be able to go where the jobs are. Unfortunately, geographic mobility in the US has been on the decline for over 30 years, due in part to anti-growth housing regulations that hurt housing affordability in high-wage, high-productivity regions. A 2017 analysis from the Economic Innovation Group — based in part on data from Harvard’s Equality of Opportunity Project — finds 51 percent of US counties home to 60 percent of kids exert “a negative impact on children’s future earnings.” As that report concludes, “Most children in the United States are growing up today in counties with a poor record of fostering upward mobility. As the geography of U.S. economic growth narrows, it may become even harder to prevent further retreat of economic mobility.”

I would also add that one of the most astounding findings from the recently published book Streets of Gold: America’s Untold Story of Immigrant Success — by economists Ran Abramitzky (Stanford University) and Leah Boustan (Princeton University) is that “background is not destiny.” The researchers find that “children of immigrants from nearly every country in the world are more upwardly mobile than the children of US-born residents who were raised in families with a similar income level.” Equally noteworthy is the reason why these kids are so successful. Are they especially ambitious? Do their parents hand down a superior work ethic? Well, such special attributes could be part of the story. But what’s certainly part of the story is that, as Abramitzky and Boustan write, “[I]mmigrants tend to move to locations in the United States that offer the best opportunities for upward mobility for their kids, whereas the US-born are more rooted in place.”

In economic growth as in real estate, location, location, location is key. Also: don’t forget about the Way of the Wolf.

Micro Reads

▶ Short but not sweet - JPMorgan Economics | Fed Chair Powell’s remarks at Jackson Hole were brief and hawkish. Most notably, he appeared to push back against the idea that the Fed would be easing policy next year. Instead he observed that “the historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.” He was also more candid that the cost of reducing inflation would be not only below-trend growth but also “some pain” for businesses and households. … [T]he meat of the speech was the three lessons of the Great Inflation period of the 1970s. First, inflation is the responsibility of the central bank. Even if the current bout of inflation is a global phenomenon that owes much to supply constraints, it is still the Fed’s job to constrain demand to a level more appropriate for that supply. Second, inflation expectations are important. Powell judged that current longer-run inflation expectations are well-anchored, but that a “particular risk” today is that higher inflation feeds into expectations. The third lesson is that the Fed “must keep at it until the job is done.” The “multiple failed attempts” at disinflation in the 1970s reinforced the key message of the speech, that it took a commitment to a “lengthy period” of restrictive policy to get inflation down.

▶ Nuclear fusion power inches closer to reality - Pranshu Verma, WaPo | Phil Larochelle, a partner at the venture capital firm Breakthrough Energy Ventures, said private money is flowing into fusion at such high levels because scientific advancements, such as better magnets, have made cheap nuclear fusion a likelier possibility. Going forward, Larochelle noted that getting nuclear fusion to market probably will require formal cost-sharing programs with the government, which he said could be similar to how NASA is partnering with SpaceX for space travel innovation. “In both the U.S. and the U.K., there’s now kind of new government programs and support for trying to get to a [fusion] pilot,” he said. “It’s a good kind of risk-sharing between public and private [sectors].”

▶ Warren Buffett Backs Driverless Trucks. Now They’re Real. - Thomas Black, Bloomberg Opinion | Pilot Co., which operates Pilot and Flying J travel centers and is owned by Berkshire Hathaway, agreed on Tuesday to take a stake in Kodiak Robotics Inc., a driverless truck startup. Pilot will get one of Kodiak’s five board seats. Although the investment amount and percentage of ownership in Kodiak weren’t disclosed, Pilot is now the largest strategic investor in the startup. This investment is a significant validation by Berkshire Hathaway, through Pilot, that driverless trucks are on the cusp of being a reality. It may be hard and even scary to imagine an 18-wheeler with no human on board humming down the highway intermingled with passenger cars. This may happen more quickly than people think.

▶ New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018 - David Autor, Caroline Chin, Anna M. Salomons, and Bryan Seegmiller, NBER | We find, first, that the majority of current employment is in new job specialties introduced after 1940, but the locus of new work creation has shifted—from middle-paid production and clerical occupations over 1940–1980, to high-paid professional and, secondarily, low-paid services since 1980. Second, new work emerges in response to technological innovations that complement the outputs of occupations and demand shocks that raise occupational demand; conversely, innovations that automate tasks or reduce occupational demand slow new work emergence. Third, although flows of augmentation and automation innovations are positively correlated across occupations, the former boosts occupational labor demand while the latter depresses it. Harnessing shocks to the flow of augmentation and automation innovations spurred by breakthrough innovations two decades earlier, we establish that the effects of augmentation and automation innovations on new work emergence and occupational labor demand are causal. Finally, our results suggest that the demand-eroding effects of automation innovations have intensified in the last four decades while the demand-increasing effects of augmentation innovations have not.

▶ Listening to European Electricity Traders Is Very, Very Scary - Javier Blas, Bloomberg Opinion | But the industry’s teleconference suggests the problem is broader than just rising costs. Increasingly, the words “emergency” and “shortages” are being used, with participants focusing on when, rather than if, a crisis will hit. Imagine being able to overhear conversations between Wall Street executives and the Federal Reserve as the global financial crisis unfolded in 2008.

▶ Democracies must use AI to defend open societies - John Thornhill, FT Opinion | The agonising soul-searching of scientists over building nuclear weapons resonates strongly today as researchers develop artificial intelligence systems that are increasingly adopted by the military. Excited though they are about the peaceful uses of AI, researchers know it is a dual-use general purpose technology that can have highly destructive applications. The Stop Killer Robots coalition, with more than 180 non-governmental member organisations from 66 countries, is campaigning hard to outlaw so-called lethal autonomous weapons systems, powered by AI. War in Ukraine has increased the urgency of the debate.

![50+] Stark Wallpaper on WallpaperSafari 50+] Stark Wallpaper on WallpaperSafari](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!f0jt!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F33775242-30a3-479f-8e95-9b04b529938d_1920x1080.jpeg)

What the "people to jobs" strategy for distressed places overlooks is that even if this could be achieved at a much larger scale -- which I doubt -- this strategy probably hurts those left behind, or certainly does not help.

As I reviewed in my paper on place-based policies in JEP, the empirical evidence suggests that negative population shocks of x% from a community reduce jobs in the community left behind by at least x%, so the employment to population ratio of those left behind is not improved. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.34.3.99

Beyond simply raw numbers, encouraging MORE population out-migration probably differentially removes younger and more entrepreneurial workers, which further hurts those left behind. In addition, it seriously damages the fiscal base of the already-declining community, which reduces the ability of the local community to maintain infrastructure and public services, and certainly the ability of the community to come up with new economic development strategies to attract or grow new jobs.

Flint Michigan has had a lot of out-migration. It hasn't helped those still living in Flint.

I think there's no real substitute for really thinking about "jobs to people" strategies as well as "people to jobs" strategies. "Jobs to people" will not always work, but with the right resources, many distressed communities can significantly improve employment rates and per capita earnings.