🚀 Plant more trees or go to Mars?

Why that Salesforce #TeamEarth ad with Matthew McConaughey is culture war against progress

In This Issue

Essay: Why that Salesforce ad with Matthew McConaughey is culture war against progress

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for . . . economist Glenn Hubbard on building 'bridges' versus 'walls'

Micro Reads: France bets on nuclear, life extension, the economic risks of inflation, and more . . .

Nano Reads

“But to die on Mars — to say on Mars what [Lawrence Oates] said in the wastes of Antarctica, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’ — would be in its own way a noble end, a death worth commemorating beyond the private griefs that all of us will experience and cause.” - Charles T. Rubin

💥 Important Update for My Wonderful Faster, Please! Readers and Subscribers 💥

I currently intend to start offering a paid subscription option to Faster, Please! as of February 28. While I’m still working out the exact details, accessing my twice-weekly essays and Q&A interviews with top thinkers (along with some surprises) would be included in that paid subscription, but not the freebie version. I have been writing this newsletter over the past year at night and on weekends. I hope you find it valuable.

My friends: I believe we’re at the start of an amazing period of American (and world) history — the beginning of a Great Acceleration in human progress. It’s the purpose of Faster, Please! both to document these steps/leaps forward and recommend the best ideas to make sure they happen, ASAP. You know, faster, please! I look forward to taking that journey — via economics, tech, public policy, business, history, culture, and a smidgen of politics — over the next months and years with all of you. Let’s make a better world for everyone, together. Melior mundus

Essay

⏭ Why that Salesforce ad with Matthew McConaughey is culture war against progress

Several times in this newsletter I’ve mentioned the 2020 paper “Are ‘Flows of Ideas and ‘Research Productivity in secular decline?” by economists Peter Cauwels and Didier Sornette at ETH Zurich. Short version: For decades, science has been generating fewer and fewer significant discoveries and inventions. (I go more in depth here.)

Not only is their methodology novel — they measure the number of elite scientists and technologists active in a given year — but their explanation is intuitively appealing. It just sort of feels right. Cauwels and Sornette argue that our scientific and technological stagnation is a result of tech entrepreneurs and science researchers focusing too much on incremental exploitation (innovation) as opposed to creativity (invention) and exploration (discovery).

They then highlight how stagnation is a sign that our affluent society has become extremely risk averse: “We refer to this as the zero-risk society. When wealth and age in society increases, people become ever more risk averse, focus on going concern, protection of existing wealth and rent seeking.”

That notion of the “zero-risk society” helps explain my distaste for that Salesforce ad you might’ve seen last night while watching the Super Bowl and/or during the ongoing coverage of the Winter Olympics.

Team Earth versus the metaverse and Mars

It begins with astronaut Matthew McConaughey gazing out upon the universe. “Space. The boundary of human achievement. The new frontier,” he says. But instead of venturing forth, he steers his hot air balloon back to Earth and eventually San Francisco. “It’s not time to escape. It’s time to engage. It’s time to plant more trees. It’s time to build more trust. It’s time to build more space for all of us. While the others look to the metaverse and Mars, let’s stay here and restore ours.”

This is an appalling ad for a number of reasons: First, it’s being frequently run during the Olympics, an event all about achieving your highest aspirations, not limiting them.

Second, the ad, part of Salesforce’s “Team Earth” campaign, suggests we’re playing a zero-sum game — that making a better life here on Earth necessarily means forgoing other sorts of explorations, whether into the metaverse or out into the universe. This is the kind of thinking that helps create the “zero-risk” society that Cauwels and Sornette identify. Salesforce executive Sarah Franklin has been quoted as saying we need to continue to take care of the planet, even with the “hype around going to the metaverse, Mars, space.” As if doing one prevents us from doing all of them, as noted by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen on Twitter with this meme.

There’s nothing new about criticism of space exploration

Especially in regard to that zinger directed at the space ambitions of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos (the latter of whom focuses more on the space economy than Mars colonization), the ad is trotting out a moldy criticism that’s been around since Apollo about humanity aspiring to leave this planet. Focus on poverty and injustice down here before vanity venturing out there. Leftists such as Bernie Sanders say much the same thing today, a view echoed by Salesforce.

A podcast chat I had last year with journalist Charles Fishman, author of One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission that Flew Us to the Moon, offers a corrective to that constrained view, noting, for instance, that there were three individual years of the Vietnam War, each of which cost more than the entire race to the Moon. What’s more, the Apollo Age also featured efforts to tackle poverty, women’s rights, civil rights, and voting rights in dramatic ways. Plus what’s happening today is a lot different than the Space Race. Fishman: “Musk and Bezos are in business to change the business of space, to create a space economy. . . . They want to take something that has historically cost $100 million and bring the cost down to $1 million. What used to cost $100 million to launch to space will now cost $1 million. And when you do that, as you know, you completely change what’s possible.”

Musk took on this sort of criticism during his Starship update presentation last week. He again pointed out that moving humanity off planet — such as settling Mars — serves as a “life insurance policy” against an extinction event here on Earth. “The probability of that is low, but it is not zero. . . . This is the first point in the four and a half billion year history of earth that it has been possible for humanity to save itself by venturing beyond the planet.”

Musk shifted to the “inspiring reason” for Mars colonization (as depicted in the below image from a video played during his presentation).

Life can't just be about solving problems. There have to be things that inspire you, that that move your heart, that make you glad to be [alive] when you wake up in the morning — you're excited about the future. And going out there and being a multi-planetary species and being a space-faring civilization and making science fiction not fiction forever. I think [this is] one of those things.

(Those comments remind me of the recent HBO Max series Station Eleven. It’s based on the 2014 Emily St. John Mandel novel about a Shakespearean troupe that travels around the Great Lakes region in a future America where a pandemic has killed 99.9 percent of the population. The motto of the Travelling Symphony is “Because survival is insufficient,” nicked from an episode of Star Trek: Voyager.)

Third, the ad uses McConaughey, clearly trying to riff off his role as an astronaut (see image below) in the 2014 film Interstellar, directed by Christopher Nolan — and thus acts as a de facto rebuttal to a film that makes the case for exploration, progress, and humanity “reckoning with its place in the wider universe,” to use Nolan’s words. Interstellar depicts a near-future world where a mysterious global blight is killing the planet’s vegetation, a plague that will eventually render Earth uninhabitable. Making things worse: We have turned our backs on science and reason in favor of de-growth and conspiracy theories. Cooper, played by McConaughey, is a farmer who used to be an astronaut before America gave up on space exploration and a widower because there were no longer MRI machines that could have detected the cyst in his wife’s brain. Cooper wonders why mankind has stopped striving:

We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars, now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt. We’ve always defined ourselves by the ability to overcome the impossible. And we count these moments. These moments when we dare to aim higher, to break barriers, to reach for the stars, to make the unknown known. We count these moments as our proudest achievements. But we lost all that. Or perhaps we’ve just forgotten that we are still pioneers. And we’ve barely begun. And that our greatest accomplishments cannot be behind us, because our destiny lies above us.

A pro-progress culture supports a dynamic economy

Why do these commercials matter? Why does it matter that Hollywood churns out a never-ending series of films about a civilizational collapse, whether from climate change, plague, or zombies? Why does it matter that the splashy Smithsonian Institute exhibition “Futures” is unable or unwilling to show a future of abundance and expansion?

It matters because progress is disruptive. Economic growth and technological change alter the status quo and invite reaction from incumbents. The guilds of preindustrial Europe famously played a key role in making sure Europe stayed preindustrial by blocking new technologies until governments started embracing the gains, including military ones, from the Industrial Revolution. But the benefits of disruption aren’t always obvious. A society needs a positive image of the future and faith that in the end, all the disruption will make a better world — if not for them, then for their children.

For example: Prime Movers Lab, a “deep tech” venture capital firm, recently published a road map to the future, speculating on the first commercial nuclear fusion power plant in the 2030s, near-Earth asteroid mining in the 2040s, and genetic technologies to restore lost species and ecosystems by 2050.

Back to Cauwels and Sornette, who argue that culture has a key role to play here (bold by me):

We need “to make risk-taking great again”. . . . Let us aggressively fund explorative, high-risk projects, encourage playful, creative, even apparently useless tinkering, that will surely foster serendipity in research on the longer term. . . . Why not promote the risk-taker, the explorer, the creative inventor as a new type of social influencer acclaimed like a Hollywood or sports star? Only by such a deep cultural change, by bringing back the frontier spirit and making risk-taking great again will we be able to escape from the illusionary and paralyzing zero-risk society and deal with the massive lurking risks that it produces.

Films, television, books, video games, and, yes, commercials all play a role in fighting against a drift toward the Zero-Risk Society. Unfortunately, the Salesforce ad is hardly the only commercial of late undermining that effort. During the Super Bowl, there was also an ad from electric car maker Polestar that mocked Musk’s Mars ambition. And, of course, there’s that Crypto.com “Fortune favors the brave” ad featuring actor Matt Damon walking past CGI museum exhibits about Magellan, mountain climbers, the Wright Brothers, and, finally, astronauts before ending with the stirring call to action: trade cryptocurrencies.

Is a TV commercial pushing a product also capable of inspiring an embrace of risk and disruptive progress? Of course. The Super Bowl also featured a (yet another) crypto ad with Larry David as a character who throughout history dismisses all manner of important innovations. But it’s this ad from a while back that really persuades about what a pro-progress ad is potentially capable of doing:

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for . . . economist Glenn Hubbard on building 'bridges' versus 'walls'

Glenn Hubbard is Dean Emeritus of Columbia Business School. He is also a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. From 2001 until 2003, he was chairman of the US Council of Economic Advisers. Hubbard is the author of The Wall and the Bridge: Fear and Opportunity in Disruption’s Wake, released in January. The book argues that populist politicians attempt to help the losers in a competitive capitalist world by creating walls — of both the physical and economic kinds — to insulate communities and keep competition at bay. Hubbard promotes the benefits of an open economy and creating bridges to support people in turbulent times so that they remain engaged and prepared to participate in, and reap the rewards of, a new economic landscape.

1/ Is the pandemic a pro-wall or a pro-bridge event?

I'm going to be an economist and say both. It's definitely pro-wall in the sense that we have seen some fairly arbitrary kinds of protections thrown up that have many people — I consider myself somebody who believes in science, but I’m still scratching my head at some things. On the other hand, there are amazing bridge opportunities. We've mixed up work and industries and technologies, creating enormous opportunities for people who have the skills to jump from A to B. And it's exposing that we need to help people jump more from A to B. So I'd say it's both.

2/ After the financial crisis, a question I've always asked economists is: Did that crisis change your thinking in some way? Has the pandemic changed your thinking in some way, or altered it or evolved it in any way?

Yes. I think what the pandemic has shown us is that the economy's capability to move around — whether it's the labor market, the organization of industry, how we supply goods and services — is amazingly flexible. For all of the supply chain issues that we rightly worry about today, the economy has been actually quite responsive to these very big shocks. So I think it sort of told us a little more than we might have thought about what's going on under the hood of the economy.

3/ We've had a China trade shock, and maybe we're going to have an AI or a robotic shock. I know there are already some economists who say, "Government, whether by changing tax policy or some other way, needs to nudge innovation so it is not job replacing or displacing, but job enabling." Can we really do something like that?

There's a tug of war going on right now in economics on whether robotics will on balance add to or subtract from jobs. And like all things in economics, it's complicated. It depends on the kinds of jobs. One thing policy can do is try to make sure that tax policy isn't biased one way or the other. Taxation should be neutral. But probably more constructively, putting applied research centers around the country in the way we did in the land-grant colleges might help innovations diffuse into business and job practices much more than we do today. So there are some things the government can do, but I wouldn't want to imagine too many people in Washington spending all day long trying to figure out how to organize the American economy. That might scare me.

4/ Because we're in the 2020s it's easy to wonder, "Maybe this will be a new Roaring Twenties." (Hopefully, it'll end better.) We have advances in AI and robotics, and we have CRISPR, and we have this billionaire space race. Do you think we're going to have a new Roaring Twenties and if not, what probably went wrong?

Well, I don't think Joe Biden's speaking style is the same as Calvin Coolidge's, but I do think we have the prospects for a productivity boom in the country. If you think back to the twenties, you saw the penetration of previous general-purpose technologies, like electrification, really came into their own in the 1920s, even though they weren't invented in the 1920s. We see a lot of applications as business leaders and economists that could well come to fruition. I think the issue for the twenties and the thirties in our foreseeable future is not so much whether technology can deliver, but whether politics can deliver. In other words, are we going to allow the economy to experience the productivity boom? I think it's possible. I hope so, but it's not guaranteed.

5/ During the financial crisis, there was a lot of talk about John Maynard Keynes and a lot of talk about Friedrich Hayek and their different economic views. Who is the economist for this age that we should be paying especially close attention to?

Well, I just taught political economy to the MBAs. I use Keynes and Hayek as an example of how the two men might have dealt with the pandemic. And they're probably both a little bit right. But the thinker that I use for this age is not really an economist, more of a sociologist, is Karl Polanyi. Economists talk about markets and the state, but in between is this connective tissue. And I think Smith, not the Smith of The Wealth of Nations, but the Smith of The Theory of Moral Sentiments might well have agreed with that, that we need to think more about connection and being all into the economy. So I would throw in a little bit of Polanyi.

Micro Reads

⚛ France’s Macron Bets on Nuclear Power to Fight Climate Change - Matthew Dalton, WSJ | This must have seemed an unlikely scenario after the 2011 Fukushima meltdown. But the French president want to build six new nuclear reactors “making nuclear energy the cornerstone of the country’s response to climate change. France already relies on nuclear power to generate more than 70 percent of its electricity, but the average age of its reactors is 37 years old. The piece also contain a discussion of how Frances’ reactor pause has undermined its construction expertise.

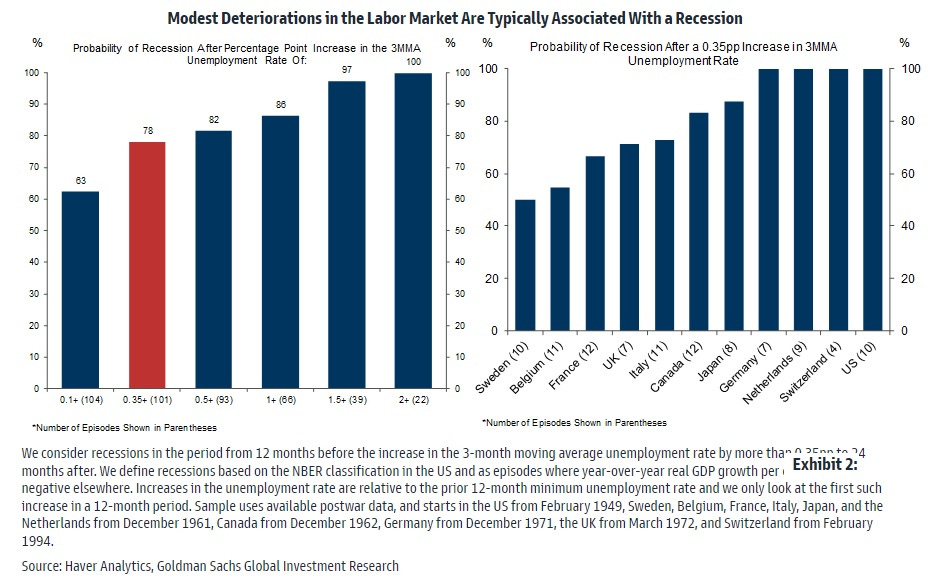

🔥 Expectations and the Fight Against Inflation - Goldman Sachs | This note highlights a monetary policy conundrum: Squashing inflation might also mean squashing the job market recovery: “The pre-pandemic 0.1–0.2 slope of the Phillips curve suggests that even a 2pp increase in the unemployment rate would only bring inflation down by 20–40bp. The challenge is that, across G10 economies, there has never been an increase in the unemployment rate by 2pp that has not been associated with a recession.” We could sure use another long, long expansion as we had after the Global Financial Crisis — but, you know, more rapid.

🧠 David Chalmers: ‘We are the gods of the virtual worlds we create’ -John Thornhill, Lunch with the FT | The co-director of New York University’s Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness and “techno-philosopher” conducts this virtual lunch in the metaverse. (Note: Eating with goggles on is apparently kind of sloppy.) He predicts that within 100 years, as the FT sums up his views, VR will be an “all immersive metaverse in which virtual and physical realities blur” and thus “the human designers of virtual worlds will assume almost divine powers.” Not too early to consider what (virtual) human rights means in the metaverse.

🧬 Does the human lifespan have a limit? - Michael Eisenstein, Nature | The UN estimates there were 573,000 centenarians alive worldwide in 2020 — more than 20 times the number 50 years earlier. It’s a stat that suggests the question of how far we can extend human life. Some researchers are optimistic, predicting a continuing upward trend. Others think we’ve reached a plateau: medical advances might allow more of us to live for 100 years or more, but a ceiling on human aging remains. Studying outlier centenarians — an endeavor complicated by the challenges of verifying identities and century-old records — has demographers hopeful about pushing that ceiling upwards despite recent stagnation in life expectancy figures caused by an uptick in premature mortality. But life scientists are skeptics of the notion that we can hold the genetic forces of aging at bay for much longer than we already have.

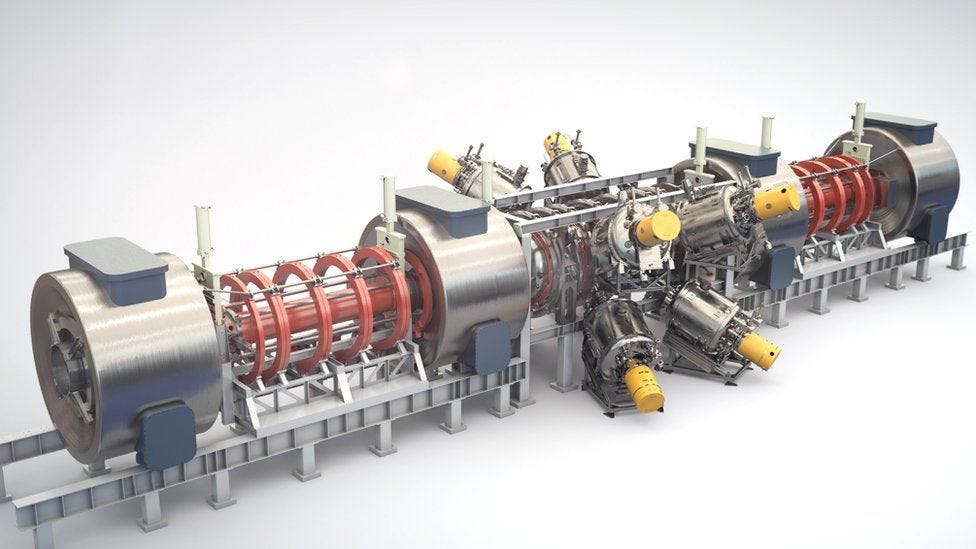

🌟 Fusion race kicked into high gear by smart tech - Paul Rincon, BBC | This is a great example of how AI-machine learning isn’t just about job-stealing automation. TAE, located near Los Angeles, has raised nearly $1 billion in private funding — more than any other fusion company. The company uses Google's expertise in machine learning for "optimising" TAE's unique fusion device. CEO Michl Binderbauer says tuning the machine when new hardware is added once took months but "we can now optimise in fractions of an afternoon.” He says Google’s help could shave a year from TAE’s schedule of building a commercial fusion test device by 2030. The piece also has an excellent explanation of TAE’s novel approach to fusion.

🌌 “Dune,” “Foundation,” and the Allure of Science Fiction that Thinks Long-Term - Jacob Kuppermann, Long Now | An insightful analysis of the long-term thinking seen in the two science fictions classics. Both of have recently received big-budget treatment by Hollywood — the former as a film, the latter a streaming service mini-series. From the piece:

Asimov and Herbert took diametrically opposed stances — the trust-the-plan humanistic optimism of Foundation in one corner, the esoteric pessimism of Dune in the other. . . . The books show up in The Manual for Civilization as well — both of them on Long Now Co-founder Stewart Brand’s list. . . . In a moment of broader cultural gloominess, Dune’s perspective may resonate more with the current movie-going public. Its themes of long-term ecological destruction, terraforming, and the specter of religious extremism seem in many ways ripped out of the headlines, while Asimov’s technocratic belief in scholarly wisdom as a shining light may be less in vogue.

🚀 Elon Musk gives hotly anticipated Starship update - Eric Berger, Ars Technica | Challenges both technical and regulatory lead Berger to conclude, after watching Musk’s presentation last week, that “Starship will make an orbital test flight in 2022. Unless it doesn't.” Musk said he thinks the FAA might as early as March give word on the environmental suitability of the Brownsville, Texas, location for orbital Starship launches. If that fails to come through, SpaceX would pivot to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Berger also notes that Musk was short on details regarding the flight-worthiness of the hardware: “Myriad other questions come to mind. For example, is the Raptor 1 engine actually powerful enough to push Starship into orbit? Or will SpaceX not attempt a launch until Raptor 2 is ready and its chambers stop melting?”

❄ Can the Winter Olympics survive on a warming planet? - Simon Willis, The Economist | The Winter Olympics keeps expanding to include more sports and events, but rapid changes in climate and surging costs in hosting the games present a challenge. The games have relied on artificial snow since 1980 in Lake Placid as it is 50 times harder, its structure is uniform and predictable, and it can last five weeks longer when temperatures are above freezing. But even today’s technology must fight against air that is too humid - and in temperatures above 28F, water won’t even freeze before hitting the ground. The current answer may lie in recycled snow kept in snow banks or wrapping snow during warmer months with insulated coverings.

Nano Reads

▶ Starship Update - Elon Musk, SpaceX |

▶ Can Nuclear Power Go Local? - Jessica Lovering and Suzanne Hobbs Baker, Issues in Science and Technology |

▶ Hypersonic Weapons Can’t Hide from New Eyes in Space - Jason Sherman, Scientific American |

▶ European fast grocery hits speed bump with Dutch halt on new 'dark stores' - Toby Sterling, Reuters |

▶ Earth-like planet spotted orbiting Sun’s closest star - Davide Castelvecchi, Nature |

▶ The Nuclear Industry Argues Regulators Don’t Understand New Small Reactors - Daniel Moore, Bloomberg Businessweek |

▶ Faster Internet displaces social capital in the UK - Andrea Geraci, Mattia Nardotto, Tommaso Reggiani, Fabio Sabatini, VoxEU |

▶ The power of stars to meet our energy needs? This is something to be excited about - Arthur Turrell, The Guardian

Great read today. Thank you, love the insights and I think we've all been dragged down by pessimism. There is still so much to be hopeful for, and so much we can do to make things better!