🔥 I’m worried about inflation. And it has nothing to do with politics or Joe Biden.

Also: Five Quick Questions for . . . innovation expert Matt Ridley

“In the 21st century, we should come very close to eliminating most disease, most ignorance, most poverty, and most of the grinding isolation that human communities have always lived with. . . . Whatever that future society chooses to do, it [will have] the kinds of opportunities that no group has ever had before. Clearly we are — and should be — willing to work for this.” - Herman Kahn, The Coming Boom, 1983

In This Issue

Long Read: I’m worried about inflation. And it has nothing to do with Joe Biden.

5QQ: Five Quick Questions for . . . innovation expert Matt Ridley

Short Read: Why I consider Station Eleven pro-progress fiction

Micro Reads: mRNA and MS;

Long Read

🔥 I’m worried about inflation. And it has nothing to do with politics or Joe Biden.

Nobel laureate economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman recently conceded that he had underestimated the persistence of the current inflation surge. But it was this bit that really caught my attention: “Inflation is an emotional subject. No other topic I write about generates as much hate mail. And debate over the current inflation is especially fraught because assessments of the economy have become incredibly partisan and we are in general living in a post-truth political environment.”

Now I’ve been an inflation worrier — but my concern has nothing to do with how rising prices affect public perception of Bidenomics or the upcoming midterm elections or 2024 or whatever. My concern has been and continues to be this: Spiking and sustained inflation could lead to Federal Reserve actions, both interest rate hikes and a reduction of the bank’s nearly $9 trillion portfolio of Treasury and mortgage securities, that not only cool off prices but trigger a recession. As the below chart shows, Fed tightenings and economic downturns tend to go hand in hand. (Note: The chart does not include the recent pandemic-induced recession.)

And it’s not just that recessions are bad for workers, it’s that long expansions are really, really good — even the ones that are unspectacular in terms of GDP growth. We should want to the good times to roll on for as long as possible. For example: The post-Global Financial Crisis recovery and expansion was steady but slow. Yet it eventually produced impressive results. This from The Recovery From The Great Recession: A Long, Evolving Expansion by Jay C. Shambaugh (George Washington University) and Michael R. Strain (my colleague at the American Enterprise Institute):

In fact, the business cycle (including recession and recovery) beginning in December 2007 was one of the better periods of real wage growth in many decades, with the bulk of its gains coming in the last years of the recovery. . . . By 2015, prime-age labor force participation began to increase. In the last five years of the expansion, wage growth had picked up at the bottom of the income distribution, outpacing gains in the middle and at the top of the distribution. Employment rates for the workers with the least education rose further above their pre-recession level than those for college graduates. Vulnerable workers saw their labor market prospects improve considerably. The length of the expansion — which allowed the labor market to tighten — was critical to both bringing people back into the workforce and seeing wage gains pushed across the income distribution. Had the recovery ended earlier, those benefits would not have materialized. The final years of the recovery indicate that tight labor markets are the most effective jobs and wages program in the government’s policy arsenal. In addition, conventional measures of income inequality show that its growth has stagnated or even declined since the Great Recession began.

The below chart from that paper shows just how broad and robust the wage gains eventually became:

Then there’s this: Long expansions where everybody is prospering are potent antidotes to the drawbridge-up populism of the left and the right. (A 2019 Reuters analysis found that real GDP growth in the 2600 counties won by Trump barely topped 1 percent vs. 1.8 percent in the counties carried by Hillary Clinton.) Had the post-crisis expansion continued without the pandemic pause, I believe we would be hearing far less these days about “late capitalism,” “all billionaires are a policy error” (even the ones creating the space economy), and the need to mimic China’s top-down industrial-planning strategy.

Economic stagnation and volatility combined with pessimism about the value of economic growth and tech progress (which then gets reflected in public investment and regulation) can create a destructive, self-fulfilling doom-loop. At least that’s one way to read the 1970s productivity and progress downturn.

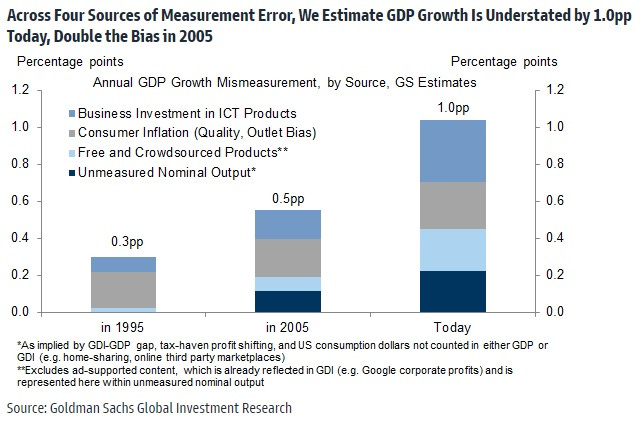

There’s one other connection to make when thinking about inflation and progress. Improving the economy’s long-term productivity by strengthening its supply side helps create a more inflation-resistant overall economy. Wall Street banks such as Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan have been trying to figure out to what extent current government statistics are befuddled by the digital economy and thus underestimate productivity growth/ real GDP growth and overestimate inflation. In a 2019 analysis, for instance, GS estimated that the pace of annual real GDP growth is understated by around 1.0pp of GDP, up from 0.5pp in 2005 and 0.3pp in 1995 due to various mismeasurement issues.

In other words, there are lots of good reasons for pro-progress types, such as myself and many of you readers, to consider what’s happening with price inflation that has nothing to do with the partisan politics of the moment.

5QQ

❓ Five Quick Questions for . . . innovation expert Matt Ridley

Matt Ridley is an award-winning and bestselling author of numerous books, including How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom and The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves. From 2013 to 2021, Matt sat in the House of Lords. His latest book, co-authored with Alina Chan, is Viral: The Search for the Origin of COVID-19.

1/ Do you think the pandemic has made the US and UK more willing to embrace new technological solutions (operation warp speed in the US and vaccines) or more risk averse?

It has briefly made both the UK and US willing to do things at speed, in parallel and with urgency, to bring in new technologies, but only in a few areas, and there are signs of government returning to old, slow ways.

2/ What economic view or opinion of yours has been changed/altered by the pandemic?

The value of working from home.

3/ What is the most worrisome anti-growth factor out there?

Anti-innovation thinking, whether it comes from vested interests, sluggish bureaucrats or superstitious fearmongers.

4 / What is a pro-growth economic policy that deserves more attention? Or is helping workers deal with disruption a more important public policy goal right now?

Reducing the time bureaucrats take to regulate. It's not that they say no, it's that they take too long to say yes.

5/ What would you say to some who stated that “billionaires are a policy error” or “billionaires shouldn’t exist”?

Why are they worse than trillion dollar governments with monopolies on the technologies of violence?

(Want more? Check out my lengthy podcast chat (audio and transcript) back in June 2020 with Ridley.)

Short Read

📺 Why I consider the dystopian Station Eleven to be pro-progress fiction

I finally binged my way through Station Eleven, the HBOMax series based on the 2014 post-apocalyptic novel by Canadian writer Emily St. John Mandel. The mini-series and book both tell the story of the Travelling Symphony, a Shakespearean troupe touring the Great Lakes region some twenty years after a superflu pandemic killed between 99 percent and 99.9 percent of the world’s population (The group’s motto: “Because survival is insufficient.”) Much like Lost was famous for doing, Station Eleven shows the lives of the characters both past and present. And it’s those poignant flashbacks, which emphasize how much has been lost — indeed, one survivor creates a Museum of Civilization in an airport traffic control tower filled with all manner of 21st century gadgets — that are particularly moving, even heartbreaking.

Anyway, the series’ conclusion prompted me to start re-reading Station Eleven the book, which I first read when it was originally published. I had forgotten about chapter six, just a page and a half. It packs quite the punch:

AN INCOMPLETE LIST: No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below. No more ball games played out under floodlights. No more porch lights with moths fluttering on summer nights. No more trains running under the surface of cities on the dazzling power of the electric third rail. No more cities. No more films, except rarely, except with a generator drowning out half the dialogue, and only then for the first little while until the fuel for the generators ran out, because automobile gas goes stale after two or three years. Aviation gas lasts longer, but it was difficult to come by.

No more screens shining in the half-light as people raise their phones above the crowd to take photographs of concert stages. No more concert stages lit by candy-colored halogens, no more electronica, punk, electric guitars.

No more pharmaceuticals. No more certainty of surviving a scratch on one’s hand, a cut on a finger while chopping vegetables for dinner, a dog bite.

No more flight. No more towns glimpsed from the sky through airplane windows, points of glimmering light; no more looking down from thirty thousand feet and imagining the lives lit up by those lights at that moment. No more airplanes, no more requests to put your tray table in its upright and locked position — but no, this wasn’t true, there were still airplanes here and there. They stood dormant on runways and in hangars. They collected snow on their wings. In the cold months, they were ideal for food storage. In summer the ones near orchards were filled with trays of fruit that dehydrated in the heat. Teenagers snuck into them to have sex. Rust blossomed and streaked.

No more countries, all borders unmanned. No more fire departments, no more police. No more road maintenance or garbage pickup. No more spacecraft rising up from Cape Canaveral, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, from Vandenburg, Plesetsk, Tanegashima, burning paths through the atmosphere into space.

No more Internet. No more social media, no more scrolling through litanies of dreams and nervous hopes and photographs of lunches, cries for help and expressions of contentment and relationship-status updates with heart icons whole or broken, plans to meet up later, pleas, complaints, desires, pictures of babies dressed as bears or peppers for Halloween. No more reading and commenting on the lives of others, and in so doing, feeling slightly less alone in the room. No more avatars.

That “incomplete list” of what had been lost due to civilizational collapse made me think about the work and writings of Deirdre Nansen McCloskey, professor of Economics, History, English, and Communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago. There may be no more compelling explainer and evangelist for the wonder-worker power of innovation-driven, market capitalism than McCloskey. Not that McCloskey is a fan of the word “capitalism.” As she sees it, a more accurate description of the world’s dominant socioeconomic system would be “technological and institutional betterment at a frenetic pace, tested by unforced exchange among all the parties involved.” Or perhaps “fantastically successful liberalism, in the old European sense, applied to trade and politics, as it was applied also to science and music and painting and literature.” But maybe settle on “trade-tested progress” or simply “innovism.”

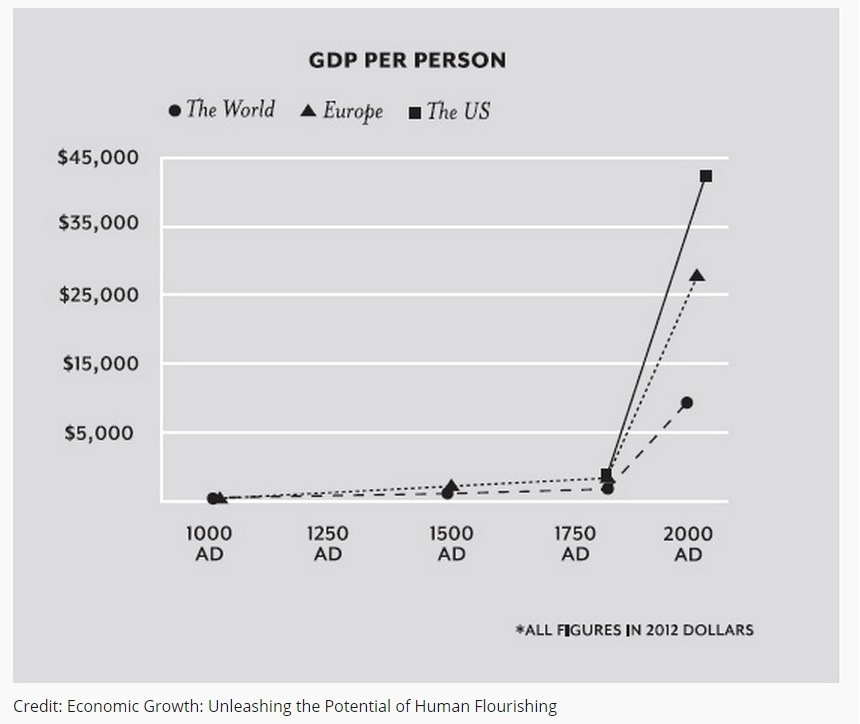

Why is McCloskey such an “innovism” enthusiast? First, a chart — and then her inimitable explanation:

Many humans, in short, are now stunningly better off than their ancestors were in 1800. . . . [The] much-maligned “capitalism” has raised the real income per person of the poorest since 1800 not by 10 percent or 100 percent, but by over 3,000 percent. Cheap food. Big apartments. Literacy. Antibiotics. Airplanes. The Pill. University education. The increase is a factor of thirty. That is, 30 minus the original, miserable, base of 1.0, all divided by the base is 29/1, to be multiplied by 100 to express it per hundred — or a 2,900 percent increase over the base, 3,000 near enough.

What I like about that quote is that it doesn’t just give the numbers, as miraculous as they are. McCloskey also reminds us specifically of what economic growth and technological progress — the forces that have created the modern world — have provided humanity, much as Mandel does in Station Eleven chapter.

But growth and progress don’t just give us a world worth living in, a world worth protecting. It gives us powerful means of protecting it, whether mRNA supervaccines, asteroid deflection technology, or climate engineering techniques. So for me, Station Eleven, although it’s a dystopian drama, has a tech-solutionist silver lining that encourages me to keep pushing this project.

Micro Reads

🦠 Common Virus May Play Role in Debilitating Neurological Illness - Gina Kolata, NYT | “For decades, researchers have suspected that people infected with an exceedingly common virus, Epstein-Barr, might be more likely to develop multiple sclerosis, a neurological illness that affects a million people in the United States. Now, a team of researchers reports what some say is the most compelling evidence yet of a strong link between the two diseases. . . . While it remains to be seen whether the finding will result in treatments or cures for multiple sclerosis, the study may further motivate research into therapies and vaccines for the condition.” What makes this finding even more exciting is that Moderna, maker of one of the mRNA Covid vaccines, just started an early trial of an mRNA vaccine against Epstein-Barr.

🗺 A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems - Derek Thompson, The Atlantic | From rapid tests to masks to supply chain interruptions, scarcity seems to be the new norm in the United States as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. But America's scarcity problem is bigger than the pandemic, and the antidote to our scarcity woes is an abundance agenda of clean energy investment, infrastructure build up, deregulation, and an emphasis on productivity and economic growth. Thompson: “This is an unabashedly utopian vision. But moving from venting to inventing, from zero-sum skirmishes over status to positive-sum solutions for American greatness, requires not just a laundry list of marginal improvements but also a defense of progress and growth.”

🧠 A narrowing of AI research? - Joel Klinger, Juan Mateos-Garcia, Konstantinos Stathoulopoulos, Cornell University | Deep learning enables artificial intelligence to take advantage of massive datasets by extrapolating patterns to improve AI performance. But has the success of deep learning crowded out other research avenues, narrowing the field of AI exploration? A review of AI research suggests that "diversity in AI research has stagnated in recent years, and that AI research involving the private sector tends to be less diverse and more influential than research in academia," which highlights the need for federally funded, basic scientific research into artificial intelligence.

🛋 Reddit ‘antiwork’ forum booms as millions of Americans quit jobs - Taylor Nicole Rogers, FT | On Reddit, one of the internet's most-visited websites, more than a million Americans have joined the r/antiwork forum to discuss their exhaustion with the US labor market, post screenshots of resignation letters, and share stories of their former bosses. Members of the antiwork movement "largely believe that people should strive to work as little as possible and preferably for themselves. Many who have stopped working say they operate their own microbusinesses." While it's difficult to say how widespread antiwork beliefs have become, the movement's popularity has coincided with labor force participation rates that have employers complaining about a shortage of workers.

⏩ Progress, humanism, agency - Jason Crawford, Roots of Progress | Crawford (interviewed in my previous Faster, Please! issue) argues that a progress movement for the 21st century relies on a three-legged stool of ideas: progress as a historical fact, humanism as the standard of value, and a belief in human agency. Progress advocates should begin by spreading the good news that material living standards have improved by leaps and bounds in the past two centuries alongside unprecedented advances in scientific and technological knowledge. And the guiding principle going forward will eschew a romantic clinging to the past in favor of the pursuit of those things which help us live better, longer lives with more opportunities to flourish. To get there, we'll have to remember that continued progress is possible — but it's up to us to choose it.

⚛ Why is the Nuclear Power Industry Stagnant? - Austin Vernon | In a previous issue of Faster, Please! I explored why France generates more than two-thirds of its electricity with nuclear while the US only generates about a fifth of its electricity with nuclear. Cost is another important factor: Because nuclear operating costs are largely fixed and higher than those in natural gas or coal-fired facilities, "traditional, depreciated nuclear power plants barely break even with a lighter regulatory burden." With declining costs in solar and wind, nuclear just isn't competitive anymore. And while investment in new nuclear technologies — including fusion! — might pay off, "there is a good chance nuclear does not have a true revival until we miniaturize it." Vernon gives a good overview of where that technology currently stands.

🚁 Joby’s CEO Wants to Make Flying Taxis as Cheap as Yellow Cabs -Bloomberg Businessweek | “This year, Joby’s manufacturing line will start cranking out five-seat aircraft (initially, there will be a pilot) and putting them through the paces for certification from the Federal Aviation Administration. Thanks in part to its purchase of Uber Technologies Inc.’s flying car unit, Joby has leases lined up for strategic rooftops — soon-to-be sky ports — in major cities. Its plan is to quickly shuttle a person from the airport to, say, an urban transportation hub.”