🚀 Faster, Please! Week in Review+ #10

Disney's 'Tomorrowland Problem;' What 'Moneyball' got wrong; the value of abundant energy; 5 Quick Questions for 'vetocracy' expert Will Rinehart and economist Alex Tabarrok

My free and paid Faster, Please! subscribers: Welcome to Week in Review+. No paywall! Thank you all for your support! For my free subscribers, please become a paying subscriber today. (Expense a corporate subscription perhaps?)

Oodles of Substack goodness this week. Just a crazy amount, as you will see below. I covered a wide range of subjects in the essays, Q&As, and micro reads on Monday and Thursday (or sometimes Friday), as well as a paywall-free issue on Wednesday. Enjoy the summaries, recaps, as well as a bit of new content (usually)!

Melior Mundus

In This Issue

Essay Highlights:

— The story of Disney's 'Tomorrowland Problem' and America's Long Stagnation (May, 2 2022)

— What “Moneyball” got wrong: Pro baseball scouts can teach us a lot about automation and technological unemployment (May 4, 2022)

— What if America had cheap, clean, unlimited energy? (May 6, 2022)

Best of 5 Quick Questions:

— Policy analyst Will Rinehart on America’s “vetocracy” problem

— Economist Alex Tabarrok on the American Way of innovation

Essay Highlights

🐭 The story of Disney's 'Tomorrowland Problem' and America's Long Stagnation | When Disneyland had its grand opening on July 17, 1955, Tomorrowland’s most eye-catching attraction was the Moonliner, a nearly 80-feet-tall gleaming white rocket ship made of shiny aluminum. The Moonliner hosted the “Rocket to the Moon” attraction meant to simulate what a lunar journey might be like in 1986.

Long before the far-off year, however, Disneyland imagineers discovered they had an issue with Tomorrowland’s ability to successfully fulfill Walt Disney’s ambitious vision for it. By the mid-1960s, with the Apollo program in full swing, Tomorrowland seemed dated and more like, in Walt’s own words, “Yesterdayland.” Disneyland had a “Tomorrowland Problem.” Soon after, the end of Apollo and the start of the Great Downshift in US productivity growth meant Tomorrowland could no longer feed off the innovations and pro-progress optimism of the world around it.

But there’s some good news coming from the House of Mouse, news that nicely syncs with my hopes for a New Roaring Twenties, followed by a Thrilling Thirties. Last September saw the opening of Space 220, a theme restaurant at Walt Disney World’s Epcot. The attraction attempts to create an immersive space experience for guests via a simulated journey to Centauri Space Station in Earth orbit. I hope it is a harbinger of American culture producing more expansive Up Wing visions.

⚾ What “Moneyball” got wrong: Pro baseball scouts can teach us a lot about automation and technological unemployment | When you consider automation’s impact on jobs, perhaps you think about long-haul truck drivers and self-driving 18-wheelers. But I think about pro baseball scouts. Perhaps the most memorable scene in the 2011 baseball film Moneyball is when Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane (played by Brad Pitt) — trying to install a more data-driven approach to player evaluation — holds a meeting with his old-school scouting department.

A Moneyball approach to player scouting and team managing has yet to lead to a World Series win or even a championship appearance for Beane and the notoriously cheapskate A’s. But it did for the Houston Astros. They won the World Series in 2017 and were noted for their data analytics (and later for their cheating). The Astros also fielded a large scouting department, which they cut by two-thirds after that championship. The team decided to go full Moneyball.

But in 2020, the Astros changed their mind. The team started expanding the scouting department. The new general manager explained the decision this way:

Our scouts have shown an amazing ability to use that information and take it into their reports and their assessment of the player, and so in some sense what we want them to do is help us interpret a lot of that information that we get from the new technologies. But at the same time we don’t have technology that can figure out what is in a kid’s work ethic (or) what is in his makeup. Is this the kind of kid who gets out there to the low minors and can work his way through it, grind his way through?

A trained economist couldn’t have better described the process of technology complementing labor rather than merely replacing it. Thinking about how a machine or robot can replace workers is simpler than imagining how technology can make workers more productive or even create new things for workers to do — with the result being higher wages and more jobs. It’s probably why so many of us fear the job impacts of new tech despite a long history of such fears failing to materialize.

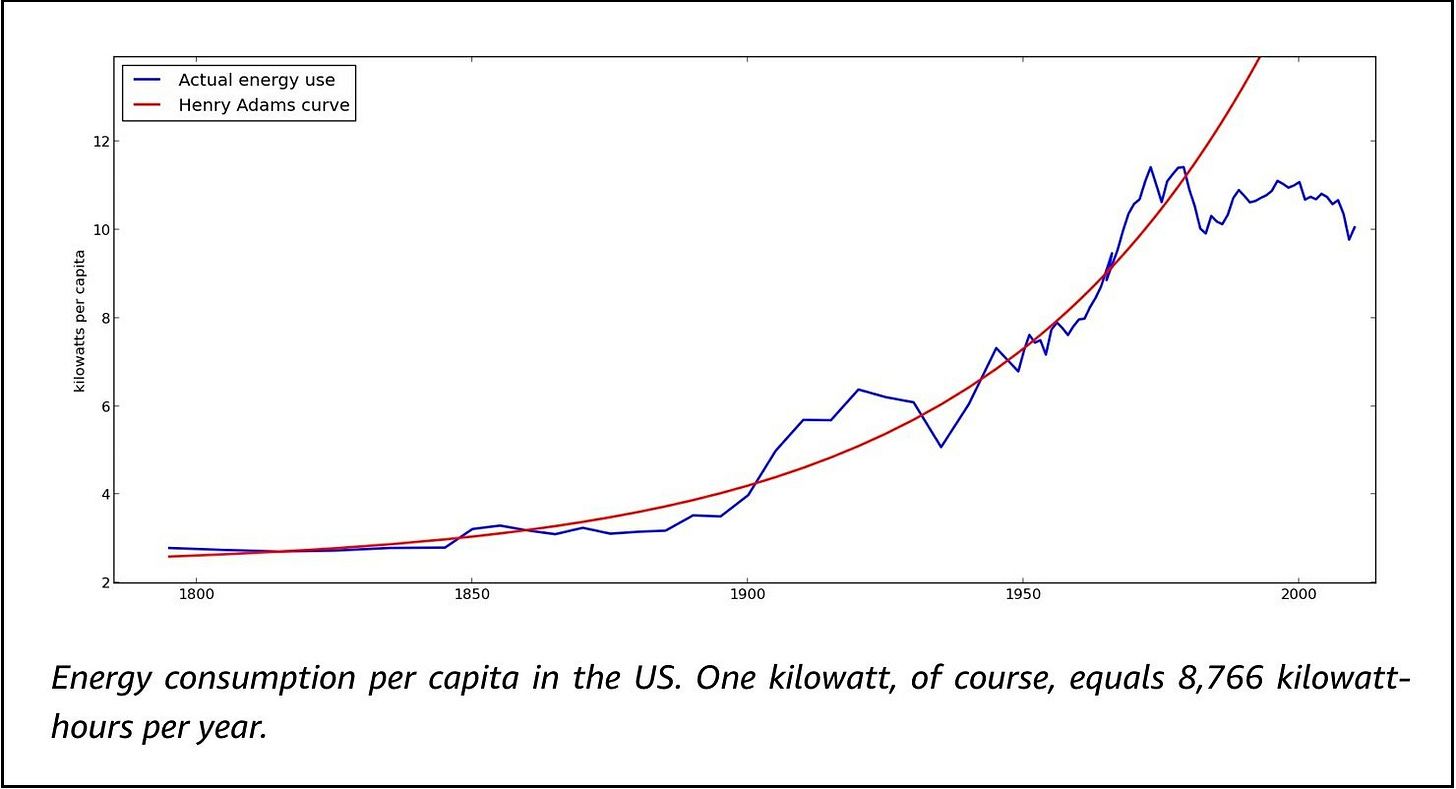

⚡ What if America had cheap, clean, unlimited energy? | The chart below tells a story of plateauing per capita energy use in the early 1970s. It comes from Where Is My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall.

It’s Hall’s contention that a lack of energy intensity (and technical progress in energy) is a big reason why many techno-optimist forecasts from the 1960s failed to happen. We learned to do more with less energy when we should have been doing more — much more — with more energy. But does the upward-sloping red line of the Henry Adams Curve lead to a high-energy utopia of nuclear-powered flying cars among marvels so far seen only in sci-fi?

I wouldn’t go that far. Yes, energy — how it is generated and how it is used — is tremendously important. But we shouldn’t overemphasize what that deviation from Henry Adams Curve has meant to the US economy and society. Many of those unfulfilled postwar dreams can’t easily be blamed on a retreat from energy abundance. I’m not sure how stalled energy intensity directly explains why we aren’t already living to 120, regrowing limbs, downloading new skills via direct brain-computer interface, or vacationing on the Moon or Mars.

Yet I also don’t want to underestimate the importance of cheap, unlimited, carbon-free energy. Not at all. It’s certainly worthwhile to have an innovation ecosystem — including regulation and R&D — that’s friendly to progress in nuclear fission/fusion, geothermal, or even space solar. As a 2015 Physics Today commentary on energy abundance points out:

Processes that currently consume too much energy to be cost-efficient could become widespread and beneficial. For example, the desalination of seawater would relieve Earth's water shortages. Trash could be recycled on a massive scale to extract valuable trace elements, such as rare earths. Carbon dioxide could be sucked out of the atmosphere to mitigate climate change. People could live comfortably in Earth's polar regions.

People sometimes ask, such as on social media, “What is the point of progress?” But, when you think about it, what is the point of that question? A (far) higher-energy planet, enabled by tech progress, seems likely to be an obviously better one.

Best of 5 Quick Questions

Will Rinehart is a senior research fellow at the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, where he specializes in telecommunication, Internet, and data policy, with a focus on emerging technologies and innovation. Lately, he has been cataloging "an ongoing list of the ways in which excessive veto points have slowed development, transportation projects, housing, and people just trying to start a business." That project, along with Will's recent blog post, "The costs of CEQA" caught my attention.

There are a number of theories about why government can't seem to get things done even when there is broad bipartisan agreement: a patch-work quilt of policy kludges, ossified regulatory institutions, administrative sludge, etc. What is "vetocracy" and how does it fit into this literature?

Though vetocracy is still an undertheorized idea, I see it as a distinct idea from red tape and other kinds of regulation. To be fair, vetocracy is like all the others in that it acts as a bottleneck. But red tape, regulation, and administrative sludge all prohibit conduct.

Vetocracy isn’t the regulation of conduct. Vetocracy describes a system characterized by excessive vetoes. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama coined the term, and while I am not wedded to it, it highlights a new tendency of political institutions. It takes longer to build because the process can be overrun by vetoes. Too many actors have veto rights over what gets built. Vetocracies have popped up in forest management, housing, [affordable housing projects], housing the homeless, interstate construction, wireless Internet deployment, wired Internet deployment, expanding the number of hospital beds, and so on.

Alex Tabarrok is the Bartley J. Madden Chair in Economics at the Mercatus Center and a professor of economics at George Mason University. He and Tyler Cowen founded Marginal Revolution, where Alex blogs about innovation, economic growth, and other topics of interest to Faster, Please! readers. Throughout the pandemic, Alex has been writing insightfully about vaccines, technological advancement, and pro-progress culture.

What do you make of the argument that China's recent industrial success, particularly in tech, points to a more viable industrial strategy than America's current approach?

Every generation launches a new competitor to America and the people who don't like capitalism and America's individualist, free market economy trumpet that now the American way is being left in the dust. In the progressive era it was the Germans (how did that work out?), then it was the Russians (remember Sputnik?), then it was the Japanese (buying up Rockefeller center! the horror!), then it was the Chinese (look at those high speed rail lines!). My message to Americans is to double down on America. Double down on immigration, entrepreneurship, innovation, building for tomorrow, free markets, free speech and individualism and America will take all new competitors as it has taken all comers in the past. The world should be more like America not the other way around.