📈 You say 'budget deficit,' I say 'productivity deficit'

Boosting US economic growth would help put America on a better fiscal path

Quote of the Issue

“The future always comes too fast and in the wrong order.” - Alvin Toffler

The Essay

📈 You say 'budget deficit,' I say 'productivity deficit'

One upside from the ongoing conflict in Congress about raising the US debt ceiling (it should be raised then eliminated, by the way) is that Washington is again thinking about debt and deficits — and what to do about them. My hope is that policymakers won’t wait for a nasty financial market reaction before reforming both the long-term drivers of debt and the federal tax code.

Of course, economic history suggests an economy generating faster economic growth and more tax revenue would be helpful in this effort. Let us for a moment return to the halcyon days of the second half of the 1990s. Just as everyone was giving up on the notion of rapid growth, the American economy started to grow rapidly. From 1995 through 2000, real US GDP grew at a blistering average annual pace of 4.3 percent, helping boost federal revenue as a share of GDP to nearly 20 percent, the highest peacetime level ever. That surge in revenue in turn helped lower the US publicly-held debt-to-GDP ratio from 48 percent in 1994 to 31 percent in 2001. Part of that decline: budget surpluses from 1998 through 2000.

In the 2001 Economic Report of the President, President Bill Clinton highlighted fiscal responsibility as a key factor in the economic boom:

Our strategy has been based, first and foremost, on a commitment to fiscal discipline. By first cutting and then eliminating the deficit, we have helped to create a virtuous cycle of lower interest rates, greater investment, more jobs, higher productivity, and higher wages. In the process we have gone from the largest deficits in history to the largest surpluses in history. We have extended the life of the Medicare trust fund to 2025—when I was elected President, it was scheduled to go bankrupt in 1999. And we have paid off $362.5 billion in debt.

That said, the America’s fiscal situation also fortuitously benefitted from an economy gaining a new technology that helped it better use an existing technology. As economist Robert Gordon observes in The Rise and Fall of American Growth:

The late 1990s, when [total factor productivity] growth finally revived, witnessed the marriage of computers and communication. Suddenly within the brief half-decade interval between 1993 and 1998, the standalone computer was linked to the outside world through the Internet, and by the end of the 1990s, web browsers, web surfing, and e-mail had become universal. The market for Internet services exploded, and by 2004, most of today’s Internet giants had been founded.

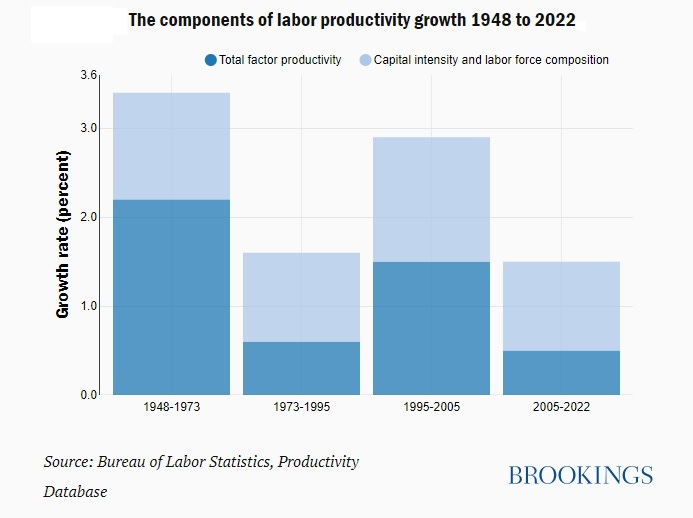

Total factor productivity, a measure of the impact of technology, was a key factor in the 1990s productivity boom (which extended through 2005) and thus the overall economic boom.

I think you see where I’m headed here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.