💥 Will AI cause 'explosive' economic growth?

5 Quick Questions for … policy writer Aaron Renn on what we can learn from Indianapolis

Quote of the Issue

“Terror via technical surprise is the greatest threat to the survival of the human race.” - Vernor Vinge, Rainbows End

The Essay

💥 Will AI cause “explosive” economic growth?

The flipside of artificial intelligence causing existential human risk is AI generating explosive economic growth. Both scenarios, so far, are purely science fictional. But that hasn’t prevented considerable discussion about the potential threat of the former.

There’s been far less analysis of the latter — which, I think, says something unfortunate about societal attitudes about technology and risk. A prime mission of this newsletter is to shift such Down Wing attitudes, at least in some small way. So I’ve been writing a lot about the potential benefits of AI/machine learning, including the recent advances in generative AI. One potential benefit: much faster productivity and economic growth.

How much faster? Maybe explosively faster. Much faster than has ever been experienced? Fingers crossed.

The possibility of AI generating warp-speed economic growth was the subject of a fascinating recent conversation, published at the wonderful Asterisk magazine, between Open Philanthropy economist Matt Clancy and Tamay Besiroglu, a research scientist at MIT’s Computer Science and AI Laboratory.

First, some definitional housekeeping. By “explosive growth,” Besiroglu and Clancy are describing him a rate of growth, in Besiroglu’s words, “that far surpasses anything we’ve previously witnessed — a minimum of tenfold the annual growth rate observed over the past century, sustained for at least a decade.”

The optimistic Besiroglu assigns a 65 percent chance of explosive growth from AI of the sort that can do much if not all of what humans currently do — artificial general intelligence or something close to it — while the more cautious Clancy gives a 10 percent to 20 percent change of explosive growth “with most of that probability clustered around the low end” once AI is fully deployed through the economy. Some nice framing here from Clancy:

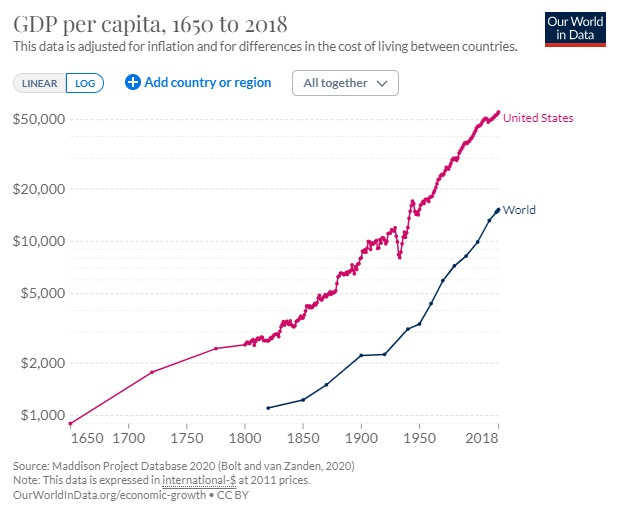

“Explosive” is certainly an apt term for what we’re talking about. GDP per capita grew at roughly 2% per year over the 20th century, so if we jump to 20% per year for 10 years, that’s about 90 years of technological progress (at 2% per year) compressed into a decade. Ninety years of progress was enough to go from covered wagons to rocket ships! And your definition also encompasses even faster growth persisting for even longer!

Looking forward, the Congressional Budget Office is expecting real GDP per person to average 1.3 percent over the next three decades (1.3 percent labor productivity, 0.3 percent labor force growth), 0.3 percent less than the average growth of 1.6 percent over the past three decades.

Here’s how Besiroglu and Clancy address some key issues with the notion of explosive growth far beyond US history and those CBO forecasts (and again I recommend reading the original piece in all its glorious detail):

➡ Is there historical precedent for explosive growth?

Besiroglu points out that economic growth has been much faster since the start of the Industrial Revolution than before, and we’ve seen some extremely high rates of “catch-up” growth in East Asia: China, Singapore, South Korea. There’s enough precedent, he writes, to make assessing the prospects for explosive growth a worthwhile pursuit, even given the speculative nature at this point of AI development and its economic impact.

Clancy points out that while AI might have an explosive growth impact, an influx of important general-purpose technologies, or GPTs, since the last 19th century — electrification, industrial chemical production, and the computer-internet combo — have transformed the material world we live in without shaking US growth rates from that steady 2 percent pace.

➡ What does basic economics say about the possibility of explosive growth?

Besirgolu explains that the production of ideas plays a key in economic growth and differs from other factors of production, capital and labor, as their availability doesn’t diminish with increased use. More people means more idea generators, “enhancing productivity and creating a loop of continuously accelerating growth.” And while global population growth has slowed, the addition of AI as a new idea generator and researcher means “our population of workers and idea producers could once again grow exponentially.”

Clancy observes that there are a huge number of critical and different tasks required to generate innovation. If AI can automate lots of these tasks, the pace of innovation could accelerate. But there's a hitch: Even if AI could do half the innovation tasks at lightning speed, innovation wouldn’t necessarily speed up because the remaining tasks would still be done by humans. Of course, if you could retrain the displaced workers to do the remaining tasks, those tasks would get done in half the time, speeding up progress overall. But history shows task automation happens quite gradually: “During the 20th century we automated a great deal of stuff that previously only humans could do, and humans had to continually shift the nature of their work. And yet, through that whole period, growth didn’t accelerate.”

➡ How important are human labor “bottlenecks” to the case for and against explosive growth?

Besiroglu thinks the bottleneck argument only works if lots of tasks, at least 25 percent, can’t be done by AI or “digital workers.” Even so, economic output might still increase by “one or two orders of magnitude” due to the complementary nature of tasks: The outputs of automated tasks are more valuable when combined with the outputs of non-automated tasks. As AI automation increases — and he thinks it won’t be a long, drawn-out process — the value of already-automated tasks grows, leading to a compounding effect that substantially boosts growth. What’s more the problem of bottlenecks, and the value of eliminating them, will draw lots of investor attention to eliminating them

Clancy observes that automation has been taking place for a long time, such as the replacement of dockworkers by automation or the use of industrial robots on assembly lines. Despite these advancements, economic growth has remained steady: “I’m not sure why it should be so different when it is cognitive work that is being handed off to the machines.” Even though a) automation has been an ongoing process in the US economy, and b) the US economy has grown much bigger and thus also the incentives for automation, it has not c) resulted in explosive growth. Just the more-or-less same pace of steady growth.

➡ Are we underestimating the pace of AI automation from digital workers?

Besiroglu points out that while explosive growth most likely requires rapidly accelerating or full automation, AI has the potential to do just that, unlike other GPTs. What’s more, the compute required to train AI models is increasing rapidly: “Given compute trends, we will likely have enough compute to automate 90 percent of tasks no more than a few decades after we will have enough compute to automate the first 20 percent.”

Clancy suggests several constraints to automation beyond AI capabilities: Many tasks require physical capabilities, and robotics may not develop as quickly as AI. Human involvement is likely to be seen as desired and essential in lots of activities, such as live performances in entertainment or in-person education. Regulatory progress also might not be as fast as technological progress, even if it eventually gets to where it needs to be. Then there’s the issue of time: You can only compress time so much, whether it’s watching movies, running an experiment, or growing crops.

➡ Are we underestimating the constraints on AI automation?

Besiroglu thinks the huge potential of AI will go a long way to creating incentives to rapidly create a pro-progress regulatory structure. And time might be more flexible that one might think. AI could allow experiments to be run more quickly: “Rather than launching one rocket design, observing it blow up, going back to the drawing board, and launching the next design the following year, tens or hundreds of rockets could be launched basically simultaneously.”

Clancy counters that many of Besiroglu’s arguments really depend on AI being quite powerful, and obviously so. If it isn’t, then, for instance, the incentives for rapid regulatory reform won’t be nearly as powerful: “Can advanced AI learn a lot from parallel experiments? Can it find massive efficiencies in how we design experiments? Can it skip experiments by running sufficiently detailed simulations? Will economic benefits of AI be strong enough to incentivize regulatory reforms? Will AI disempower labor in a way that upends the political voice of the masses?”

Bottom line from this back and forth: To grow explosively, we need either faster automation or total automation. Faster automation means moving retrained workers from old tasks to new ones quickly. Total automation means machines can do everything, including innovation tasks (“Everything from developing new scientific theories and conducting experiments to figuring out how to manufacture and distribute new inventions,” Clancy writes.) Then, economic growth feeds technological discovery in a virtuous loop. This is different from the past, where automation was gradual and humans were still needed at all stages of the discover-invention-innovation process. If AI keeps taking over tasks slowly, we will have steady growth, not explosive growth.

The good news, from my perspective, is that nothing I have argued for in the newsletter assumes explosive growth or the Technological Singularity. Nor did, for that matter, any of the futurist optimism of the immediate postwar “golden age” decades. All those forecasts about undersea cities, space colonies, nuclear-powered, and an America much richer than today assumed faster growth but not fantastical growth, perhaps 3 percent annual per capita GDP growth versus the historical average of 2 percent. Of course, hitting that historical average will require much faster productivity growth since demographics constrain rapid labor force growth (though more immigration would be a big help to both.)

And just in time, here comes AI. Let me point to a new piece in The New York Times, “As Businesses Clamor for Workplace A.I., Tech Companies Rush to Provide It,” reporter by Yiwen Lu:

Earlier this year, Mark Austin, the vice president of data science at AT&T, noticed that some of the company’s developers had started using the ChatGPT chatbot at work. When the developers got stuck, they asked ChatGPT to explain, fix or hone their code. It seemed to be a game-changer, Mr. Austin said. But since ChatGPT is a publicly available tool, he wondered if it was secure for businesses to use.

So in January, AT&T tried a product from Microsoft called Azure OpenAI Services that lets businesses build their own A.I.-powered chatbots. AT&T used it to create a proprietary A.I. assistant, Ask AT&T, which helps its developers automate their coding process. AT&T’s customer service representatives also began using the chatbot to help summarize their calls, among other tasks.

“Once they realize what it can do, they love it,” Mr. Austin said. Forms that once took hours to complete needed only two minutes with Ask AT&T so employees could focus on more complicated tasks, he said, and developers who used the chatbot increased their productivity by 20 to 50 percent.

More of that, please! Faster, please!

5QQ

💡 5 Quick Questions for … policy writer Aaron Renn on what we can learn from Indianapolis

Aaron Renn is a writer and consultant in Indianapolis who is a co-founder and Senior Fellow at American Reformer. He recently wrote a fantastic, thought-provoking chapter on Indianapolis in The Future of Cities. The Midwestern city makes for an interesting case study in the kind of questions Faster, Please! readers might have on their minds. Check out the Q&A below for Aaron’s thoughts on local philanthropy, revitalizing “left-behind” areas, and more.

1/ You write that Indianapolis has benefited from a partnership between the public sector and philanthropists, yet it seems that private philanthropy sometimes fuels spending cuts and ends up substituting and crowding out government money. Is that a bad thing, or should we welcome charity dollars that allow government to shrink its footprint?

Philanthropy has played an increasing civic role in Rust Belt cities as a result of general decline. For example, wealthy residents of Kalamazoo created an endowment specifically to fund city services in that fiscally distressed city. The Cleveland Foundation has become a major player in economic development there. Even in New York, philanthropy played a big role in restoring Central Park during years when the city was struggling.

NYC’s conservancy model is arguably a positive in getting crown jewel type assets off the city’s ledger so that municipal funds can be prioritized for less affluent neighborhoods, but in general I reject the idea of using philanthropy to deliberately shrink government. In part this is because of the opportunity cost. There are some things only the civic sector can do. When it gets refocused on government responsibilities, those other areas suffer. Philanthropy and private sector social entrepreneurship are at their best when dealing with difficult human problems, or supporting transformational initiatives in areas that extend beyond the legitimate scope of government. When it starts substituting or over functioning for government, philanthropy loses effectiveness and can even inhibit addressing civic challenges by allowing politicians to kick the can down the road. To have a high functioning public-private-philanthropic partnership requires that all three sectors be bringing their “A” game to the table.

When philanthropy plays too big a role, that’s generally an indicator of problems elsewhere. In those cases, philanthropy filling the gap may be a necessity. But it’s also a bearish indicator for the community.

It's also a bad idea to overly rely on philanthropy because of the lack of feedback mechanisms. Unlike governments, which periodically have to go before the voters, there’s no external check or feedback loop philanthropy. And there’s almost no public debate or negative feedback to major philanthropies at the local level; everybody sucks up to people that give away money.

2/ How do we better balance and harmonize public sector provision and private philanthropic efforts?

These groups need to know their lane. Government, businesses, universities, wealthy individuals, foundations, and civic groups each have their own core competency. While they can and should collaborate on certain civic initiatives, particularly ones that are intended to be transformational in nature, they should not attempt to substitute for each other to any great extent.

3/ Some economists and policymakers have suggested using federal dollars to plant small technology hubs in faltering geographies like the Rust Belt. Is this a good approach to revitalizing "left behind" areas?

That’s a complex subject I can’t do justice to here. I do think there could be a legitimate federal role in some cases, particularly related to defense type technology. Purdue University in Indiana is a leading aerospace research institution, for example, long linked to the space program and today doing work on items like hypersonics. It would make sense from a pure national security point of view to invest federal money at a place Purdue and presumably elsewhere.

Attracting talent is speculative and strongly influenced by factors largely outside of a city’s control, like climate.

4/ Population growth in cities like Indianapolis is largely driven by people moving in from rural parts of the state. Is there a way small cities should be attracting talent from other states?

Attracting talent is speculative and strongly influenced by factors largely outside of a city’s control, like climate. For example, virtually no metro area in the entire 23-state area I call the “Old North” has attracted a lot of talent from out of state. Instead, I advocate a citizen-centric approach that focuses on the residents a city already has. Invest in your people, improve quality of place, and service the cultural aspirations of your people. If other people are attracted by that, so much the better.

5/ You note that in Indianapolis public-private-philanthropic consensus is hard to achieve but resilient to public opposition. Should this serve as a model to overcome the citizen "vetocracy" problem in other cities?

The Indianapolis system developed organically and is strongly linked to the local culture. Civic culture in Indianapolis has been strongly biased against public conflict for many decades. For example, Notre Dame professor Richard Pierce wrote a book about the history of black political engagement in Indianapolis whose very title of Polite Protest speaks to this culture. I don’t think the Indianapolis model is easily replicable.

Bonus: You have argued that red states should "reorient their philosophy of governance away from a business-centric strategy toward a citizen-centric one." What do you mean by that?

Red state governments frequently enact policies that they argue will attract business, whether that be tax cuts, right to work, incentive programs, regulatory rollbacks, or other. We often hear about Texas or other such places pursuing those policies that have boomed. But again, there is a strong geographic overlay. These success stories are almost exclusively in the Sunbelt. When a red state like Indiana pulled all of these levers, it basically didn’t work. It does better on some measures and worse on others, but Indiana is broadly in the middle of the pack of my 23-state Old North area and is certainly not seeing a Texas, Florida, or Tennessee type boom.

While the business climate is important, I argue that red states should spend more time thinking about the well-being and preferences of the people who live there. Too often, they choose to side with exploitative businesses like slumlords, casinos, etc. instead of their own citizens. Their leaders also frequently embrace leftist policies like DEI in the name of attracting business. It hasn’t worked, and it only angered a citizenry whose cultural aspirations have been neglected or even suppressed.

Micro Reads

▶ Toyota says solid-state battery breakthrough can halve cost and size - Kana Ignaki, FT |

▶ Explainer: Between hope and hype for Toyota’s ‘solid-state’ EV batteries - Peter Campbell and Kana Inagaki, FT |

▶ Eric Schmidt: This is how AI will transform the way science gets done - Eric Schmidt, MIT Tech Review |

▶ Why Immigration Is an Urban Phenomenon - Joan Monras, SF Fed |

▶ Remote Work, Foreign Residents, and the Future of Global Cities - Joao Guerreiro, Sergio Rebelo, and Pedro Teles, NBER |

▶ Shipping Needs Nuclear Power to Solve Its Emissions Problem - David Fickling, Bloomberg Opinion |

▶ AI Could Change How Blind People See the World - Khari Johnson, Wired |

▶ In the Age of A.I., Tech’s Little Guys Need Big Friends - Cade Metz, NYT |

▶ Panic about overhyped AI risk could lead to the wrong kind of regulation - Divyansh Kaushik and Matt Korda, Vox |

▶ How human translators are coping with competition from powerful AI - Timothy B. Lee, Understanding AI |

▶ The Homework Apocalypse - Ethan Mollick One Useful Thing |