⤵ Why populist economics is bad: industrial policy edition

Government interventions should only be done according to strict criteria. That's not how it works currently.

In my essay yesterday, “Why populist economics is bad: trade protectionism edition,” I dug into a new study that documents why recent US protectionist policies have failed to deliver on their promises. Short story: Manufacturing jobs haven't rebounded, trade deficits persist, and economic decoupling from China remains elusive. This result is unsurprising. Protectionism ignores the real drivers of economic change: technological progress and market dynamics.

Again, my baseline view: We should embrace open trade and Hayekian principles of decentralized innovation. Free markets foster the networks and connections that drive growth, allowing for specialization and increased productivity. Yes, trade may disrupt some sectors … even as it creates opportunities elsewhere, leading to net job gains and improved living standards.

While the focus of my previous essay was on the trade policy aspects of “Protectionism is Failing and Wrongheaded: An Evaluation of the Post-2017 Shift toward Trade Wars and Industrial Policy” by my AEI colleague Michael Strain, today I want to talk about the sort of targeted economic intervention exemplified by the Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, both passed in 2022.

Evaluating industrial policies past

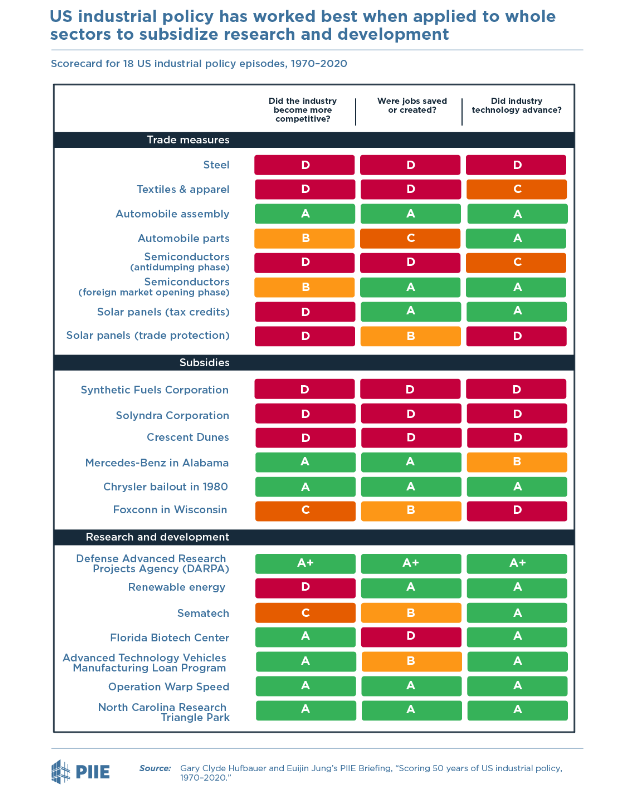

Strain's core critique of industrial policies like the chips part of the Chips Act and clean energy subsidies of the IRA is that they're costly gambles with murky goals and questionable benefits. These well-intended policies distort markets, risk mission creep, and provoke international backlash. While acknowledging some strategic rationales, Strain doubts these clumsy tools will pass a reasonable cost-benefit test. Strain: "Industrial policy works better in theory than in practice. It often fails because real-world factors, limits on state capacity, and competing political objectives often prove to be insurmountable obstacles."

Strain's industrial policy playbook for judging such intervention: Smart initiatives will have clear, achievable goals that don't get tangled in partisan politics. The ideal policy leverages existing US capabilities, demonstrates a positive cost-benefit ratio, and remains insulated from short-term political whims. A few past examples that meet — and fail — these criteria:

Operation Warp Speed: It had a clearly defined goal (developing COVID-19 vaccines rapidly) and leveraged existing US pharmaceutical capabilities. Strain: "The GDP gains from faster vaccine development were an order of magnitude larger than the cost of the program."

DARPA: It remains insulated from partisan politics and is staffed by managers with scientific training. Strain observes: "DARPA-funded projects have contributed to the creation and development of weather satellites, global satellite navigation, the computer mouse, explosive metal forming, the internet, semiconductor chips."

Smoot-Hawley tariffs: It failed to meet its objective of raising agricultural prices and led to retaliation. Strain adds that it "led to a large reduction in exports, which hurt export-intensive businesses.”

Obama's tire tariffs: These had a poor cost-benefit ratio. Strain points out: "This initiative protected a maximum of 1,200 jobs at a cost to American consumers (in the form of higher prices) of $1.1 billion."

Sizing up the Chips Act & IRA

Now let’s shift to present policy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.