Why building hyperloops is hard; AI as a super RA; how bubbles drive tech progress; curing disease by curing aging, and more ...

Quote of the Issue: “To paraphrase John Greenleaf Whittier: We are the people who have thrown the windows of our souls wide open to the sun. We will follow as we can where our hearts have long since gone, and progress will be ours for all mankind to share. Americans have shown the world that we not only dream great dreams, we dare to live those great dreams.” - President Reagan, at a White House luncheon honoring the astronauts of the Space Shuttle Columbia on May 19, 1981.

Ignition

⭐ In a short, sharp essay last year, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen lamented “our widespread inability to build.” The PPE shortage in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic was the immediate catalyst for the piece. But Andreessen broadened the critique to include America’s chronic inability to build (a) housing in high-productivity cities, (b) more spectacular cities, (c) greater capacity at elite universities, and (d) highly automated superfactories to boost domestic manufacturing. Andreessen: “Where are the supersonic aircraft? Where are the millions of delivery drones? Where are the high speed trains, the soaring monorails, the hyperloops, and yes, the flying cars?”

Texans these days are asking the more mundane question, “Why can’t we keep the lights on?” after widespread power failures during a severe cold snap. Indeed, the new annual U.S. infrastructure report card from the American Society of Civil Engineers gives the national electric grid a C- grade (the same as its overall score). Both items will likely be touted when the Biden administration pushes its big infrastructure spending bill later this year.

A previous paucity of spending isn’t the only issue, however. There’s the deeper question of why working with atoms in America is so difficult. Why is it hard to build? Why is it so expensive, complicated, and time-consuming?

Some answers can be found in a paper that was published around the same time as Andreessen’s essay, “Infrastructure Costs” by George Washington University economist Leah Brooks and by Yale law professor Zachary Liscow. The researchers found that starting in the early 1970s, real spending per mile on Interstate construction increased more than three-fold from the 1960s to the 1980s.

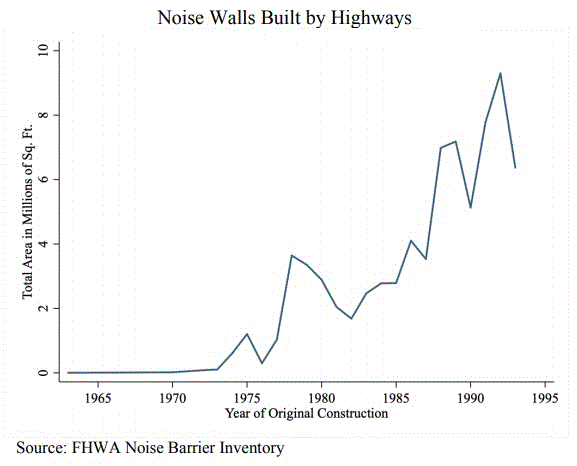

One explanation, according to Brooks and Liscow, is pure Econ 101 stuff. When people get richer, they like nicer and fancier things. It’s true of healthcare, and it’s true of highways. For example: Noise wall construction also started going up around the same time.

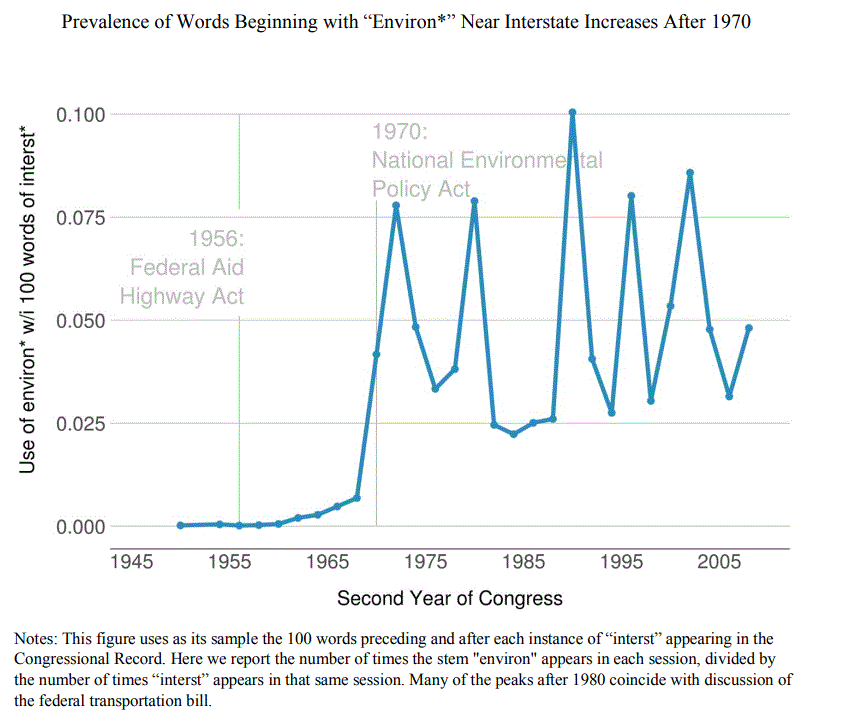

One reason for more noise wall construction — other than people near them pushed for peace and quiet — was that the noise issue played into more general environmental concerns that were also on the rise. And that links into the second explanation from Brooks and Liscow: the rise of “citizen voice.” Here’s how Brooks explained this to me in a recent podcast chat:

I think a great example of this is the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) passed in 1969. I hesitate to talk about this because I don’t intend to demonize environmental regulations — which I think in many cases serve a valuable purpose and force the government to take into account worthy costs — but it’s a very easy example to understand. The day after NEPA passed in 1969, the Environmental Law Institute was founded. The whole purpose of the Environmental Law Institute was to sue under the cause of action that’s granted by the passage of NEPA. And NEPA is just one example of the many statutes passed in that era that gave citizens the ability to sue whenever they thought that the government wasn’t faithfully following the statutory requirements.

There were also judicial decisions at the same time that my co-author can speak to better than I can. But they, again, basically allowed citizens to sue if they thought that the executive agency wasn’t faithfully following the statute as Congress intended. Based on some limited evidence, what we think happened is that the government had to change its spending behavior in a way to satisfy those citizens who are able to make noise. … So what the regulation really allows for is lawsuits, or the threat thereof. Just the threat of a lawsuit could make you write a more careful environmental plan, hold more public hearings, raise the costs of hearings, take into account concerns so as to avoid lawsuits, or hire environmental consultants. This is basically an entire industry that didn’t exist before the 1970s.

And it wasn’t just NEPA. Brooks and Liscow also point to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the 1973 Endangered Species Act that limits development near protected habitat, and the 1972 Clean Water Act that protects wetlands. Reforms proposed by the Trump administration last year might make NEPA less of an obstacle to building, say, an enhanced energy infrastructure — as well as all those things Andreessen mentions. Bad news: The Biden administration might reverse them. Hey, not everything that happened the past four years was a bad thing. In this case, finally correcting an overcorrection from five decades ago seems called for.

Stages

1/ 💻 The exhaustive 2021 Artificial Intelligence Index Report, just published, asked AI experts to identify what they view as last year’s most significant technical breakthroughs. The two easy winners the AlphaFold (DeepMind) predictive model for protein structures and the GPT-3 (OpenAI), a generative text model. I find the former advance particularly exciting. First, there’s the coolness or wow factor of solving a decades-old problem that will help us better understand the foundations of life. Then there are the potential future impacts on drug discovery, curing disease, and “engineering de-novo proteins for industrial tasks.” The role of AI as a research assistant, in health as well as other areas such as materials science, should not be underestimated. The report goes on to note that drug design and discovery received the greatest amount of private AI investment in 2020, nearly $14 billion, 4.5 times higher than in 2019.

2/ 💵 While Faster, Please! mostly focuses on long-term economic growth and technological progress, it’s hard to ignore the boomy times we are entering as the economy reopens and Washington keeps flooding it with cash. If you plug in the $1.9 trillion Biden stimulus, which passed the Senate on Saturday, into the Fed’s macro model, that baby really jumps. Goldman Sachs says such a simulation (also including the upcoming infrastructure bill) “implies 7% Q4/Q4 GDP growth in 2021, a decline in the unemployment rate to 3.7% in 2021Q4 and 3% by 2023Q4, a pickup in core inflation to 2.2% by 2023, and one to two rate hikes in 2023 under our interpretation of the Fed’s new framework.”

The February job report out on Friday might have given a taste of things to come. It showed surprisingly strong employment gains of 379,000 net new jobs, double expectations. And that was with some pretty bad weather last month. JPMorgan economist Michael Feroli told clients it was “a pretty good report, and we expect even better numbers in coming months as the incredibly powerful tailwind of reopening should support some rather large job growth figures.”

And this just now (Sunday evening) from economist Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics:

The economy is off and running. Growth will be rip-roaring during the coming year, with real GDP expected to rise nearly 7% and payrolls by well over 6 million jobs. The winding down COVID-19 pandemic will power this growth—we expect herd immunity no later than July Fourth—massive fiscal support totaling $2 trillion this year, and the unleashing of pent-up demand by higher-income households that socked away cash while sheltering in place. If everything sticks roughly to script, the economy will fully recover from the pandemic, with a sub-4% unemployment rate, two years from now, in early 2023. It will have taken three years for the economy to return to full employment. For context, it took nearly a decade for the economy to find its way back after the financial crisis, and approximately five years after the 1990 and 2000 recessions. The risks to this optimism also appear increasingly two-sided: Much could go wrong if the vaccines fall short of quelling the fast-evolving virus. On the other hand, things could turn out it even better than anticipated if other countries can ramp up their vaccination programs.

3/ 📈 Financial bubbles and speculation aren’t all bad. In the past they’ve helped generate some amazing bursts of innovation, as documented by economist Carlota Perez in her book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Technological revolutions and financial cycles are symbiotic as frenzy leads to funding and diffusion, as well as needed infrastructure. Interviewed recently by the Financial Times, the newspaper characterizes her current view as “we were about halfway through our latest technological revolution, moving from a phase of narrow installation of new technologies such as artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, 3D printing and vertical farms to one of mass deployment.”

No mention here of the space economy, though regular FT readers might note that two space-related businesses, Rocket Lab and Spire, have entered the market via SPACs, investment vehicles that some say are in a bubble ready to burst. Maybe those SPAC bears are correct. But they might do a lot of good in the meantime. As the FT puts it in a separate piece: “Space companies are a moonshot borne aloft by the rocket fuel of cheap money. That momentum trade has more to recommend than some others, such as fledgling electric vehicle companies. Both Rocket Lab and Spire have proven technologies to accomplish highly demanding tasks. This really is rocket science. But like space exploration itself, these investments are only for the brave.”

4/ 🚀 The quote that leads this issue suggests an idealized America — an America of explorers, an America of pioneers and risk takers, an America eager to see what’s over the next hill. But it was Cold War geopolitics, not the spirit of discovery, that drove America to win the Space Race. And when that race was done, so was America’s interest in space as an important national effort. Sure, the public did get excited about the Space Shuttle, its enthusiasm seemed more about national pride than anticipation over how the expensive “space truck” could bring about a space economy.

So here we are, quite distant from the space-faring civilization envisioned by Apollo-era futurists. But that same geopolitical calculus is one reason why I think the resurgent American effort in space will prove enduring. At least in this one instance, China is a stand-in for the old Soviet Union. (And, of course, it isn’t just China. Many nations have ambitions in space, unlike a half century ago.) Superpower competition could energize pro-progress efforts in the United States across a number of fronts as policymakers keep seeing headlines like this one: “In battle with U.S., China to focus on 7 ‘frontier’ technologies from chips to brain-computer fusion.” One concern of mine, however, is that the lesson Washington will draw from China’s efforts and success so far is to go all-in on a China-lite prescriptive industrial policy rather than focusing on and strengthening American core competencies in entrepreneurship and basic research driven by the immigration of global talent.

5/ 🧬 When tech-optimist conversation turns to speculation about “curing aging,” some on the political right balk. Putting the scientific challenge aside for a moment, the whole notion strikes them as transhumanist hugger-mugger where a confident belief in an approaching age of immortality-bestowing super-science has become a religion. But there’s a big difference between living forever and simply living longer and healthier. That’s how “curing aging” is effectively framed in this analysis by venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz from late last year.

The study of aging itself is a tantalizing and magical one—conjuring images of a fountain of youth. … But in a way, the study of aging is a trojan horse, gaining us access to a much more concrete, immediate new world of possibility. Our next, best set of targets for the therapeutics of the future will come from aging biology—therapeutics for diseases that have a massive unmet need, and that many of us are suffering from right now. … Even with our best efforts, best technologies, and best science for each of these major diseases, curing age related diseases one at a time is ultimately low impact. Let’s say we completely cured cancer; that would add a paltry 4 yrs to average lifespan, because another major killer like stroke would be just around the corner. Only by targeting aging itself can we make significant impact on improving quality of life and healthspan.

6/ 🔥 When Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates’ clean energy fund made its first investments back in 2018, one of the companies that got a check was Fervo Energy. Fervo is aiming to use fracking techniques to tap geothermal energy potential of some 100GW in the U.S., according to the company. As MIT Technology Reviews described the effort back then: “If Fervo Energy’s technologies work as intended, they could enable existing geothermal sites to boost electricity production, or allow entirely new areas to tap into heat within the earth’s crust. Increasing geothermal generation could ease the broader shift to cleaner energy systems, because it can provide always-on power or ramp-up as needed, unlike variable wind and solar farms.” If you’re still interested, I recommend checking out this tweetstorm from CEO Tim Latimer about how drill-bit innovation (!) is transforming the sector.

7/ 🌐 Let’s jump back to that Artificial Intelligence Index Report for a moment. Another great nugget is how (a) the percentage of international students among new AI PhD graduates in North America continued to rise in 2019, to 64.3% — a 4.3 percentage point increase from 2018 and (b) how among foreign AI PhD graduates in 2019 in the United States, 81.8% stayed in the US for work. Something for Washington to think about as it alters Trump-era immigration policy. Not only is foreign talent critical to the US AI sector (as I suggest above), but when students to do come here to study, they stay here — at least for now. We shouldn’t take that tremendous asset for granted.

Next Steps

A new poll result reveals sharp pessimism on America’s political right | Washington Post

U.S. National Science Foundation could get $600 million in pandemic relief bill | Science

Betting on death of petrol cars, Volvo to go all electric by 2030 | Reuters

U.S. is ‘not prepared to defend or compete in the A.I. era’ | CNBC