🏫 Why isn't the big plunge in student test scores a national emergency?

Getting kids more schooling is an imperative. So long, three-month summer vaycays. Thanks, school closures!

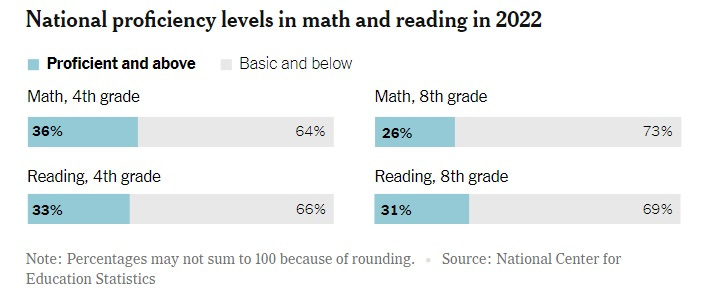

Item: U.S. students in most states and across almost all demographic groups have experienced troubling setbacks in both math and reading, according to an authoritative national exam released on Monday, offering the most definitive indictment yet of the pandemic’s impact on millions of schoolchildren. In math, the results were especially devastating, representing the steepest declines ever recorded on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the nation’s report card, which tests a broad sampling of fourth and eighth graders and dates to the early 1990s. - The New York Times, 10/24/2022

Item: National test results released on Thursday showed in stark terms the pandemic’s devastating effects on American schoolchildren, with the performance of 9-year-olds in math and reading dropping to the levels from two decades ago. This year, for the first time since the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests began tracking student achievement in the 1970s, 9-year-olds lost ground in math, and scores in reading fell by the largest margin in more than 30 years. - The New York Times, 09/01/2022

Well, what did we all think would happen, folks?

Back in the summer of 2020, I wrote that “keeping kids out of school this year would be ... an economic catastrophe, every bit as serious as the deep recession from which we are currently recovering.” Now, more than two years later, I humbly concede my mistake. Yes, the Great Economic Lockdown that year was incredibly damaging, technically the worst recession on record. But the US economy has since recovered all of the job losses suffered during the pandemic. And the economy is now running above its long-term GDP potential (contributing to hot inflation).

So it’s obvious to me, then, that closing schools and shifting to distance learning was a far worse economic catastrophe than the recession. Not that this should be a shocking finding. One of the strongest and most persistent findings of modern economics is that schooling really does something important to help kids become high-functioning adults, including as workers in an advanced, globalized economy.

Those findings are seen to be as true today as when they were first identified in the 1950s. A 2018 literature review by the World Bank found “that the private average global rate of return to one extra year of schooling is about 9 percent a year and very stable over decades.”

Sorry, school skeptics, school is not just daycare for younger students so more of us can go to work. Nor is it just some diabolical capitalist “credentialing” mechanism for older students that allows future employers to find the best workers.

But speaking of capitalism: Back in 2020, my AEI colleague and economist Michael Strain calculated that keeping kids home for another semester after the spring shutdown would represent a loss of over $30,000 per decade in future earnings for a typical worker who graduated high school but didn’t attend college. And if kids only received online schooling until September 2021, the losses for many would likely be even larger. Bad news: Even by June 2021, only a bit more than half of kids were back in-person full time or had that option.

Also this from another AEI colleague, education expert Rick Hess:

It’s hard to design virtual education well under any circumstances. While it can work for some learners, lots of students (especially young students) need the human dimension of schooling. Many students go to class and learn because they like to see their friends and teacher. And they actually need to know their teacher as something other than an occasional square on a Zoom screen. To ask kids to spend the fall semester or an entire year learning from somebody whom they have never actually met in person is to be profoundly unrealistic about how kids learn and how teachers do their job. … So it’s important for kids to get into school buildings on at least a semi-regular basis.

Distance learning is not the metaverse

What did distance learning look like in practice, on the ground? I would suggest checking out this justifiably passionate tweetstorm (of which I am presenting a portion):

If there was anything crueler than the promise of distance learning for all kids, it was the notion there would be some effort to “catch up” students once they were back in the classroom. Again, here’s Hess earlier this year on such a scenario:

No, it's not going to happen. We have no idea how to catch these kids up. I mean, we've been trying really hard to reform American education, certainly since A Nation At Risk, 39 years ago, and arguably for at least a half-century. Look, it's not like somebody has the right answers, and in some school of education somewhere they've got them locked away in the closet, and now we're finally going to crack them out. The reality is, we don't have any good solutions to help kids catch up.

Tutoring for All? Not really

If we fundamentally knew how to “catch-up” kids, we would already be implementing such solutions for all the kids struggling before the pandemic and the school closures. And those are largely the exact same kids who were hurt most by the closures — kids from poorer areas, kids with less educated parents, kids with lower existing academic achievement, and younger students.

So what is happening right now? Well, not the sort of intensive efforts that might help somewhat. In the NBER working paper “The Consequences of Remote and Hybrid Instruction During the Pandemic,” researchers estimated “that high-poverty districts that went remote in 2020-21 will need to spend nearly all of their federal aid on academic recovery to help students recover from pandemic-related achievement losses.” That paper also predicted only a bit more than a quarter of the nearly $200 billion in federal dough provided to state and local education agencies throughout the pandemic would be spent on “academic recovery,” with the remainder “planned for facilities, technology, staffing, and mental and physical health.”

And that’s exactly what is happening. This from The Economist:

Not many districts have chosen to add hours to the school day or weeks to the school calendar, according to rand’s study. That is a missed opportunity: in many bits of America the school year is short by international standards. Schools are also swiftly discovering that there are not nearly enough temporary tutors and substitute teachers available for cleverer catch-up schemes to work on the scale that is required. … At least some schools have created extra staff-training days without lengthening the school calendar. Their pupils are getting even less class time than usual. … Many districts are spending big dollops of their relief money on infrastructure, with the government’s blessing. That includes new and improved air conditioning; sprightlier classrooms and more computers. These kinds of projects have long been demanded by unions and in most cases will benefit children. But they hardly seem good ways of tackling the emergency at hand.

More computers and a new paint job! Of, course! (Good A/C seems wise, however.) Let me propose a different solution, one hinted at in the above quote: more schooling. Lots more schooling. AEI’s Strain:

It would not be unreasonable to operate schools on Saturdays, at least until math and reading scores return to their pre-pandemic trend. Moreover, the school day should be extended by an hour or two, especially for older students, and the school year should be lengthened as well. … These measures will cost money. But Congress enacted legislation in 2020 and 2021 appropriating nearly $200 billion for the explicit purpose of helping states and localities support student performance during the pandemic. Since much of that money has not been spent, why not use it to provide bonuses to teachers who are willing to work after three o’clock, on Saturdays, and in the month of June to help students make up for lost learning?

Yes, there will be complaints — from the teachers unions, from parents with disrupted summer vacations and long weekend plans, and, of course, from kids. But do we really have a choice? Not if we want to maximize opportunity for all our kids. Look, faster economic productivity and growth are key to raising our living standards and maintaining our geopolitical power and political influence. And it’s likely that no single technological advance or policy implementation is going to accomplish all that by itself. (Not even AI and tax cuts!) It's going to take a lot of smart decisions to make that happen. Doing something big and bold about this educational emergency is one of those things.

Micro Reads

▶ Space-based solar power is getting serious—can it solve Earth’s energy woes? - Daniel Cleary, Science | Major investments are likely far in the future, and myriad questions remain including whether beaming gigawatts of power down to the planet can be done efficiently—and without frying birds, if not people. But the idea is moving from concept papers to an increasing number of tests on the ground and in space. The European Space Agency (ESA)—which sponsored the Munich demo—will next month propose to its member states a program of ground experiments to assess the viability of the scheme. The U.K. government this year offered up to £6 million in grants to test technologies. Chinese, Japanese, South Korean, and U.S. agencies all have small efforts underway. “The tone and tenor of the whole conversation has changed,” says NASA policy analyst Nikolai Joseph, author of an assessment NASA plans to release in the coming weeks. What once seemed impossible, space policy analyst Karen Jones of Aerospace Corporation says, may now be a matter of “pulling it all together and making it work.”

▶ What the Alzheimer’s Drug Breakthrough Means for Other Diseases - Kanoko Matsuyama, Bloomberg | It’s been three decades since scientists hypothesized that Alzheimer’s is caused by a buildup of amyloid beta protein in the brain. But it wasn’t until last month that drugmakers achieved a major breakthrough, with Japan’s Eisai Co. and its US partner Biogen Inc. releasing results from a large-scale trial showing they were able to blunt the disease’s progression. The companies are seeking accelerated US approval for the medication, lecanemab, though questions remain about the extent of the benefits, side effects, and how it would be covered by insurers if approved

▶ The Pandemic Uncovered Ways to Speed Up Science - Saloni Dattani, Wired | Big institutions, such as governments and international organizations, should collect and share data routinely instead of leaving the burden to small research groups. It's a classic example of "economies of scale,” where larger organizations can use their resources to build the tools to measure, share, and maintain data more easily and cheaply, and at a scale that smaller groups are unable to. Doing this would help researchers avoid repeating one another’s limited efforts. It would also have large spillover benefits because routine data can be used by many researchers to see trends, make like-for-like comparisons, and be alerted to new problems. While institutions have the ability to do so, many don't because they are unaware of the benefits or unwilling to create fancy dashboards to present it. But data doesn't need to be made attractive—it just needs to be accurate, representative, standardized, and widely usable.

▶ We need more people to go to college - Catherine Rampell, WaPo Opinion | Beyond the individual benefits that accrue to degree holders, the U.S. economy needs more workers with postsecondary educations. Not any and all educations, of course. Whatever the non-monetary benefits of attending, say, art school, degrees from such programs are not in high demand from employers. On the other hand, a lot of solid middle-class jobs — nurses, teachers, dental hygienists, paralegals, even wind-turbine service technicians — require at least some postsecondary education and training, and they have strong expected employment growth. Many higher-paying jobs in STEM fields typically require a postgraduate degree.

▶ For Disabled Workers, a Tight Labor Market Opens New Doors - Ben Casselman, NYT | Employers, desperate for workers, are reconsidering job requirements, overhauling hiring processes and working with nonprofit groups to recruit candidates they might once have overlooked. At the same time, companies’ newfound openness to remote work has led to opportunities for people whose disabilities make in-person work — and the taxing daily commute it requires — difficult or impossible. As a result, the share of disabled adults who are working has soared in the past two years, far surpassing its prepandemic level and outpacing gains among people without disabilities.

—

Long time fan, first time commenter. I agree with the call to do more to help kids catch up because they’ve clearly fallen behind. But the tests show they’ve fallen behind essentially everywhere, regardless of shutdowns. And the first half of the essay puts all of the blame on shutdowns. It’s not the sort of evidence-based reasoning I’d come to appreciate from you.