😱 Who taught us to fear Dystopia? Who taught us we didn't deserve Utopia?

After 50 years of the Great Stagnation, these remain questions worth answering

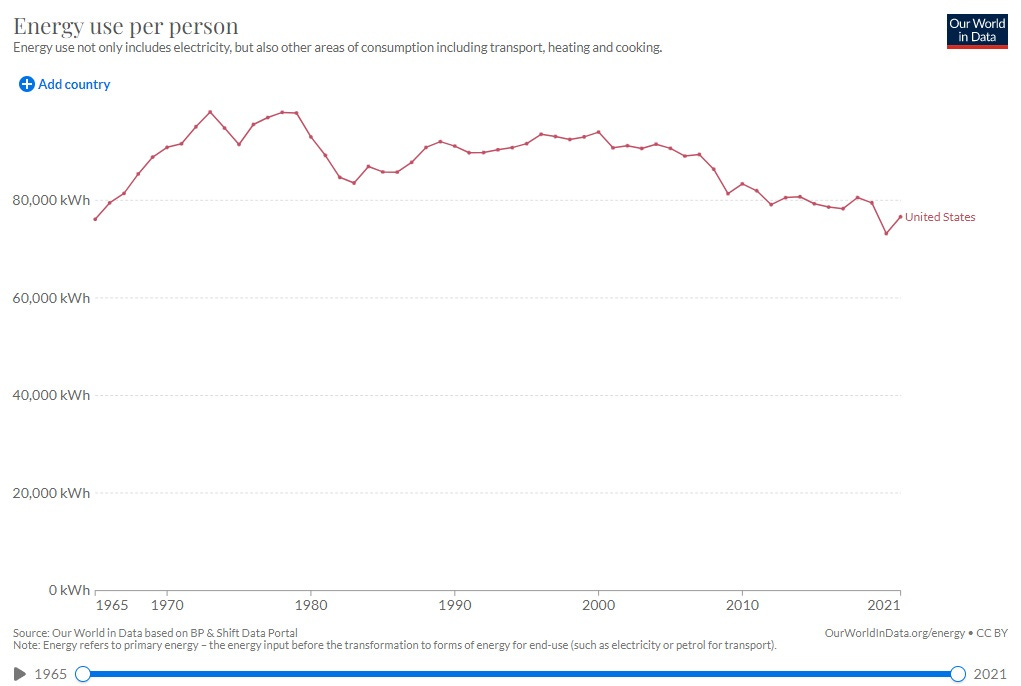

Look, no one is asking for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to explore the roots and ramifications of America’s half-century-long Great Stagnation. But we shouldn’t just breeze over public policy decisions that played a role in that historic and ongoing economic downshift. In a New York Times column over the weekend, “The Dystopia We Fear Is Keeping Us From the Utopia We Deserve,” Ezra Klein continued to elaborate and flesh out his “supply-side progressivism” with a focus on the lack of abundant and carbon-free energy. Good! The vehicle for this exploration is his review of the book “Where Is My Flying Car?” by J. Storrs Hall.

Hall’s big point is that back in the 1970s we became a society in the thrall of “the almost inexplicable belief that there is something wrong with using energy.” We began focusing more on energy efficiency than energy abundance. We thought hard about how to make existing technology use less energy rather than creating new technologies that might require more energy. Hall elaborates on this theory using the notion of flying cars as an example:

There has been considerable advance in aeronautical engineering [over the past decades], but it hasn’t shown up in faster, roomier airliners or flying cars. Most of that considerable effort and ingenuity has gone to energy efficiency. We now have small, sleek private planes that use half the fuel per mile that my old Beechcraft does. What we don’t have, but could have had instead with the same amount of work, would be flying machines that were somewhat less efficient for pure flying because they also were cars. They could also be a lot quieter on takeoff, but known noise reduction techniques, such as slower propellers with more blades, are less energy efficient than current practice. Planes are made lighter by the highest-tech carbon fiber composites, and therefore more fuel-efficient—but also much more expensive.

So what happened? Who’s to blame for our societal energy aversion? Who’s to blame for the Energy Revolution we never had? Why didn’t we continue building nuclear fission reactors, while also funding a Project Apollo for new energy sources such as nuclear fusion? Or more, broadly: Why did we stop dreaming big dreams about what American Civilization could be, here on Earth and beyond. (As conservative futurist Herman Kahn wrote back in 1976, “New and improving technologies aided by today’s fortuitous discoveries [will] further man’s potential for solving current perceived problems and for creating an affluent and exciting world. Man is now entering the most creative and expansive period of history. These trends will soon allow mankind to become the master of the Solar System.”)

Well, you can’t say that Klein is totally uninterested in the answers to those questions. After spending several paragraphs criticizing Hall’s “reactionary futurism” — in Klein’s view, the author is too critical of Washington's “funding and attention" and wrongly characterizes today's environmentalists as anti-progress — the columnist concedes that Hall’s book is worth paying attention to because “the flattening of the energy curve was a moment of civilizational import and one worth revisiting.”

But Klein doesn’t really revisit that moment. To do so honestly, would mean taking a look at the origins of the modern environmental movement and offering some hard criticism of their “achievements.” Sticking with energy: Certainly, by the end of the 1970s, it was obvious to many observers that environmental law was making it hard to develop new energy sources and build new infrastructure. Klein shows little interest in joining an argument that addresses how legitimate environmental concerns quickly became a harmful overcorrection whose impacts we are still dealing with today.

While spending time marveling at possible future advances, — point-to-point rocket travel, desalination, carbon capture, vertical farming, a space elevator — Klein ignores the possibility that we could/should already have those advances and be working on even greater ones. Again, who’s to blame?

I have an idea: Let’s take a look at the role of the New York Times in promulgating a cramped vision of tomorrow, from nuclear energy to regulation to space exploration and exploitation to supersonic airplanes. A few examples:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.