When pokey Americans return to work, will there be jobs waiting?

Also: Why we need an obsession with energy abundance

“It is impossible to make real progress in technology without gambling.” - Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe

In This Issue

The Micro Reads: Solar power from space, creating human eggs, power from supervolcanoes, and more . . .

The Short Read: When pokey Americans return to work, will there be jobs waiting?

The Long Read: Why we need an obsession with energy abundance

The Micro Reads

☀ Space-based Solar Power as a Catalyst for Space Development - Leet W. Wood and Alexander Q. Gilbert | One of the most thorough analyses I’ve seen of this potential technology. From the report: “There are substantial hurdles to operationalizing this concept, especially the high cost of sending the thousands of tonnes of material needed for a gigawatt-class plant into space. However, all the underlying technologies have been demonstrated, and reusable, heavy-lift space systems such as SpaceX's Falcon Heavy and Starship may be poised to lower transport costs significantly.”

🩸 How Silicon Valley hatched a plan to turn blood into human eggs - MIT Technology Review | From the piece:

If scientists can generate supplies of eggs, it would break the rules of reproduction as we know them. Women without ovaries — for example, because of cancer or surgery — might be able to have biologically related children. What’s more, lab-made eggs would cancel the age limits on female fertility, allowing women to have related babies at 50, 60, or even beyond. . . . [And] because the technology could turn eggs into a manufactured resource, it could supercharge the path to designer children. If doctors can make a thousand eggs for a patient, they’ll also be able to fertilize all of them and test to find the best resulting embryos, scoring their genes for future health or intelligence. Such a laboratory process would also permit unfettered genetic editing with DNA engineering tools such as CRISPR. As Conception put it in a pitch sent out earlier this year, the company anticipates that artificial eggs could allow “wide-scale genomic selection and editing in embryos.”

♻ City garbage collection is finally getting the disruption it deserves - Quartz | I’ll be honest, I can’t even believe this is a thing. From the piece: “Trash cans are a ubiquitous, and malodorous, fact of urban life, but a few dozen cities around the world are experimenting with eliminating them. In their place, local governments are installing chutes which connect to an underground system of pneumatic tubes that use high-pressure air to whoosh garbage away to a handful of centralized collection points.”

🌋 Drilling in Yellowstone Could Save America - Jacob R. Borden, WSJ | I’m a geothermal energy fan, but I don’t want people to hear “geothermal” and immediately think of drilling into a supervolcano. That said, Borden points to research from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory that finds “horizontal drilling for geothermal energy extraction . . . [could] siphon off excess energy, producing enough electricity to power as many as 20 million homes for a few thousand years at only 10 cents a kilowatt-hour.” Not to mention, preventing a devastating eruption that could destroy a huge portion of the US and Canada.

💡 To Save the Climate, Give Up the Demand for Constant Electricity - David McDermott Hughes, Boston Review | This sentence from the Rutgers University anthropologist energy rationing advocate will stick with me for some time: “Zimbabwe and Puerto Rico thus provide models for what we might call pause-full electricity.”

The Short Read

👷♂️ When pokey Americans return to work, will there be jobs waiting?

As military strategists put it, “The enemy gets a vote.” Whatever action one side takes, the other will have a response — and probably an unexpected one. That dynamic is one to keep in mind amid talk of a Great Resignation or Great Reassessment among American workers. News stories and social media are filled with anecdotes and posts from workers who don’t want to return to their old gigs or are quitting them, optimistic they can find something better (assuming they want to work at all) or in the case of Baby Boomers, simply retiring.

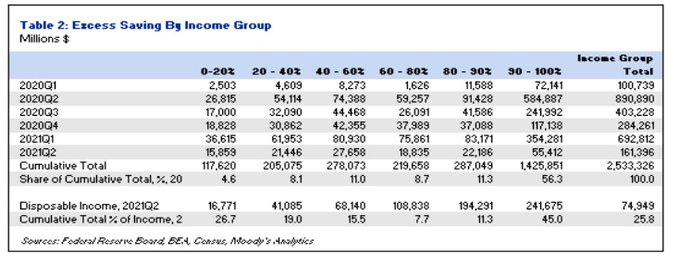

And there’s data to back up those stories. First, the labor force participation rate of prime-age workers, those 25 to 54, is still lower than it was pre-pandemic. Second, 4.3 million workers quit their jobs in August, the highest number on record. Third, households are sitting on nearly $3 trillion of excess savings, giving many unusual flexibility to not work right now. Of course, that savings boom is now fading:

Yet as people rethink their jobs and careers, they need to keep in mind that employers may also be doing much the same. Call it the Great Rethinking by American business. Indeed, that rethinking has been going on throughout the pandemic as strapped businesses are forced to become more efficient or go out of business. And even as the economy has rebounded, many firms aren’t going back to the old ways or assuming a bunch of workers will be soon returning or arriving. Lots of those boomers are probably going to stay retired, and current American politics argues against a near-term rise in immigration. As Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zandi explains (bold by me):

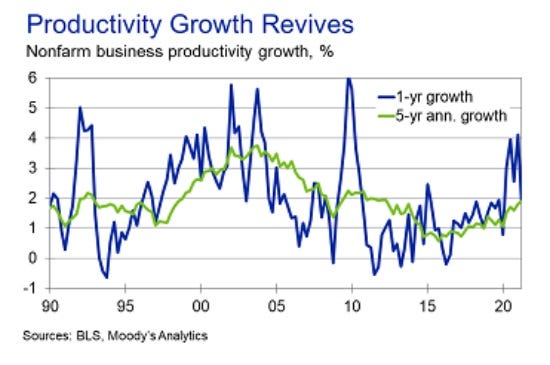

Moreover, while wage growth has held up well during the pandemic and accelerated recently for low-wage workers for which the labor shortages are most problematic, productivity growth has also accelerated. . . . The pick-up in productivity appears due in part to the pandemic itself, as it often takes big changes in the way businesses are organized and operate to take full advantage of the technology and investments they have made. They are reticent to do this when things are going well. Businesses apply the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” philosophy. The pandemic gave many businesses no choice but to make big changes, and it shows in the higher productivity. But the pick-up in productivity growth seems more persistent, as businesses have substantially upped their investment in labor saving technologies.

One can see the jump in productivity in the below chart (though keep in mind these numbers jump around quite a bit from quarter to quarter):

The issue of the economy increasing its productive capacity with fewer workers — Corporate America is reporting strong earnings — was also the subject of a recent podcast chat I had with AEI economist Michael Strain (who also supplied the above job-market numbers):

One of the interesting economic realities right now is the ability of the economy to produce goods and services without all these workers. The level of economic output, GDP, is back to where it would’ve been if there was never a pandemic. Businesses are able to produce goods and services as if there never was a pandemic, even though we’re six or seven million workers in the hole. And my concern is that businesses will have figured out how to get by with fewer workers.

And if there are workers who are lingering on the sidelines — because their unemployment benefits were generous, or because their kid’s school can’t stay open, or because they have so much money in the bank from all the stimulus checks — those workers may be lingering. And by the time they’re ready to come back, labor demand might have cooled off and businesses might say, “Hey, we just need fewer workers than we used to need.” And the jobs that they’re counting on returning to may not be there for all of them.

So time for workers to get off the sidelines — for their good as well as the economy’s. Faster, please!

The Long Read

⚡ Why we need an obsession with energy abundance

Current economic conditions, both here and abroad, teach at least two lessons that are relevant for this newsletter. First, growth is hard, even when government dough is flowing. Last week, the US Commerce Department reported Q3 real GDP growth of 2.0 percent, annualized. That’s less than a third of the pace Wall Street was expecting just a few months ago. JPMorgan economists offered this succinct explanation: “Some slowing from the stimulus-boosted growth of earlier in the year seemed inevitable, but that slowing was exacerbated by supply chain issues as well as a modest headwind from the Delta variant.”

Maybe think of it as a sneak preview of things to come. Even though plenty of economists have conjured super-rosy forecasts for this year and next, they’ve also been predicting a return to the 2 percent-ish, pre-pandemic growth rates in 2023 and beyond. Perhaps even slower given expectations of so-so productivity growth and only slight increases in the labor force.

The other lesson is about energy: It’s a bummer when it gets really expensive and unreliable. As The Economist puts it: “The panic is a reminder that modern life needs abundant energy: without it, bills become unaffordable, homes freeze and businesses stall.” Here in the US, consumers are already experiencing sticker shock at the gas pump with average nationwide prices at their highest level in nearly a decade. Next up: home heating bills, expected to be up 30 percent from last winter, according to the Energy Information Administration.

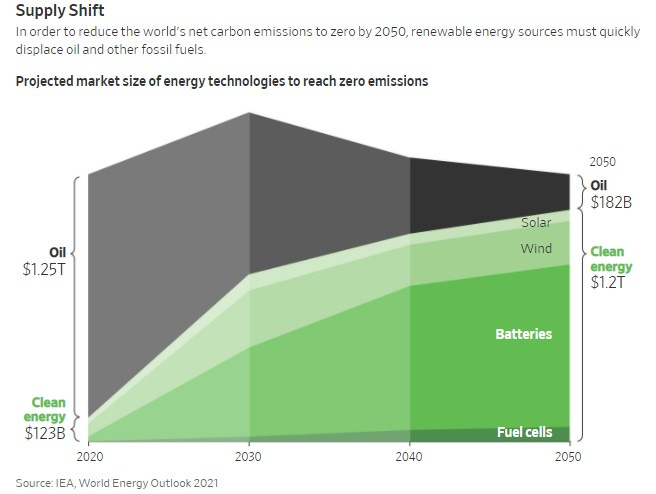

And things are worse elsewhere. From the Wall Street Journal: “Demand for oil, coal and natural gas has skyrocketed world-wide in recent weeks as unusual weather conditions and resurgent economies emerging from the pandemic combine to create energy shortages from China to Brazil to the U.K.” What’s more, this is happening during the so-called Great Transition where countries attempt to pivot from fossil fuels to cleaner sources of energy, as illustrated in this WSJ chart:

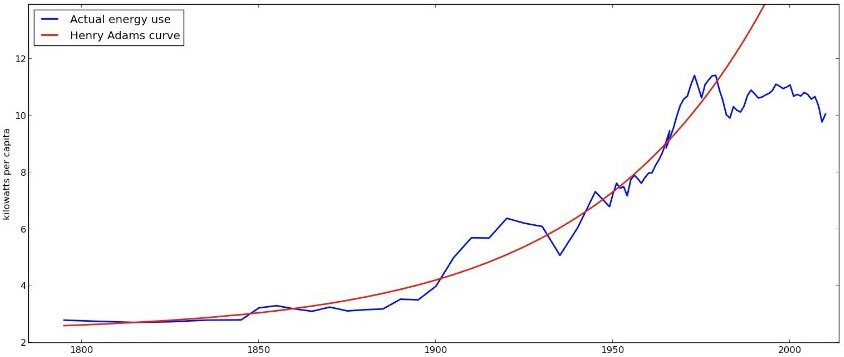

As we make this transition, we must not repeat the mistakes of the past. And one big potential mistake is to ignore the importance abundant energy. That’s one reason why I’ve been writing so much about nuclear fusion and geothermal energy. If you’re interested in accelerating technological progress, then you might already be familiar with this chart:

The image comes from the book Where Is My Flying Car?: A Memoir of Future Past, by scientist J. Storrs Hall and inspired something the historian and member of the famous American policy family wrote about coal and energy more than a century ago. The blue line is actual energy use and the red line is the smoother version illustrating a steady trend of 7 percent a year. From the book:

In the 1970s, the centuries-long growth trend in energy (the “Henry Adams curve”) flatlined. Most of the techno-predictions from 50s and 60s SF had assumed, at least implicitly, that it would continue. The failed predictions strongly correlate to dependence on plentiful energy. American investment and innovation in transportation languished; no new developments of comparable impact have succeeded highways and airliners. . . . If our pre-1970 energy use trend had continued, we’d now use ~30 times as much energy per person, mostly via nuclear power. Which is enough energy for cheap small flying cars.

Now, it’s good to be wary of monocausal explanations for complex phenomena, and I would include the downshift in US productivity growth in that category. But I will concede this explanation probably does have at least some explanatory power. And I’m hardly alone. Economist John Cochrane: “Nuclear does not seem like a promising avenue for powering small aircraft! But the larger point — nuclear power could easily have allowed our society to continue to use more power, without cost or carbon emissions, is surely true.” And economist Robin Hanson: “With nuclear power, we’d have had far more space activity by now. Without it, most innovation in energy intensive things has gone into energy efficiency, and into smaller ecological footprints. Which has cut growth and prevented many things.”

It’s also worth noting the work of Nobel laureate William Nordhaus, whose 2004 paper “Retrospective on the 1970s Productivity Slowdown” focuses on the impact of the 1970s energy shocks:

The slowdown was primarily centered in those sectors that were most energy-intensive, were hardest hit by the energy shocks of the 1970s, and therefore had large output declines. In a sense, the energy shocks were the earthquake, and the industries with the largest slowdown were near the epicenter of the tectonic shifts in the economy. . . . But past is not prologue, and the 1970s productivity slowdown has over the last decade been overcome by a productivity growth rebound originating primarily in the new economy sectors as the economy made the transition from the oil age to the electronic age, the aftershocks of the energy crises have died off and productivity growth has returned to a rate close to its historic norm.

In a bit of bad timing, that paper was written just as the late 1990s-early 2000s productivity boom was coming to an end. And that downshift has continued through the present, though we’ll see how the post-pandemic economy shakes out. I would also point to this 2013 take from the CBO: from the dramatic rise in energy prices after 1973 fails to account for the lack of a similarly strong slowdown in other countries or for the failure of TFP growth to recover after energy prices declined in the 1980s.”

Of course, by the 1980s, it may have been too late. Nuclear was moribund, and more broadly, the notions that (a) energy was a scarce resource, and (b) using too much energy was bad for the planet, were deeply enmeshed in our cultural fabric. And there is evidence that costly energy does affect innovation. Summing up work by John Hassler, Per Krusell, and Conny Olovsson of the Institute for International Economic Studies in Stockholm, The Economist explains that when “energy is abundant, [firms] focus on capital- or labour-saving innovation. When energy is scarce, by contrast, firms do more to improve the energy-efficiency of production, and innovation suffers—as it did in the 1970s.”

And as easy as it is to see how an overweighting of energy efficiency could play a role in the past slowdown of progress, it’s equally easy to see how such a focus could play a role in the future. Indeed, Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon makes this very point in his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, identifying effort to deal with climate change as an anti-growth headwind:

Future carbon taxes and direct regulatory interventions such as the CAFÉ fuel economy standards will divert investment into research whose sole purpose is improving energy efficiency and fuel economy. Regulations that require the replacement of machinery or consumer appliances with new versions that are more energy-efficient but operationally equivalent impose a capital cost burden. Such investments do not contribute to economic growth in the same sense as such early twentieth-century innovations as the replacement of the icebox by the electric refrigerator or the replacement of the horse by the automobile.

When one starts to think about clean energy abundance, it can be hard to think about anything else — as this query suggests:

Among the many answers on the more practical end: carbon capture, desalination, vertical farming. And then a bit further out there: asteroid mining, irrigating the Sahara, mass migration offworld, megastructures. This response is typical:

But maybe the one idea I like the best: “Everyone globally gets to live like 20th century Americans.” Anyway, let’s make sure efforts at efficiency do not again crowd out efforts at creating clean, abundant sources of energy that will fuel an expanding economy, both here and globally.