What went wrong in 1973? (And what didn’t go wrong?)

Also: Let’s not scare people by comparing AI to a god

“Optimism, pessimism, f*ck that — we’re going to make it happen.” - Elon Musk

In This Issue

The Micro Reads: COVID-19 therapeutic, autonomous ships, industrial policy, and more . . .

Best of the Political Economy Podcast: Talking with Brad Stone, author of Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire

The Short Read: Let’s not scare people by comparing AI to a god

The Long Read: What went wrong in 1973? (And what didn’t go wrong?)

The Micro Reads

💊 “Merck Pill Intended to Be Covid-19’s Tamiflu Succeeds in Key Study” - WSJ | Sounds like a game changer. From the piece: “The pill cut the risk of hospitalization or death in study subjects with mild to moderate Covid-19 by about 50%, the companies said Friday. . . . Merck said it expects to produce 10 million courses of treatment by the end of the year, with more doses coming next year. If authorized, Merck would begin shipping doses fairly quickly, [Chief Executive Rob] Davis said.”

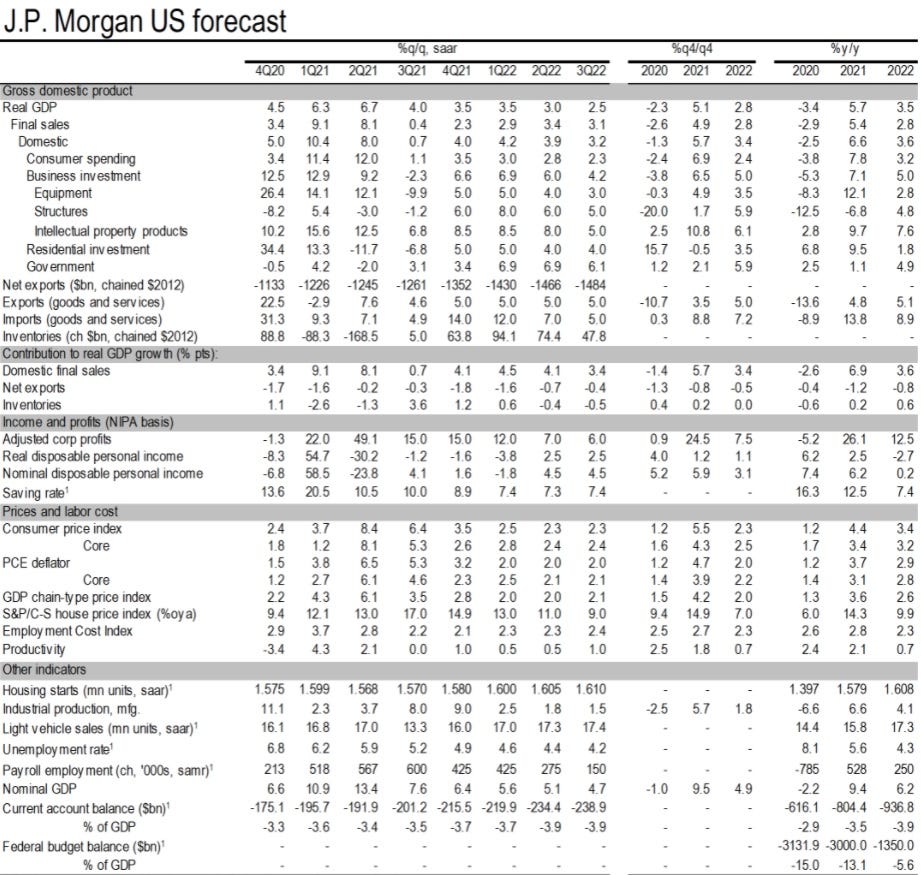

📉 “Another downward revision to Q3 GDP growth” - Michael Feroli, JPMorgan | This is hardly the only Wall Street bank citing the Delta variant and supply-chain issues as undermining their extremely rosy forecasts from earlier this year. From the report: “We are lowering our estimate of Q3 annualized real GDP growth from 5.0% to 4.0% (updated forecast table below). . . . After double-digit growth in the first half of the year, real consumption growth looks like it only inched forward at about a 1% pace last quarter. Supply chain issues continue to crimp real consumer outlays for motor vehicles, which declined over 18% in the three months ending in August (September sales reported later today). Meanwhile Delta fears likely contributed to the recent slowing in real spending for services, which increased only 0.3% in August, the softest gain since last winter.”

🚢 “A Boston company will control a tugboat from 3,600 miles away” - Boston Globe | Sea Machines isn’t looking to remove all crew members from the world’s cargo ships. “Instead the goal is to make shipping safer. According to the German insurance company Allianz, 49 merchant ships sank worldwide in 2020, or roughly four per month.”

🌐 Inside America’s Broken Supply Chain - The Washington Post | When we think “infrastructure,” most of us probably don’t think about America’s ports. But they clearly need an upgrade — both in terms of IT and physical transportation links — even if the first-order reason for our supply-chain troubles is the pandemic.

🌃 “Evidence that overnight fasting could extend healthy lifespan” - Nature | “A feeding schedule of prolonged overnight fasting periods extends healthy lifespan in fruit flies by promoting night-time autophagy, a process in which material in cells is degraded and recycled.”

🏭“Questioning Industrial Policy” - Scott Lincicome and Huan Zhu, Cato Institute | This is a great and underappreciated point: “The American political system is particularly susceptible to public choice problems due to the short duration of many elected federal positions and our well‐developed lobbying and special‐interest group system.”

📱 Tweetstorm of the Issue:

Best of the Political Economy Podcast

In a recent podcast chat with Bloomberg News global technology editor Brad Stone, author of Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire, I asked about the differing space ambitions of Bezos (Blue Origin) and Elon Musk (SpaceX):

Pethokoukis: Musk talks about living on Mars and creating a multi-planetary civilization. Blue Origin’s mission statement is very different. It’s all about Earth, creating a space economy, and lowering our environmental footprint. It seems far more rooted — maybe more customer-centric, if you assume the customer is humanity. Any thoughts on that?

Stone: It’s really funny because in the short term, the companies are direct competitors. Putting aside all the space tourism and suborbital flights we’ve seen over the past couple of weeks, Blue Origin is competing and trying to catch up with SpaceX for contracts to send orbital rockets into space, carry commercial and government satellites, and take astronauts to the space station and then ultimately to the moon. And Blue Origin keeps losing those contracts and then protesting. That’s because New Glenn, their rocket, is years away from fruition, and SpaceX has a complete collection of functioning rockets.

But the long-term goal is different. It’s like we have these different visions attributed to the two CEOs. Musk thinks that to ensure humanity’s survival, we need to be a multi-planetary species. So he wants to go to Mars and set up a colony there. And Bezos simply thinks you might as well go to the North Pole, because it’s going to be much more pleasant than Mars — you can actually breathe the air! So instead, his long-term goal is to have huge space stations orbiting the earth, comprised of material from the moon and harvesting the energy of the sun, and that’s humanity’s future. It’s like we have these two science fiction geeks who read different books and have different visions.

Is Bezos in this for the long run? He may be behind now, but is he going to keep putting resources towards Blue Origin and do what we can, because this is his legacy?

For Bezos, this is his dream. He gave his high school valedictorian speech about opening up the economy in space. This is what he’s going to do. So yes, in his remaining time on this planet, I expect him to be fully into Blue Origin and funding this goal. And look, he basically just put his own life on the line to take the maiden crew voyage of the suborbital rocket, New Shepherd. So I think he’s fully in it.

The Short Read

🤖 Let’s not scare people by comparing AI to a god

Perhaps humanity is on the verge of the Singularity, posthuman emergence, and brilliant machines taking all our jobs. But when I look around, I see Amazon trotting out this cutie, something like a Roomba with an attached iPad:

Now this isn’t to dismiss the sophistication of the Astro. That said, I highlight it to provide a timely example suggesting we’re still a few blocks away from Rosey, the housemaid robot from The Jetsons (arguably the most influential bit of futuristic fiction ever created). Indeed Astro is named after the goofy dog from that cartoon.

Similarly, I might also point to the million self-driving cars that are not on the road right now, despite a 2019 prediction from Elon Musk. And for all the concern about technological unemployment that we heard right before the COVID-19 pandemic — one reason we also started seeing lots of universal basic income proposals — jobless rates back then were at 50-year lows. Finally, US productivity growth has been in a funk since 2005.

America needs faster tech progress and smarter machines (and more of them). So it’s unhelpful when technologists engage in speculation likely to feed into public uneasiness about technology. It’s especially unhelpful when a former executive at Google X, the company’s “moonshot factory,” gives an interview during which he warns that AI researchers are “creating God.” Which is what Mo Gawdat recently did as he promoted his new book Scary Smart: The Future of Artificial Intelligence and How You Can Save Our World.

My concern is that the same disruption-averse impulse that has led to a rise in nativist populism and a backlash against free trade — plus the notion that Silicon Valley is slipping microchips into vaccines — will turn into a broader neo-Luddite impulse. Tax the robots! Remove the kiosks! Ban CRISPR!

There’s nothing wrong with thinking hard about the downside of new technologies, including worker displacement. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. In a recent essay, roboticist Rodney Brooks, a founder of iRobot and creator of the Roomba, notes in a new essay that so far at least, our future god is dependent on its human creators: “Just about every successful deployment of AI has either one of two expedients: It has a person somewhere in the loop, or the cost of failure, should the system blunder, is very low.” Brooks is generally skeptical of the more expansive claims about the future of AI and robotics. And, for now at least, we shouldn’t let wild speculation drive policy.

📉 What went wrong in 1973? (And what didn’t go wrong?)

Get ready for the upcoming golden anniversary of the Golden Age. The immediate postwar decades are often described as a “golden age” for the American economy. If you’re going to assign an end date to that era, 1972 would be a reasonable choice. It was the last full year of strong economic and productivity growth before the nasty 1973–1974 recession. And the subsequent decades have sometimes been called the Great Stagnation or Long Stagnation, meaning a period of historically and surprisingly weak productivity growth — with the exception of the tech-driven productivity boom from 1998–2004.

If you’re looking for a more symbolic event marking the end of that golden age, how about Apollo 17? On December 19, 1972, Eugene Cernan, Harrison Schmitt, and Ronald Evans, splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, just hours after completing the program’s sixth and final manned lunar landing. Neither any American nor any other human has traveled beyond low-Earth orbit since then, much less set foot on the Moon. Also, 1973 saw the premiere of one of the all-time future-pessimist, ecological dystopian films, Soylent Green.

So what happened in 1973 . . . and then 1974, 1975, and beyond? If the question were an orange, it would be the subject of endless intellectual squeezing right to this very day. “Researchers still have not reached consensus on a comprehensive explanation for the slowdown,” the Congressional Budget Office concluded in a 2013 analysis that still holds up. That said, part of the explanation — the subject of Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon’s 2016 book The Rise and Fall of American Growth — seems to be that by the early 1970s, we had exploited all the productivity gains from the big inventions of the past, from internal combustion engine to electrification to the telephone.

Then there’s this: Big game-changing ideas and innovations started getting harder to find, requiring more knowledge and researchers. In their 2017 paper “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” economists Nicholas Bloom, Charles Jones, John Van Reenen note that the that the number of researchers needed to achieve the famous Moore’s Law doubling of computer chip density is more than 18 times larger than the number required in the early 1970s.

Of course, the above analysis has the benefit of a half century of hindsight. What did economists think was happening as the productivity slowdown was still emerging? One fascinating document is a June 1981 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, led at the time by Alice Rivlin, later a director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Clinton and a Federal Reserve governor. “The slowdown appears to be caused by major shifts in relative prices from, for example, oil price

shocks, inflation, and regulation,” concluded the memorandum. But let me dig a bit deeper into the regulation piece of the explanation:

The 1969-1972 period was one of intense regulatory proliferation in the United States, with new legislation concerning air emissions, discharges into waterways, noise pollution, and occupational safety. The industries most severely affected-mining, paper, chemicals, refining, and primary-metals-have suffered the sharpest decelerations in productivity growth since 1973. . . . In mining, for example, productivity declined at an annual average rate of 3.2 percent per year during 1973-1978, after growing at an annual rate of 2.8 percent during 1948-1965 and at 1.6 percent during 1965-1973. Some regulations, especially those concerning air pollution, retard productivity growth through the bias against new sources of pollution. That is, more stringent rules are imposed on new plants or substantial modifications of old ones than on existing facilities. The purpose is to minimize the impact of regulation on existing processes, jobs, and the value of capital. The policy may succeed on this score, but it also provides an incentive for firms to extend the life of older, more technologically-primitive facilities.

This partial diagnosis reminds me a lot of the analysis from the 2019 paper “Infrastructure Costs” by George Washington University economist Leah Brooks and by Yale law professor Zachary Liscow. The researchers found that starting in the early 1970s, real spending per mile on Interstate construction increased more than three-fold from the 1960s to the 1980s. Brooks and Liscow:

First, a raft of legislation in the late 1960s and early 1970s significantly expanded the scope for considering citizen concerns in project design. Perhaps most prominent was the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), enacted in 1970, which requires environmental impact reviews for projects with significant federal funding. Other similar legislation includes the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 that prevents development on national historic sites, the 1973 Endangered Species Act that limits development near protected habitat, and the 1972 Clean Water Act that protects wetlands. In addition to these landmark pieces of legislation, a variety of other federal legislation passed in this era made it more difficult to develop on public lands. By our count, the late 1960s through the mid-1970s saw at least 11 significant federal pieces of legislation that required additional consideration of citizen concerns. In addition, many states also passed their own environmental review statutes. . . . Our findings on costs, while suggestive, are not causal. We also draw no conclusions here as to whether this increased spending increases social welfare.

The oil shocks are long over. Inflation has been quiescent since the early 1980s. What remains is the regulatory overcorrection from the early 1970s. The environmental movement inadvertently helped give us a silent spring for progress just as broader forces were making innovation-driven growth more difficult. That’s not the whole story, but I think it’s one key plotline.

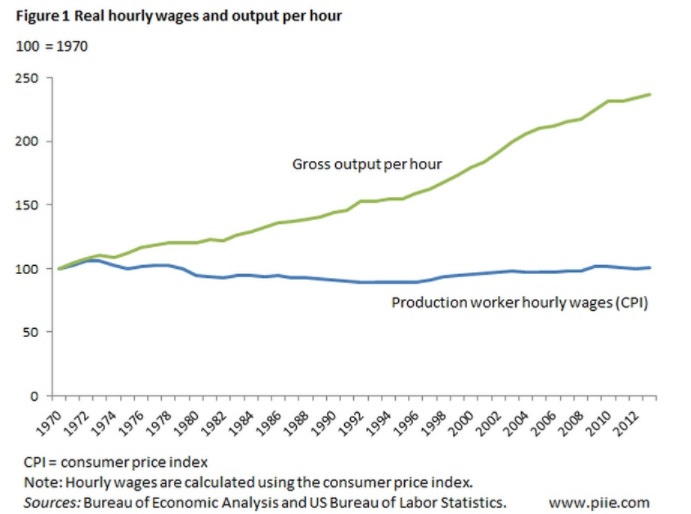

Finally, one thing that probably did not happen in 1973 or thereabouts was that productivity and worker pay become delinked, although you often hear that’s the case. From the Economic Policy Institute: “Since 1973, hourly compensation of the vast majority of American workers has not risen in line with economy-wide productivity.” In fact, you might’ve even seen a chart like this:

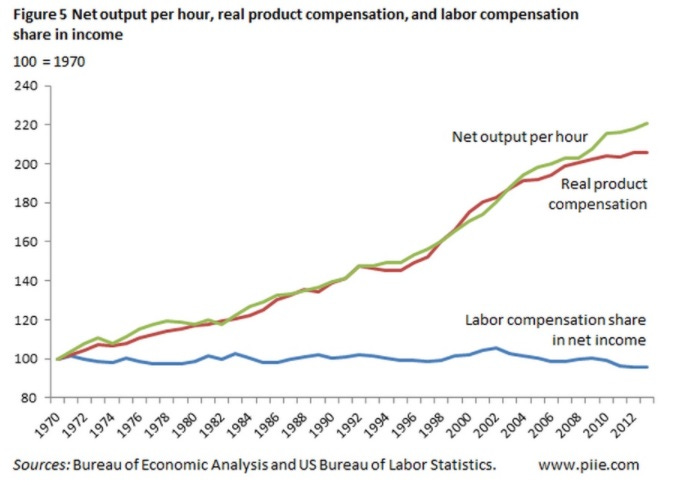

But Robert Lawrence of the Peterson Institute argues this chart better reflects the actual productivity-worker income relationship, properly understood:

According to this chart, wage and productivity growth have pretty much risen together. (And the share of national income going to labor has been steady until recently.) Why the difference between the two charts? Lawrence made several modifications: (a) adjusted for an overly narrow definition of workers; (b) added in benefits to wages, (c) used an inflation measure that better accounts for what workers purchase; and (d) used a more relevant productivity measure. (Also on the pay-productivity subject, I would recommend this paper by my AEI colleague Michael Strain: “The Link Between Wages and Productivity Is Strong.”

While the subject of this newsletter is how to create a better future, it’s important we understand the past — and not to be unduly negative about the present.

Can you explain Cathie Wood's tweet? I don't understand what she means by "quality of earnings". Thanks.